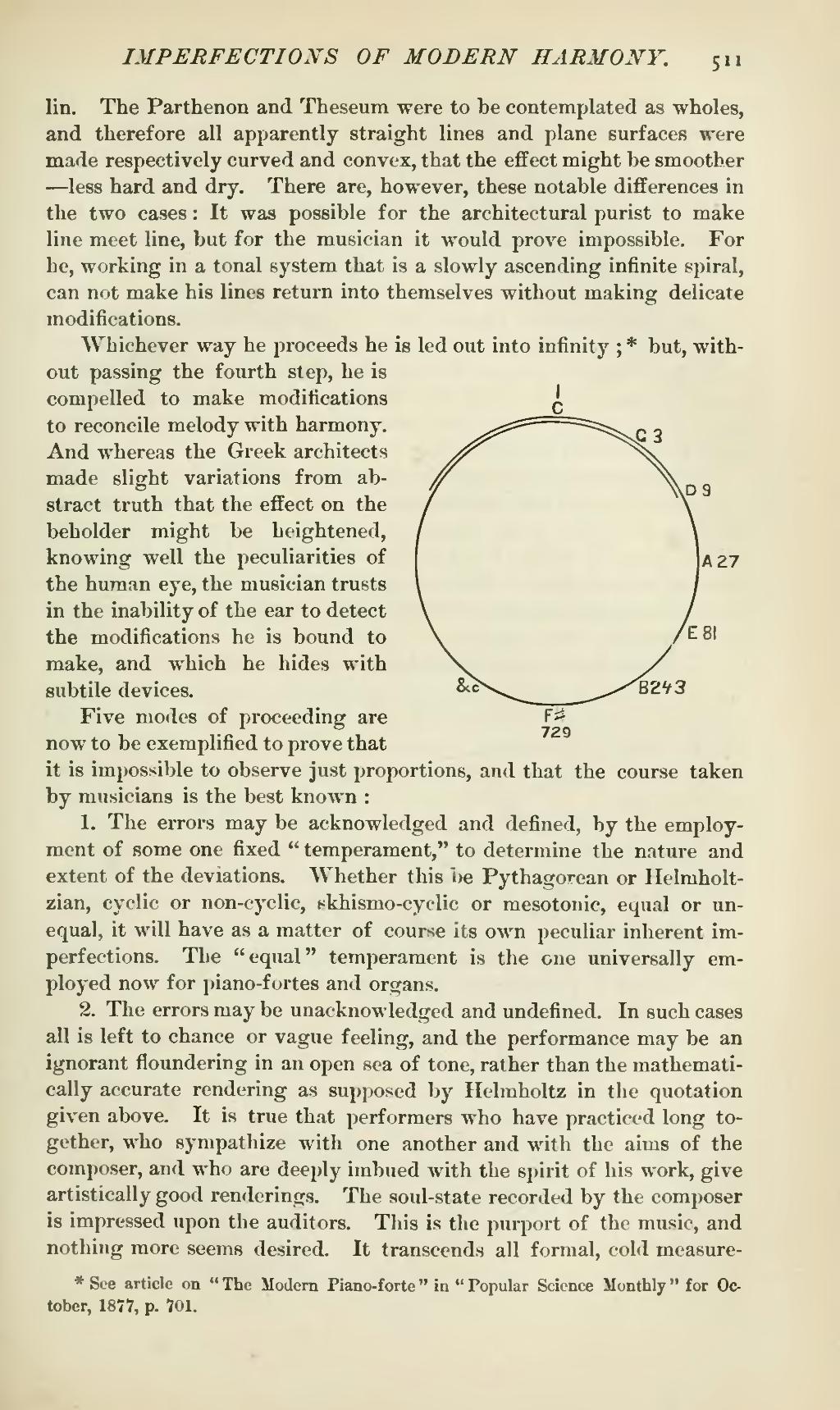

lin. The Parthenon and Theseum were to be contemplated as wholes, and therefore all apparently straight lines and plane surfaces were made respectively curved and convex, that the effect might be smoother—less hard and dry. There are, however, these notable differences in the two cases: It was possible for the architectural purist to make line meet line, but for the musician it would prove impossible. For he, working in a tonal system that is a slowly ascending infinite spiral, can not make his lines return into themselves without making delicate modifications.

Whichever way he proceeds he is led out into infinity;[1] but, without  passing the fourth step, he is compelled to make modifications to reconcile melody with harmony. And whereas the Greek architects made slight variations from abstract truth that the effect on the beholder might be heightened, knowing well the peculiarities of the human eye, the musician trusts in the inability of the ear to detect the modifications he is bound to make, and which he hides with subtile devices.

passing the fourth step, he is compelled to make modifications to reconcile melody with harmony. And whereas the Greek architects made slight variations from abstract truth that the effect on the beholder might be heightened, knowing well the peculiarities of the human eye, the musician trusts in the inability of the ear to detect the modifications he is bound to make, and which he hides with subtile devices.

Five modes of proceeding are now to be exemplified to prove that it is impossible to observe just proportions, and that the course taken by musicians is the best known:

1. The errors may be acknowledged and defined, by the employment of some one fixed "temperament," to determine the nature and extent of the deviations. Whether this be Pythagorean or Helmholtzian, cyclic or non-cyclic, skhismo-cyclic or mesotonic, equal or unequal, it will have as a matter of course its own peculiar inherent imperfections. The "equal" temperament is the one universally employed now for piano-fortes and organs.

2. The errors may be unacknowledged and undefined. In such cases all is left to chance or vague feeling, and the performance may be an ignorant floundering in an open sea of tone, rather than the mathematically accurate rendering as supposed by Helmholtz in the quotation given above. It is true that performers who have practiced long together, who sympathize with one another and with the aims of the composer, and who are deeply imbued with the spirit of his work, give artistically good renderings. The soul-state recorded by the composer is impressed upon the auditors. This is the purport of the music, and nothing more seems desired. It transcends all formal, cold measure-

- ↑ See article on "The Modern Piano-forte" in "Popular Science Monthly" for October, 1877, p. 701.