animals; the side cases filled with the grand procession of organised life, from the vegetable to the highest order of animal life; the upper galleries shining with a vast army of bottles, the depositories of Nature’s more subtile secrets; the shelves full of monstrosities and malformations, and the glass-cases rich in physical curiosities illustrative of the accidents to which life is subjected. Here a series of tadpoles, from the time the creature leaves the ovum to that period of adolescence when, contrary to the human example, it casts its tail; there a couple of gigantic American elk horns, fast locked in conflict,—the doe for whom the animals had been fighting was found dead beside the entangled belligerents; a little further on the skeleton of poor Chunee—the hapless elephant who suffered death at Exeter Change for the crime of having a toothache—his skull riddled with balls, showing that the file of soldiers who did the murder were not possessed of the skill of the great hunter, Gordon Cumming, who dropped his elephant of a hundred summers with one ball judiciously planted. Turn which way he will, where in fact all is order, he sees nothing but confusion. Under these circumstances we cannot do better than take the visitor by the hand, and let his attention fall naturally upon the most prominent objects.

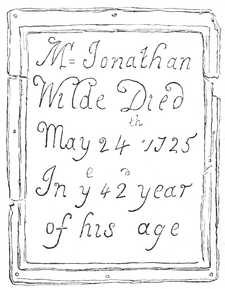

There is evidently a natural determination of giants towards the museum. The most striking object the eye meets on entering the first large room is the skeleton of the Irish giant, O’Bryan. His fate was a memorable example of how vain is the struggle men of such extravagant development wage against the anatomist. Poor O’Bryan, who drank himself to death, evidently had a presentiment of the manner in which his body would be disposed of; and he tried to avert it by directing that his body should be sunk in the deep, and in order to provide for this disposition of it, two men were provided to watch it until the time for the burial came. But Hunter could not bring himself to let slip such an opportunity to acquire such a “specimen,” and he attempted to bribe the wretches by offering them a hundred pounds for it. His eagerness was too apparent however, and these trustworthy individuals managed to raise the price to 800l.! The prize obtained, Hunter sent it home in his own carriage, and fearing lest it should be claimed, immediately dismembered, and boiled it. The writer of the description in the catalogue apologetically refers to the consequent brown appearance of the skeleton, in the same spirit as a clear-starcher would of the unsatisfactory “get up” of a piece of fine linen. It does not appear to make much difference to O’Bryan, however, who is posed in an easy attitude, with one arm hanging carelessly by his side, and the other held elegantly aloft, towering by the head and shoulders over another “rough sketch of man,” which stands upon an opposite pedestal. In the glass cases which fill the left-hand corner of the upper end of the room, other giants with a commendable modesty keep in the back ground. Freeman, the American pugilist, as far as the whiteness of his bones is concerned, cannot complain of his “getting up;” and in the other corner a gigantic tinker forms a becoming pendant. This man when in the flesh used to pass by the college, and do odd jobs, and in return he is conveniently housed in this comfortable glass case. At the bottom of the glass case we see the outstretched hands of other giants marked—the English giant, Bradley; the French giant, Mons. Lewis, seven feet four inches; the Irish giant, Patrick Cotter, eight feet seven inches. They seem to hold up their hands in testimony of their stature ere they finally subside to the level of mother earth. But what is there particular about that rather short and powerful skeleton between the two larger ones? The attendant takes out his card, which lies against the wall in the shape of a coffin-plate thus inscribed:—

The card forgets to give his last address, doubtless from motives of delicacy. Tyburn was not such a fashionable neighbourhood then, as it has since become. There is nothing about the present appearance of the great thief-catcher which at all reminds one of his bad pre-eminence in life. In all probability, many of the skeletons about him were those of thieves and murderers; for of old the Conservator of the museum was dissector in ordinary to all malefactors executed in London. Nevertheless, Wilde seems no longer to scent his prey, and the hunter and hunted are at last at peace,—at least when they are not being dusted, which I am assured is done by one of the porters three times a year with the utmost impartiality. In an adjoining glass-case there are specimens of Australian and African skeletons, which present certain differences from the European type which are highly interesting to the comparative anatomist. How clearly we see the countenance of the Bosjesman in the facial bones of the skull, and how feeble is the framework of the Australian savage when compared with that of the European, enervated, as some people choose to say, with an ultra civilisation. At the opposite end of this room there are some human mummies, which we must not omit to notice. For instance, there stands Mrs. Van