Labour and Childhood/The Projection of Hands

CHAPTER IV

THE FIRST TOOLS, OR THE PROJECTION OF HANDS

MOVEMENT, play, art, are all a kind of preparation. They are all, but especially the last two, imitative in character, reflecting impressions received—and they are a preparation; but for what? For something that out-distances them all and is entirely different from every one of them. For toolmaking.

A tool differs entirely from a picture, or statue, or any work of art, because it can be used as a member. It is used at first as a member, and, indeed, the earliest tool makers were not conscious of it as anything outside their own bodies.

The German, Ernest Kapp, was the first to show fully and in detail what the tool is. In his book, Philosophie der Technik (from which some of the following illustrations are taken), he shows how in remote ages man struggling for life with creatures stronger than himself and hardly lifted any higher than they in the scale of consciousness yet began to do what none of them had done. No bird has made a new wing, no wild beast has forged a new tooth or paw. These do not project themselves. But this feeble creature, the ancestor of man, began to project himself, and in doing so climbed, as it were, out of that lower self, reached beyond it, and began to understand it.

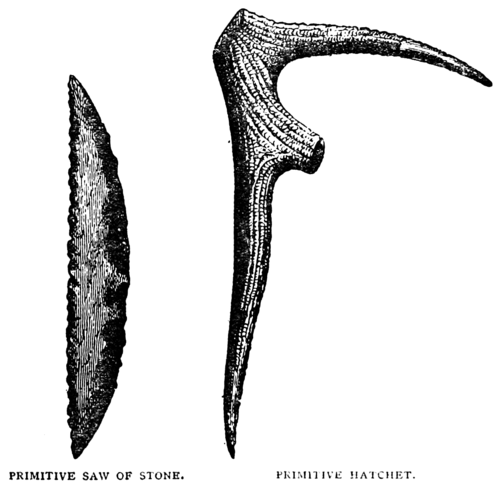

It was certainly not the desire to know himself which induced the ancestor of man to make his first tool.[1] He wanted to strike, to pull, to tear—not to know himself! He stumbled on the new track driven by the primal hungers. His hand was doubtless very unlike the hand of the latter-day man—the fingers more locked or webbed, as they are even to-day in the hands of some children. And for ages the tools he made seem to reflect this hard narrow hand and locked fingers in the heavy stone axe, the stone hatchets and hammers of the stone period. The point, however, is, that he began to project this hand that was not yet a hand.

A very prominent part of it would be the grasping, claw-like finger and finger-nail. These were destined to be projected in a great many positions, and in finest detail. A knife is a broad, sharp nail projected; the saw is a set of nails, or perhaps teeth; and the primitive hatchet was a finger-nail and looks very like a talon, as did its maker's finger. The fist is a hammer. It must have been a narrow, sharp kind of hammer at first, for the power to close the hand depends on the power to open it, and there is good reason to think that the hand opened slowly. Opened it was, however; and the palm projected at last in the plane, and the hollowed palm in the cup and basket. Even the arm was projected at last as a lance, and also as a rudder and oar, which is the simple form of a stretched arm and flat hand. The moving arm is seen to-day in many workshops, on the river sides, and lifting places; and the perfected human arm in beautiful tools. Still the impulse to perfect seems to be, for the most part, unconscious. Here is an early German axe.

In contrast to this heavy tool, that looks like a weapon, there is this drawing from Kapp's book, of the axe of a modern American backwoodsman. The iron blade lies parallel with the shoulder and its powerful muscles, the elbow is parallel with the outward upper curve of the handle. The wrist corresponds to the middle of the inner curve, and the whole axe is, as Kapp has shown, a faithful copy of its original model, and its proportions fulfil the

The meaning of this unconscious selection was not dwelt upon, or even noted perhaps, by Pestalozzi or Froebel, but it is not therefore a thing to be ignored by all who come after them.

- ↑ The "rounding to a separate mind" is a slow process, and is going on to-day slowly, as in bygone ages. But the savage has still a much vaguer idea of his own frame as a separate thing than have civilized people. Mr. Dudley Kidd, in a book called Savage Childhood, tells how little Kaffirs beat the toys of those who have injured them. A grown-up Kaffir who had a headache believed that the pain was in the roof of the hut! And they can hardly locate pain, and are slow to learn what it means to hurt others. Thus the first tool-makers were probably as conscious of their tools as of their hands, and used one simply as a part of the other.