Popular Science Monthly/Volume 78/January 1911/The Progress of Science

ACADEMIC AND INDUSTRIAL EFFICIENCY

The Carnegie Foundation is certainly doing what it can to disturb the somnambulance which is supposed to characterize academic circles. It promises length of service pensions to professors and then decides not to pay them; its trustees pass resolutions and quite different action is announced in the annual report; it tells universities to do this, that and the other, if they want its pensions. There was recently published a report informing us that most of the medical schools in the country should be suppressed, and we now have a bulletin telling us how universities should introduce the industrial efficiency which the author optimistically assumes to characterize our manufacturing concerns.

This publication, like others from the same source, is really interesting. It is an advantage for academic problems to be discussed from all sides and that complete publicity should be given to financial management. It is, however undesirable for an institution having largesses to bestow to assume powers either inquisitorial or dictatorial. In the present case it is fair to state that the president of the foundation says that ne refrains from discussing the merits of the report made and published under its direction.

The author, Mr. M. L. Cooke, is an engineer who specializes in the organization and management of industrial establishments. He takes himself and his methods so seriously that it is difficult to treat them with the consideration which they may deserve. It is evident from the principle of the "cost per unit hour" that a university in which a thousand-dollar instructor is teaching a hundred students is five hundred times as efficient as one in which a five-thousand-dollar professor is proposing a problem for research to a single man; but it is not clear how one can deduce from this principle that "there is a distinct disadvantage to undergraduate students to be near research work." But perhaps this is because research work does not set an example of efficiency, the universities not yet having adopted Mr. Cooke's plan of a "general research board" and "a director of research," "to pass on the expediency of undertaking any given project, and to keep constant track of the progress of work and of its cost."

Mr. Cooke commends one professor who told him "that if at a lecture the students began to get drowsy, he gave them a little more air," but it is not clear that the cost per unit hour would have been increased if the air had been let in sooner. This particular professor is also highly praised for keeping his lecture-room extraordinarily neat; but it appears elsewhere in the report that under these circumstances he required four assistants to help in the preparation of a lecture.

We are told by Mr. Cooke that only at one university "was there anything to impress me with the snap and vigor of the business administration." If the tables in the report are correct, this university pays its teachers less than Harvard, but spends more than twice as much in its administration, namely, $258,456.12 a year, about half what it pays its teachers. This university, the combined cost of whose administration and teaching is greater than at Harvard, has about half as many scientific men of distinction on its faculty. Indeed, in one case at least Mr. Cooke's observation is not bad, for he naively says: "At those schools where there were the largest number of "big men" I found what seemed to me to be the least desirable systems of management." Mr. Cooke would remedy this by arranging matters so "that when a man has ceased to be efficient he must be retired, as he would in any other line of work "but he does not tell us who would be responsible for dismissing professors or whether under these circumstances professors in our leading universities might not properly expect salaries equal to those of our leading engineers, physicians and lawyers.

It should be understood that these remarks and quotations give only one side of Mr. Cooke's report, which is in many respects a document worth reading. The usefulness of our universities should be increased; their money is not always spent to the best advantage. It seems to be generally true that efficiency is inversely as the size of the "concern." The writer of this note has recently had dealings with a department store, a publishing house and an express company, and he can assure Mr. Cooke and the Carnegie Foundation that there is even more urgent need for missionary labors on behalf of efficiency elsewhere than in the university. Efficiency is desirable everywhere; but it is only a means to an end. The university stands for higher things—scholarship, research, service, leadership, ideals, honor. It is doubtful whether the further elaboration of department-store methods in the university will even reduce the "cost per unit hour," if "overhead charges" are included. The solution is the reverse of that proposed by Mr. Cooke. The department should have autonomy and the individual freedom. Only thus will the best men be drawn to the universities and be led to do their best work.

THE MOUNT WILSON CONFERENCE OF THE SOLAR UNION

The fourth conference of the International Union for Solar Research was held at the Solar Observatory of the Carnegie Institution, Mount Wilson, California, from August 31 to September 2, 1910. The attendance was large, 37 delegates from eleven foreign countries being recorded on the official list, together with 46 Americans. Many of the latter, though not members of the union, had accepted its invitation to attend the conference.

Nearly half the delegates crossed the continent together, as many had attended the meeting of the Astronomical and Astrophysical Society of America at Harvard (August 17-19). This afforded opportunities for informal conferences and discussions almost equal in value to those provided by the conference itself.

On Monday, August 29, the members of the conference visited the laboratories and shops of the Solar Observatory, which are in Pasadena at the foot of the mountain. Among the things of greatest interest may be mentioned the exceedingly well-equipped spectroscopic laboratory, the massive machinery for grinding the great 100inch mirror and a wealth of photographs, some of which showed the enormous light-gathering power of the great 60-inch reflector now installed on the mountain.

The afternoon was pleasantly occupied by a garden party given by Professor and Mrs. Hale, and on the following morning the party, numbering nearly 100, began the 5,000-foot climb to the observatory, some in carriages, some on horseback and a few hardy souls on foot. The hotel on the summit, though crowded to the limit, provided all with very comfortable accommodation.

No formal papers were read at the sessions of the conference, which were devoted to the reports of committees and to questions of general policy; but the larger part of the day was free for conferences of an informal nature, which were most valuable, especially to the younger men.

The first official session was on Wednesday morning. Professors Pickering, Campbell and Frost (directors of the Harvard, Lick and Yerkes observatories) were elected chairmen for the three days of the meeting, and Messrs. Puiseux (of Paris), Konen (Münster) and Adams (Mt. Wilson), secretaries of the meeting. All formal business was announced in English, French and German, and the three languages were used in the discussions, which emphasized the international character of the gathering.

Dr. Hale made the opening address. He welcomed the visitors to the observatory, and described the work in progress there, dwelling especially on the recent discoveries that sun-spots are the centers of a vortical movement in the upper layers of the solar atmosphere, and the seat of strong magnetic fields, and describing the new "tower telescope," of 150 feet focal length, mounted vertically on a tower, every member of whose framework is completely surrounded by that of an outer tower, protecting it from vibration and other disturbances, while the spectroscopic apparatus, of 75 feet focal length, is in a deep well under the tower, effectually protected from changes of temperature and other perturbations.

The report of the committee on standard wave-lengths was presented by Professor Kayser (Bonn), and it was voted that when three independent measurements by the interference method of the lines of the iron arc are available, the arithmetical mean of the three shall be adopted as international standards of the second order (Michelson's determination for the red cadmium line being the primary standard). Standards of the third order are to be determined by interpolation between these and a complete system of very exact reference points throughout the spectrum thereby obtained.

Dr. Abbot, of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory on Mount Wilson, lectured that evening on the solar constant of radiation, and presented a committee report dealing with the same subject on the following morning. After correcting for the absorption of heat in passing through our atmosphere (a very difficult problem, now in a fair way toward solution) the heat received from the sun appears to be slightly less than two gram-calories per square centimeter per minute. The Mount Wilson observations, however, show changes of short and irregular period (a few days) which exceed the errors of observation. It is exceedingly desirable to establish a second station some distance away (say in Mexico) where simultaneous observations may be made, to determine whether these changes are of solar or atmospheric origin.

The report of the committee on the spectra of sun-spots was presented by Professor Fowler (South Kensington). The principal feature of interest was the remarkable constancy, even in small details, of the spectrum shown by different spots.

On the second evening (Thursday) Professor Kapteyn (Groningen) lectured on "Star-streams among Stars of the Orion Type," showing that in a large region of the southern sky (including Scorpio, Centaurus and the Southern Cross) 85 per cent, of the stars of this spectral type (supposed to be the hottest) are moving together in space, their actual motions being very nearly equal and parallel; while in Perseus and neighboring constellations 95 per cent, of the stars of the same type have a similar common drift, but of different magnitude and direction. The velocity of these drifts can be found from spectroscopic observations, which makes it possible to determine the distances of these remote stars, which in some cases appear to be as great as 500 light-years—far beyond the possibility of direct measurement.

On Friday reports from committees on solar rotation and on spectroheliographic work were presented, and, the regular business being at an end. the question of tho extension of the work

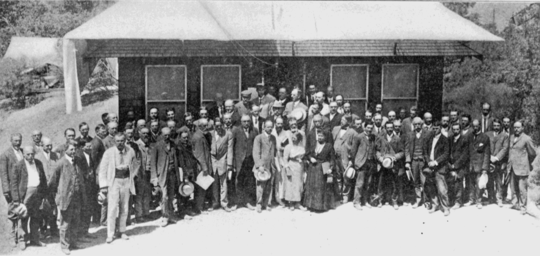

Astronomers on Mount Wilson

Dr. Hale near the center; on his left Mrs. Kapteyn and Mrs. Fleming; on his right Messrs. Pickering, Backlung, Kayser and Turner; further on Messrs. Rydberg, Wolfer, Küstner, Hartmann, Pulseux and Frost. Above near the door, are Messrs. Ames, Kosen, Fowler, Deslanres, Belpolsky, Campbell, Ricco, Schwarzschild and Schlesinger. Further to the left are Messrs. Fabry, Hills, Abbot, Larmor, Dyson, Barnard, Newell and Pringsheim.

of the union to the study of stellar spectra was discussed at some length. Opinion in favor of such a step appeared to be almost unanimous, and, on motion of Professor Schwarzschild (Potsdam), it was formally resolved "that the Solar Union extend its sphere of activity so as to include astrophysics generally," and this was followed up by the appointment of a committee on the classification of stellar spectra.

Invitations to hold the next meeting at Bonn, Barcelona and Rome were presented, and it was decided to meet at the first, in the summer of 1913—the exact date to be determined by the executive committee.

The former committees of the union were in most cases reappointed, a number of new members being added. The new committee on stellar spectra i includes Messrs. Pickering (chairman),] Adams, Campbell, Frost, Hale, Hamer, j Hartmann, Kapteyn, Küstner, Newall, Plaskett, Russell, Schlesinger (secretary) and Schwarzschild, with power] to add to their number.

Resolutions of thanks—proposed in very felicitous speeches—completed the business, and the conference adjourned, to reassemble on Saturday evening at Pasadena as the guests of Dr. and Mrs. Hale at a dinner, which brought the proceedings to a close.

The only cloud upon an otherwise flawless week was the ill-health of Dr. Hale, who was able to attend only the opening session of a conference whose success was above all things the result of his hospitable preparations.

SCIENTIFIC ITEMS

We record with regret the deaths of Dr. Charles Otis Whitman, head of the department of zoology of the University of Chicago and lately director of the Woods Hole Marine Biological Station; of Dr. Christian Archibald Herter, professor of pharmacology and therapeutics in the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University; of Dr. Octave Chanute, of Chicago, known for his important contributions to scientific aviation, and of Dr. Angelo Mosso, professor of physiology in the University of Turin.

A memorial has been erected at the National Bacteriological Institute in the City of Mexico to Howard T. Ricketts, who at the time of his death was assistant professor of pathology in the University of Chicago and professor-elect of pathology in the University of Pennsylvania. His death was caused by typhus fever, which he contracted while conducting researches in this disease.

Dr. Edgar F. Smith, for twenty-two years professor of chemistry in the University of Pennsylvania and for twelve years vice-provost, has been elected provost in succession to Dr. C. C. Harrison.—Mr. R. A. Sampson, F.R.S., professor of mathematics and astronomy in the University of Durham, has been named astronomer royal for Scotland in succession to Mr. F. W. Dyson, F.R.S.

At the celebration of the centenary of the University of Berlin degrees were conferred on three American men of science—the degree of doctor of philosophy on Dr. George E. Hale, director of the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory, and on Dr. Bailey Willis, of the U. S. Geological Survey, and the degree of doctor of medicine and surgery on Dr. Theodore W. Richards, professor of chemistry in Harvard University.—Dr. Henry F. Osborn, of Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History, and Professor E. B. Wilson, of Columbia University, have been elected corresponding members of the Munich Academy of Sciences.—Mme. Curie is a candidate for the fauteuil at the Academy of Sciences, rendered vacant by the death of M. Gernez.