The Zoologist/4th series, vol 2 (1898)/Issue 684/On the first Primary in certain Passerine birds

THE ZOOLOGIST

No. 684.—June, 1898.

ON THE FIRST PRIMARY IN CERTAIN PASSERINE BIRDS.

By Arthur Gardiner Butler, Ph.D., and Arthur George Butler, M.B. Lond.

In many Passerine birds the first primary is exceedingly small as compared with the second; and in the case of the families Fringillidæ, Motacillidæ, and Hirundinidæ, this feather has been authoritatively declared to be absent. As far back as Jerdon's time, and probably at a much earlier date, it was stated that these groups of birds possessed only nine primary quillfeathers; indeed, Dr. Jerdon notes this as the character which distinguishes the Ploceinæ and Estreldinæ, which are admitted to have a small first primary, from the other groups which he includes in his extended family Fringillidæ.[1]

In Seebohm's 'History of British Birds' we read:—"The Finches form a large group of birds which may at once be distinguished from all the other subfamilies of the Passeridæ by their combination of a stout conical bill with the entire absence of a first primary."

Of the Wagtails he says:—"The absence of a bastard or first primary sufficiently distinguishes them from the Thrushes, Tits, Crows, or Shrikes; and also from the Waxwings and Starlings, in which the bastard primary, though very small, is always present." Of the Hirundinidæ he says:—"They have no bastard primary."

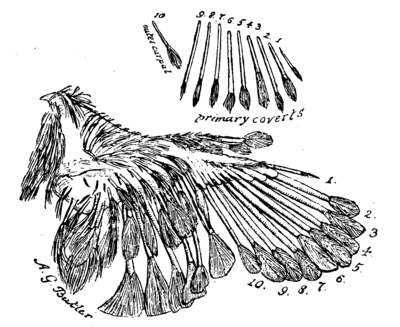

Some months ago the question arose between us as to the principal distinguishing characters of the Fringilline and Ploceine Finches, and (naturally) this difference of number in the primaries was the first structural point to be considered. Having a wing of the common Siskin and several wings of Waxbills and Mannikins, we examined the two types, and (to our unbounded astonishment), discovered the first primary well developed in both, but with this difference:—In the Fringillid bird the first primary was shorter than, and therefore completely concealed by, its upper covert; whereas in the Ploceid bird the first primary projected beyond its covert.

Thinking it quite impossible that, if this fact were common to all examples of all species of the two families, it could have been so long overlooked, we have gradually accumulated the wings of various species in which the first primary was declared to be absent, and we are bound to say that, not only have we never failed to find it in any species which we have examined, but that in some species, such as the Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and the Canary (Serinus canaria), it is far better developed than in many of the Ploceid Finches.

We have examined wings of the following species:—

Fringillidæ.—Chrysomitris spinus, C. tristis, C. totta; Serinus icterus, S. canaria, S. leucopygius; Carduelis carduelis; Acanthis cannabina, A. rufescens; Fringilla cœlebs, F. montifringilla; Passer domesticus; Pyrrhula pyrrhula; Guiraca cærulea; Chloris chloris; Cardinalis cardinalis; Alario alario.

Motacillidæ.—Motacilla melanope; Anthus trivialis, A. pratensis.

Hirundinidæ.—Hirundo rustica.

Being anxious to make no mistake, we were not content to examine single examples, but, wherever possible, carefully removed the lower coverts from several examples of each species; in no single instance did we fail to discover the small first primary, although in Motacilla melanope it is very minute and almost linear (narrowly hastate); in fact, we found it best developed in the Sparrow, and worst developed in the Grey Wagtail. Even yet, it seemed so strange that a feather which we always discovered easily should have been so long overlooked, that we were not convinced, but determined to obtain undeveloped wings of some species, in order to make quite certain of our fact before recording it.

From several nests of Passer domesticus, all of which unfortunately contained eggs only, one egg (incubated about nine days) contained a young bird from which a wing could be obtained. When placed under the microscope nine primaries were already commencing to appear from their follicles, but the first primary, the follicular depression of which was well defined, had not yet appeared.

A few days later, several young Canaries, which died seven and nine days after leaving the egg, were found to have all ten primaries, with their coverts, perfectly clearly developed; we were thus compelled to come to the conclusion that the accepted definition of these three families, Fringillidæ, Motacillidæ, and Hirundinidæ should be modified, and that, instead of the statement that the first primary is absent, the following should be substituted:—"The first primary is concealed within its coverts." It seems to us that the only explanation of the supposition that no first primary existed, is that the student has in every instance removed the concealed primary when taking off the under wingcoverts to trace the origin of the quills.

The examination of the wings of a Sparrow, recently taken from the nest when about ten days old, seems clearly to indicate that the so-called outer carpal covert replaces the tenth primary covert, and is homologous to that covert (which is absent); it certainly is identical with the feather which we accept as the tenth covert in the Canary and in other true Finches, as, for instance, in the Virginian Cardinal.

In the Icteridæ, which are said to differ from the Starlings in having only nine primaries, we have found the first primary in the Silky Cowbird, Brown-headed Troupial, Bobolink, Tedbreasted Marsh-bird, Military and Yellow-shouldered Troupials, and Brazilian Hangnest; indeed, the first primary, with its upper covert, are so conspicuous in these large birds, that they can frequently be seen without even using a needle to separate them from the second primary. In the Motacillidæ, where the first primary is very small and lies close to the second, it might easily be overlooked, but that a feather nearly (if not quite) half an inch long should have escaped observation is inexplicable.

- ↑ He included the Ploceine Finches, the Tanagers, and the Larks.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1925, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 98 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse