17

One of the greatest difficulties in the treatment of female offenders is the fact that, compared to men, they enter upon a criminal career at a much later age, and thus frequently at the outset overstep the period within which they could, as juvenile offenders, be subjected to reforming influences.∗

On this point Morrison says:—"The criminal age among women is later in its commencement because of the greater care and watchfulness exercised over girls than boys; but it is more persistent while it lasts, because the plunge into crime is a more irreparable thing in a woman than in a man. . . . . If it is important to keep men as much as possible out of prison, it is doubly necessary to keep out women; but it is, at the same time, a much harder thing to accomplish. This arises from the fact that the great bulk of female offenders enter the criminal arena after the age of 21, and can only be dealt with by a sentence of imprisonment. If females began crime at any earlier period of life it would be possible to send them to reformatories or industrial schools, and a fair hope of saving them would still remain."

Undoubtedly the heavy social penalties involved by imprisonment press much more severely upon women than upon men, and for that reason a much briefer term of incarceration is necessary in their case than in the case of men, in order to attain the same punitive results.

We recommend that in the case of first offences by women all who are under the age of eighteen should be treated in reformatories.

Your Commissioners were favored by Commandant Booth, of the Salvation Army, with some particulars of the work done by the organisation, of which this witness is a recognised representative. From the Commandant we gather that the Salvation Army is prepared, if required, to take over all or any of the children now in the Reformatory or Industrial Schools of the Colony, and to relieve the State of their charge in return for an allowance of 7s. 1012d. per week per head for the Industrial School children, and of 10s. 6d. per week for the Reformatory children. We invite attention to Commandant Booth's evidence on this point, which is as follows:—

"The Victorian system has abolished all Government Reformatories and Schools. There is nothing but a central depot. The children are committed to the department and lodged in the depot until the officer in charge allocates them. The neglected children are boarded out, and the criminal children and a certain proportion of the neglected children, who are not suitable for boarding out, are sent to semi-Government institutions controlled by private persons. We have thirty boys at one farm. They are warded to me as constituted head of the Salvation Army until they are 18. While they are with us we get 10s. a week for each boy and £5 for an outfit for him when he leaves the home. . . . . The children practically gradually merge into the ordinary population. . . . . . We have 260 children under our charge in Victoria. We would be prepared to take charge of the children here at 10s. 6d. a week from the reformatory and 7s. 1012d. from the industrial schools."

If this proposal were entirely experimental in its character we should hesitate to recommend the consideration, even in a modified form, of a scheme so entirely subversive of the arrangements at present made by the State for the treatment of juvenile offenders and the young waifs and strays for whose maintenance and training it is responsible. The Salvation Army, however, claims to have done much good service in this direction in the eastern colonies, where the Governments concerned have handed over a number of children to its charge; and we would suggest that it would be desirable to communicate with the Governments of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland in order to ascertain what, if any, modifications may be shown by experience to be desirable if it should be decided to accept the proposals of the Salvation Army. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that as special provision is already made for the committed children of Roman Catholic parents, it is questionable whether any difficulties would arise on religious grounds with reference to children who might be handed over to the Salvation Army.

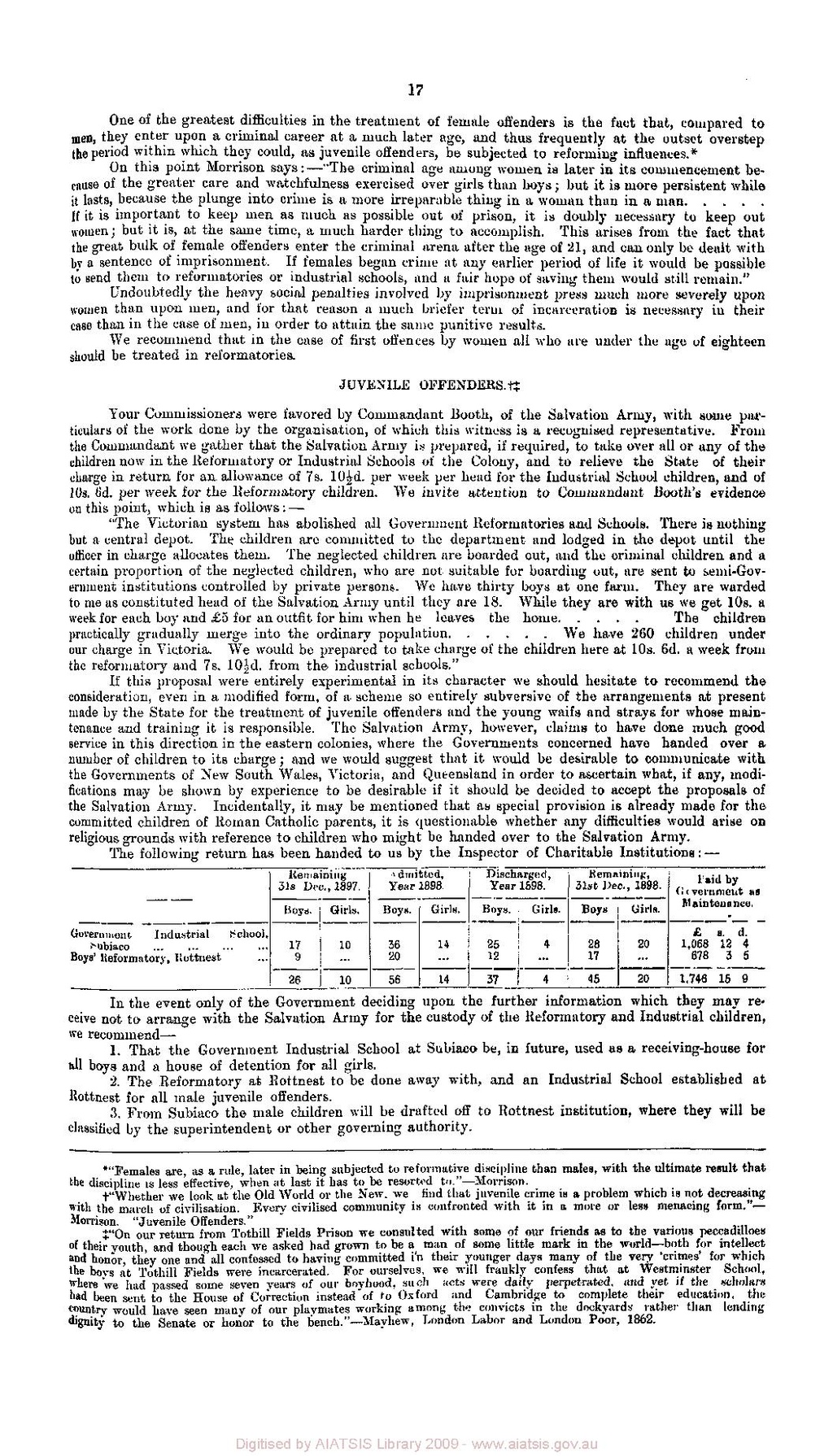

The following return has been handed to us by the Inspector of Charitable Institutions:—

| Remaining 31s Dec., 1897. |

Admitted, Year 1898. |

Discharged, Year 1898. |

Remaining, 31st Dec., 1898. |

Paid by Government as Maintenance | |||||||

| Boys. | Girls. | Boys. | Girls. | Boys. | Girls. | Boys. | Girls. | ||||

Government Industrial School,

Subiaco. . .. . .. . .. . . |

£ | s. | d. | ||||||||

| 17 | 10 | 36 | 14 | 25 | 4 | 28 | 20 | 1,068 | 12 | 4 | |

| Boys' Reformatory, Rottnest. . . | 9 | . . . | 20 | . . . | 12 | . . . | 17 | . . . | 678 | 3 | 5 |

| 26 | 10 | 56 | 14 | 37 | 4 | 45 | 20 | 1,746 | 15 | 9 | |

In the event only of the Government deciding upon the further information which they may receive not to arrange with the Salvation Army for the custody of the Reformatory and Industrial children, we recommend—

- That the Government Industrial School at Subiaco be, in future, used as a receiving-house for all boys and a house of detention for all girls.

- The Reformatory at Rottnest to be done away with, and an Industrial School established at Rottnest for all male juvenile offenders.

- From Subiaco the male children will be drafted off to Rottnest institution, where they will be classified by the superintendent or other governing authority.

∗7 "Females are, as a rule, later in being subjected to reformative discipline than males, with the ultimate result that the discipline is less effective, when at last it has to be resorted to."—Morrison.

†6 "Whether we look at the Old World or the New, we find that juvenile crime is a problem which is not decreasing with the march of civilisation. Every civilised community is confronted with it in a more or less menacing form."—Morrison. "Juvenile Offenders."

‡6 "On our return from Tothill Fields Prison we consulted with some of our friends as to the various peccadilloes of their youth, and though each we asked had grown to be a man of some little mark in the world—both for intellect and honor, they one and all confessed to having committed in their younger days many of the very 'crimes' for which the boys at Tothill Fields were incarcerated. For ourselves, we will frankly confess that at Westminster School, where we had passed some seven years of ourboyhood, such acts were daily perpetrated, and yet if the scholars had been sent to the House of Correction instead of to Oxford and Cambridge to complete their education, the country would have seen many of our playmates working among the convicts in the dockyards rather than lending dignity to the Senate or honor to the bench."—Mayhew, London Labor and London Poor, 1862.