The Severn Tunnel/Chapter 7

CHAPTER VII.

A YEAR OF GOOD PROGRESS [1882].

Progress of the work—1882.On the 2nd November, 1881, I received orders from Sir John Hawkshaw to go on with the whole of the works as rapidly as possible. The contract had contemplated that for the first eighteen months only the work under the ‘Shoots’ should be proceeded with; but it took as nearly as possible twelve months from the date of signing the contract to clear the works of water. Twelve months more had been used in completing the heading under the river, securing the old shafts, sinking new ones, and commencing the brickwork under the ‘Shoots’ and under the Salmon Pool; but sufficient had been done to inspire confidence, and the order was therefore given to proceed with the whole of the works at once. I therefore purchased, at the end of December, an additional 4½ acres of land for various purposes, and leased a further quantity of 3½ acres for building additional houses.

At the end of the year 1881 about 60 yards of the full-sized tunnel had been completed at the bottom Progress of the work—1882. of the Sea-Wall Shaft, and about 300 yards of continuous arching had been turned westwards of the shaft.

In addition to this the arching had been commenced at two break-ups going westward, the long heading had been joined, and ventilation was established through the works between the Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire sides of the river. Four break-ups had been started in the Pennant rock under the ‘Shoots,’ and about 100 yards of arching had been completed from these four break-ups. The 9-ft. barrel had been entirely lined with brickwork, and the 18-ft. tunnel at the bottom of the new shaft at Sudbrook had also been completed with a bellmouth into it, out of the 9 ft.

A head-wall had been built across the entrance to the Iron Pit, and a 3-ft. sluice-valve fixed in it, from which rods were led up the New Pit to the surface of the ground.

About 60 yards of tunnel had been completed at the bottom of the New Pit, and both the New Pit and the Old Pit at Sudbrook had been secured by brickwork to the arch of the tunnel.

At 5 miles 4 chains both shafts had been bricked, and about 15 yards of tunnel completed at the bottom of the winding shaft.

The brickmaking plant had been established and started to work.

The number of houses provided for the men was one detached house for the principal foreman, one Progress of the work—1882. for the Company’s chief inspector, one for the chief Storekeeper; six large cottages, and six smaller ones adjoining the Roman Camp; six semi-detached houses for foremen; a large coffee-house with a reading-room, and an adjoining house for the man keeping the coffee-room; twenty stone cottages closely adjoining the main shaft; and two stone semi-detached houses for foremen.

A mission-room with 250 sittings had also been completed, with schoolrooms behind, in which a day-school was carried on throughout the whole of the year; and at the end of the year a separate detached schoolroom of three rooms had been built, a certificated master appointed, and the school was put under Government inspection.

The principal office for the works, a large two-storied building, had been built, with a cottage adjoining, for the residence of the office-keeper.

At each shaft large rooms called ‘cabins’ had been built for the men to take their meals in, and where they could dry their clothes.

A saw-mill had been established, and a large carpenter’s shop.

Stables for twenty horses, with a cottage adjoining, had been built; also a new fitting-shop and blacksmith’s shops.

The roads to connect the new houses with the main roads had been completed, and in addition to the permanent houses, six wooden houses had been built near the brickyard for the men employed there.

Progress of the work—1882. On the Gloucestershire side of the river, where there was a difficulty in obtaining any land except directly over the tunnel, a number of wooden houses had been built, following the line of the tunnel. At this point I was afraid to put up brick houses, because the tunnel was to be constructed in gravel, and there would probably be serious settlement when the work was being carried on.

As soon as the 9-ft. barrel was completely bricked, in the middle of this year, a number of shafts were sunk to a depth of 20 feet, from which to put in the permanent drain required by the alteration of gradient. This when finished was to be a 5-ft. barrel.

The ground in which the drain was constructed was principally hard Pennant rock, but for a short distance it passed through the coal-shale. No great quantity of water was met with, and for the first 1,000 feet this was easily disposed of by hand-pumps. From the end of the 1,000 feet the water from this drain was pumped by the Schenk-pumps, which have been mentioned before.

The permission to commence the works at all points enabled us early in 1882 to largely increase the number of men employed; and as soon as the land was purchased, we commenced the open cuttings on both sides of the river.

The progress made during the whole of this year was very good, and there is little to record with regard to it, except that now and then some of those Progress of the work—1882. accidents, which are unavoidable in tunnel works, occurred.

The first of these took place about 60 yards east from the New Pit at Sudbrook, when we were getting out a length of tunnel in the last week of January, 1882.

The upper part of this length was entirely in coal-shale. The length was nearly ready for the bricklayers, and looked all secure, when a large mass of coal-shale in the face slipped out off a concealed bed of rock, which stood at an angle of about 45 degrees, and in slipping knocked out the whole of the props under the sills. The knocking out of these props caused the sills to break; the upper part of the face then also slipped in, and we ‘lost the length.’ This was the only length we lost in the whole tunnel; and as the total number of lengths taken out was over 1,500, it shows that great care was exercised by the foremen and the miners, to be able to say that only one length of the 1,500 was lost.

The losing of a length in such ground was, however, a serious matter.

It was under the river, but fortunately there were the hard beds of Pennant and conglomerate above the coal-shale, so that we had no reason to fear that the water would break into us.

As quickly as possible the top was secured, and then one of the most difficult operations in mining was commenced, viz., to pole through the broken ground.

|

| Sir John Hawkshaw inspecting the works. |

|

| At work in the tunnel. |

Whereas the length itself had been taken out in a fortnight, it took more than two months to take it out the second time.

Towards the end of February, Sir John Hawkshaw for the first time passed through the whole of the heading under the river. The work was then to be seen in all stages of progress. The old timbering, which had been put in before 1879, was also to be seen; and the points where the roof had fallen in, in consequence of insufficient timbering.

There were at that time about ten break-ups at work, half of them in hard rock, and half of them, on the east side of the river, in the red marl.

Early in April the brush electric light system was brought into operation on the works on the Gloucestershire side of the river. This was a 12-light system, and was used for lighting the top and the bottom of the pit, the spoil-bank on which the skips were tipped, and the length of tunnel where the arch was completed; each light was of 2,000 candle-power.

Shortly afterwards, a 40-light system was started on the Monmouthshire side of the river. The cable from this dynamo was 5 miles long, lighting the yard at Sudbrook, and the top of the pits there, the roads leading to the works, the top and the bottom of the pits at 5 miles 4 chains, and the top and bottom of the pits at both Marsh and Hill; and wherever the arch of the tunnel was completed for Progress of the work—1882. a distance of 100 yards, the lights were also instituted underground.

Electric lighting was comparatively in its infancy at the time this plant was erected, and I was advised that it was preferable to lay the cable (which was an insulated cable containing seven copper wires) in boxes underground, buried in cement concrete. It was supposed that there would be considerable danger to the men if the cables, though insulated, were carried upon poles above the surface of the ground; but a very short experience convinced us that it was impossible to work with the cables underground.

When any quantity of water made its way into the boxes, a current was set up between the two cables, and the wires rapidly fused. In consequence of this, a great deal of trouble was experienced with the light at first; and ultimately the whole of the cable was taken up, and fixed upon poles at least 15 feet above the surface of the ground, when the light was found to act admirably.

This light was a great advantage both for working on the surface at night and for the men running out skips from the lengths below—one great advantage being, that it generated little or no heat; but of course we could not use these lamps in the lengths that were at work, on account of the blasting. And even in those places where a man could work by the electric light, we generally found that he placed a candle in front of him on account of the deep shadow thrown by the light from his own body.

Progress of the work—1882. In the course of this year we also established a telephone from the works under the river to the Gloucestershire side. The first day it was at work it was, I believe, the means of averting a strike, for just as the principal foreman happened to go into one cabin, a discontented ganger entered the other, swearing and grumbling, and saying what he would do if some fancied grievance were not put right, and what he would advise the men to do. He little thought all he was saying was heard by his ‘boss;’ but his instant dismissal prevented further mischief.

During the year 1880 the progress which could be made with the works was only at the rate of about £4,000 worth of work done per month.

During the year 1881 the progress after the water was got out, but while the operations were confined to the work under the ‘Shoots’ and to the new shafts, was only at the rate of about £7,000 per month; but directly permission to proceed with the whole of the works was given, the progress rose rapidly, and was £11,000 in the month of January, 1882, and £23,000 per month before the end of the year.

In the beginning of 1882 one of the largest of the cottages had been temporarily converted into a cottage hospital, with a nurse employed to carry on a proper system of nursing under the doctor in charge.

An arrangement had been made with Dr. Lawrence, one of the leading doctors in Chepstow, to take entire charge of the men upon the work, and Progress of the work—1882. to keep a resident assistant there. Early in the summer the erection of a separate cottage hospital had been commenced, which included a residence for a matron, rooms for the resident doctor, for a sister to superintend the nursing, and for an assistant nurse.

This hospital was completed and opened in the second week in October. A plan showing the arrangement of the wards and the dwelling-house is given.

Considering the magnitude of the undertaking, the difficulties encountered, and the number of men employed night and day, we were very free from accidents during the six years the works were in progress; but still we found the hospital of the greatest value in treating both accidents and diseases, such as congestion of the lungs, rheumatic fever, etc. The principal illness that the men suffered from was pneumonia, caused no doubt by the great heat and damp below, and then careless exposure when they came out of the works.

Besides the general wards in the hospital, we had an operating-room, an emergency-ward, and a ward for women and children.

It has been before stated that the mission-room to hold 250 was opened in the end of the year 1880. By the end of November, 1881, this room was so crowded that it became necessary to take down the partition which separated the schoolrooms from the mission-room, to remove the day-school entirely into

the new rooms that had been built for it, and to enlarge the mission-room to hold 400. By the middle of November, 1882, this room was crowded, nearly 500 people attending every Sunday evening, the people sitting all up the aisles, and a number standing. I had a plan made for enlarging this room, but the difficulties in the way of doing so were very great, because it stood in close proximity to the new day-school, and any enlargement would take away the light from the windows of the school. The day-school itself was also crowded, and I was in great doubt as to what was the proper thing to do under the circumstances. The mission-room was heated by hot-air flues passing under the aisles; and after service on the 26th November, 1882, when the room had been terribly over-crowded and exceedingly hot, a fire broke out in the night, and the whole building was burned to the ground.

A policeman who passed on his rounds at midnight stated that he saw no signs of fire; but about three o'clock in the morning, the driver of one of the Cornish pumping-engines, looking out of the window of his engine-house, saw the mission-room alight from end to end. The alarm was immediately given, but the fire had already a complete hold of the room. All the seats and the roof were of pitch-pine, and in less than an hour the roof fell in and the room was destroyed. All the books and the American organ were destroyed with it.

I had already leased three acres of land, closely Progress of the work—1882. adjoining this room, for building additional houses for the men; and on Monday morning, using to some extent the plans which had been prepared for enlarging the old room, we began a new and larger one. At ten o’clock the men commenced to dig the foundations. At one o’clock the masons started to build the walls. The electric light was put up to enable them to work night and day, and though frost interfered to some extent with the rapid progress of the work, a new mission-hall to seat 1,000 persons was completed on the 16th December, and opened for service on the 17th—less than three weeks from the time of the fire, so that the men were only kept two Sundays out of the room, and on these service was held in the large reading-room over the coffee-room, which was capable of holding 250 persons. A drawing is given of the new room.

Early in the year, the head-wall to the east of the Sea-Wall Shaft was removed, and the heading was commenced on the lowered gradient, going eastward from this shaft.

In order to work down to the lower gradient westwards from this shaft, small shafts were sunk, at intervals of about 60 yards, from the old heading to the new levels, and a small heading, 6 feet by 4 feet, was driven from shaft to shaft, till we by this means secured natural drainage for putting in the invert from Sea-Wall Shaft, westwards.

Break-ups were started through the whole length of the ‘Shoots,’ and the ground proving very good, Progress of the work—1882. lengths averaging 20 feet were taken out in the Pennant rock, and the arch pushed on rapidly. Although the rock was good at this point, and rapid progress was made, no length was allowed to be executed without timbering.

The arch was completed from 5 miles 4 chains pit to within 30 feet of the point where the Great Spring had broken in, in 1879. The heading was pushed forward westward from 5 miles 4 chains, and a break-up commenced in the conglomerate rock.

Every yard of ground that was opened at this pit gave additional quantities of water; and I found it necessary, in addition to the two 28-inch pumps which were working there, to put down two 18-inch plunger-pumps, worked by a large horizontal engine.

The Marsh Pit was lowered to the new gradient, and the two 15-inch plunger-pumps were refixed there. We had recommenced to drive the headings east and west, and a length of about 60 yards of tunnel was completed adjoining the pit. The old heading was lowered to the new gradient for a distance of about 200 yards westward from the pit, and a break-up had been commenced about 100 yards west of the pit.

The Hill Shaft had also been lowered to the altered levels, and two 15-inch plunger-pumps had been fixed in that shaft, with a new pumping-engine; and the heading had also been lowered for a distance of about 150 yards west of the pit, and a break-up started about 100 yards from the pit.

Progress of the work—1882. In the month of May, the large open cutting on the Gloucestershire side of the river was commenced.

In the original contract the quantity to be excavated in this cutting was only 366,000 yards; but by the lowering of the gradient the quantity had been increased to upwards of 800,000 yards. About 200,000 yards of this was to be used in forming the sea-bank around the cutting to protect it from any extraordinary tides, and this work, which was done by wheeling out from the sides of the cutting, was carried on through the whole of the year.

The Panic.

On Saturday, the 2nd December, six days after the mission-room had been destroyed by fire, I had been to the hospital to see some men who were there, when, coming, out of the hospital just before one o’clock, I was met by one of my people from the office, with a face exhibiting the most complete signs of terror. On asking what was the matter, he said: ‘The river is in, the tunnel is in!’ and this was all the answer I could get.

‘Where are the men?’

‘They are just coming up the shaft.’

I hurried to the top of the main shaft, and there I found between 300 and 400 men evidently in the greatest terror and distress. Some had lost part of their clothing; hardly one of them could speak from exhaustion; and they were anxiously watching for Progress of the work—1882. the arrival of the large cage, which was bringing up a further batch of men.

Every man was panting for breath, and excited to the last degree with fear.

I must say that my heart sank, and I feared the worst; but at that moment the cage arrived at the top with ten or twelve men, and a foreman, named Tommy Lester, who I knew had been working beyond the ‘Shoots.’ I turned to him eagerly, and said:

‘Lester, what did you see?’

‘I see nothin’, sir.’

‘What is it then?’

‘I don’t know, only the river’s in.’

‘Where were you working?’

‘In No. 8.’

‘And you saw nothing ?’

‘No. It was beyond me.’

I turned to another, and said:

‘Where were you working ?’

‘In the long heading.’

‘And what did you see?’

‘I see nothin’, but the river’s in.’

‘I think you are a pack of fools,’ I said; ‘I think a five-pound note will cure it all.’

My reason for saying this was that these points were beyond the ‘Shoots,’ and there the bed of the river was dry at low water; so that if any hole existed there we could stop it as we had done the hole in the Salmon Pool.

Progress of the work—1882. Just then the foreman of the Cornish pumps came up, and said:

‘I cannot understand it; there is no more water at the pumps.’

I walked over with him and with Mr. Simpson, one of my staff, to the edge of the river, and found the water from the discharge-culvert the same colour as usual; so I walked back to the pit, and said:

‘I am going below; who is going with me ?’

J. H. Simpson and Jim Richards jumped into the cage with me, and the signal to lower was given. On arriving at the bottom we found it perfectly dry, and four or five men sitting quietly on a piece of timber scraping their boots.

The principal foreman of the works, Joseph Talbot, who had reached the top of the shaft before me, had gone down the iron staircase in the pumping-shaft, thinking that the winding-shaft could not be used, and he proceeded at once up the heading to see what was the matter.

After passing beyond the 9-ft. barrel where the men had been at work, in several break-ups he found articles of the men’s clothing thrown in every direction—hats, neckerchiefs, leggings, waistcoats, everything which they could take off and throw away; besides this, nothing was to be seen but the ponies which had been employed drawing the skips to the bottom of the shaft.

Returning again to the top, I explained the Progress of the work—1882. condition of affairs, and my readers may imagine that there was no little chaff at the expense of the men who had run away under the influence of panic.

By degrees, by questioning one and another, the whole story was brought to light. The men had been working in break-ups, and also in extending the long heading on the new gradient. This heading passed under the old heading (being driven for some distance level, while the other rose 1 in 100) till it left sufficient ground overhead to commence a heading entirely under the original one. A considerable stream of water, about 2,000 gallons a minute, was always running down the old heading, and where the new heading started under the old one, the water was carried on one side in a wooden shoot. The upper part of this shoot was secured in a dam made of clay-puddle to prevent the water from falling over the whole face of the heading.

On the other side of the river, I have before stated that a length of bottom heading had been driven from a number of small shafts to reach the levels of the lowered gradient. The water flowing down this bottom heading rose up the last of the shafts, and a length of about 1,500 feet always had water in it. In making the junctions of this heading between the diffierent shafts where there was considerable water, all that the men could do was to break down the last piece of rock between two shafts by blasting, without being able to go back to enlarge the hole made by the shots, or to clear up the rock Progress of the work—1882. which had been displaced by blasting; the opening in the heading, therefore, between some of the shafts was probably very small, and some timber which had dropped down from the upper works had got into one of these holes and dammed back the water. The foreman on the Gloucestershire side, in order to let the water flow freely, had sent down a diver to remove this timber; and when the timber was removed, the water which had been dammed back escaped rapidly, and flowing down the long heading had overflowed the puddle ‘stank’ made by the miners in the bottom heading. They had sent out twice to raise this stank, when they found the water rising above it, and at last one of them, seeing the water come still more rapidly, was seized with panic, and he called out:

‘Escape for your lives, boys! the river’s in!' and the men had taken the alarm at once.

As they ran towards the shaft, the men in the other break-ups joined in the panic, and at last the whole stream of men—three or four hundred in number—ran for their lives to the winding-shaft at Sudbrook.

When passing through lengths of finished tunnel, they spread out in a disorderly crowd, running perhaps 20 feet wide; then they would come to a short length between two break-ups, where there was only a 7-ft. heading. Here they threw each other down, trampled upon each other, shouting and screaming; and then, to add to the disorder, the Progress of the work—1882. ponies in the various break-ups took the alarm, and galloped down in the direction of the winding-shaft, trampling on the prostrate bodies of the men.

One ganger, a little stout fellow, who was working at the 5-ft barrel, was, on account of his short legs and stout body, unable to keep up with the others; and he was said to have uttered the most piteous entreaties to the men to carry him, and not leave him to be drowned.

The principal foreman afterwards asked one of the men why he had thrown away his clothes.

‘To zwim, zur,' he said.

I fear he would have made a bad hand at swimming in a 7-ft. heading, if any large volume of water from the river had really entered the works.

When the men reached the top of the pit, the night-shift—which would go below at two o’clock—had already received their pay, and were gathering in preparation to descend. It may be imagined that these men cruelly chaffed the others who had come up, as soon as it was known that there was no danger below; and I have reason to think they reaped quite a harvest of neckties and other things, thrown away by the others, when they went down to their work.

It would be wrong for anyone reading this account to blame the men for cowardice. I am sure that a finer body of men could not be found in England. They were men who had had a thoroughly hard Progress of the work—1882. of training, and accustomed as they were to work in dangerous positions, and knowing every time they went below that each man took his life in his hand, they still went cheerfully to their work, and were no doubt as brave as Englishmen always are. But to understand how easily a panic spreads, under the circumstances, it would be necessary one’s self to be under the river, a mile away from the shaft, confined in a narrow space, with rocks dripping or running with water all round, with only the light of a stray candle here and there, and the most extraordinary sounds that ever greeted the ears of mortal man: first from the east, and then from the west, heavy timbers thrown down suddenly, with a noise that re-echoed through the whole of the works; then a stray shot fired in one direction, then a complete salvo of 50 or 60 shots from the other—every sound totally different from the sounds in the open air—all the surroundings such as must produce a feeling of awe and tension of the nerves; and then, when men following their dangerous employment heard others running by them below, shouting to them to escape for their lives for the river was in, would any man pause to consider, when he thought his life could only be saved by the rapidity of his flight, from an enemy against which he could not contend?

I do not blame the men for the panic; but I had a bad quarter of an hour myself, when it seemed as though the three years’ work was after all ending in failure.

Progress of the work—1882. We had also an amusing accident on the Gloucestershire side of the river just a fortnight before, which no doubt caused the men more easily to take alarm.

In driving the bottom heading from Sea-Wall Shaft in the red marl, at a point where we had reason to believe, from the borings which had been taken, that there were still 6 or 7 feet of strong marl over the roof of the heading, on the night of the 13th November, the men being shorthanded had stopped work at the face of the heading, and had been drawn away to other parts, when (at midnight) the crust of marl at the top of the heading—which proved to be only 6 inches thick, instead of 6 feet—had suddenly given way, and the gravel, which was alive with water, had poured into the bottom heading, and the wooden houses being directly over the tunnel at this place, one large brick chimney, which was between two houses, had gone straight down, like a ramrod into the barrel of a gun, into the heading below. The houses having been built of wood, on account of this danger being foreseen, were but slightly damaged, the floors being slightly bent against the hole through which the chimney had disappeared. The men, women, and children occupying the two houses were asleep, and none of them were injured; but it certainly was ridiculous to hear of the number of trousers and waistcoats, all containing money and watches, which had been hung upon nails driven into this chimney Progress of the work—1882. the night before, and which had gone down into the bowels of the earth.

By arrangement with the Post-Office authorities, we had in the course of this year obtained the establishment of a post-office, money-order office, and savings bank upon the works, and in the end of October we also secured a telegraph-office, which was a great accommodation and was largely used. The number of messages which passed through this office rose to 1,900 in 1883, and 2,100 in 1884, and nearly 4,000 in 1886.

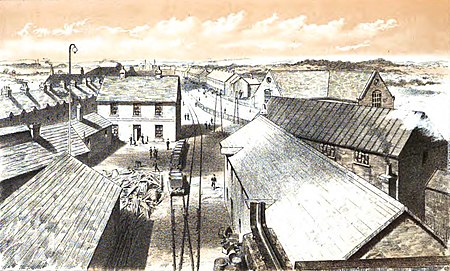

The Post-Office authorities, when this post-office was established, gave it the name of ‘Sudbrook,’ as they already had an office at Portskewett; and the settlement henceforth took the name of Sudbrook, and assumed quite the appearance of a small town.

Fourteen stone houses were built this year in the neighbourhood of the brickyard. Twenty were built, between the brickyard and Sudbrook Shaft, of concrete; and eighteen brick houses in further continuation of the same row. Four foremen’s houses, and the post-office, and ten more wooden houses were erected.

A plan is given showing the progress made with these buildings, and the year 1882 closed with the opening of the new mission-hall.

|

| The Works, Sudbrook |