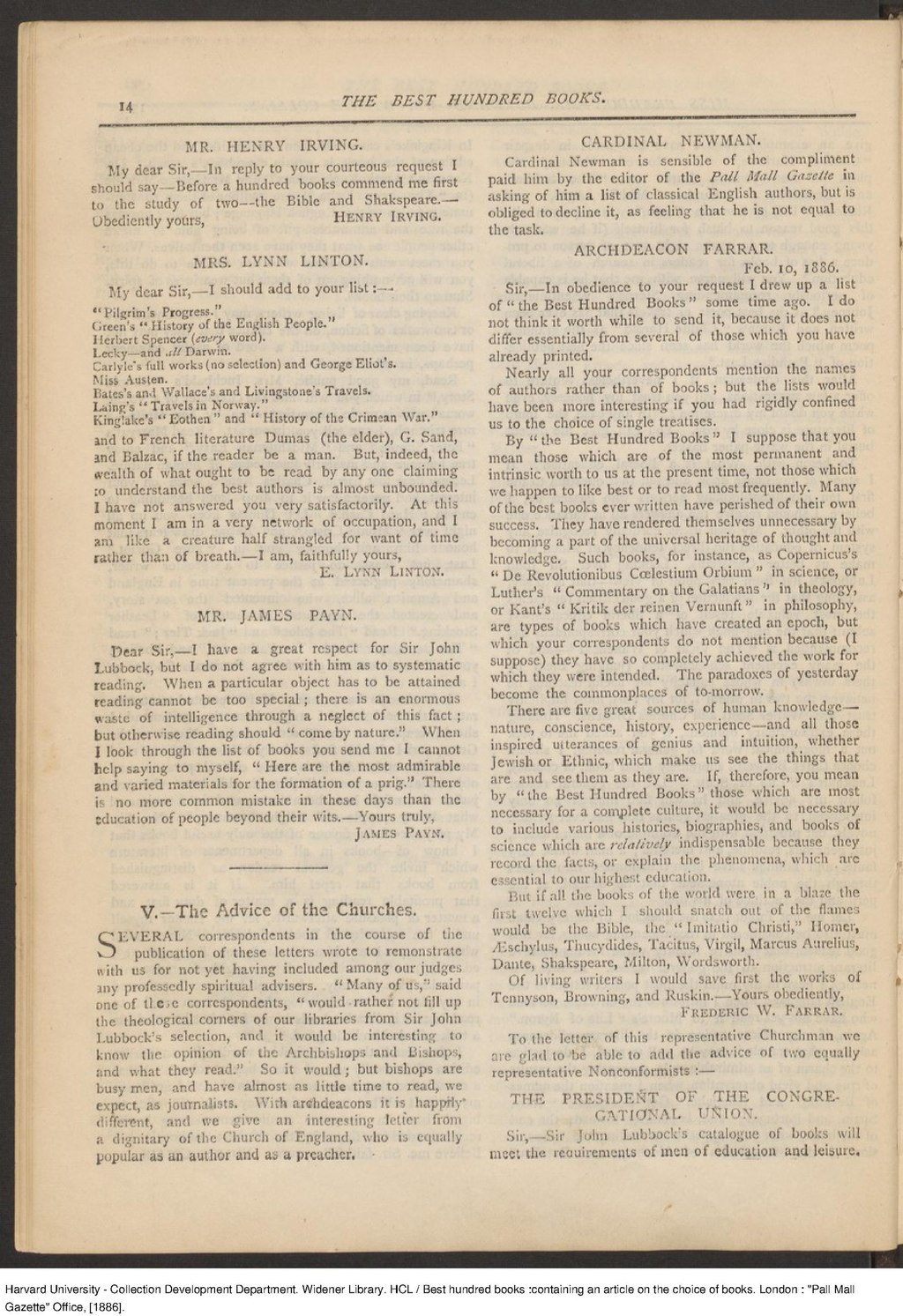

MR. HENRY IRVING.

My dear Sir,—In reply to your courteous request I should say—Before a hundred books commend me first to the study of two—the Bible and Shakspeare.—Obediently yours,

MRS. LYNN LINTON.

My dear Sir,—I should add to your list:—

"Pilgrim's Progress."

Green's "History of the English People."

Herbert Spencer (every word).

Lecky—and all Darwin.

Carlyle's full works (no selection) and George Eliot's.

Miss Austen.

Bates's and Wallace's and Livingstone's Travels.

Laing's "Travels in Norway."

Kinglake's "Eothen " and History of the Crimean War."

and to French literature Dumas (the elder), G. Sand, and Balzac, if the reader be a man. But, indeedm the wealth of what ought to be read by any one claiming to understand the best authors is almost unbounded. I have not answered you very satisfactorily. At this moment I am in a very network of occupation, and I am like a creature half strangled for want of time rather than of breath.—I am, faithfully yours,

MR. JAMES PAYN.

Dear Sir,—I have a great respect for Sir John Lubbock, but I do not agree with him as to systematic reading. When a particular object has to be attained reading cannot be too special; there is an enormous waste of intelligence through a neglect of this fact; but otherwise reading should "come by nature." When I look through the list of books you send me I cannot help saying to myself, "Here are the most admirable and varied materials for the formation of a prig." There is no more common mistake in these days than the education of people beyond their wits.—Yours truly,

V.—The Advice of the Churches.

SEVERAL correspondents in the course of the publication of these letters wrote to remonstrate with us for not yet having included among our judges any professedly spiritual advisers. "Many of us," said one of these correspondents, "would rather not fill up the theological corners of our libraries from Sir John Lubbock's selection, and it would be interesting to know the opinion of the Archbishops and Bishops, and what they read." So it would; but bishops are busy men, and have almost as little time to read, we expect, as journalists. With archdeacons it is happily different, and we give an interesting letter from a dignitary of the Church of England, who is equally popular as an author and as a preacher.

CARDINAL NEWMAN.

Cardinal Newman is sensible of the compliment paid him by the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette in asking of him a list of classical English authors, but is obliged to decline it, as feeling that he is not equal to the task.

ARCHDEACON FARRAR.

Sir,—In obedience to your request I drew up a list of "the Best Hundred Books" some time ago. not think it worth while to send it, because it does not differ essentially from several of those which you have already printed.

Nearly all your correspondents mention the names of authors rather than of books; but the lists would have been more interesting if you had rigidly confined us to the choice of single treatises.

By "the Best Hundred Books" I suppose that you mean those which are of the most permanent and intrinsic worth to us at the present time, not those which we happen to like best or to read most frequently. Many of the best books ever written have perished of their own success. They have rendered themselves unnecessary by becoming a part of the universal heritage of thought and knowledge. Such books, for instance, as Copernicus's "De Revolutionibus Calestium Orbium" in science, or Luther's "Commentary on the Galatians" in theology, or Kant's "Kritik der reinen Vernunft" in philosophy, are types of books which have created an epoch, but which your correspondents do not mention because (I suppose) they have so completely achieved the work for which they were intended. The paradoxes of yesterday become the commonplaces of to-morrow.

There are five great sources of human knowledge—nature, conscience, history, experience—and all those inspired utterances of genius and intuition, whether Jewish or Ethnic, which make us see the things that are and see them as they are. by "the Best Hundred Books" those which are most necessary for a complete culture, it would be necessary to include various histories, biographies, and books of science which are relatively indispensable because they record the facts, or explain the phenomena, which are essential to our highest education.

But if all the books of the world were in a blaze the first twelve which I should snatch out of the flames would be the Bible, the "Imitatio Christi," Homer, Æschylus, Thucydides, Tacitus, Virgil, Marcus Aurelius, Dante, Shakspeare, Milton, Wordsworth.

Of living writers I would save first the works of Tennyson, Browning, and Ruskin.—Yours obediently,

To the letter of this representative Churchman we are glad to be able to add the advice of two equally representative Nonconformists:—

THE PRESIDENT OF THE CONGREGATIONAL UNION.

Sir,—Sir John Lubbock's catalogue of books will meet the reauirements of men of education and leisure,