Solinus (fl. 3rd century) and jet ornaments are found with Roman relics in Britain. Probably the supply was obtained from the coast of Yorkshire, especially near Whitby, where nodules of jet were formerly picked up on the shore. Caedmon refers to this jet, and at a later date it was used for rosary beads by the monks of Whitby Abbey.

The Whitby jet occurs in irregular masses, often of lenticular shape, embedded in hard shales known as jet-rock. The jet-rock series belongs to that division of the Upper Lias which is termed the zone of Ammonites serpentinus. Microscopic examination of jet occasionally reveals the structure of coniferous wood, which A. C. Seward has shown to be araucarian. Probably masses of wood were brought down by a river, and drifted out to sea, where becoming water-logged they sank, and became gradually buried in a deposit of fine mud, which eventually hardened into shale. Under pressure, perhaps assisted by heat, and with exclusion of air, the wood suffered a peculiar kind of decomposition, probably modified by the presence of salt water, as suggested by Percy E. Spielmann. Scales of fish and other fossils of the jet-rock are frequently impregnated with bituminous products, which may replace the original tissues. Drops of liquid bitumen occur in the cavities of some fossils, whilst inflammable gas is not uncommon in the jet-workings, and petroleum may be detected by its smell. Iron pyrites is often associated with the jet.

Formerly sufficient jet was found in loose pieces on the shore, set free by the disintegration of the cliffs, or washed up from a submarine source. When this supply became insufficient, the rock was attacked by the jet-workers; ultimately the workings took the form of true mines, levels being driven into the shales not only at their outcrop in the cliffs but in some of the inland dales of the Yorkshire moorlands, such as Eskdale. The best jet has a uniform black colour, and is hard, compact and homogeneous in texture, breaking with a conchoidal fracture. It must be tough enough to be readily carved or turned on the lathe, and sufficiently compact in texture to receive a high polish. The final polish was formerly given by means of rouge, which produces a beautiful velvety surface, but rotten-stone and lampblack are often employed instead. The softer kinds, not capable of being freely worked, are known as bastard jet. A soft jet is obtained from the estuarine series of the Lower Oolites of Yorkshire.

Much jet is imported from Spain, but it is generally less hard and lustrous than true Whitby jet. In Spain the chief locality is Villaviciosa, in the province of Asturias. France furnishes jet, especially in the department of the Aude. Much jet, too, occurs in the Lias of Württemberg, and works have been established for its utilization. In the United States jet is known at many localities but is not systematically worked. Pennsylvanian anthracite, however, has been occasionally employed as a substitute. In like manner Scotch cannel coal has been sometimes used at Whitby. Imitations of jet, or substitutes for it, are furnished by vulcanite, glass, black obsidian and black onyx, or stained chalcedony. Jet is sometimes improperly termed black amber, because like amber, though in less degree, it becomes electric by friction.

See P. E. Spielmann, “On the Origin of Jet,” Chemical News (Dec. 14, 1906); C. Fox-Strangways, “The Jurassic Rocks of Britain, Vol. I. Yorkshire,” Mem. Geol. Surv. (1892); J. A. Bower, “Whitby Jet and its Manufacture,” Journ. Soc. Arts (1874, vol. xxii. p. 80).

JETHRO (or Jether, Exod. iv. 18), the priest of Midian, in the Bible, whose daughter Zipporah became the wife of Moses. He is

known as Hobab the son of Reuel the Kenite (Num. x. 29; Judg.

iv. 11 ), and once as Reuel (Exod. ii. 18); and if Zipporah is the wife of Moses referred to in Num. xii. 1, the family could be regarded as Cushite (see Cush). Jethro was the priest of Yahweh, and resided at the sacred mountain where the deity commissioned

Moses to deliver the Israelites from Egypt. Subsequently

Jethro came to Moses (probably at Kadesh), a great sacrificial

feast was held, and the priest instructed Moses in legislative

procedure; Exod. xviii. 27 (see Exodus) and Num. x. 30 imply

that the scene was not Sinai. Jethro was invited to accompany

the people into the promised land, and later, we find his clan

settling in the south of Judah (Judg. i. 16); see Kenites. The

traditions agree in representing the kin of Moses as related to

the mixed tribes of the south of Palestine (see Edom) and in

ascribing to the family an important share in the early development

of the worship of Yahweh. Cheyne suggests that the

names of Hobab and of Jonadab the father of the Rechabites

(q.v.) were originally identical (Ency. Bib. ii. col. 2101).

JETTY. The term jetty, derived from Fr. jetée, and therefore

signifying something “thrown out,” is applied to a variety of

structures employed in river, dock and maritime works, which

are generally carried out in pairs from river banks, or in continuation

of river channels at their outlets into deep water; or out into

docks, and outside their entrances; or for forming basins along

the sea-coast for ports in tideless seas. The forms and construction

of these jetties are as varied as their uses; for though they

invariably extend out into water, and serve either for directing

a current or for accommodating vessels, they are sometimes

formed of high open timber-work, sometimes of low solid projections,

and occasionally only differ from breakwaters in their

object.

Jetties for regulating Rivers.—Formerly jetties of timber-work were very commonly extended out, opposite one another, from each bank of a river, at intervals, to contract a wide channel, and by concentration of the current to produce a deepening of the central channel; or sometimes mounds of rubble stone, stretching down the foreshore from each bank, served the same purpose. As, however, this system occasioned a greater scour between the ends of the jetties than in the intervening channels, and consequently produced an irregular depth, it has to a great extent been superseded by longitudinal training works, or by dipping cross dikes pointing somewhat upstream (see River Engineering).

|

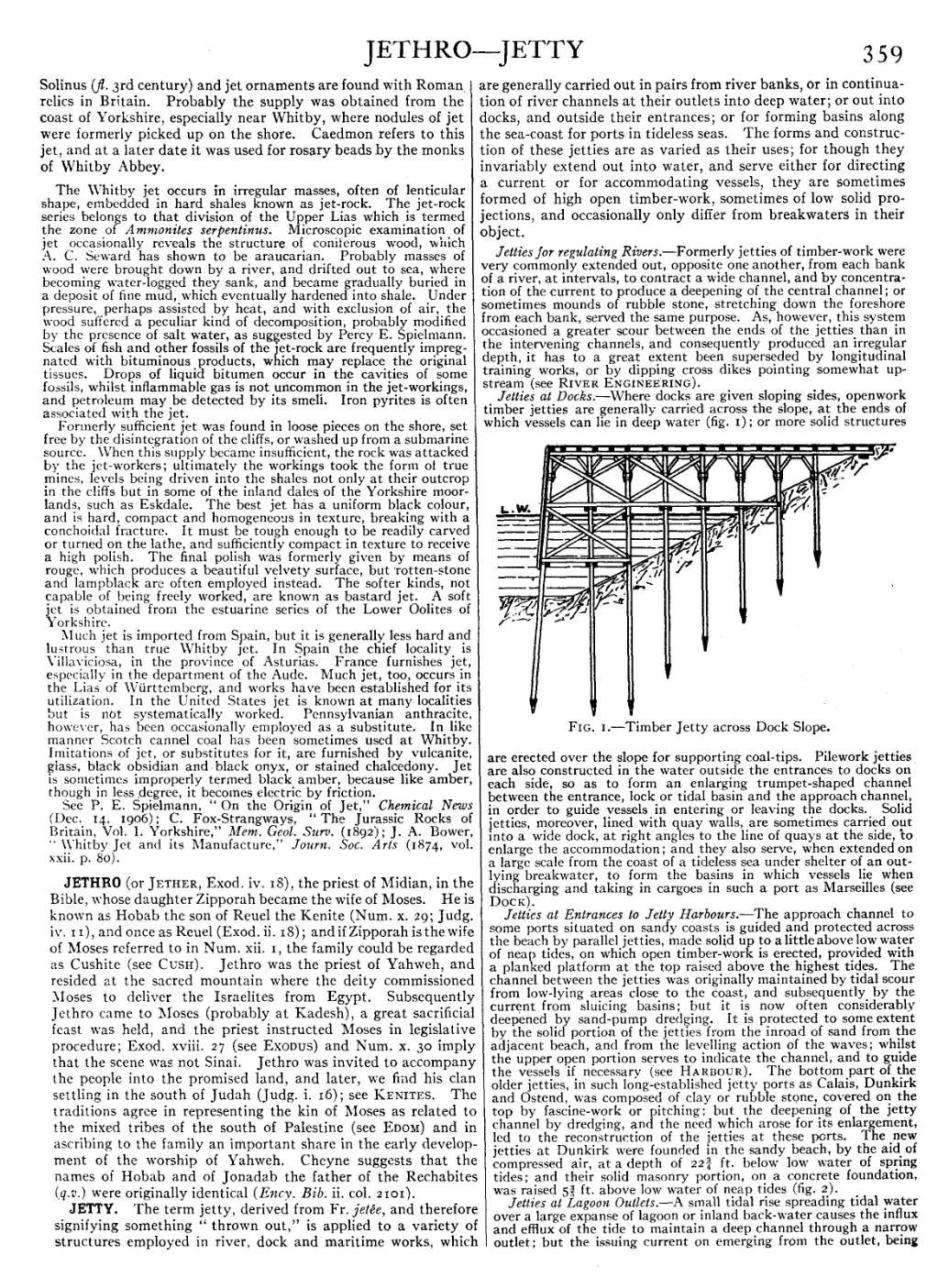

| Fig 1.—Timber Jetty across Dock Slope. |

Jetties at Docks.—Where docks are given sloping sides, openwork timber jetties are generally carried across the slope, at the ends of which vessels can lie in deep water (fig. 1); or more solid structures are erected over the slope for supporting coal-tips. Pilework jetties are also constructed in the water outside the entrances to docks on each side, so as to form an enlarging trumpet-shaped channel between the entrance, lock or tidal basin and the approach channel, in order to guide vessels in entering or leaving the docks. Solid jetties, moreover, lined with quay walls, are sometimes carried out into a wide dock, at right angles to the line of quays at the side, to enlarge the accommodation; and they also serve, when extended on a large scale from the coast of a tideless sea under shelter of an outlying breakwater, to form the basins in which vessels lie when discharging and taking in cargoes in such a port as Marseilles (see Dock).

Jetties at Entrances to Jetty Harbours.—The approach channel to some ports situated on sandy coasts is guided and protected across the beach by parallel jetties, made solid up to a little above low water of neap tides, on which open timber-work is erected, provided with a planked platform at the top raised above the highest tides. The channel between the jetties was originally maintained by tidal scour from low-lying areas close to the coast, and subsequently by the current from sluicing basins; but it is now often considerably deepened by sand-pump dredging. It is protected to some extent by the solid portion of the jetties from the inroad of sand from the adjacent beach, and from the levelling action of the waves; whilst the upper open portion serves to indicate the channel, and to guide the vessels if necessary (see Harbour). The bottom part of the older jetties, in such long-established jetty ports as Calais, Dunkirk and Ostend, was composed of clay or rubble stone, covered on the top by fascine-work or pitching; but the deepening of the jetty channel by dredging, and the need which arose for its enlargement, led to the reconstruction of the jetties at these ports. The new jetties at Dunkirk were founded in the sandy beach, by the aid of compressed air, at a depth of 2234 ft. below low water of spring tides; and their solid masonry portion, on a concrete foundation, was raised 535 ft. above low water of neap tides (fig. 2).

|

| Fig. 2.—Dunkirk East Jetty. |

Jetties at Lagoon Outlets.—A small tidal rise spreading tidal water over a large expanse of lagoon or inland back-water causes the influx and efflux of the tide to maintain a deep channel through a narrow outlet; but the issuing current on emerging from the outlet, being