Belfast in 1792 had acquired more than 100 tunes composed by him, and asserted that this was but a small portion of them. In 1809 a sort of commemoration of him was held in Dublin. The late Lady Morgan bequeathed £100 to the Irish sculptor Hogan, for the purpose of executing a bas-relief of the head in marble, which has been placed in St. Patrick's Cathedral. It was copied from a rather youthful and idealized portrait prefixed to 'Hardiman's Irish Minstrelsy.'

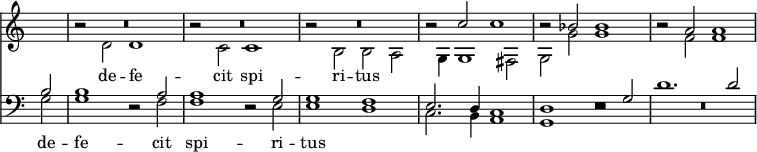

OCHETTO (Lat. Ochetus; Fr. Hoquet; Old Eng. Hocket). A curious device in mediæval Discant, the sole merit of which consisted in interrupting one or more Voice parts—generally including the Tenor—by meaningless rests, so introduced as to produce an effect analogous to that of the hiccough—whence the origin of the word. [See Hocket.] It seems to have made its first appearance in the Sæcular Music of the 13th century; but no long time elapsed before it was introduced into the Discant sung upon Ecclesiastical Plain Chaunt, on which account it was severely condemned in the Decretal issued by Pope John XXII, in 1322. The following specimen is from a Sæcular Song of the 14th century, preserved in MS. at Cambrai, and printed in extenso in Coussemaker's 'Histoire de l'Harmonie au Moyen Age' (Paris, 1852).

etc.

In the latter half of the 14th century the popularity of the Ochetus began rapidly to wane; and in the 15th it was so far forgotten that Joannes Tinctoris does not even think it necessary to mention it in his 'Diffinitorum Terminorum Musicorum.'

But though the Ochetus so soon fell into disrepute as a contrapuntal device, its value, as a means of dramatic expression, has been recognised, by Composers of all ages, with the happiest possible result. An early instance of its appearance, as an aid to expression, will be found in Orazio Vecchi's Motet, 'Velocitur exaudi me' (Venice, 1590), where it is employed, with touching pathos, at the words defecit spiritus meus.

etc. As instances of its power in the hands of our greatest Operatic Composers, we need only mention the death-scenes of Handel's Acis, the Commendatore in 'Don Giovanni,' and Caspar in 'Der Freischütz.'

OCTAVE. An octave is the interval of eight notes, which is the most perfect consonance in music. The ratio of its sounds is 1 : 2; that is, every note has twice the number of vibrations of its corresponding note an octave lower. The sense of identity which appears to us between notes of the same name which are an octave or more apart, arises chiefly from the upper octaves and their harmonics corresponding with the most prominent harmonics of the lower note. Thus Helmholtz says, 'when a higher voice executes the same melody an octave higher, we hear again a part of what we heard before, namely the even-partial tones of the former compound tones, and at the same time we hear nothing that we had not previously heard. Hence the repetition of a melody in the higher octave is a real repetition of what has been previously heard, not of all of it, but of a part. If we allow a low voice to be accompanied by a higher in the octave above it, the only part-music which the Greeks employed, we add nothing new, we merely reinforce the even-partials. In this sense, then, the compound tones of an octave above are really repetitions of the tones of the lower octaves, or at least of part of their constituents.'

Irregularly consecutive octaves are forbidden in music in which the part-writing is clearly defined. The prohibition is commonly explained on the ground that the effect of number in the parts variously moving is pointlessly and inartistically reduced; at the same time that an equally pointless stress is laid upon the progression of the parts which are thus temporarily united either in octaves or unison. Where however there is an appreciable object to be gained by uniting the parts, for this very purpose of throwing a melodic phrase or figure into prominence, such octaves are not forbidden, and small groups or whole masses of voices, or strings, or wind instruments, are commonly so united with admirable effect.

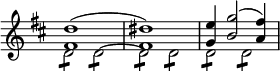

The interval of an augmented octave, exceeding the octave by a semitone, is occasionally met with; as in the following example from the first subject ot the Overture to Don Giovanni:—

etc. It is very dissonant.