The Royal Navy, a History from the Earliest Times to the Present/Volume 1/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II.

MILITARY HISTORY OF NAVAL AFFAIRS TO 1066.

But the annihilation of their fleet was not the only evil brought upon the Britons by their interposition in favour of the Veneti. They had inopportunely reminded Cæsar of their existence, within sight of the shores which he was then engaged in pacifying, and as soon as he had made sufficient progress with that part of his task, he turned his attention to the island across the Strait of Dover. This was in b.c. 55.[2]

Learning or suspecting the designs of Cæsar, the Britons dispatched an embassy to him professing friendliness, and offering hostages. He returned an answer which, while it encouraged them to be peaceful, did not commit him, and soon afterwards he sent Caius Volusenus in a light craft to reconnoitre the shores of the island, and collected transport for two legions. In five days Volusenus returned with information, and Cæsar, ordering the troops on board, sailed at about one o'clock one morning from Portus Iccius, now probably Wissant Bay,[3] and at ten found himself under high cliffs, which were crowned by numbers of the enemy in arms. The whole of his fleet had not then come up, nor did he deem it prudent to attempt a landing where the superior position held by the defence would have told heavily against the assailants. Indeed, if, as is most probable, he struck the coast between Dover and the South Foreland, it would have been impossible for him, had he landed on the beach, to gain the top of the cliff, for even to-day there is no way thither. He therefore anchored so as to allow his flotilla to collect, and after a brief delay, called a council of war, communicated and doubtless discussed the intelligence brought him by Volusenus, and, as soon as wind and tide served, weighed to the north-east.

A few miles farther he discovered a plain and open shore to suit his purpose. The spot was probably a little to the southward of where now stands Walmer Castle[4] The Britons seem to have followed along the coast as the fleet advanced, with their cavalry and chariots in the van, and their infantry in the rear, and to have arrived as soon as the ships, and occupied the beach in force.

ROMAN LIBURNA, OR GALLEY, WITH ONE TIER OF OARS.

(After Basius.)

Landing was difficult, the draught of the transports not permitting them to draw very near the land; and the men, laden with arms and armour, were obliged to jump into comparatively deep water and wade ashore, harassed not only by the breakers but also by the foe, who rode their horses down to the edge of the surf, or waded in afoot to meet the Romans. Under this kind of treatment the attack wavered, whereupon Cæsar sent his lightest galleys as close in as possible, and so stationed them that with their slings and other engines they took the Britons in flank. The effect was soon felt. The defence began to give way, and when the standard-bearer of the Tenth Legion invoked the gods, and dashed into the water shouting, "Follow me, comrades, unless you would abandon your eagle to the enemy, for I, on my part, am determined to do my duty to my country and my general"; he did not appeal in vain. Soon many of the legionaries reached dry ground, and presently the Britons fled, and from a safe distance sent ambassadors with hostages to sue for peace. On the fourth day a treaty was concluded.

Cæsar encamped, apparently, near his place of landing. He was expecting reinforcements in the shape of cavalry, the eighteen transports assigned to which had not been ready to sail with the rest of the fleet. The squadron was within sight of the camp when it was dispersed and ultimately driven back by a sudden and violent storm. Nor was this the only cause of anxiety. On the same night there was a spring tide, which the invaders had omitted to provide against, and this, together with the storm, damaged the lighter vessels which were hauled up on the beach, and drove from their anchors several of those which were riding off shore, causing some of them to founder, and dismasting others. Cæsar had with him no facilities for refitting his vessels, and no provision for wintering in Britain, and the British chiefs, conscious of this, did not scruple to break the treaty, and to attack with their whole force. The Roman position was precarious, but two or three indecisive skirmishes led up to a pitched battle, in which the Britons were completely defeated. Once more they begged for peace. Cæsar ordered them to send to Gaul twice as many hostages as had before contented him, and then, feeling that, as the autumn equinox was upon him, further delay would be dangerous, took advantage of the first fair wind, and, weighing with the remnants of his fleet, returned safely to Gaul after a few hours' passage.

Such was the first descent of the Romans. It showed how easy and open lay the way to this country, when only the white cliffs and the exertions of people on land perplexed the enemy. Had the Britons been able to oppose fleet with fleet, the result might have been very different; for Cæsar's ships were crowded, could not have been in the best fighting trim, and while crossing the Channel, did not keep, in company, and might perhaps have been dealt with in detail. But the British fleet had been expended at the mouth of the Loire before Cæsar had formed any definite designs against Britain. Still, it is remarkable that there was no opposition whatsoever afloat. Not a single British ship is reported to have been so much as sighted. It is impossible to conceive that no ship remained in the country, and what happened can only be explained upon the assumption that the seafaring districts, which were then chiefly, so far as can be gathered, to the westward, were either at enmity with the men of Kent, or received no intelligence of the intentions of the Romans. That even Kent did possess vessels of some kind, though perhaps no warships, is evident from the fact that it sent over an embassy before Cæsar quitted the Gallic coasts, and that almost immediately after his first invasion, it dispatched to Gaul some, but not all, of the hostages whom he had demanded.

Cæsar caused preparations to be made during the autumn for another descent in B.C. 54. He himself went to Illyria; his troops wintered in Belgic Gaul; his old ships were repaired at Portus Iccius, and new ones of shallower draught and broader beam, suitable for carrying burden as well for being hauled ashore, were built. Rigging and stores for these was ordered from Spain. Returning in the spring, Cæsar found all ready, and as the Britons had not sent over all the hostages whom they had agreed to send, he had a pretext for an immediate renewal of operations. He left Labienus with three legions and two thousand horse to hold Portus Iccius, and to watch the Gauls, and, himself embarking with a similar force of cavalry and five legions, he weighed at about sunset with a light gale from the south-west, which, however, died way towards midnight. The consequence was that he found at break of day that the tide or the currents had taken him too far to the eastward; but thanks to the hard work of the men at the oars, he gained the British coast at about noon, and landed at the same place as before.

He had with him six hundred transports, besides other vessels, some of which had been fitted out by private persons for their own use, making upwards of eight hundred in all. No enemy was visible, either afloat or on shore, but it afterwards appeared from the reports of prisoners that the Britons had assembled in great numbers on the coast, and had been prepared to resist until they realised the imposing nature of the armada arrayed against them. They had then retired to the hills.[5] Cæsar therefore landed without opposition, marked out a camp close to the shore, and, having discovered the whereabouts of the foe, left Quintus Atrius with twelve cohorts and three hundred horse to guard the base, and attend to the fleet, which was anchored off shore, and himself advanced by night. He found the enemy about twelve miles inland, posted with horses and chariots on the banks of a river, which must have been the Stour at or near what is now Sandwich. An effort was made to prevent Cæsar's passage, but the Roman cavalry quickly dispersed the Britons, and drove them into the woods. Pursuit was not permitted, but scouting parties were sent out in various directions, and a camp was in process of construction, when news arrived from the base that a storm had done great damage to the fleet.

Cæsar at once recalled his men, and returned to Atrius to find that about forty vessels had been lost, and that the rest were so much disabled as to need extensive repair. He began the work immediately, sending meanwhile to Labienus for additional ships; and then, unwilling to trust the sea any longer, he with much labour and difficulty hauled every one of his craft ashore, and included all within the lines of his camp. This work occupied the troops night and day for ten days.[6] At the end of that period Cæsar again left a detachment at the base, and advanced with the bulk of his forces into the country. Near the ford where the first engagement had taken place, the Britons were found in greater strength than before, under the general command of Cassivelannus, or Caswallon, king of the Cassi. After several actions the Britons retired, apparently to the westward. Cæsar followed, keeping the Thames on his right flank until he reached a place believed by some to be Cowey Stakes, at Walton, where he saw a large body of the enemy on the opposite side of the river behind an improvised stockade, and found a ford obstructed by sharp piles. Nevertheless the Romans crossed and defeated the enemy, inflicting such punishment on Caswallon that he was obliged thereafter to restrict himself to minor operations, and to a sort of guerilla warfare. In the meantime, the Trinobantes, Cenimagni, Segontiaci, and even the Cassi, besides other tribes, submitted; and as an attempt by the Kentish chiefs upon the camp at the base had failed, Caswallon at length saw fit to treat. Cæsar, who was desirous of wintering in Gaul, accepted his opponent's submission, demanded and received hostages, arranged for the payment to Rome of a yearly tribute, and withdrew to the coast. His ships had been refitted, but all the fresh ones ordered from Labienus had not arrived, and the prisoners were numerous,

THE GOKSTAD SHIP.

View looking forward from the starboard quarter.

[To face page 20.

THE GOKSTAD SHIP.

View looking forward from the port quarter.

so that it was only by crowding his vessels that Cæsar managed to transport all his forces back to Gaul in one voyage. He made a good passage without mishap.

As in the previous year, the Britons employed no naval force against the Romans, either with a view to preventing the landing or with a view to severing Cæsar's communications with Gaul, and to obstructing the reinforcements from Labienus. The only possible conclusion is that at that time the maritime strength of south-eastern Britain was insignificant.

After Cæsar's second withdrawal, nothing further was done for many years towards the extension of Roman power in Britain. On three separate occasions Augustus meditated an expedition to the island, but he was as often prevented, either by necessity for his presence elsewhere, or by the diplomatic action of British emissaries, who net him in Gaul and promised to pay the tribute with greater regularity. Once, indeed, the ambassadors went as far as Rome itself to make their submission.[7] Again, when Cunobelinus, or Cymbeline, reigned at Camulodunum, and Caligula was Emperor, a Roman invasion appeared to be imminent; but the insane vanity of Caligula was contented with a theatrical and ridiculous demonstration on the opposite coasts;[8] and not until the time of Claudius, in A.D. 43, was any step taken towards an effective conquest of Britain.

The successive campaigns of Aulus Plautius, of Claudius himself, of Ostorius Scapula, in A.D. 50, of Suetonius Paulinus, in A.D. 58, of Petilius Cerealis, in A.D. 70, of Julius Frontinus, about A.D. 77, of Julius Agicola, from A.D. 78 to 85, and of many other leaders, were almost entirely military, and require little notice here. It will suffice to say that under Agricola,[9] the Roman naval commanders ascertained that Britain was an island; and that for a long time afterwards the Roman naval power in Britain appears to have been steadily increased, in order to secure the coasts and the surrounding seas against the Teutonic tribes, which were already distinguished for their piratical boldness, and which were later to exercise so important an influence upon the fortunes of the island.

For the repression of the Teutonic intruders, a special officer was at length appointed by the Emperors Diocletian and Maximian, probably at the beginning of their reign in 284. The first holder of the office was Caius Carausius, a man whose naval prowess had already been proved, and who was given the title of Comes Littoris Saxonici,[10] Count of the Saxon Shore. He is generally said to have been Menapian, or, as we should say, a Fleming of mean birth; but some Scots writers claim him as a Scotsman.[11]

Frankish as well as Saxon pirates scoured the North Sea and the Channel, and extraordinary powers were conferred upon Carausius to enable him to cope with them. He appears to have himself been half pirate at heart, and he may possibly have been selected in pursuance of the principle of setting a thief to catch a thief. He probably did his work well; but he did it in his own way, partly by sheer might, much more, as was declared in Rome, by subtleties of no very honourable kind; and he applied most of the spoils for his own aggrandisement.

By those methods he accumulated so much wealth and power that in 286 Maximian grew jealous of him, and employed a man to assassinate him.

The project failed, and Carausius, driven into open hostility to the Emperor, and finding a bold stroke necessary for the preservation of his liberty, determined to be an Emperor himself. He was gladly acclaimed by the local forces, both military and naval, and, acting with the energy which characterised all he did, he not only secured the whole Roman fleet of which he had held command, but also built a large number of new ships, and seized the important naval arsenal of Gesoriacum, now Boulogne, which he held as a continental outwork of his British dominions. So vigorously did he harass the empire with his squadrons, that presently, according to some writers, Maximian was glad to purchase peace at the price of formal recognition of Carausius as Emperor in Britain. There is some doubt as to the recognition; and if it was ever conceded, it was conceded only to give time to the Empire to concentrate its resources, and to create new fleets.

In the interim Britain achieved, and for a time retained, a position as a naval power of some serious importance. Carausius not only kept, but also extended, his influence, chiefly by the wise employment of his maritime strength; but, having concluded a treaty of confederation with certain rovers on the Mediterranean littoral, he frightened Maximian and his brother emperor Constantius into a renewal of active hostility.

Maximian built a large fleet in the mouths of the Rhine, and undertook the naval, while Constantius made himself responsible for the military, conduct of operations. The Emperors besieged their rival in Boulogne. They could do little on the land side, and at first, the sea being open to Carausius, he was in no danger from failure of supplies. But after a time, the besiegers found means to block up the mouth of the harbour with earth and sand, supported by trees driven in as piles; and when Carausius realised his position, he made his way by night through the camp of the enemy, and, going on board one of his own vessels, escaped to Britain, where his strength was greatest. He must have been much annoyed when he learnt that on the day after his escape a storm had destroyed the elaborate works of his foes, and that Boulogne harbour was once more open.

It has been already noted that Carausius had entered into treaties with certain Mediterranean rovers. These people were the descendants of the Franks who, under the Emperor Probus, had been sent as colonists to the shores of the Euxine to keep down the Scythians and other barbarians of those districts. The Franks, instead of withstanding the Scythians, in time made common cause with them against Rome, and, entering the Mediterranean, harassed it from end to end, burnt Syracuse, devastated the coasts of Spain and Africa, and terrified the Empire. In them Carausius recognised congenial spirits. It was arranged that the Frank pirates should come into the Atlantic, effect a junction with the British fleet, and fall upon the armada which Maximian had collected in the Rhine. Had the project been successful, Carausius might have become the most powerful prince of his day, and the whole Empire might possibly have been his.

But the piratical alliance found in Constantius a worthy opponent. Maximian, a man of very inferior capacity, had not been ready in time to take part in the operations against Boulogne; and Constantius, perhaps apprehensive of further delay, assumed the command of the thousand ships which were at length in a condition to sail, assembled and hastily built yet others, and, having stationed squadrons to observe Carausius and keep him in check, took the main body of his fleet towards the Straits of Gibraltar. Somewhere near the mouth of the Mediterranean, he met the Franks, and crushingly defeated them.[12] He then returned to Gaul in order to organise an expedition against Carausius in Britain. But while the preparations were still in progress, Carausius was treacherously assassinated by his friend and general, Allectus.

Constantius, with an inferior fleet, lay at the mouth of the Seine. Allectus assembled a superior one off the Isle of Wight, and, when all was ready, sailed with the intention of falling upon his enemy. But, by a strange coincidence, Constantius also sailed at about the same time; and it chanced that a fog came on in mid-channel. In the fog the fleets missed one another; and so fortune gave to Constantius an advantage which he could scarcely have gained for himself, seeing that Allectus was probably strong enough to have annihilated the Roman force had he encountered it. The influence of sea power was neutralised as it has seldom been before or since. Constantius, having thus accidentally got across the Channel unopposed, landed before Allectus could return, and burnt his ships, partly in order to inspire his people with the courage of despair, and partly, perhaps, because he realised that in an engagement at sea he was no match for the enemy, and that he must either win Britain or perish.

As soon as he suspected what had happened, Allectus also landed. His policy had alienated the people on shore, and though he was very strong at sea, he had but a comparatively feeble following on land. When, therefore, he fell in with one of Constantius' lieutenants, and attacked him with rash fury, he produced no impression, and, making a gallant fight, was killed. A further curious circumstance characterised the conclusion of this campaign, which had been so greatly affected by accidents. After the death of Allectus, his followers, chiefly seamen, seized London, and were upon the point of sacking it, when part of the Roman fleet, which had lost the main body in the fog, and had entered the Thames by chance, opportunely arrived on the scene, and landed a strong party which cut the pirates, many of whom were foreigners, to pieces.

In the decadence of the Western Empire, Lupicinus,[13] a lieutenant of Julian, repressed the piracies of the Scots; Theodosius, and Maximus, who was acclaimed Emperor by the army, did the same at a latter date, and repeatedly chastised the Saxon marauders at sea; and even under Honorius, Victorinus and Gallio were able to drive back the Scots, the Picts, and the Saxons, and to preserve some sort of order and security in the narrow seas. But towards the end of the period of Roman rule, the protection of the Roman fleets and armies was only occasionally and irregularly vouchsafed; and when at length the Britons, in reply to their prayers for assistance against the northern pirates, were told to defend themselves, they indignantly rose and drove out the last few official representatives of the effete Empire. For the moment the islanders were free; but they were totally defenceless, and the Picts pressed them sorely.

The Picts,[14] properly the Caledonii and Meatæ, were the tribes dwelling north of the Roman walls, and were probably Celts of Goidelic type. They were never subjugated by the Romans. The Scots were Ulster Gaels of predatory habits, who at the end of the fifth century colonised Argyle and established there a Scottish kingdom of Dalriada, which was for some time in alliance with the Irish Dalriada, whence the colonists had come. So much for strict definitions. But the Picts and Scots of the period immediately following the Roman abandonment of Britain, stand, in the language of early historians, for any of the freebooters who, coming from the north and west, harassed the southern and more civilised part of the main island. After the Roman withdrawal, they appear to have broken down the fortified walls which for many generations had limited their operations in the north; and, when the Britons attacked them in that quarter, the invaders seem, utilising their unchallenged sea power, to have landed an army in rear of the defence, and to have completely disheartened and confounded their opponents. But the period is one of turmoil, darkness, and myth.

Endeavours to unravel the confusing tangle of fact and fiction left us by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Nennius, Bede, Gildas, and the annalists, lead to the conclusion that, after the first period of chaos consequent upon the Roman desertion, one Vortigern, a prince of the Demetæ, by murder and fraud, acquired a leading position in the island; but that, finding himself opposed, on the one hand, by a considerable Roman party, under Ambrosius Aurelianus,[15] a prince of the Damnonii, and, on the other, by the Picts, and having little in view beyond his own personal welfare, he called in a roving band of Saxon pirates to assist him in supporting his threatened position. These pirates were under the brothers Hengest and Horsa,[16] said to have been sons of Wihtgils and great-great-grandsons of Wodan; and if it be true that they came with the ships only, and that nevertheless they were strong enough to effect the re-establishment of Vortigern's power in Britain, we are forced to believe that not only the British fighting capacity, but also the Pictish navy, must have been at a very low ebb in those days.

The brothers were probably younger sons, who, in accordance with the German custom of the time, were sent forth to seek their fortunes by any means which chanced to commend themselves to them. They were adventurers, and irresponsible. They landed at Ebbsfleet,[17] about the year 450, did Vortigern's work successfully, and, by way of reward, were permitted to establish themselves in Thanet. Ere long, they fell out with their old employer, one of whose sons, Vortimer, gained several successes over them, both afloat and ashore, and finally defeated them at Aylesford, where Horsa was killed.[18] But Vortimer soon afterwards died, the Britons found no leader to take his place, Saxon reinforcements came over, and the party of Hengest regained its ascendancy. Ambrosius Aurelianus is reported to have defeated and slain Hengest[19] himself; but Hengest left behind him a good leader in the person of his son Æsc, who, at length, achieved the complete conquest of Kent.

But the descent of Hengest and Horsa, important though it was in its consequences, was only the precursor of many other Saxon expeditions to Britain.

Ella,[20] with his three sons, Cymon, Whencing, and Cissa, and three ships, landed in 477 at a spot identified by Lappenberg with Keynor in Selsea, and, after a long struggle, obtained reinforcements and took and burnt the stronghold of Anderida, probably the modern Pevensey,[21] in 491. He established a Saxon kingdom in Sussex.

In 495, Cerdic,[22] with his son Cynric and five ships, landed, apparently in Hampshire, and, though at first he was not successful, obtaied at length the assistance of Æsc and Ella, and defeated the Britons. Like the other invading chiefs, he received reinforcements in course of time from the continent, and then, extending his operations, founded the kingdom of the West Saxons, and conquered the Isle of Wight as the result of a great victory at Whitgaresburh, now perhaps Carisbrooke. From this distinguished rover, all the sovereigns of England, except Canute, Hardicanute, Harold the Dane, Harold II., and William the Conqueror, can undoubtedly trace their descent; and Cerdic[23] himself is fabled to have been ninth in direct line from the god Wodan.

Thus the invasion of the Saxons, including the Angles and the Jutes, continued, by wave upon wave of healthy barbarians from Germany, until nearly all what is now England, and Scotland south of the Forth and Clyde, was covered by Saxon states. These fought among one another for the leadership. The tide of success ebbed and flowed, now one way and now another, until at length the only two important competitors for supremacy were the kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex.

For some time it seemed as if the struggle would terminate in favour of Mercia, especially during the reign of its great king Offa (757 to 796). Up to his day the Saxon princes in England, not being much troubled by foes from oversea, and having plenty of enemies inland, had paid little attention to the maintenance of that sea power whereby they had gained their new empire. But Offa looked without as well as within, and created a considerable navy, which found its justification in 787, when, for the first time, the Danes made an incursion with three ships "from Hæretha land,[24] and plundered part of Northumbria, and in 794,[25] when a monastery at the mouth of the Don was sacked. The Vikings did not fare well on either occasion. On the former, they were easily driven off with loss; on the latter, some of their vessels were wrecked. If Offa's successors had been as prudent as he was, and if internal dissensions had not opened the door to the enemy, these first efforts of the Danes might, perhaps, have been also their last for a long series of years. Unfortunately, the various Saxon kingdoms were still fighting among themselves, and, as for the Britons, they were glad to welcome the co-operation of any one, pirate or not, against their conquerors. They hated the Danes, but they hated the Saxons more; and when, not long after Offa's death, another Danish foraying party landed in Northumbria, it met with assistance from the dissatisfied Britons. Nor were the Danes effectively withstood again until the question of supremacy among the Saxon kingdoms had been finally decided by the victories of Wessex under Egbert.

But even Egbert, the wise monarch of a more or less consolidated England, was able to make the Danes respect him only in the last few years of his life, when all domestic enemies had been silenced. While he was still building up his power, the pirates sorely troubled the fringes of the country. In 800, the year of his accession to the throne of Wessex, bodies of Danes landed twice. One party pillaged the Isle of Portland, and the other ravaged the districts in the neighborhood of the Humber but was driven off by the country people. In 801 a body landed on Lindisfarne, and having defeated the Saxons there, re-embarked, proceeded round the south coast to Wales, and joined the Britons who were still unconquered in the part of the country lying to the west of Offa's Dyke. Egbert, however, met and beat them, yet not so badly as to deter them from making a fresh descent in 802, when heavily reinforced they entered the mouth of the Thames, seized Sheppey, and ravaged parts of Kent and Essex, up to within sight of the gates of London, where Egbert again met and beat them.

These forays were repeated, sometimes with more and sometimes with less success, nearly every year, and in 833 the crews of thirty-five Danish vessels inflicted a bloody defeat upon Egbert at Charmouth.[26] In 835, however, Egbert retaliated, coming up at Hengestesdun, now Hingston Down, with a combined horde of Danes and Cornish Britons, and nearly annihilating it.[27]

In the following year Egbert died. Under his successor Ethelwulf the same kind of thing continued. In 837 the Danes were defeated at Southampton,[28] but gained a success at Port in Dorsetshire. In 849, they defeated the king at Charmouth,[29] and in 851 worse befel. Athelstan,[30] a son of Egbert, assisted by the ealdorman Ealchere, seems to have fought a naval action with a Danish force off Sandwich, and to have defeated it, taking nine vessels; but another and much stronger Danish force, consisting of three hundred and fifty ships, arrived in the mouth of the Thames, landed an army, stormed both Canterbury and London, defeated an army headed by the King of Mercia, and was moving through Surrey, when it was encountered by Ethelwulf and his son Ethelbald, and routed with immense slaughter at Ockley.[31] Nevertheless, that year the Danes wintered for the first time in Thanet.[32]

It is noteworthy that of the numerous actions recorded as having been fought between the Saxons and the Danes thus far, one only, namely, that in which Athelstan was victorious off Sandwich, is clearly indicated as having been a sea-fight. From this it might be supposed that the Saxons had an inadequate navy; but by far the more probable explanation is, that they did not properly utilise such navy as they had. They seem, before the days of Alfred, to have thought more of guarding their coasts than of finding and defeating the enemy at sea; and as the usual policy of the Danes was to make a sudden raid, land a force, and allow it to shift for itself, and subsist upon the resources of the country until it could find opportunity to re-embark at another point, the Saxon tactics of stationing their vessels in or near the important ports may well have been very ineffective.

Ethelbert, who reigned from 860 to 866, was not more fortunate than his predecessors, and at one time his capital, Winchester, was attacked by his northern enemies. The reign, too, of Ethelred, from 866 to 871, was disastrous. The Danes made themselves masters of Northumbria and part of Mercia, seized Nottingham, completely conquered East Anglia, and advancing for the attack on Wessex, made Reading their headquarters. Led by Bagsecg and Halfdene, they fought no fewer than nine great battles in that neighbourhood in the course of the year 871, and were on several occasions successful; but King Ethelred and his brother Alfred beat them badly at Ashdown, near Didcot, and killed Halfdene. Ethelred, who seems to have been wounded there or in one of the subsequent and less successful fights at Basing and Merton, died soon afterwards, and Alfred, then probably in his twenty-ninth or thirtieth year, came to the imperilled crown.

Alfred's reign began badly. In the early summer of 871 he was defeated by the Danes at Wilton, and apparently so dispirited that he came to terms with the invaders, and offered them that which induced them to leave his part of the kingdom in the following year. But he secured this humiliating respite only to derive the greatest possible advantage from it. He at once devoted himself to naval matters, and in 875[33] he met seven Danish ships at sea, and scattered them, capturing one. Thereafter, for several years, he busied himself with the recovery of Wessex. In 882,[34] he was again afloat with a squadron, capturing four Danish ships after a very obstinate action. In 885, his vessels took sixteen Danish pirates[35] at the mouth of the Stour, but were afterwards themselves defeated by another Danish force. Until 893, however, Danish activity was less than it had been for many years previously, and Alfred had a considerable amount of leisure for attending to the improvement of the arts of peace.

Many of the Danes who had been driven from England by the energy of Alfred were, in the meanwhile, ravaging parts of the Low Countries and the north of France, under a leader of great ability named Hasting. Their continental successes tempted them to think again of England, and assembling at Boulogne, they built or procured a fleet of two hundred and fifty ships, embarked with their horses, and crossed the Channel to "Lemenemouth,"[36] where part of them landed. Some are of opinion that Lemenemouth was the mouth of the Rother. Be this as it may, the landed party stormed a fort and took up a position at Appledore, while Hasting, retaining with him eighty ships, proceeded to the mouth of the Thames, and landed at Milton,[37] where he formed a camp.

There is no record of what Alfred's fleet was doing at this period, but it does not appear to have met the enemy, and Hasting, in the next year, crossed the Thames into Essex, and fortified himself at South Benfleet, while two bodies of his friends co-operated with him, one, consisting of forty ships, going round by the north into the Bristol Channel and landing a force on the north coast of Devonshire, and the other, of one hundred ships, going down Channel, and landing a force for the siege of Exeter. Alfred divided his army into two parts, sending one against Hasting at Benfleet, and himself leading the other against his enemies in the west. Hasting was driven from Benfleet, and his fleet was part taken and part destroyed, but he fell back on South Shoebury, and was there joined by ships from East Anglia and Northumbria. In the west the appearance of Alfred caused the invaders to raise the siege of Exeter and re-embark, but going eastward, they landed again and attacked Chichester. There they were driven off, with the loss of a few ships.[38] Hasting made further unsuccessful efforts to push his fortunes in England, and struggled on until the summer of 897; but he then gave up the task as hopeless, and disbanded his remaining forces.

It was in 897 apparently, that the ships of the new and improved type[39] designed by Alfred were first tried in action. Six Danish vessels were ravaging the coasts of Devonshire and of the Isle of Wight, and the King ordered out against them nine of his novel craft, manning them partly with English and partly with Frisians, who were reputed the best seamen of that time. The Danes were found, three afloat and three aground. The three which were in a condition to move immediately issued from their haven, and fought very gallantly, two, however, being captured and their crews put to death, in accordance with the King's principle for dealing with such freebooters. The third escaped, with but five men remaining on board. Going into the haven to attack the other vessels, the royal ships all managed to run aground, too, three lying close to the three stranded Danes, and the rest at some distance on the other side of the harbour. When the tide had run out, the Danes furiously attacked the Saxon ships near them, killing seventy-two of their people, but themselves losing as many as one hundred and twenty. At length the tide rose again, and it would have enabled the English on the other side of the haven to intervene with decisive effect, but for the fact that it floated the Danes first. They plied their oars, and escaped from the immediate danger, but so badly damaged were they, that two of them went ashore elsewhere and were captured, and their crews, being conducted to Winchester, were there hanged by the King's command.[40]

Having been, as is supposed, the first English sovereign to command a squadron in action at sea, Alfred has been called the first English admiral. There is, perhaps, danger of overrating the importance of his exploits afloat. He won no decisive victory there; and it is easy to form an exaggerated estimate of the efficiency to which the fleet attained under him, and of the material improvements which he introduced. But it stands to his credit that he appreciated the value of offensive defence, and was one of the first Englishmen to employ it.

Under Edward the Elder (901-925), the son and successor of Alfred, but two notable naval events took place, although during most of the reign the Danes were troublesome, both on the coasts and inland. In 904, Ethelwald, a son of Ethelred, having put forward his claim to the crown, obtained Danish assistance from Northumbria, and, with as many ships as he was able to collect, effected a descent in Essex,[41] subdued it and persuaded the East Anglian Danes to invade Mercia; but he was killed in a skirmish in the course of the following year. In 915 or, according to others, in 918, a large piratical fleet from Brittany[42] fell upon the coasts of Wales and carried off the Bishop of Llandaff, who was subsequently ransomed by Edward for forty pounds.

Athelstan (925-941), Edward's son, took more interest than most of his predecessors in foreign politics, and had a share[43] in the restoration of Louis d'Outremer, son of Charles the Simple, to the throne of France. In 933 he invaded Scotland,[44] both by sea and land; but his great exploit was the crushing, in 937, of the formidable alliance arrayed against him by Constantine, King of Scots, Olaf (or Anlaff) son of Guthfrith, Danish king of Northumbria, Olaf (or Anlaff), Cuaran, the Danish king of Dublin, and several British princes, including Owen of Cumberland. This combination was arranged in retaliation for Athelstan's action against Scotland, and especially for the manner in which his fleet had ravaged the coasts of Caithness. The campaign, which seems to have been to a considerable extent a naval one, was decided by the victory of Brunanburh, where Athelstan routed all his opponents. A translation of the Saxon war song, composed in honour of the event, will be found in Freeman's 'Old-English History.'

The site of Brunanburh is undetermined. Some place it in the Lothians, some in Northumberland, some in Yorkshire and others at Brumby, in Lincolnshire. Simeon of Durham[45] makes Olaf Guthfrithsson's fleet, without the fleets of his allies, to have consisted, on the occasion of this descent, of no fewer than 615 vessels; so that Athelstan's power must have been, indeed, enormous.Edmund the Elder (941-946), Edred (946-955) and Edwy (955-959), seem to have been capable monarchs, although the character of the last, owing to his attitude on matters of ecclesiastical policy, is bitterly attacked by contemporary monkish historians. They held their own against the Danes who were already established in the island; but there are no records of their having had to cope with serious Danish irruptions from over sea.

Edgar (959-975), like his immediate predecessors, was little troubled from abroad, and utilised the comparative peacefulness of his reign in organising his navy. It is related that he divided his fleet into three permanent squadrons of equal force, stationing one in the North Sea, a second in the Irish Channel, and the third on the north coasts of Scotland; and that every year, after Easter, he made a tour of inspection round his realms by sea, joining the North Sea Squadron first, cruising with it from the mouth of the Thames to the Land's End, and there dismissing it to its station, and joining the Irish Channel Squadron. With this he cruised as far as the Hebrides, where he met the Northern Squadron and, joining it, was conveyed by it round the north of Scotland and back to the mouth of the Thames.[46] In these annual evolutionary cruises he visited all the ports and estuaries, made provision for the security of the coasts, and occasionally attacked his enemies.

In the course of one expedition he is said to have reduced the Irish Danes, and to have taken Dublin. In the course of another, in 973, he is said to have been met at Chester by the kings, Kenneth of Scots, Malcolm of Cumbria, Maccus of Man, Dunwallon of Strathclyde, Inchill of Westmoreland, and Siferth, Iago, and Howell of Wales, who, in token of subjection to him, manned his barge and, Edgar steering, rowed him on the River Dee.[47]

But it must be remembered that Edger, unlike Edwy, was on excellent terms with Dunstan and the ecclesiastical party, and that the ecclesiastics were practically the sole historians of those times; and it my be regarded as certain that Edgar's naval glory, which was no doubt considerable, was, if anything, rather exaggerated than minimised by the chroniclers. Ethelward, one of the few contemporary writers who possibly was not an ecclesiastic, and who, according to his own account, was nearly related to the royal house, drops hints that, after all, Edwy may not have been inferior as a monarch to Edgar. Be this as it may, the monkish estimate of Edgar as one of the greatest of British naval reformers has received general acceptance; and, with very few intervals, there has, in consequence, always been a large British man-of-war bearing the king's name since the day in 1668, when it was conferred upon a two-decker at the instance of James, Duke of York, Lord High Admiral, who had previously given the name to one of his sons who died in infancy.

The brief reign of the boy Edward, miscalled The Martyr, (975-979), was uneventful; but the latter part of the reign of his half-brother, Ethelred the Purposeless (979-1016), was full of naval incident; and, indeed, even the earlier part, from its very beginning, witnessed a marked revival of Danish aggression from across the North Sea. Not however, until 988 did the Danes renew their attempts to settle in the country. Up to that date their expeditions were merely raids and forays.

It was in 988 that Olaf Tryggvesson, one of the most formidable, bloody and revengeful of the Vikings, harassed Watchet and killed Gova, the Thane of Devon. Olaf was the son of a Norwegian sea king, but may have been born in Britain. In 991 he led a fleet of 450 ships to Stone, thence to Sandwich, and thence to Ipswich, and, pressing as far as Maldon, there defeated and slew the earldorman Brihtnoth, who had been sent against him. Ethelred made some attempts to assemble a fleet, so as to cut off the enemy, but his plans were betrayed by the earldorman Elfric, and only a very partial success by sea was secured. In 994 Olaf allied himself with Sweyn[48] of Denmark, son of Harold Blaatand, and the two, with ninety-four ships, made an abortive attempt on London.[49] Driven thence by the townsmen they devastated Kent, Sussex and Hampshire, both along the coast and for some distance inland; and on an evil day Ethelred agreed to buy them off by payment of £16,000 and the provision for them of food and winter quarters at Southampton, Olaf promising never again to visit England, unless peacefully.[50] In the spring he departed for Norway, which he wrested from Earl Hacon and ruled for several years; but, though he personally kept his word, his promise bound no one save himself, and the Vikings presently began their incursions anew.

In 997[51] a Danish fleet entered the Tamar, went up to Lidford, crossed to Tavistock, burned the church there, and carried off an immense amount of booty. In 998 the Danes ravaged Dorsetshire and Hampshire; and though English armies were sent against them, the pirates were invariably victorious. In 999 they sailed up the Medway, disembarked at Rochester, defeated the local forces, and ravaged West Kent. Ethelred collected a fleet as well as an army; but the latter did no good to his cause, and the former, owing to delay on the part of the leaders, was not ready until too late.[52] It is probable that this expedition, like several previous descents, was bought off, and that the refusal of Malcolm of Cumbria to contribute money for the purpose was the cause of the hostilities which Ethelred waged against him with success in the following year.

But a nearly contemporaneous descent upon Normandy, whither some of the Danes had retired, was a failure; nor is this to be wondered at. It is tolerably clear that Ethelred's naval forces were no longer in hand, and were in fact in a state bordering upon mutiny. A fleet destined to support the king on his Cumbrian expedition, instead of accompanying him, had gone away on its own account and ravaged Maenige, which some take to have been Man and others Anglesey.[53]

In 1001 the Danes reappeared, this time at Exmouth, where they were joined by a foreigner named Pallig, who had received favours from Ethelred, and had sworn fealty to him. Great havoc was wrought in Devon and Somerset, and, the forces of the realm having failed to eject the pirates, a humiliating bribe of £24,000 was given them to induce them to depart in the following year.[54]

Then it was that Ethelred bethought himself of getting rid of the bloodsuckers who were preying upon his ever weakening inheritance by murdering all the Danes resident in England. The crime, or as much of it as was possible, was perpetrated on St. Brice's Day, November 13th, 1002,[55] and in the massacre a sister of Sweyn, Prince of Denmark, who had banded himself with Olaf in 994, perished. This circumstance seems to have sealed the fate of England. The massacre thinned out the Danes who lived in what had in earlier times been the Danelagh, and who had for generations fitted out piratical expeditions against the rest of the country and provided bases of operations for their kinsmen foraying hither from Denmark; but, on the other hand, it exasperated the Danes at home, and especially Sweyn, to madness.

Sweyn's immediate reply was a descent, in the course of which he stormed Exeter and captured Salisbury,[56] and, in fact, met with little resistance, except in East Anglia. This was in 1003. In 1004, after having drawn off for the winter, he returned, sailing up the Yare to Norwich. While some of his lieutenants amused the people by pretending to treat with them, he advanced surreptitiously to Theford. Ulfcytel, Ethelred's officer at Norwich, ordered the Danish ships to be destroyed; but his directions were not attended to. He himself, with a force of men, followed Sweyn, and met him on his way back. A fierce battle resulted, but Ulfcytel was killed, and the Danes were able to re-embark. In 1006 they came again, in greater strength than ever, capturing and sacking Sandwich. Ethelred bought them off with provisions and £36,000 in money.[57] Then he made tardy efforts to reorganise a fleet,[58] and in 1008 levied for the purpose a tax which, says Nicolas,[59] "is considered the first impost of the kind and the earliest precedent of ship-money." Great numbers of vessels were built, some authorities say 800; and probably about 30,000 men were armed for service; and in 1009 the fleet was ordered to make rendezvous at Sandwich. But treachery, mismanagement and misfortune brought the armada to nought.

A man named Wulfnoth, a South Saxon, head of a family which subsequently made a great naval reputation for itself, and father of Earl Godwin, then a young man in his teens, induced twenty of Ethelred's ships to follow him, and carried them away, probably with the design of turning pirate. Brihtric was despatched in pursuit of him with eighty vessels; but this squadron fell in with a violent gale of wind and, being dispersed, was turned upon in its distress by Wulfnoth, who burnt every one of the ships. When the news reached the rendezvous a panic seized everyone there, the king and nobility fled to London, and the squadron was either abandoned or scattered.

The Danes took instant advantage of the confusion. Thurcytel[60] the Tall, leader of a piratical community which had for some time been established at Iona, and which had just been broken up, had an understanding with Sweyn, and arrived with fifty ships at Greenwich. He plundered great part of the south of England, extorted heavy sums by way of ransom, captured Canterbury, thanks to the treachery of Elfinar, sacked that city, and murdered Archbishop Alphege at a drunken orgie on Easter Saturday, 1012. Meanwhile London was ineffectually attacked,[61] and Oxford was burnt. Ethelred could do nothing. He was tired of buying off invaders. He hired Thurcytel, and forty-five of his ships,[62] to assist in the protection of the kingdom. Sweyn came once more, in 1013, accompanied by his son Canute, and landed at Sandwich. Thence he went to the mouth of the Humber, and thence along the Trent as far as Gainsborough. Northern England submitted to him; and when he had horsed his army he marched southward, leaving his prisoners and his ships under the care of Canute. London was attacked, but Thurcytel contributed to the defence; and Ethelred was able to repulse the Danes,[63] who thereupon turned their attention to the reduction of the West of England, which quickly acknowledged Sweyn as king. This defection decided the wretched Ethelred to abandon his country. Once more Thurcytel proved useful, for they were his ships that escorted the unfortunate monarch to Normandy; but Thurcytel's fidelity was only hired, and, three years later, the soldier of fortune was fighting for Sweyn's son Canute against Ethelred's son Edmund Ironside. He died Regent of Denmark.

Canute succeeded his father in 1014.[64] At the news of the old king's death Ethelred returned, with Edmund Ironside, and was acclaimed by the Saxon portion of the people, who declared "that no lord was dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would rule them rightlier than he had before done." Ethelred made promises freely, and entered into a kind of compact with his subjects, the first of the kind on record in English history. One of the first things he did, however, was to levy £21,000 for the army,[65] with which he marched against Canute, who was at Lindsey, and who retired in his ships to Sandwich, where, after mutilating them by cutting off their hands, ears, and noses, he landed the hostages who had been entrusted to his father Sweyn. With Sandwich[66] as his base, Canute ravaged Kent, Somerset, Dorset, and Wiltshire; later, he laid waste Mercia and Northumbria, and subdued them; but while he was still preparing for the final reconquest of Wessex, his rival Ethelred died on April 23rd, 1016.

Edmund Ironside was chosen king by the citizens of London, who were at that moment threatened by the presence of Canute in the Thames. Canute had been reinforced by the desertion from Edmund of Edric Streona, one of Ethelred's oldest, most trusted, and most deceitful advisers, with forty ships.[67] Edric subsequently deserted back to Edmund, and again, at the battle of Assandun, back to Canute—all within a year. Edmund was in the west when in May or June Canute's fleet approached London; and the invaders were able, by digging a canal round the south side of the city, so to station their vessels that they could act both above and below bridge. The place was held by the inhabitants, but it was closely blockaded by water and invested by land, until Edmund, after much fighting, returned, and obliged the Danes to raise the siege and retire down the river. Various successes[68] were gained by each side until towards the close of 1016, when the Danes won so conclusive a victory at Assandun, supposed to be Aslington in Essex, that the Saxon Witan itself proposed the division of the country between the rivals. This solution had scarcely been agreed to ere Edmund died, after a reign of only seven months, and Canute became sole monarch of England.

The naval exploits of Canute after 1016 scarcely belong to English history, for although this great king spent most of his time in this country, and reckoned it the chief of his numerous possessions, England was at peace during most of his reign. Nicolas[69] thus summarises from the Saxon Chronicle his goings and comings: "In 1018 he sent part of his forces back to Denmark; but he retained forty ships until the following year, when he went with them to that kingdom. Canute returned to England early in 1020, and in 1022 he is said to have accompanied his fleet to the Isle of Wight; but, as in 1023, he is stated to have 'come again to England,' it would seem that he had made a more distant voyage, probably to Denmark. In 1025 Canute again visited Denmark with his ships, and being attacked at the Holm by a Swedish fleet and army, after a sanguinary conflict the Swedes remained in possession of the field. His return to England is not noticed; but in 1028 he went from England 'with fifty ships of English thanes' to Norway, and having driven King Olaf out of the country, took possession of his dominions."

In one sense, therefore, we may reckon Norway as England's first foreign conquest, in that it was made, partially at least, by Englishmen, though for the Danish rather than for the English crown. In another direction also the country made a new departure under Canute, who established the Huscarls, a permanent force of fighting men governed under a military code. They were either 3000 or 6000 in number, and constituted the earliest approach to a standing army in England. The invasion of Scotland in 1031 was a naval as well as a military expedition, but few details of it have been handed down to us; and after it, until Canute's death at Shaftesbury in November, 1035, there was peace.

Upon Canute's death, his son by Emma,[70] widow of King Ethelred, seized Denmark, while his reputed son by Elgiva of Northampton was generally supported in England, though not by the West Saxons nor by Godwin, who was already powerful. In consequence, the former, Hardicanute, became for a time King of Denmark and Wessex, and the latter, Harold I., King of England north of the Thames. An attempt in 1036 by two of Ethelred's sons to recover their father's kingdom failed, and was bloodily punished by Harold; and in the following year the people, becoming disgusted with Hardicanute's long absence abroad, forsook him, and gave in their general adhesion to Harold, who thus reunited the kingdom into a whole, which has never since been split up. Emma was banished to Flanders; but Harold prudently reconciled himself with Godwin, who had put himself at the head of a respectable English party. Hardicanute was little inclined to submit to this arrangement, and in 1039 joined his mother at Bruges, and began preparations for an invasion of England. But before he could carry out his plans Harold died, on March 17th, 1040.

Hardicanute at once crossed the Channel, arriving at Sandwich before midsummer with sixty ships, for the support of the crews of which he levied a tax at the heavy rate of eight marks per rower. This and his large subsequent levies of Heregeld, as well as his severities, gained him much unpopularity; and in the hope of bettering his position in the minds of the people, he sent over to Normandy for his half-brother Edward, son of Emma by Ethelred, and installed him at court as heir to the throne. Accordingly, when Hardicanute died in June, 1042, Edward, later known as the Confessor, succeeded without serious opposition.

There were not wanting other pretenders to the crown. One was Sweyn Estrithson, a nephew of Canute; but Godwin was on the side of Edward, and Godwin was the most powerful man in the country. Magnus, King of Norway and Denmark, also put forward claims, and would have endeavoured to enforce them in 1045, had his attention not been distracted by the attack upon him of Harold Hardrada and Sweyn, his rivals at home.[71] Meanwhile Emma, who still coquetted with the Danish party, and who seems to have preferred her connections by her second to those by her first marriage, was disgraced; and later, several of the more dangerous Danish lords in England were banished as a measure of precaution. Thus Edward's position was made secure. But Edward had been educated at the Norman court, and had Norman sympathies and Norman favourites. Danish influence gave place, not, as should have been the case, to English, but to Norman; and there was much English discontent.

A man to lead the national party was happily at hand in the person of Godwin, Earl of the West Saxons, the strongest, most wealthy, and most able subject of his day, and a very distinguished seaman. He seems to have successively misunderstood the tendencies both of Emma and of Edward. He certainly rendered valuable assistance to the plans of each, vastly, it is true, increasing his own importance and social dignity in the process. He had married Gytha, a niece of Canute; his daughter Edith married Edward the Confessor; his sons and nephews were all advanced to high posts. But at length he aroused himself to the growing seriousness of the foreign aggressions, and took up a definite position in the van of the national movement. Godwin forced upon the English monarchy almost the first of the long series of constitutional compromises which have given us our liberties. He may have been a selfseeker; undoubtedly he was, in some stages of his career, very much like a pirate. But he initiated a good work. When foreign influence, grown to an unexampled height, at length procured the outlawry of him and his family, he retired to Flanders, to reappear at the head of a fleet. He was beloved and admired by the people, and Edward, the most overrated of the English kings, was supported only by the clergy and the foreigners. Opposition was hopeless; the king's forces refused to fight against the English hero, and Edward had to give way on nearly all points, and to get rid of the more objectionable of his Norman advisers and sycophants. Here the sea helped in the striking of a heavy blow for the cause of freedom: and although Godwin survived his triumph for only a year, he died victor in a great constitutional struggle.

But the naval events of the reign must be noted in their order. Godwin's victory came late.

The fleet seems to have been cared for throughout. In 1044 Edward was at Sandwich with thirty-five ships, and in 1045, when the invasion of Magnus was expected, as large a fleet as had ever been seen in England was collected at the same port. Edward was asked by Sweyn to assist him with a squadron of fifty vessels against Magnus, but the request was refused.[72] Magnus's navy being reputed to be exceedingly powerful, and popular opinion being apparently doubtful whether that of England would be justified in going far from its own coasts to intervene in a foreign quarrel. Nor was the refusal unwise, for there was plenty for the fleet to do at home. Not long afterwards Sandwich itself was attacked by the pirates Lothing and Yrling,[73] with twenty-five ships, and a large amount of booty was carried away. Thanet also was attacked, but drove off its assailants. Essex fared less fortunately, and was ravaged, the pirates taking their spoils to Flanders and there selling them. The king was at sea during this time, but did not succeed in falling in with the freebooters.

Baldwin, Count of Flanders, had protected the operations of these and other sea-robbers, and consequently, when, in 1049, Baldwin was at war with the emperor, and the latter invited Edward to assist in blockading the territories of the Count, the King of England was disposed to comply, and once more collected his fleet at Sandwich.[74] But he appears to have had no time to put to sea with it ere Baldwin and the emperor came to terms, and then, deeming that so large a force was unnecessary, Edward sent his Mercian contingent home.

The rest of the fleet he designed to utilise for another object. Osgod Clapa, a Dane who had been in Edward's service, but who had been banished in 1046 for suspected complicity in the machinations of Magnus, had taken to piracy, and was reported to be at Ulp with thirty-nine ships; whereupon Edward dispatched part of his force in chase of the rover, who ran for Flanders with six ships only, leaving the rest to plunder Essex; and as the English force seems to have been completely deceived and to have pursued Osgod, the plunderers did their work almost unmolested, and re-embarked in safety.[75] Thus the great armament at Sandwich did little good.

While the king was still at Sandwich, Godwin's eldest son Sweyn, who, in consequence of having been refused permission to marry the Abbess of Leominster, whom he had abducted, had thrown up his earldom and retired in a huff to Denmark, decided to endeavour to make his peace with Edward, and arrived with seven ships at Bosham for that purpose. Upon his appearance off the English coasts he was apparently treated as an enemy, for the men of Hastings took two of his vessels and brought them to the king after having killed their crews.[76] During his absence his earldom had been divided between his brother Harold and his cousin Beorn. Both Harold and Beorn were consequently opposed to the return of Sweyn, and directed him to put to sea again, giving him four days wherein to do so. This, no doubt, incensed Sweyn. Soon afterwards an English squadron, consisting of two "king's ships" and forty-two "people's ships," under Godwin, and another of his sons, Tostig, with, apparently, Beorn on board, was driven by stress of weather into Pevensey while in pursuit of pirates. Sweyn went thither, and begged Beorn to accompany him to Sandwich and to intercede for him with the king. Beorn agreed, and seems to have started in a vessel of his own, or overland. But Sweyn presently seized him, and took him by boat to his own vessel, which proceeded to Dartmouth, where Sweyn murdered his cousin and buried his body in the church. It was subsequently removed to Winchester, and interred near that of Canute; and Sweyn[77] escaped to Flanders, to be pardoned in 1050, and restored to all his possessions by Edward.

Another naval event of 1049 was the arrival of thirty-six ships from Ireland to assist Griffith of Wales. Towards the end of the year Edward "discharged nine ships from pay, and they went away, ships and all; and five ships remained behind, and the king promised them twelve months' pay."[78]

At this time matters were rapidly coming to a head between Godwin and Edward. In 1051 the king, contrary to the desire of the earl and of the monks of Canterbury, saw fit to advance to the Archbishopric a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, who had previously been for six years Bishop of London. Another Norman had been made Bishop of Dorchester, and the English party was greatly annoyed. It was then that Godwin was ordered to Dover to punish the townsmen for their behaviour to some piratical followers of Baldwin of Flanders. Godwin declined to do this unless the men were first given a fair trial. It was then also that complaints were made by the people of Sweyn's earldom of Hereford that some Normans or French had established themselves there, and were illtreating the country folk.

Godwin and his family seem to have thought that the moment had come for stern resistance to Edward's unreasonable preference of foreigners. Sweyn and Harold, and even Tostig, who had lately married a sister of Baldwin, were of one mind. The Witan at Gloucester summoned Godwin to attend before it. The earl replied by collecting his friends at Beverstone, near Malmesbury. The Witan removed to London, and outlawed Sweyn, but contented itself with again summoning the earl and Harold, to whom, however, safe conduct and hostages were refused; so that their only course was flight.

Godwin and Sweyn went to Bosham, embarked thence for Flanders, and stayed abroad during the winter.[79] Harold embarked at Bristol for Ireland. Sweyn, recollecting the abducted abbess and the murder of Beorn, departed on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and died while on his way back; but early in 1052 the other members of the exiled family began active operations with a view to return.

Harold, with a squadron, appeared off the mouth of the Severn, sacked some places in Somersetshire and Devonshire, and killed a number of people, including "more than thirty good thanes." The threat of an invasion from Flanders by Godwin prevented interference; for forty ships[80] of Edward's fleet, probably nearly all the vessels then in commission, lay at Sandwich under the Earls Ralf and Odda, or cruised in the offing, on the look-out for the enemy. Godwin evaded them and landed at Romney, where, in his own territories, his popularity raised him a large force, all the "butsecarls," or boatmen, of Hastings and the neighbouring ports joining him enthusiastically. It is less than forty miles by sea from Sandwich to Romney Bay, but the king's ships did not succeed in getting to the latter place in time to prevent the earl from sailing thence to the westward. Ralf and Odda returned to Sandwich, and went thence to London, where it is not astonishing that they were superseded. As for Godwin, he went no farther west than the Isle of Wight, and was there joined by Harold, with nine ships from Ireland. The combined force returned up Channel, picking up more butsecarls at Romney and Folkestone, and reached Sandwich "with an overflowing army."[81] The royal fleet had quitted Sandwich, and Godwin pressed on for the Thames. He mounted as far as Southwark, found the people there well disposed towards him, entered into an understanding with them, landed some troops, and advanced cautiously through the south arch of London Bridge. The royal fleet, increased to fifty ships, seems to have lain somewhere below the spot where now stands St. Paul's; and Godwin was upon the point of attacking it, when, happily, an arrangement was come to, and bloodshed was prevented.[82]

Thus Godwin triumphed. His victory led to the outlawry of Robert of Jumieges, Bishop Ulf, and other Norman place-holders, who escaped with considerable difficulty to Normandy; and English influences became predominant at court. But in the following year the great earl died. He had, however, a worthy successor as chief of the party of England for the English, in the person of his eldest surviving son, Harold, a true West Saxon, yet also, on his mother's side, a grand-nephew of Canute. Harold, while his brother-in-law, Edward the Confessor, lived, was a strong and patriotic mayor of the palace to a roi fainéant, and at first he was zealously supported by all the members of his house, including his brothers Tostig, Earl of Northumbria, Gyrth, Earl of East Anglia, and Leofwin, who held sway in Kent, Essex, and adjoining counties. The two last, indeed, remained faithful to their kinsman to the death.

In 1062, Griffith of Wales once more became troublesome; and Harold and Tostig combined to repress him. The campaign was chiefly military; but its issue was much influenced by the billiant naval success of Harold, in 1063, at Rudeland, where the Welsh fleet was destroyed. Griffith was assassinated by one of his own followers, and both his head and the prow of his ship were sent as trophies to Edward.[83] Then came the defection of Tostig, in some sense the gloomiest actor in the events which were fast crowding upon England. He had governed ill in Northumbria, and his people revolted, deposed him, and set up Morkere in his stead. Edward, advised by Harold, admitted the demands of the insurgents, recognised Morkere, and banished Tostig, who retired to nurse schemes of revenge at Bruges. Morkere, it should be said in explanation, was brother of Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and of Aldgyth, wife of Harold, and widow of Griffith of Wales; so that the transfer of power in Northumbria did not necessarily reduce the predominance of the family interests of the House of Godwin.

On January 6th, 1066, the Confessor died, after bequeathing his kingdom to Harold. The old king left no children of his own, and although there was a nearer heir in the person of Edgar Atheling,

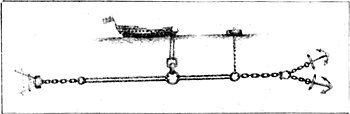

SHIP OF HAROLD'S FLEET.

(From the Bayeux Tapestry.)

grandson of Edmund Ironside, and although he had a certain following, he was but a child of eight, and, of course, was not in a position either to press his claims or to mount the throne in those turbulent times. Indeed, it seems to have been so clearly recognised, even by his friends, that the burden of the crown would have been too heavy for the boy, that no serious efforts were made to secure it for him. On the other hand, Harold was strong, vigorous, popular, and in the prime of life. The only serious cloud upon his prospects was one which Harold, who was best aware of its existence, did not regard as threatening. It had been his misfortune, years earlier, to be wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu, and to be handed over by the noble upon whose territory he was cast, to William, Duke of Normandy, who had exacted as price of release a sworn promise that Harold would support William's claim to the inheritance of Edward. Harold either looked upon the whole affair as grim jest, or considered that no promise made under duress was binding upon him; and, when Edward died, took the crown, apparently with confidence.

He underrated William's ambition and pertinacity. But before the moment came for him to reckon with his most dangerous enemy, he had to deal with his troublesome brother Tostig, who, upon learning of Harold's accession, appeared with fleet off the Isle of Wight, and levied money and provisions. Tostig's offer to co-operate with William was rejected; and, quitting the south coast, the outlaw went, with sixty ships, to the Humber, whence, however, he was driven by Edwin of Mercia. Never very popular, he was thereupon forsaken by most of his followers, and proceeded with only twelve vessels to Scotland. Harold Hardrada of Norway, also at that time cherished vague designs against England, and was at the Orkneys with a large force. The king and the outlaw met, and agreed to work together. They sailed to the Humber, landed, defeated Edwin and Morkere at Fulford, and seized York; but King Harold of England, the most energetic leader of his age, marched rapidly north, and on the 25th of September, 1066, fell upon the invaders at Stamford Bridge,[84] on the Derwent, and gained bloody, but concrete victory, Harold himself being wounded, but Harold Hardrada and Tostig being slain. The pursuit was hot, and comparatively few of the enemy gained their ships, many of which were burnt.

- ↑ 'De Bell. Gall.' iii. 14.

- ↑ The account fellows Cæsar: 'De Bell. Gall.,' iv. v.

- ↑ According to D'Anville; but some identify it with Calais, some with Boulogne, and some with Ambleteuse.

- ↑ For discussion of this subject, see 'Archæologia,' xxi. 501.

- ↑ 'De Bell. Gall.,' v. 8.

- ↑ 'De Bell. Gall.,' v. 11.

- ↑ Hor. 'Carm.' i. 35; iii. 5.

- ↑ Sueton. in Calig. 44.

- ↑ Tacit. in Agric.; Juven., Sat. II.

- ↑ Coote's 'Romans in Britain'; Rhys's 'Celtic Britain'; Guest's 'Origines Celticæ.'

- ↑ 'Scotichron.' ii. 38; Stukeley's 'Medallic Hist. of Carausius.'

- ↑ Eutrop. ix.; Bede, i. 6; Aurel. Vict. 39, etc., give 'History of Carausius and Allectus.' See also Speed's Chronicle.

- ↑ Bede, i. 1; Amm. Marcel. xx.

- ↑ Skene's 'Celtic Scotland'; Rhys's 'Celtic Britain.'

- ↑ Gildas, 25; Bede's 'Eccles. Hist.,' i. 16.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., anno 449; Green's 'Making of England.'

- ↑ With three "long ships," otherwise "ceols" (keels). Sax. Chron., 298.

- ↑ In 455. Close to Aylesford, in Kent is Kit's Coty House, a cromlech, said to commemorate one Catigern, who also fell.

- ↑ In 489 (?).

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 300.

- ↑ But Camden says Newenden, Kent; others think near Eastbourne.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 300.

- ↑ He died about 534.

- ↑ Ingram says "the land of robbers."

- ↑ Simeon of Durham, 112; Sax. Chron., 338.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 344.

- ↑ Ib., 344.

- ↑ Ib., 345.

- ↑ Ib., 346.

- ↑ He held sway over the South Saxons.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 346.

- ↑ Ib., 345.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 355.

- ↑ Ib., 358.

- ↑ Ib., 359.

- ↑ Difficult to identify. See Southey's ed. of 'Lives of Admirals,' i. 35.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 363, 364.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 364-369.

- ↑ Ib., 371. See ante, Chap. I. p. 13.

- ↑ Ib., 370, 371.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 372.

- ↑ Ib., 377.

- ↑ Flodoard, quoted by Daniel, ii. 647.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 383-385.

- ↑ p. 25.

- ↑ Matt. of West.

- ↑ Will. of Malmesbury, i. 236 (ed. Hardy); Flor. of Worc., 578 (ed. Petrie); Hoveden, 244, etc.; but the names of the kings are variously given. See also 'Libel of English Policie.'

- ↑ More properly Swegen.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 402.

- ↑ Ib., 402, 403.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 406.

- ↑ Ib., 407.

- ↑ Ib., 407.

- ↑ Ib., 408, 409.

- ↑ Ib.

- ↑ Sax. Chon., 410, 411.

- ↑ Ib., 412, 413.

- ↑ Ib., 413.

- ↑ Nicolas, 'Hist. of Roy. Nav.,' i. 43.

- ↑ Or Thurkel.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 414.

- ↑ Ib., 418.

- ↑ Ib., 418, 419.

- ↑ Ib., 420.

- ↑ Ib., 420, 421.

- ↑ Later, on his safe return from a pilgrimage to Rome, Canute gave the port of Sandwich, and the dues arising from it, to Christ Church, Canterbury.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 422.

- ↑ Ib., 422-424.

- ↑ Nicolas, i. 48; from Sax. Chron., 426-429.

- ↑ Also known as Edith.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 435.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 437, 438.

- ↑ Ib., 438.

- ↑ Ib., 438, 439.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 440.

- ↑ Ib., 441.

- ↑ Ib., 440, 441.

- ↑ Ib., 441, 442.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 444.

- ↑ Ingram has "smacks."

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 446-448.

- ↑ Ib., 448, 449.

- ↑ Ib., 458.

- ↑ Sax. Chron., 462-465.