The fairy tales of science/The Age of Monsters

The Age of Monsters.

"Mighty pre-Adamites that walked the earth

Of which ours is the wreck."—Byron.

NCE upon a time—if we are to believe our Fairybooks—a terrible race of monsters devastated this fair earth. Dragons and Griffins roamed at large, and a passing visit from one of these rapacious creatures was held to be the greatest calamity that could befall a nation. All the King's horses and all the King's men were powerless in the presence of such a foe, and the bravest monarch stooped to purchase his own safety with the most humiliating concessions. The dragon was allowed to run riot over the face of the country; to devour the flocks and herds at his pleasure; and when sheep and oxen ceased to gratify him, scores of beautiful damsels were sacrificed to allay the cravings of his ravenous appetite.

Sometimes the fastidious monster would go so far as to order a princess for dinner, but he generally had to pay dearly for his audacity. When the monarch had exhausted his stock of prayers, and the poor little maiden had almost cried out her eyes, some valiant knight-errant was certain to come forward and challenge the dragon to meet him in the field. A terrific encounter then took place, and strange to say, the knight invariably proved himself to be more than a match for the destroyer who had hitherto kept whole armies at bay.

As instances of this wonderful triumph of Right over Might, we need only mention that celebrated duel in which the Dragon of Wantley was forced to succumb to the prowess of Moore of Moore Hall; and that still more famous combat in which the invincible St. George of England won an everlasting renown.

We have said that these monsters belonged to that mythical age known as "once upon a time;" unfortunately we can find no trace of them in authentic history, and we are compelled to admit that they had their origin in the fanciful brains of those old story-tellers whose wondrous legends we delight to linger over.

In more credulous times, however, these monsters of enchantment were religiously believed in, and no one doubted that they had their lairs in the dark and impenetrable forests, in the desolate mountain passes, and in those vast and gloomy caverns which are even now regarded with superstitious dread by the ignorant.

At length the lamp of science was kindled, and its beneficent rays penetrated the darkest recesses of the earth; roads were cut through the tangled woods, busy factories sprang up in the lonely glens, and curious man even ventured to pry into the secrets of those terrible caves. The monsters of romance were nowhere to be found. Triumphant science had banished them from the realms of fact, with the same pitiless severity that the uncompromising St. Patrick had previously displayed towards the poisonous reptiles of Ireland.

The poor ill-used Dragon has now no place to lay his scaly head, the Griffin has become a denless wanderer, and the Fiery Serpent has been forced to emigrate to a more genial clime!

Fortunately truth is stranger than fiction; the revelations of modern science transcend the wildest dreams of the old poets; and in exchange for a few shadowy griffins and dragons, we are presented with a whole host of monsters, real and tangible monsters too, who in the early days of the world's history were the monarchs of all they surveyed, and had no troublesome Seven Champions to dispute their sway.

We are on the shores of the Ancient Ocean. We search in vain for any sign of Man's handiwork; no iron steam-ship, no vessel of war, no rude canoe even, has yet been launched upon its bosom, though the tides ebb and flow, and the waves chant their eternal hymn, according to those immutable laws which the Creator ordained at the beginning.

The ocean teems with life, but it contains no single creature which has its exact likeness in modern seas. Its fishes belong for the most part to the great Shark family, but their forms are much more uncouth than those of their savage descendants. No whales, dolphins, nor porpoises are to be found in these waters, their places being filled up by strange marine reptiles, which equal them in bulk, and greatly surpass them in voraciousness.

Yonder is one of these old monsters of the deep:[1] as it rests there with its broad back glistening in the sun, it might easily be mistaken for some rocky islet—but see, it moves! Now it lashes the water with its enormous tail, creating quite a whirlpool in its neighbourhood—now it raises its huge head, and displays a row of teeth at which the bravest might shudder—and now it darts away from the shore, leaving a wide track of foam on the dark blue waters.

Another member of the Saurian or Lizard race is disporting himself in a little bay close by. The imagination of man never called up a shape so weird and fantastic as this, in which we see combined, a fish-like body, a long serpentine neck, and the tapering tail of a lizard.[2] As he paddles through the water with his neck arched over his back in a graceful curve, he looks a very handsome fellow, in spite of the somewhat evil expression of his countenance; but he is anything but handsome, if we judge him by the adage which restricts the use of that epithet to handsome doers. Look at him now, how eagerly he pounces upon every living thing that comes within the range of his pliant neck, how cruelly he crushes the bones of his victims, and how greedily he swallows them! We never witnessed such unhandsome conduct in a monster before. Leaving him at his disgusting banquet, let us now penetrate into the interior of the old continent, where we shall encounter some terrestrial reptiles of a very formidable character.[3]

We are in the heart of a strange wild country. At our feet runs a mighty river, whose tortuous course we can trace far away on the distant landscape. The scenery around us is grandly picturesque, being diversified by high mountains with harsh and rugged outlines, yawning chasms, swampy plains, and thick forests. Here a broad stream dashes impetuously through a narrow glen, and there a placid lake glistens like polished silver. Huge masses of rock arise in a thousand fantastic forms on one side, while on the other vast desert tracts, monotonously level, spread out as far as the eye can reach.

The general aspect of the country is utterly unlike that of any modern land, and we gaze on the savage panorama before us with mingled feelings of admiration and awe. We are surrounded by wonders. The vegetation which fringes the banks of the river is strangely unfamiliar. Some of the trees remind us of the palms and arborescent ferns of the Tropics, and others seem to be allied to the cypress and juniper, but they all belong to unknown species.

The air, which is hot and oppressive, swarms with insects; curious flies and beetles hum around us, and every now and then a huge dragon-fly darts past like a meteor.

Looking towards the river, other more striking forms of animal life meet our gaze. Hundreds of gigantic crocodiles are swimming in the stream and lying on the muddy shore; horrible creatures are they, with their thick coats of mail and sharp elongated muzzles, and we cannot watch their ungainly movements without experiencing an involuntary sensation of disgust.

On the oozy banks of the river another type of reptilian life is represented by a shoal of freshwater Turtles which we see crawling along at a slow and steady pace. Now one of these sluggish fellows stops to pick up some dainty morsel (a mussel, perhaps, a snail, or a crocodile's egg), but the exertion appears to cost him no small annoyance, and now he draws in his head and prepares for a nap. As he has in all probability a hundred years yet to live, he can afford to devote an hour or two to digestion.

But hark! What noise was that? Surely that harsh discordant roar must have proceeded from the deep throat of some monster concealed in yonder forest. The Crocodiles seem to understand it perfectly, for see, they are making for the opposite bank with most undignified speed. There it is again, still louder than before! Now a crashing among the trees, followed by a wild unearthly shriek.

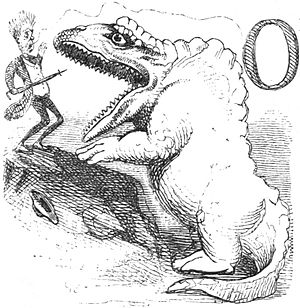

Look at that terrible form which has just emerged from the thicket. It rushes towards us, trampling down the tall shrubs that impede its progress as though they were but so many blades of grass. Now it stops as if exhausted, and turns its huge head in the direction of the forest.

How shall we describe this monster of the old world, which is so unlike any modern inhabitant of the woods? Its body, which is at least twenty feet long, is upheld by legs of proportional size, and a massive tail, which drags upon the ground and forms a fifth pillar of support. Its head is hideously ugly, its immense jaws and flat forehead recalling the features of those grim monsters which figure in our story-books. Its dragon-like appearance is still further increased by a ridge of large triangular bones or spines which extends along its back.[4] We should not be at all surprised were we to see streams of fire issuing from the mouth of this creature, and we look towards the palm-forest half expecting a St. George to ride forth on his milk-white charger.

See!—some magic power causes the trees to bend and fall—the dragon-slayer is approaching! Gracious powers! It is not St. George, but another Dragon nearly double the size of the first. He proclaims his arrival by a loud roar of defiance, which is unanswered save by the echoes of the surrounding hills. The first monster tries to conceal himself behind a clump of trees and preserves a discreet silence, being evidently no match for his formidable challenger. The new comer is certainly a very sinister-looking beast. His magnitude is perfectly astounding. From the muzzle to the tip of his tail he seems to measure about forty feet, and his legs are at least two yards long. His feet are furnished with sharp claws for tearing the flesh from the bones of his victims, and his teeth are fearful instruments of destruction, each tooth being curved, and pointed like a sabre, with jagged saw-like edges.[5] His disposition is decidedly unamiable. Look at him now—how furiously he tears up the earth, and how savagely he looks about him for some trace of his lost prey! Now he catches a glimpse of the crested monster among the trees, and dashes towards him with a terrific yell of delight.

Alas! there is no escape for you, unfortunate Dragon! The great monster can outstrip you in the chase, and you may as well show a bold front.

Now they meet in the hollow with a fearful crash. The lesser monster is determined to sell his life dearly, and with the aid of the spines along his back he contrives to inflict some severe wounds upon the huge body of his opponent.

What a fearful conflict! How they snort and roar! Now they roll over among the ferns, linked together in a terrible embrace. The hero of the crest is the first to rise—he makes off towards the forest, and may yet escape. Alas! he falls exhausted, and the great monster is on his track. His temper does not seem to be improved by his wounds—how angrily he tosses his head, and how fiercely he gnashes his sabre-like teeth. He approaches his fallen enemy. Now he jumps upon him with a crushing force, and now his enormous jaws close upon the neck of his victim, who expires with a shriek of pain.

We can gaze no longer at this awful scene. The battle was sufficiently exciting to absorb our attention, but we have no desire to see how the great monster disposes of the body of his valiant foe. Let us therefore leave the river bank, and visit another portion of the old continent.

We stand in a lovely valley surrounded on all sides by high mountains, whose slopes are covered with luxuriant vegetation. A crystal stream meanders through the fertile plains, and runs into a fairy-like lake, upon whose margin there are little groups of arborescent ferns and palms. The whole valley has the appearance of a rich garden, and we regard its varied beauties with rapturous admiration.

As we look around we fail to discover any trace of man—no temple, palace, nor hut bears witness to the existence of a being capable of appreciating the charms of which nature has been so prodigal. We are profound egotists, and think that everything beautiful must have been created for our especial advantage. Here, however, trees spring up though there be no woodman to hew them down, fruits ripen though there be none to gather them, and the stream flows though there be no mill to set in motion; in fact, the age of man has not yet dawned upon the earth.

We have already seen some of the weird inhabitants of the Old World; this valley is the favourite haunt of another and a still more remarkable creature, who loves the shelter which these trees afford.

Yonder is one of these extraordinary monsters. He has just emerged from the forest, and is marching towards the lake slowly and majestically, a regular moving mountain! His legs are like trunks of trees, and his body, which rivals that of the elephant in bulk, is covered with scales. In length and height he equals the great lizard we have already described, but his whole appearance is far less awe-inspiring. There is a good-humoured expression in his face, and his teeth are not nearly so formidable as those of his predacious neighbour, being blunt and short, and evidently fitted for the mastication of vegetable food.[6]

Look! he is quietly grazing on those luxuriant ferns which lie in his path. Now the foliage of a tall palm-like tree seems to offer a tempting mouthful, but it is beyond his reach: there are more ways than one of procuring a meal—see, the huge vegetarian places his fore-paws against the stem of the tree and coolly pushes it down. Having stript the fallen stem of its sword-like leaves, he plunges in the lake, and flounders about in the water as though the bath were his greatest source of enjoyment. This huge herbivorous monster would probably be no match for the cruel creature whom we left devouring his enemy by the river, as all its actions prove it to be a harmless and peaceably disposed animal.

Look at that strange bird overhead! Its body does not appear to be larger than that of a pigeon—but what enormous wings it is provided with! Now it descends. Is it a bird or a large bat? Its wings seem to be formed of leather, and its body has anything but a bird-like form. See! it alights, and runs upon the ground with considerable speed—now it jumps into the lake, and swims about the surface as if water were its natural element. Again it rises in the air, directing its course towards the spot where we are standing, and now it perches upon a fragment of rock close to us.

What an extraordinary creature; it is neither bird nor bat, but a winged reptile! Its head, which is small and bird-like and supported on a long slender neck, is provided with elongated jaws, in which are set some fifty or sixty sharp little teeth. Its wing consists of folds of skin, sustained by the outer finger enormously lengthened; the other fingers being short and armed with powerful claws. Its body is covered with scales instead of feathers, and in addition to this strange mixture of bird-like and reptilian features, the creature is provided with the long stiff tail of a mammal.[7]

Of all the inhabitants of this country of marvels, the Flying reptile is by far the strangest; and as we gaze upon its weird form, we cannot help comparing it with, one of those horrible and grotesque imps which are described so minutely in monkish legends.

Again the scene changes—the country of the monster fades away, and we are once more in our cosy study, surrounded by our favourite volumes.

Perhaps the curious reader would like to know where the marvellous country is situated, but as we do not intend to tack a long scientific essay upon our fairy-tale, he must be content with a very few words of explanation.

All that remains of the monsters' country is a large tract of land or delta which was formed ages and ages ago at the mouth of a mighty river.[8] The continent through which this river flowed now forms a large portion of the bed of the Atlantic.

How can we know anything about this submerged country?—how can we come to any conclusion respecting the kind of creatures which lived and died there? These questions will probably occur to the reader, and give rise to certain doubts as to the credibility of our narrative.

The monsters have been their own historians. They have described themselves in the gorgeously illuminated volume called the Stone Book, every page of which is formed of the solid rock. The truth of the matter is simply this; when the geologist came to examine the structure of the old river delta, he found embedded in the rocks, broken and water-worn bones, detached teeth, fresh-water shells, fragments of trees, and even the bodies of insects. With untiring industry and perseverance he classified these organic remains; he placed together the gigantic bones, and reproduced the forms of those enormous creatures which are now represented by our tiny frogs and lizards; he examined every leaf and fir-cone, and found out the order of plants to which they belonged—every relic he submitted to a close scrutiny, and at length he was rewarded by a vision of the ancient continent and its inhabitants as they existed at that remote period which we can only vaguely describe as "once upon a time."

- ↑ The Cetiosaurus, or Whale-like Lizard

- ↑ The Plesiosaurus

- ↑ The Dinosaurians, or fearfully-great Lizards.

- ↑ The Hylæosaurus, or Wealden Lizard.

- ↑ The Megalosaurus, or Great Lizard.

- ↑ The Iguanodon, so named from its teeth, which resemble those of a recent lizard called the Iguana.

- ↑ The Pterodactyle, or Wing-fingered Lizard.

- ↑ The Wealden Beds, so called from their forming a district known as the Weald of Kent and Sussex. These strata, which were deposited at the mouth of a river rivalling the Mississippi in magnitude, occupy the whole area between the North and South Downs.