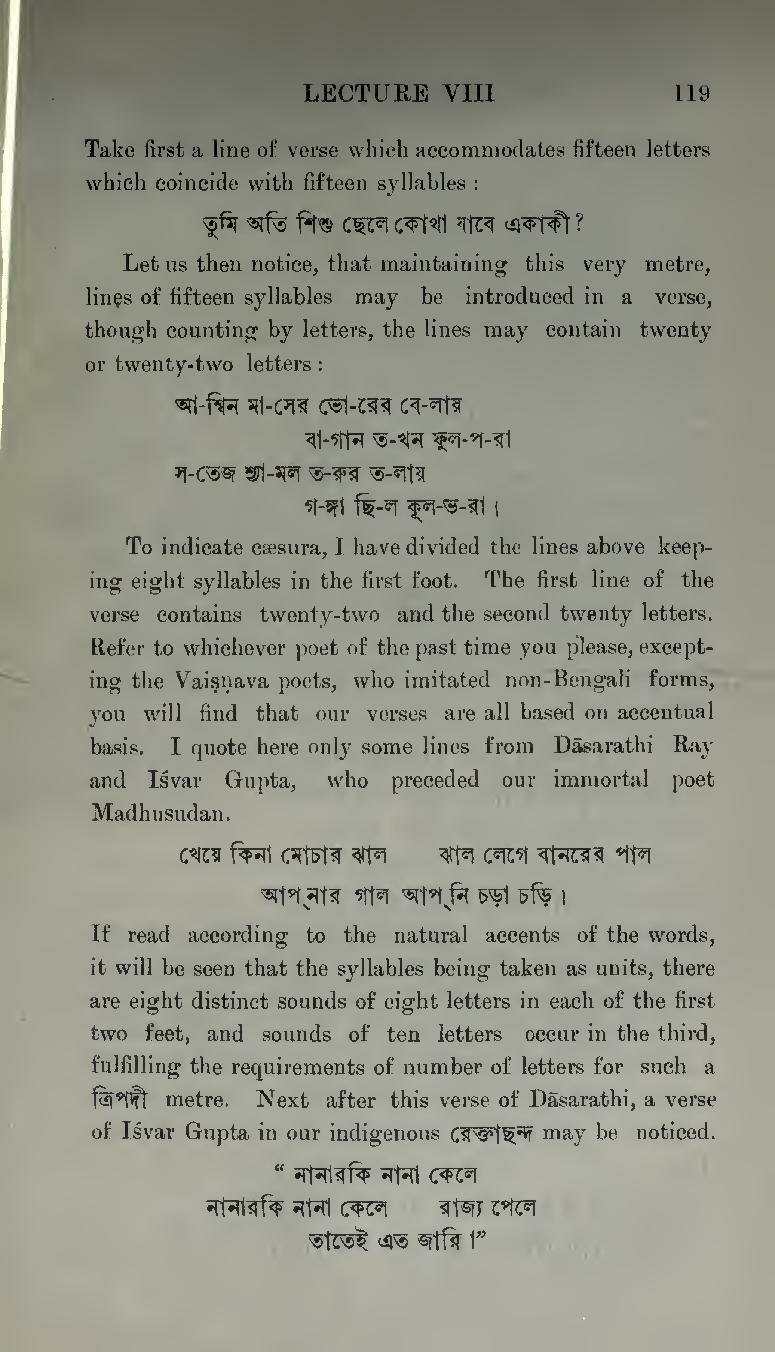

Take first a line of verse which accommodates fifteen letters which coincide with fifteen syllables:

তুমি অতি শিশু ছেলে কোথা যাবে একাকী?

Let us then notice, that maintaining this very metre, lines of fifteen syllables may be introduced in a verse, though counting by letters, the lines may contain twenty or twenty-two letters:

আ-শ্বিন মা-সের ভো-রের বে-লায়

- বা-গান ত-খন ফুল-প-রা

- বা-গান ত-খন ফুল-প-রা

স-তেজ শ্যা-মল ত-রুর ত-লায়

- গ-ঙ্গা ছি-ল কূল-ভ-রা।

To indicate cæsura, I have divided the lines above keeping eight syllables in the first foot. The first line of the verse contains twenty-two and the second twenty letters. Refer to whichever poet of the past time you please, excepting the Vaiṣṇava poets, who imitated non-Bengali forms, you will find that our verses are all based on accentual basis. I quote here only some lines from Dāsarathi Ray and Iśvar Gupta, who preceded our immortal poet Madhusudan.

খেয়ে কিনা মোচার ঝালঝাল লেগে বানরের পাল

আপ্নার গাল আপ্নি চড়া চড়ি।

If read according to the natural accents of the words, it will be seen that the syllables being taken as units, there are eight distinct sounds of eight letters in each of the first two feet, and sounds of ten letters occur in the third, fulfilling the requirements of number of letters for such a ত্রিপদী metre. Next after this verse of Dāsarathi, a verse of Iśvar Gupta in our indigenous রেক্তাছন্দ may be noticed.

"নানারকি নানা কেলে

নানারকি নানা কেলেরাজ্য পেলে

তাতেই এত জারি।"