Illuminated Manuscripts in Classical and Mediaeval Times/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV.

Byzantine Manuscripts.

Byzantine style.The history of the origin, development and decay of the Byzantine style in manuscripts, as in other branches of art, is a long and strange one[1]. The origin of the Byzantine style dates from the time when Christianity had become the State religion, and when Constantine transferred the Capital of the World from Rome to Byzantium.

In Russia and other eastern portions of Europe the Byzantine style still exists, though in a sad state of decay, not as an antiquarian revival, but as the latest link in a chain of unbroken tradition, going back without interruption to the age of Constantine, the early part of the fourth century after Christ.

Many strains of influence.During the early years of the Eastern Empire, Constantinople, or "New Rome" as it was commonly called, became the chief world's centre for the practice of all kinds of arts and handicrafts. Owing to its central position, midway between the East and the West, the styles and technique of both met and were fused into a new stylistic development of the most remarkable kind. Western Europe, Asia Minor, Persia and Egypt all contributed elements both of design and of technical skill, which combined to create the new and for a while vigorously flourishing school of Byzantine art. The dull lifeless forms of Roman art in its extreme degradation were again quickened into new life and beauty in the hands of these Byzantine craftsmen, who became as it were the heirs and inheritors of the art and the technique of all the chief countries of antiquity.

Technical skill.In architecture, in mosaic work, in metal work of all kinds, in textile weaving, the craftsmen of New Rome reached the highest level of technical skill and decorative beauty. So also a new and brilliant school of manuscript illumination was soon formed, and Constantinople became for several centuries the chief centre for the production of manuscripts of all kinds.

The Oriental element in Byzantine art shows itself in a love of extreme splendour, the most copious use of gold and silver and of the brightest colours.

Murex purple.Manuscripts written in burnished gold, on vellum stained with the brilliant purple from the murex shell, were largely produced, especially for the private use of the Byzantine Emperors. This murex purple, produced with immense expenditure of labour, came to be considered the special mark of Imperial rank[2]. A golden inkstand containing purple ink was kept by a special official in waiting, and no one but the Emperor himself might, under heavy penalties, use for any purpose the purple ink; and the sumptuous gold and purple manuscripts were for a long time written only for Imperial use.

Gold and purple gospels.The principal class of manuscripts which were written either in part or wholly in this costly fashion were Books of the Gospels; and of these a good many magnificent examples still exist, dating not only from the early Byzantine period, but down to the ninth or tenth century. In these manuscripts the burnished gold and the brilliantly coloured pigments which are used for the illuminations are still as bright and fresh in appearance as ever, but the murex purple with which the vellum leaves were, not painted, but dyed, has usually lost much of its original splendour of colour.

Monotony of style.Before describing the characteristics of Byzantine illuminated manuscripts it may be well to note that the Byzantine style is unique in the artistic history of the world from the manner in which it rapidly was crystallized into rigidly fixed forms, and then continued for century after century with marvellously little modification or development either in colour, drawing or composition.

This absence of any real living development was due to the fact that paintings of all kinds in the Eastern Church, from a colossal mural picture down to a manuscript miniature, were produced by ecclesiastics and for the Church, under a strictly applied series of hieratic rules.

Hieratic rules.The drawing, the pose, the colours of the drapery of every Saint, and the scheme of composition of all sacred figure subjects came gradually to be defined by ecclesiastic rules, which each painter was bound to obey. Thus it happens that during the many centuries which are covered by the Byzantine style of art, though there are periods of decay and revival of artistic skill, yet in style there is the most remarkable monotony. This makes it specially difficult to judge from internal evidence of the date of a Byzantine painting. In manuscripts the palaeographic, not the artistic evidence, is the best guide, aided of course by various small technical peculiarities, and also by the amount of skill and power of drawing which is displayed in the paintings.

Absence of change.Long after the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the Byzantine style of painting survived; and even at the present day the monks of Mt Athos execute large wall paintings, which, as far as their style is concerned, might appear to be the work of many centuries ago. M. Didron found the monastic painters in one of the Mount Athos monasteries using a treatise called the Ἑρμηνεία τῆς ζωγραφικῆς, in which directions are given how every figure and subject is to be treated, and which describes the old traditional forms without any perceptible modification[3]. The proportions of the human form are laid down after the characteristic slender Byzantine models, the complete body, for example, being nine heads in height.

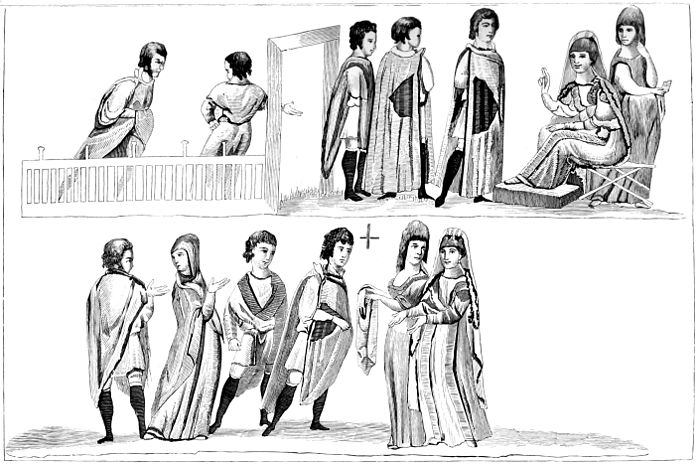

5th century MS. of Genesis.The earliest Byzantine manuscript which is now known to exist is a fragment of the Book of Genesis, now in the Imperial library of Vienna, which dates from the latter part of the fifth century. This fragment consists of twenty-four leaves of purple-dyed vellum, illuminated with miniatures on both sides. In the main the designs are feeble in composition and weak in drawing, belonging rather to the latest decadence of Roman classical art than to the yet undeveloped Byzantine style, which was soon to grow into great artistic spirit and strong decorative power, a completely new birth of aesthetic conceptions, the brilliance of which is the more striking from its following so closely on the degraded, lifeless, worn-out art of the Western Empire. In this manuscript of Genesis there is but little promise of the Renaissance that was so near at hand. Weak drawing.The drawing of each figure, though sometimes graceful in pose, is rather weak, and the painter has hardly aimed at anything like real composition; his figures merely stand in long rows, with little or nothing to group them together. Fig. 6 shows examples of two of the best miniatures, representing the story of the accusation of Joseph by Potiphar's wife. In every way this Genesis manuscript forms a striking contrast to the delicate beauty and strongly decorative feeling which are to be seen in a work of but a few years later, the famous Dioscorides of the Princess Juliana.

The Dioscorides of c. 500 A.D.Among all the existing Byzantine manuscripts perhaps the most important for its remarkable beauty as well as its early date is this Greek codex[4] of Dioscorides' work on Botany, which is now in the Imperial library in Vienna[5], No. 5 in the Catalogue. The date of this manuscript can be fixed to about the year 500 A.D. by the record which it contains of its having been written and illuminated for the Princess Juliana Anicia, the daughter of Flavius Anicius Olybrius who was Emperor for part of the year 472, and his wife Galla Placidia: Juliana Anicia died in 527.

This beautiful manuscript, which was executed in Constantinople, contains five large and elaborate miniatures, and a great number of vignettes representing varieties of plants. The fifth of the large miniatures consists of a central group framed by two squares interlaced within a circle. The plait pattern on the bands which form the framework, and the whole design closely resemble a fine mosaic pavement of the second century A.D. The resemblance is far too close to be accidental; and indeed this manuscript is not the only example we have of miniature painters copying patterns and motives from mosaic floors of earlier date.

Portrait figure.The central group in this beautiful full page painting represents Juliana Anicia, for whom the manuscript was written, enthroned between standing allegorical female figures. Minutely painted figures of Cupids, engaged in a variety of handicrafts and arts, fill up the small spaces in the framework.

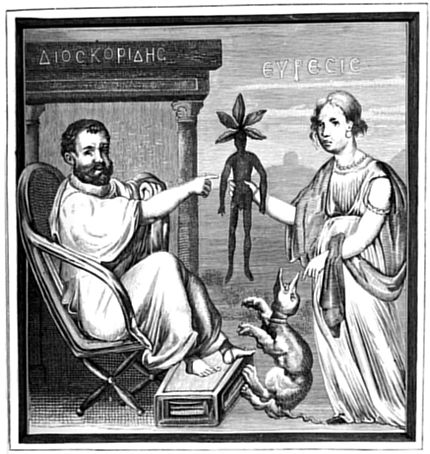

Inferior paintings.In these paintings we have a curious combination of different styles; the enthroned figure of the Princess is of the stiff Byzantine style, while the attendant figures and the little Cupids are almost purely classical in drawing. This manuscript forms a link between the classical or Graeco-Roman and the Christian or Byzantine style. Other paintings in the same manuscript are very inferior in design, partaking of the late Roman decadence, rather than of the better and earlier art of the above mentioned picture. Fig. 7 shows one of these. It represents Dioscorides seated on a sort of throne; in front is a female figure Euresis (Discovery) presenting to him the magic plant mandragora (mandrake). The dying dog refers to the popular belief, given by Josephus, as to the manner in which the mandrake was gathered. When plucked from the ground the mandrake uttered a scream which caused the death of any living creature that heard it; it was therefore usual to tie a dog to the plant and retire to a safe distance before calling it, and so causing the dog to drag the plant out of the ground. On hearing the scream the dog dropped down dead. Cf. Shaks., Romeo and Juliet, IV. iii.

Fig. 7. Miniature from the manuscript of the work on Botany by Dioscorides, executed in Constantinople about 500 A.D.

Colours and gold.The colours used in the Dioscorides of Juliana are very brilliant, especially the gorgeous ultramarine blue, and are glossy in surface owing to the copious use of a gum medium. Gold is very largely and skilfully used, especially to light up and emphasize the chief folds of the drapery, a method which is very widely used in Byzantine art, both in the colossal pictures of the wall-mosaics, and also in most of the finest class of illuminated manuscripts.

Cloisonné enamel.In this use of gold, in thin delicate lines which strengthen the drawing, we have a very distinct copyism of another quite different art, that of the worker in enamelled gold, an art which was practised in Constantinople with wonderful taste and skill. The kind of enamel which was so often imitated by the manuscript illuminator is now called cloisonné enamel from the thin slips of gold or cloisons which separate one colour from another, and mark out the chief lines of the design. So closely did many of the illuminators copy designs in this cloisonné that very often one sees manuscript miniatures which look at first sight as if they were actual pieces of enamel. In other ways too the art of the goldsmith had considerable influence on Byzantine illuminations; and the designs of the mosaic-worker and the miniaturist acted and reacted upon each other, so that we sometimes see an elaborate painting in a book which looks like a design for a wall-mosaic; or again the gorgeous glass mosaics with gold grounds on the vaults and walls of Byzantine churches frequently look like magnified leaves cut out of some gorgeously illuminated manuscript.

The pure Byzantine style.It was only for a short period that manuscripts were executed at Constantinople which, in their miniatures, were links between the classical and the Byzantine style. Thus we find that the famous Greek manuscript of Cosmas Indopleustes in the Vatican library (No. 699) is of the pure and fully developed Byzantine style, with its formal attitudes, its rigid drapery, its lengthy proportions of figure, and stiff monotonous schemes of composition, such as grew to be accepted as the one sacred style, and as such has been preserved by the Eastern Church down to the present century.

This manuscript of Cosmas is certainly a work of Justinian's time, the first half of the sixth century A.D., though it has usually been attributed to the ninth century; it really is but little later than the Dioscorides of Juliana, and yet it has but little trace of the older classical style, either in drawing, composition or colour[6].

The Laurentian library in Florence possesses a manuscript of the Gospels which, though poor as a work of art, has several points of special interest. A contemporary note in the codex records that it was written in the year 586 by the Priest Rabula in the Monastery of St John at Zagba in Mesopotamia.

Early crucifixion.Its illuminations are weak in drawing, coarse in execution and harsh in colouring, but one of them, representing the Crucifixion of our Lord between the two thieves, is noticeable as being the earliest known example of this subject. The primitive Christian Church avoided scenes representing Christ's Death and Passion, preferring to suggest them only by means of types and symbols taken from Old Testament History.

This and other subsequent paintings of the Crucifixion treat the subject in a very conventional way, and it is not till about the thirteenth century that we find the Death of Christ represented with anything like realism.

In the Gospels of the Priest Rabula, Christ is represented crowned with gold, not with thorns; He wears a long tunic of Imperial purple reaching to the feet. The arms are stretched out horizontally, an impossible attitude for a crucified person, and four nails are represented piercing the hands and both feet separately.

Oriental influence.It appears to have been the gloomy Oriental influence that gradually introduced scenes of martyrdom, with horrors of every description into Christian art, which originally had been imbued with a far healthier and more cheerful spirit, a survival from the wholesome classical treatment of death and the grave. Hell with its revolting horrors and hideous demons was an invention of a still later and intellectually more degraded period.

MSS. of the Gospels.Evangeliaria or manuscripts of the Gospels. One of the most important classes of Byzantine manuscripts, and the one of which the most magnificent examples now exist are the Books of the Gospels already mentioned at page 46 as being occasionally, either wholly or in part, written in letters of gold on leaves of purple-dyed vellum.

The four Evangelists.These Imperially magnificent manuscripts are usually decorated with five full page paintings, placed at the beginning of the codex. These five pictures represent the four Evangelists, each enthroned like a Byzantine Emperor under an arched canopy supported on Corinthian columns of marble or porphyry. Each Evangelist sits holding in his hand the manuscript of his Gospel; or, in some cases, he is represented writing it. In the earlier manuscripts, St John is correctly represented as an aged white-bearded man, but in later times St John was always depicted as a beardless youth, even in illuminations which represent him writing his Gospel in the Island of Patmos, as at the beginning of the fifteenth century Books of Hours. Next comes the fifth miniature representing "Christ in Majesty," usually enthroned within an oval or vesica-shaped aureole; He sits on a rainbow, and at His feet is a globe to represent the earth, or in some cases a small figure of Tellus or Atlas with the same symbolical meaning.

The Canons of Eusebius.Other highly decorated pages in these Byzantine Gospels are those which contain the "Canons" of Bishop Eusebius, a set of ten tables giving lists of parallel passages in the four Gospels. These tables are usually framed by columns supporting a semicircular arch, richly decorated with architectural and floral ornaments in gold and colours. Frequently birds, especially doves and peacocks, are introduced in the spandrels over the arches; they are often arranged in pairs drinking out of a central vase or chalice—a motive which occurs very often among the reliefs on the sarcophagi and marble screens of early Byzantine Churches both in Italy and in the East[7]. These birds appear to be purely ornamental, in spite of the many attempts that have been made to discover symbolic meanings in them. Other birds, such as cocks, quails and partridges, are commonly used in these decorative illuminations, Sasanian style.and this class of ornament was probably derived from Persia, under the Sasanian Dynasty, when decorative art and skilful handicrafts flourished to a very remarkable extent[8].

Among the most sumptuous and beautiful illuminations which occur in these Byzantine Gospels are the headings and beginnings of books written in very large golden capitals, so that six or seven letters frequently occupy the whole page. These letters are painted over a richly decorated background covered with floreated ornament, and the whole is framed in an elaborate border, all glowing with the most brilliant colours, and lighted up by burnished gold of the highest decorative beauty[9].

Textus for the High Altar.These sumptuous Evangeliaria, or Textus as they were often called, soon came to be something more than merely a magnificent book. They developed into one of the most important pieces of furniture belonging to the High Altar in all important Cathedral and Abbey churches[10]. Throughout the whole mediaeval period every rich church possessed one of these magnificently written Textus or Books of the Gospels bound in costly covers of gold or silver thickly studded with jewels. This Textus was placed on the High Altar before the celebration of Mass, during which it was used for the reading of the Gospel.

Textus used as a Pax.The jewel-studded covers had on one side a representation of Christ's crucifixion, executed in enamel or else in gold relief, and the book was used to serve the purpose of a Pax, being handed round among the ministers of the Altar for the ceremonial kiss of peace, which in primitive times had been exchanged among the members of the congregation themselves. One of the most magnificent examples of these Textus is the one now in the possession of Lord Ashburnham, the covers of which are among the most important and beautiful examples of the early English goldsmith's and jeweller's art which now exist[11].

The Textus at Durham.An interesting description of the Textus which, till the Reformation, belonged to the High Altar of Durham Cathedral, is given in the Rites and Monuments of Durham written in 1593 by a survivor from the suppressed and plundered Abbey[12], who in his old age wrote down his recollections of the former glories of the Church. He writes, "the Gospeller[13] did carrye a marvelous Faire Booke, which had the Epistles and Gospels in it, and did lay it on the Altar, the which booke had on the outside of the coveringe the picture of our Saviour Christ, all of silver, of goldsmith's worke, all parcell gilt, verye fine to behould; which booke did serve for the Pax in the Masse."

These Textus were not unfrequently written wholly in gold on purple stained vellum, not only during the earliest and best period of Byzantine art but also occasionally by the illuminators of the age of Charles the Great.

Weak drawing of the figure.Returning now to the general question of the style of Byzantine art, it should be observed that, though little knowledge of the human form is shown by the miniaturists, yet they were able to produce highly dignified compositions, very strong in decorative effect. Study of the nude form was strictly prohibited by the Church; and the beauty of the human figure was regarded as a snare and a danger to minds which should be fixed upon the imaginary glories of another world. What grace and dignity there is in Byzantine figure painting depends chiefly on the skilful treatment of the drapery with simple folds modelled in gracefully curving lines.

Livid flesh colour.The utmost splendour of gold and colour is lavished on this drapery, and on the backgrounds, border-frames and other accessories, while the colouring of the flesh, in faces, hands and feet, is commonly unpleasant; with, in many cases, an excessive use of green in the shadows, which gives an unhealthy look to the faces. This copious use of green in flesh tints is especially apparent in the later Byzantine paintings, and again in the Italian imitations of Byzantine art. Even paintings by Cimabue and some of his followers, in the second half of the thirteenth century, are disfigured by the flesh in shadow being largely painted with terra verde[14].

Monastic bigotry.The monastic bigotry, which prohibited study either of the living model or of the beauties of classical sculpture, tended to foster a strongly conventional element in Art, which for certain decorative purposes was of the highest possible value. Anything like realism is quite unsuited both for colossal mural frescoes or mosaics and for miniature paintings in an illuminated manuscript.

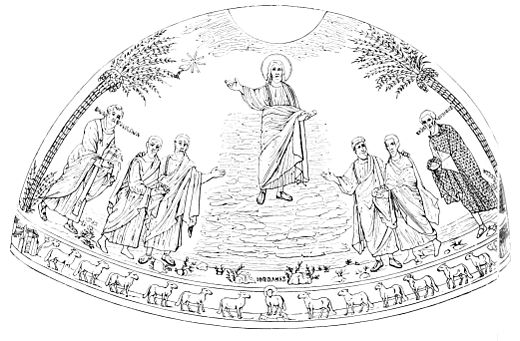

Fine early mosaics.Thus, for example, the existing mosaics on the west front of St Mark's Basilica in Venice[15], which were copied from noble paintings by Titian and Tintoretto, are immeasurably inferior to the earlier mosaics with stiff, hieratic forms designed after Byzantine models, as for example the mosaics in the Apse of SS. Cosmas and Damian in Rome, executed for Pope Felix IV. 526 to 530; see fig. 8.

So, again, the skilfully drawn and modelled figures in a manuscript executed by Giulio Clovio in the sixteenth century are not worthy to be compared, for true decorative beauty and fitness, with the flat, rigid forms, full of dignity and simple, rhythmical beauty which we find in any Byzantine manuscript of a good period[16].

Fig. 8. Mosaic of the sixth century in the apse of the church of SS. Cosmas and Damian in Rome.

Limitations of Byzantine Art.It should, however, be remarked that in Byzantine art this conventional treatment of the human form is carried too far, and therefore, splendid as a fine Byzantine manuscript usually is, it falls far short of the almost perfect beauty that may be seen in Anglo-Norman and French illuminated manuscripts of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, such marvels of beauty, for example, as French manuscripts of the Apocalypse executed in the first half of the fourteenth century in Northern France; see below, page 118.

Edict against statues.Till the eighth century, Byzantine art, both in manuscripts and in other branches of art, continued to advance in technical skill, though little change or development of style took place. In the eighth century the iconoclast schism, fostered by the Emperor Leo III. the Isaurian, an uncultured and ignorant soldier who began by issuing an edict against image-worship in the year 726 A.D., gave a blow to Byzantine art which brought about a very serious decadence during the ninth and tenth centuries, more especially in Constantinople, which up to that time had been one of the chief literary and artistic centres of the Christian world.

Pictures of all kinds, as well as statues, were destroyed by the iconoclast fanatics, and the cause of learning suffered almost as much as did the arts of painting and sculpture.

Frankish MSS.One result of this schismatic outbreak was that Constantinople ceased to be one of the chief centres for the production of beautiful illuminated manuscripts, and various Frankish cities, such as Aix-la-Chapelle and Tours, took its place under the enlightened patronage of Charles the Great the Emperor of the West, who, in the second half of the ninth century, by the aid of the famous Northumbrian scholar and scribe Alcuin of York, brought about a wonderful revival of literature and of the illuminator's art in various cities and monasteries within the Western Empire.

Byzantine decadence.At the end of the eleventh century Byzantine art, practised in its original home, had reached the lowest possible level. Thus, for example, a manuscript of some of the works of St Chrysostom (Paris, Bibl. Nat. Coislin., 79) contains miniatures the figures in which are mere sack-like bundles with little or no suggestion of the human form. The whole skill of the artist has been expended on the painting of the elaborate patterns on the dresses; drawing and composition he has not even attempted.

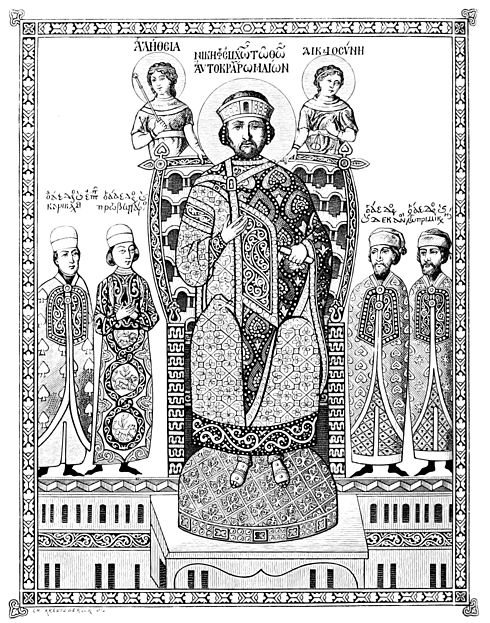

Fig. 9 shows a miniature from this manuscript, representing the Greek Emperor enthroned between four courtiers, and two allegorical figures of Truth and Justice. The Emperor is Nicephoros Botaniates, who reigned from 1078 to 1081. An equally striking example of the degradation of Byzantine art in Germany is illustrated on page 78.

Fig. 9. Miniature from a Byzantine manuscript of the eleventh century; a remarkable example of artistic decadence.

Want of life in Byzantine Art.After this period of decay during the tenth and eleventh centuries, Byzantine art began to revive, largely under the influence of the West; the original life and spirit had, however, passed away, and the subsequent history of Byzantine art is one of dull monotony and growing feebleness, the inevitable result of a continuing copying and recopying of older models.

It is rather as a modifying influence on the art of the West that Byzantine painting continued to possess real importance. As a distinct and isolated school, Constantinople fell into the background at the time of the iconoclasts and never again came to the front as an artistic centre of real importance[17].

- ↑ For a valuable account of Byzantine manuscripts, see Kondakoff, Histoire de l'Art Byzantin, Paris, 1886-1891.

- ↑ The title Porphyro-genitus, "Born in the purple," referred to the fact that Byzantine Empresses brought forth their children in a magnificent room lined with slabs of polished porphyry.

- ↑ A translation of this curious treatise was published by Didron and Durand, in their Manuel d'iconographie chrétienne; Paris, 1845.

- ↑ All manuscripts described in this book, from the Byzantine school onwards, may be understood to be in the codex form and written on vellum, unless they are otherwise described.

- ↑ Published by Lambecius, Comment. sur la Bibl. de Vienne, 1776, Vol. III.

- ↑ Copies of some of the miniatures in the Vatican Cosmas are given by N. Kondakoff, Histoire de l'Art Byzantin, Paris, 1886, Vol. I. pp. 142 to 152.

- ↑ St Mark's in Venice and the churches of Ravenna and Constantinople are full of examples of this design.

- ↑ This Sasanian art was an inheritance from ancient Babylon and Assyria, and was the progenitor of what in later times has been called Arab art, though the quite inartistic Arabs appear to have derived it from the Persians whom they conquered and forcibly converted to the Moslem Faith.

- ↑ The mere gold of even the finest Byzantine manuscripts is never as sumptuous or as highly burnished as that in manuscripts of the fourteenth century, owing to its being usually applied as a fluid pigment, or at least not over the best kind of highly raised ground or mordant, which is described below at p. 234.

- ↑ In early times and indeed throughout the whole mediaeval period very few objects of any kind were placed upon the High Altar even in the most magnificently furnished churches. In addition to the chalice and paten, and the Textus, the only ornaments usually allowed were a small crucifix and two candlesticks. The modern system of crowding the mensa of the altar with many candles and flowers did not come in till after the Reformation. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the Pax was usually a separate thing, of more convenient size and weight than the heavy, gold-covered Textus.

- ↑ Fine coloured plates of this wonderful Textus-cover were published in 1888 by the Society of Antiquaries in their Vetusta Monumenta.

- ↑ Published in 1844 by the Surtees Society of Durham.

- ↑ The "Gospeller" was the officiating Deacon; the Sub-deacon being called the "Epistoller."

- ↑ The remarkable artistic advance which was made by Giotto is to be seen not only in his improved and more realistic drawing, but also in his freedom from the long-established abuse of green in his flesh painting, for which he substituted a warmer and healthier tint.

- ↑ Of the original mosaics on the west façade of Saint Mark's only one remains of the original highly decorative twelfth century mosaics. The rest, shown in Gentile Bellini's picture of Saint Mark's, have all been replaced by later mosaics. Inside the church, happily, the old mosaics still, in most places, exist; see p. 61.

- ↑ See page 202 for an account of Giulio Clovio.

- ↑ Mr M. R. James has pointed out to me an interesting example of similar designs being used by illuminators of manuscripts and by mosaic-workers. The designs of the miniatures in a fifth or sixth century manuscript of Genesis in the British Museum (Otho, B, vi) are in many cases identical with those of the twelfth and thirteenth century mosaics in Saint Mark's at Venice; see Tikkanen, Genesisbilder, Berlin.