steak may be cut from any meat or fish, but the best-known is a “beef-steak,” cut properly from the rump a “rump-steak,” or part of the loin a “tenderloin.” A “porter-house” steak is a choice cut of steak from the loin, so named apparently first in New York from a well-known “porter-house,” an eating-house where chops, steaks, &c., and porter or stout were served, at which these steaks were a speciality. A steak grilled between two other steaks, which are not served after the cooking is finished, is also sometimes called a “porter-house” steak.

STEAM (O. Eng. steam, vapour, smoke, cf. Du. stoom; the origin

is unknown), water-vapour. Dry steam is steam free from

mechanically mixed water particles; wet steam, on the other

hand, contains water particles in suspension. Saturated steam

is steam in contact with liquid water at a temperature which is

the boiling point of the water and condensing point of the steam ;

superheated steam is steam out of contact with water heated

above this temperature. For theoretical considerations see

Vaporization, and for the most important application see

Steam Engine; also Water.

STEAM ENGINE, 1. A steam engine is a machine for the

conversion of heat into mechanical work, in which the working

substance is water and water vapour. The working substance

may be regarded from two points of view. Thermodynamically

it is the vehicle by which heat is conveyed to and through the

engine from the hot source (the furnace and boiler). Part of

this heat suffers a transformation into work as it passes through,

and the remainder is rejected, still in the form of heat. Mechanically

the working substance is a medium capable of exerting

pressure, which effects this transformation in doing work by

means of the changes of volume which it undergoes in the

operation of the machine. Regarded as a thermodynamic

device, the function of the engine is to get as much work as

possible from a given quantity of heat or, to go a step further

back, from the combustion of a given quantity of fuel. Accordingly,

a question of primary importance is what is called the

efficiency of the engine, which is the ratio of the work done to

the heat supplied. Before, however, proceeding to discuss

the steam engine in this aspect, or treating of the mechanics

of its modern forms, it may be useful to give a brief historical

sketch of its early development as an industrial appliance.

In any such sketch the chief share of attention must necessarily

be given to the work of James Watt. But a process of evolution

had been going on before the time of Watt which prepared the

steam engine for the immense improvements it received at his

hands. His labours stand in natural sequence to those of

Thomas Newcomen, and Newcomen’s to those of Denis Papin

and Thomas Savery. Savery’s engine in its turn was the reduction

to practical form of a contrivance which had long before

been known as a scientific toy. The most modern type of all,

the steam turbine of C. A. Parsons, is a new departure which

has but little to connect it directly with the past; but even the

steam turbine not only profits by the inventions of Watt, but

in its characteristic feature

finds crude prototypes in

apparatus which employed

the kinetic energy of jets of

steam.

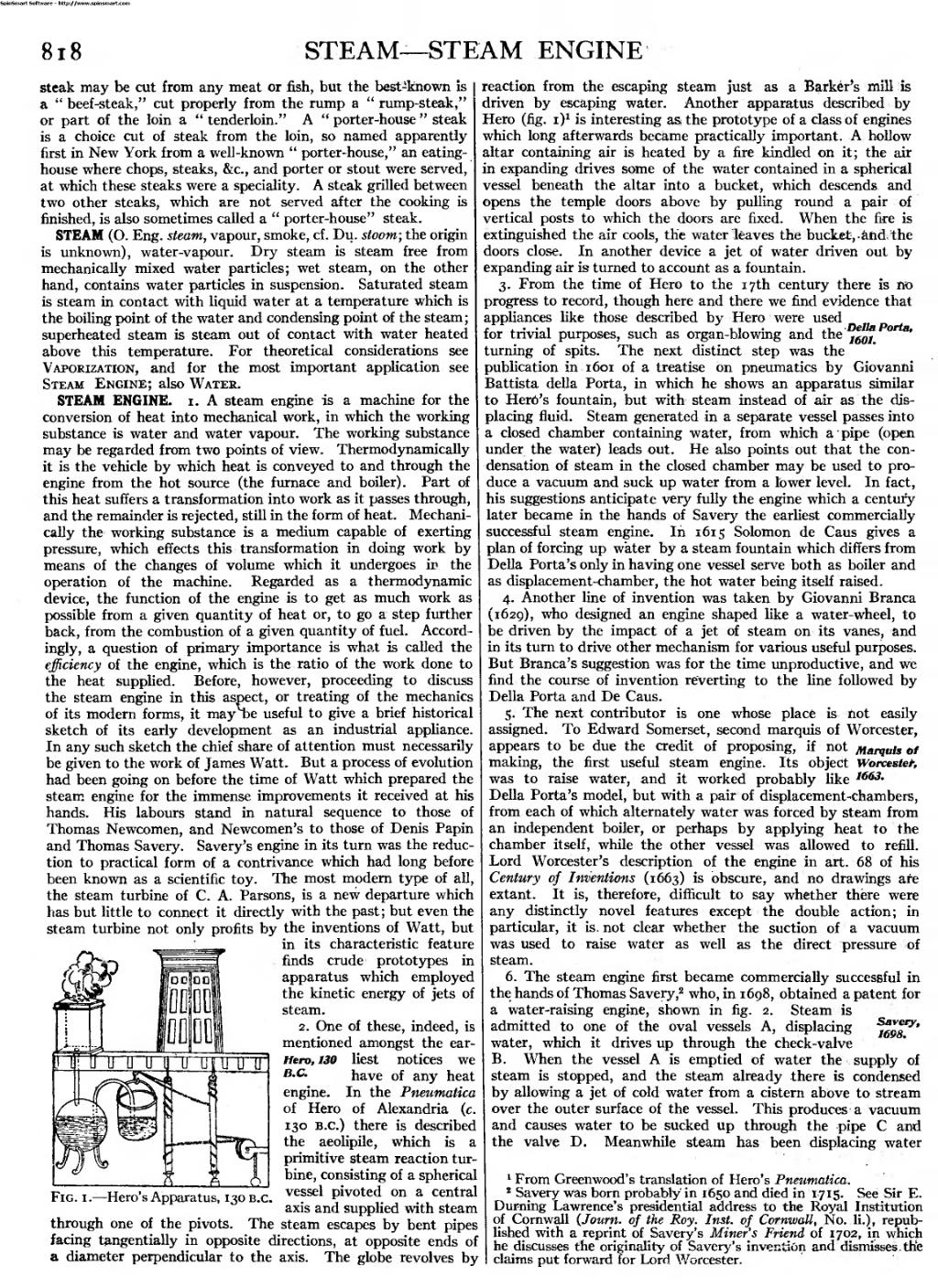

Fig. 1.—Hero’s Apparatus, 130 B.C.

2. One of these, indeed, is

mentioned amongst the earliest

notices we

have of any heat

engine. In the Pneumatica

of Hero of Alexandria (c.

130 B.C.) there is described

the aeolipile, which is a

Hero, 130

B.C. primitive steam reaction turbine,

consisting of a spherical

vessel pivoted on a central

axis and supplied with steam

through one of the pivots. The steam escapes by bent pipes

facing tangentially in opposite directions, at opposite ends of

a diameter perpendicular to the axis. The globe revolves by

reaction from the escaping steam just as a Barker’s mill is

driven by escaping water. Another apparatus described by

Hero (fig. 1)[1] is interesting as the prototype of a class of engines which long afterwards became practically important. A hollow altar containing air is heated by a fire kindled on it; the air in expanding drives some of the water contained in a spherical

vessel beneath the altar into a bucket, which descends and

opens the temple doors above by pulling round a pair of

vertical posts to which the doors are fixed. When the fire is

extinguished the air cools, the water leaves the bucket, and the

doors close. In another device a jet of water driven out by

expanding air is turned to account as a fountain.

3. From the time of Hero to the 17th century there is no progress to record, though here and there we find evidence that appliances like those described by Hero were used for trivial purposes, such as organ-blowing and the Della Porta, 1601 turning of spits. The next distinct step was the publication in 1601 of a treatise on pneumatics by Giovanni Battista della Porta, in which he shows an apparatus similar to Herb’s fountain, but with steam instead of air as the displacing fluid. Steam generated in a separate vessel passes into a closed chamber containing water, from which a pipe (open under the water) leads out. He also points out that the condensation of steam in the closed chamber may be used to produce a vacuum and suck up water from a lower level. In fact, his suggestions anticipate very fully the engine which a century later became in the hands of Savery the earliest commercially successful steam engine. In 1615 Solomon de Caus gives a plan of forcing up water by a steam fountain which differs from Della Porta’s only in having one vessel serve both as boiler and as displacement-chamber, the hot water being itself raised.

4. Another line of invention was taken by Giovanni Branca (1629), who designed an engine shaped like a water-wheel, to be driven by the impact of a jet of steam on its vanes, and in its turn to drive other mechanism for various useful purposes. But Branca’s suggestion was for the time unproductive, and we find the course of invention reverting to the line followed by Della Porta and De Caus.

5. The next contributor is one whose place is not easily assigned. To Edward Somerset, second marquis of Worcester, appears to be due the credit of proposing, if not making, the first useful steam engine. Its object Marquis of Worcester, 1663. was to raise water, and it worked probably like Della Porta’s model, but with a pair of displacement-chambers, from each of which alternately water was forced by steam from an independent boiler, or perhaps by applying heat to the chamber itself, while the other vessel was allowed to refill. Lord Worcester’s description of the engine in art. 68 of his Century of Inventions (1663) is obscure, and no drawings are extant. It is, therefore, difficult to say whether there were any distinctly novel features except the double action; in particular, it is not clear whether the suction of a vacuum was used to raise water as well as the direct pressure of steam.

6. The steam engine first became commercially successful in

the hands of Thomas Savery,[2] who, in 1698, obtained a patent for

a water-raising engine, shown in fig. 2. Steam is

admitted to one of the oval vessels A, displacing

Savery,

1698.

water, which it drives up through the check-valve

B. When the vessel A is emptied of water the supply of

steam is stopped, and the steam already there is condensed

by allowing a jet of cold water from a cistern above to stream

over the outer surface of the vessel. This produces a vacuum

and causes water to be sucked up through the pipe C and

the valve D. Meanwhile steam has been displacing water

- ↑ From Greenwood’s translation of Hero’s Pneumatica.

- ↑ Savery was born probably in 1650 and died in 1715. See Sir E. Durning Lawrence’s presidential address to the Royal Institution of Cornwall (Journ. of the Roy. Inst, of Cornwall, No. li.), republished with a reprint of Savery’s Miner’s Friend of 1702, in which he discusses the originality of Savery’s invention and dismisses the claims put forward for Lord Worcester.