however, in the allied genus Haliclystus (fig. 1), proving its medusan nature beyond all doubt.

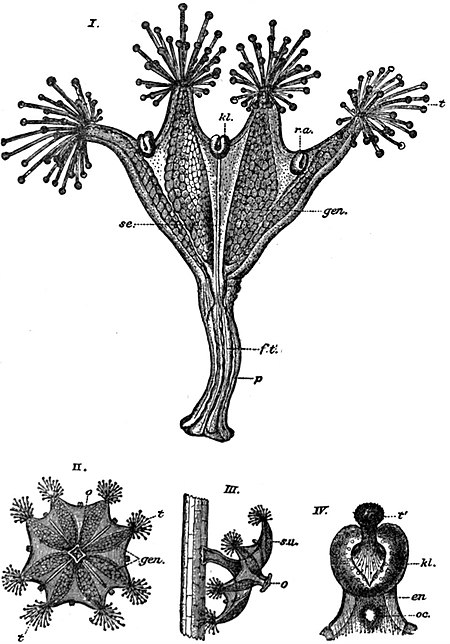

The body-form of the Scyphomedusae varies from that of a conical or roughly cubical cap (fig. 4), to that of a shallow saucer or disk (fig. 2a). The tentacles vary in number from four, the primitive number, to a very large number, but in one suborder, the Rhizostomeae, tentacles are absent altogether (fig. 3, a). Typically the tentacles have the form of long flexible filaments, hollow or solid, implanted singly on the margin of the umbrella (fig. 3, b), but in some species they occur in groups or tufts (fig. 15), and in Lucernaria and its allies a bunch of small capitate tentacles is found on each of the eight adradial lappets of the margin (fig. 1). A true velum is absent, as already stated, but in Charybdaea (fig. 4) a structure is found termed a velarium (Ve), which is a flap hanging down from the margin of the umbrella, and which consists of a fold of the subumbral ectoderm containing endodermal canals. A true velum, such as is found in Hydromedusae, never contains endoderm.

The mouth may be a simple structure at the extremity of the manubrium, or may be four-cornered, with the corners drawn out into so-called oral arms, each of which bears on the inner side a groove continuing the angle of the mouth (fig. 2a). In some genera the oral arms are of great length, and in the suborder Rhizostomeae they undergo concrescence to form a proboscis (fig. 3, a), in such a way that the mouth becomes nearly obliterated, and is reduced to a system of fine canals opening to the exterior by small pores.

The mouth leads into the spacious stomach, which is typically four lobed (fig. 2b, v). On the floor of the stomach are borne the conspicuous gonads (ov), and also tentacle-like processes termed gastric filaments or phacellae, projecting into the cavity of the stomach. The gonads are folds of the endoderm containing generative cells, and are primitively four in number, situated interradially, but each gonad may be divided into two by the partition which separates two adjacent lobes of the stomach, that is to say, by one of the areas of concrescence between exumbral and subumbral endoderm, whence arises a condition with eight gonads which is by no means uncommon. As a rule these medusae are of separate sexes, but hermaphrodite forms are known, for example, the conspicuous British (east-Atlantic) medusa Chrysaora (fig. 3, b).

Immediately below each gonad the subumbral ectoderm is pushed in, as it were, to form a pit or deep cavity (fig. 2a, x, y) opening by a wide aperture (GP). These cavities are known as the infundibular or subgenital cavities. They serve probably for the aeration of the gonads by admitting to their vicinity water with its dissolved oxygen; they never serve as genital ducts, since the generative products are always dehisced into the stomach and pass out by the mouth. In some genera, for instance, Cyanea and its allies the gonad as a whole protrudes through the subgenital cavity as if it had undergone a hernia, and hangs down in the subumbral space as if suspended by a mesentery (fig. 15). Usually the four subgenital cavities are distinct from each other (so-called tetrademnic condition), but in many Rhizostomeae, for example, Crambessa, the subgenital cavities join together under the subumbral floor of the stomach (so-called monodemnic condition) and coalesce to form a so-called subgenital portico placed on the oral side of the stomach, opening by four interradial apertures between the oral arms, that is to say, by the four primitive apertures of the subgenital pits. In Nausithoë subgenital pits are absent altogether, and the same condition may be found in Charybdaeidae.

The gastroyascular system shows every degree of complexity from a very primitive to a highly elaborate type of structure. Taking as a starting-point the wide archenteric cavity which the medusa inherits primitively from the antecedent actinula-stage (see article Medusa), we find, in such a form as Tessera, four interradial areas of concrescence between the exumbral and subumbral layers of endoderm, four so-called septal nodes or “cathammata,” subdividing the stomach into four wide, radially situated pouches which communicate with each other beyond the septal nodes by wide apertures constituting what is termed by courtesy a ring-canal. In other cases the areas of concrescence may extend as far as the margin of the umbrella, so that the lobes of the stomach are completely separated from one