The food of the Gods - A Popular Account of Cocoa/Its Growth And Cultivation

"THE FOOD OF THE GODS."

II. ITS GROWTH AND CULTIVATION.

COCOA is now grown in many parts of the tropics, reference to which is made in another

|

chapter. The conditions, however, do not greatly vary, and there are probably many lands in the tropical belt where it is yet unknown that possess soil well suited to its extended cultivation.

The cacao-tree grows wild in the forests of Central America, and varieties have been found also in Jamaica and other West Indian islands, and in South America. It does not thrive more than fifteen degrees north or south of the equator, and even within these limits it is not very successfully grown more than 600 feet above the sea-level; in many districts where sugar formerly monopolized the plains, it was supposed that cocoa needed an altitude of at least 200 feet, but experiments of planting on the old sugar estates and other low-lying places are generally successful where the soil is good, as in Trinidad, Cuba, and British Guiana. It has been found that the expense saved in roads, labour, and transit on the level has been very considerable in comparison with that incurred on some of the hill estates.

In appearance the cacao-tree is not greatly unlike one of our own orchard trees, and trained by the pruning knife it grows similar in shape to a well-kept apple tree, no very low boughs being left, so that a man on horseback can generally pass freely down the long glades. Left to nature, it will in good soil reach a height of over twenty feet, and its branches will extend for ten feet from the centre.

Ceylon: Nursery of Cacao Seedlings in Baskets of plaited Palm Leaf.

The best soil is that made by the decomposition of volcanic rock, so that it is a common sight to find areas strewn with large boulders turned into a cocoa plantation of great fertility; but the best trees of all lie along the vegas which intersect the hills, where the soil is deep, and the stream winding among the trees supplies natural irrigation. The tree also grows well in loams and the richer marls, but will not thrive on clay and other heavy soils.

The cacao is one of the tenderest of tropical growths, and will not flourish in any exposed position, for which reason large shade belts are left along exposed ridges and other parts of a hill estate, thus greatly reducing the total area under cultivation, in comparison with an estate of equal extent on the level plains, where no shade belts are necessary.

The beans are planted either "at stake,"—when three beans are put in round each stake, the one thriving best after the first year being left to mature,—or "from nursery," whence, after a few months' growth in bamboo or palm-leaf baskets, they are transplanted into the clearing. The preparation of the land is the first and greatest expense; trees have to be felled, and bush cut down and spread over the land, so that the sun can quickly render it combustible. When all is clear, the cacao is put in among a "catch crop" of vegetables (the cassava, tania, pigeon-pea, and others), and frequently bananas, though, as taking more nutriment from the soil, they are sometimes objected to. But the seedling cacao needs a shade, and as it is some years before it comes into bearing, it is usual to plant the "catch crop" for the sake of a small return on the land, as well as to meet this need.

In Trinidad, at the same time that the cacao [1] is planted at about twelve feet centres, large forest trees are also planted at from fifty to sixty feet centres, to provide permanent shade. The tree most used for this purpose is the Bois Immortelle (Erythrina umbrosa); but others are also employed, and experiments are

Samoa: Cacao in its fourth Year.

now being made on some estates to grow rubber as a shade tree. In recent clearings in Samoa, trees are left standing at intervals to serve this end.

In Grenada, British West Indies, and some other districts, shade is entirely dispensed with, and the trees are planted at about eight feet centres, thus forming a denser foliage. By this means at least 500 trees will be raised on an acre, against less than 300 in Trinidad, the result showing almost invariably a larger output from the Grenada estates. This practice is better suited to steep hillside plantations than to those in open valleys or on the plains.

The cacao leaves, at first a tender yellowish-brown, ultimately turn to a bright green, and attain a considerable size, often fourteen to eighteen inches in length, sometimes even larger. The tree is subject to scale insects, which attack the leaf, also to grubs, which quickly rot the limbs and trunks, this last being at one time a very serious pest in Ceylon. If left to Nature the trees are quickly covered with lichen, moss, "vines," ferns, and innumerable parasitic growths, and the cost of keeping an estate free from all the natural enemies which would suck the strength of the tree and lessen the crop is very great.

The cacao will bloom in its third year, but does not bear fruit till its fourth or fifth. The flower is small, out of all proportion to the size of the mature fruit. Little clusters of these tiny pink and yellow blossoms show in many places along the old wood of the tree, often from the upright trunk itself, and within a few inches of the ground; they are extremely delicate, and a planter will be satisfied if every third or fourth produces fruit. In dry weather or cold, or wind, the little pods only too quickly shrivel into black shells; but if the season be good they as quickly swell, till, in the course of three or four months, they develop into full grown pods from seven to twelve inches long. During the last month of ripening they are subject to the attack of a fresh group of enemies—squirrels, monkeys, rats, birds, deer, and others, some of them particularly annoying, as it is often found that when but a small hole

Young Cultivation, with catch Crop of Bananas, Cassava, and Tania: Trinidad.

has been made, and a bean or so extracted, the animal passes on to similarly attack another pod; such pods rot at once. Snakes generally abound in the cacao regions, and are never killed, being regarded as the planters best friends, from their hostility to his animal foes. A boa will probably destroy more than the most zealous hunter's gun.

PODS OF CACAO THEOBROMA.

From its twelfth to its sixtieth year, or later, each tree will bear from fifty to a hundred and fifty pods, according to the season, each pod containing from thirty-six to forty-two beans. Eleven pods will produce about a pound of cured beans, and the average yield of a large estate will be, in some cases, four hundredweight per acre, in others, twice as much. The trees bear nearly all the year round, but only two harvests are gathered, the most abundant from November to January, known as the "Christmas crop," and a smaller picking about June, known as the "St. Johns crop." The trees throw off their old leaves about the time of picking, or soon after; should the leaves change at any other time, the young flower and fruit will also probably wither.

Of the many varieties of the cacao, the best known are the criollo, forastero, and calabacilla. The criollo ("native") fruit is of average size, characterized by a "pinched" neck and a curving point. This is the best kind, though not the most productive; it is largely planted in Venezuela, Columbia and Ceylon, and produces a bean light in colour and delicate in flavour. The forastero ("foreign") pod is long and regular in shape, deeply furrowed, and generally of a rough surface. The calabacilla ("little calabash") is smooth and round, like the fruit after which it is named. All varieties are seen in bearing with red, yellow, purple, and sometimes green

Varieties of the Cacao.

pods, the colour not being necessarily an indication of ripeness.

On breaking open the pod, the beans are seen clinging in a cluster round a central fibre, the whole embedded in a white sticky pulp, through which the red skin of the cacao-bean shows a delicate pink. The pulp has the taste of acetic acid, refreshing in a hot climate, but soon dries if exposed to the sun and air. The pod or husk is of a porous, woody nature, from a quarter to half an inch thick, which, when thrown aside on warm moist soil, rots in a day or two.

Much has been written of life on a cocoa estate; and all who have enjoyed the proverbial hospitality of a West Indian or Ceylon planter, highly praise the conditions of their life. The description of an estate in the northern hills of Trinidad will serve as an example. The other industry of this island is sugar, in cultivating which the coloured labourers work in the broiling sun, as near to the steaming lagoon as they may in safety venture. Later on in the season the long rows between the stifling canes have to be hoed; then, when the time of "crop" arrives, the huge mills in the usine are set in motion, and for the longest possible hours of daylight the workers are in the field, loading mule-cart or light railway with massive canes. In the yard around the crushing-mills the shouting drivers bring their mule-teams to the mouth of the hopper, and the canes are bundled into the crushing rollers with lightning speed. The mills run on into the night, and the hours of sleep are only those demanded by stern necessity, until the crop is safely reaped and the last load of canes reduced to shredded megass and dripping syrup.

But upon the cocoa estate there is lasting peace. From the railway on the plain we climb the long valley, our strong-boned mule or lithe Spanish horse taking the long slopes at a pleasant amble, standing to cool in the ford of the river we cross and re-cross, or plucking the young shoots of the graceful bamboos so often fringing our path. Villages and stragglin cottages, with palm thatch and adobe walls, are

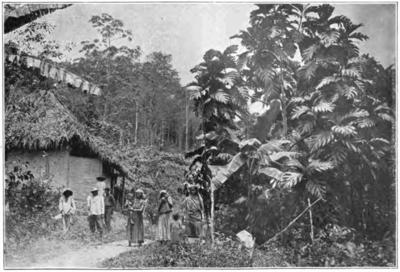

The Home of the Cacao.

(One of Messrs. Cadburys' Estates, Maracas, Trinidad.)

passed, orange or bread-fruit shading the little garden, and perhaps a mango towering over all. The proprietor is still at work on the plantation, but his wife is preparing the evening meal, while the children, almost naked, play in the sunshine.

The cacao-trees of neighbouring planters come right down to the ditch by the roadside, and beneath dense foliage, on the long rows of stems hang the bright glowing pods. Above all towers the bois immortelle, called by the Spaniards la madre del cacao, "the mother of the cacao." In January or February the immortelle sheds its leaves and bursts into a crown of flame-coloured blossom. As we reach the shoulder of the hill, and look down on the cacao-filled hollow, with the immortelle above all, it is a sea of golden glory, an indescribably beautiful scene. Now we note at the roadside a plant of dragon's blood, and if we peer among the trees there is another just within sight; this, therefore, is the boundary of two estates. At an opening in the trees a boy slides aside the long bamboos which form the gateway, and a short canter along a grass track brings us to the open savanna or pasture around the homestead.

Here are grazing donkeys, mules, and cattle, while the chickens run under the shrubs for shelter, reminding one of home. The house is surrounded with crotons and other brilliant plants, beyond which is a rose garden, the special pride of the planter's wife. If the sun has gone down behind the western hills, the boys will come out and play cricket in the hour before sunset. These savannas are the beauty-spots of a country clothed in woodland from sea-shore to mountain-top.

Next morning we are awaked by a blast from a conch-shell. It is 6.30, and the mist still clings in the valley; the sun will not be over the hills for another hour or more, so in the cool we join the labourers on the mule-track to the higher land, and for a mile or more follow a stream into the heart of the estate. If it is crop-time, the men will carry a goulet—a hand of steel, mounted on a long bamboo—by the sharp edges of which the pods are cut from the higher branches without

Ortinola, Maracas, Trinidad.

injury to the tree. Men and women all carry cutlasses, the one instrument needful for all work on the estate, serving not only for reaping

GOULET AND WOODEN SPOON.

the lower pods, but for pruning and weeding, or "cutlassing," as the process of clearing away the weed and brush is called.

CUTLASSES.

Gathering the pods is heavy work, always undertaken by men. The pods are collected from beneath the trees and taken to a convenient heap, if possible near to a running stream, where the workers can refill their drinking-cups for the mid-day meal. Here women sit, with trays formed of the broad banana leaves, on which the beans are placed as they extract them from the pod with wooden spoons. The result of the days work, placed in panniers on donkey-back, is "crooked" down to the cocoa-house, and that night remains in box-like bins, with perforated sides and bottom, covered in with banana leaves. Every twenty-four hours these bins are emptied into others, so that the contents are thoroughly mixed, the process being continued for four days or more, according to circumstances.

This is known as "sweating." Day by day the pulp becomes darker, as fermentation sets in, and the temperature is raised to about 140° F. During fermentation a dark sour liquid runs away from the sweat-boxes, which is, in fact, a very dilute acetic acid, but of no commercial value. During the process of "sweating" the cotyledons of the cocoa-bean, which are at first a purple colour and very compact in the skin,

Cacao Drying in the Sun, Maracas, Trinidad.

lose their brightness for a duller brown, and expand the skin, giving the bean a fuller shape. When dry, a properly cured bean should crush between the finger and thumb.

Finally the beans are turned on to a tray to dry in the sun. They are still sticky, but of a brown, mahogany colour. Among them are pieces of fibre and other "trash" as well as small, undersized beans, or "balloons," as the nearly empty shell of an unformed bean is called. While a man shovels the beans into a heap, a group of women, with skirts kilted high, tread round the sides of the heap, separating the beans that still hold together. Then the beans are passed on to be spread in layers on trays in the full heat of the tropical sun, the temperature being upwards of 140° F.[2] When thus spread, the women can readily pick out the foreign matter and undersized beans. Two or three days will suffice to dry them, after which they are put in bags for the markets of the world, and will keep with but very slight loss of weight or aroma for a year or more. Between crops the labourers are employed in "cutlassing," pruning, and cleaning the land and trees. Nearly all the work is in pleasant shade, and none of it harder than the duties of a market gardener in our own country; indeed, the work is less exacting, for daylight lasts at most but thirteen hours, limiting the time that a man can see in the forest: ten hours per day, with rests for meals, is the average time spent on the estate. Wages are paid once a month, and a whole holiday follows pay-day, when the stores in town are visited for needful supplies. Other holidays are not infrequent, and between crops the slacker days give ample time for the cultivation of private gardens.

Labourers from India are largely imported by the Government under contract with the planters, and the strictest regulations are observed in the matter of housing, medical aid, etc. At the expiration of the term of contract (about six years) a free pass is granted to return to India, if desired. Many, however, prefer to remain in their adopted home, and become planters themselves, or continue to

Labourer's Cottage, Cacao Estate, Trinidad.

(Bread Fruit and Bananas)

labour on the smaller estates, which are generally worked by free labour, as the preparations for contracted labour are expensive, and can only be undertaken on a large scale.

The natives of India work on very friendly terms with the coloured people of the islands, the descendants of the old African slaves, and

BASKETS OF CACAO ON PLANTAIN LEAVES.

the cocoa estate provides a healthy life for all, with a home amid surroundings of the most congenial kind.[3]

In other cocoa-growing countries processes vary somewhat. On the larger estates artificial drying is slowly superseding the natural method, for though the sun at its best is all that is needed, a showery day will seriously interfere with the process, even though the sliding roof is promptly pulled across to keep the rain from the trays.

In Venezuela an old Spanish custom still prevails of sprinkling a fine red earth over the beans in the process of drying; this plan has little to recommend it, unless it be for the purpose of long storage in warehouses in the tropics, when the "claying" may protect the bean from mildew and preserve the aroma. In Ceylon it is usual to thoroughly wash the beans after the process of fermentation, thus removing all remains of the pulp, and rendering the shell more tender and brittle. Such beans arrive on the market in a more or less broken state, and it seems probable that they are more subject to contamination owing to the thinness of the shell. The best "estate" cocoa from Ceylon has a very bright, clear appearance, and commands a high price on the London market; this cocoa is of the pure criollo strain, light brown (pale burnt sienna) in colour.

The valleys of Trinidad and Grenada have

Cacao Tree and Seedling

grown cocoa for upwards of a hundred years, but up to the present time very little in the way of manuring has been done beyond the natural vegetable deposits of the forest. In many estates of recent years cattle have been quartered in temporary pens on the hills, moving on month by month, with a large central pen for the stock down on the savanna.

The cocoa-beans are shipped to Europe in bags containing from one to one and a half hundredweight, and are disposed of by the London brokers nearly every Tuesday in the year at a special sale in the Commercial Sale Room in Mincing Lane.

The cacao-tree has sometimes been grown from seed in hot-houses in this country, but always with difficulty, for not only must a mean temperature of at least 80° F. be maintained, but the tree must be shielded from all draught. Among the most successful are the trees grown by Mr. James Epps, Jun., of Norwood, by whose kind permission the accompanying sketches from life were made. Success has only crowned his efforts after many years of patient care. To grow a mere plant was comparatively simple, but to produce even a flower needed long tending, and involved much disappointment; while to secure fruition by cross-fertilization was a still more difficult task, accomplished in England probably on only one other occasion.

Bournville: "The Factory in a Garden."