Essentials in Conducting/Chapter 12

CHAPTER XII

The boy choir and its Problems

THE PROBLEMS The two special problems connected with directing a boy choir are:

- Becoming intimately acquainted with the compass, registers, possibilities, and limitations of the boy's voice.

- Finding out how to manage the boys themselves so as to keep them good-natured, well-behaved, interested, and hard at work.

To these two might be added a third namely, the problem of becoming familiar with the liturgy of the particular church in which the choir sings, since male choirs are to be found most often in liturgical churches. But since this will vary widely in the case of different sects, we shall not concern ourselves with it, but will be content with giving a brief discussion of each of the other points.

PECULIARITIES OF THE CHILD VOICEThe child voice is not merely a miniature adult voice, but is an instrument of quite different character. In the first place, it is not nearly so individualistic in timbre as the adult voice, and because of the far greater homogeneity of voice quality that obtains in children's singing, it is much easier to secure blending of tone, the effect being that of one voice rather than of a number of voices in combination. This is a disadvantage from the standpoint of variety of color in producing certain emotional effects, but it is in some ways an advantage in the church service, especially in churches where the ideal is to make the entire procedure as impersonal and formal as possible. In the second place, the child voice is good only in the upper register—the chest tones being throaty, unpleasant, and frequently off pitch. In the third place, the child voice is immature, and his vocal organs are much more likely to be injured by overstraining. When directed by a competent voice trainer, however, the effect of a large group of children singing together is most striking, and their pure, fresh, flutelike tones, combined with the appearance of purity and innocence which they present to the eye, bring many a thrill to the heart and not infrequently a tear to the eye of the worshiper.

THE BOY VOICE IN THE CHURCH CHOIRIn many European churches, and in a considerable number in the United States, it is customary to have boys with unchanged voices sing the soprano part, men with trained falsetto voices (called male altos) taking the alto,[1] while the tenor and bass parts are, of course, sung by men as always. Since the child voice is only useful when the tones are produced with relaxed muscles, and since the resonance cavities have not developed sufficiently to give the voice a great deal of power, it is possible for a few men on each of the lower parts to sing with from twenty to thirty boys on the soprano part. Six basses, four tenors, and four altos will easily balance twenty-five boy sopranos, if all voices are of average power.

THE NECESSITY OF BEING A VOICE TRAINERThere is one difference between the mixed choir of adult voices and the boy choir that should be noted at the outset by the amateur. It is that, in the former, the choir leader is working with mature men and women, most of whom have probably learned to use their voices as well as they ever will; but in directing a boy choir, the sopranos must be taught not only the actual music to be sung at the church service, but, what is much more difficult, they must be trained in the essentials of correct breathing, tone placement, et cetera, from the ground up. Hence the absolute necessity of the choirmaster being a voice specialist. He need not have a fine solo voice, but he must know the essentials of good singing, and must be able to demonstrate with his own voice what he means by purity of vowel, clearness of enunciation, et cetera. These things are probably always best taught by imitation, even in the case of adults; but when dealing with a crowd of lively American boys, imitation is practically the only method that can be used successfully. We shall not attempt to give information regarding this highly important matter in the present volume, because it is far too complex and difficult to be taken up in anything short of a treatise and because, moreover, the art of singing cannot be taught in a book. The student who is ambitious to become the director of a boy choir is advised, first, to study singing for a period of years, and second, to read several good books upon the training of children's voices. There are a number of books of this character, some of the best ones being included in the reference list in Appendix A (p. 164).

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE VOICES OF BOYS AND GIRLSThe child's larynx grows steadily up to the age of about six but at this time growth ceases, and until puberty the vocal cords, larynx, and throat muscles develop in strength and flexibility, without increasing appreciably in size. This means that from six until the beginning of adolescence the voice maintains approximately the same range, and that this is the time to train it as a child voice.

The question now arises, why not use the girl's voice in choirs as well as the boy's?—and the answer is threefold. In the first place, certain churches have always clung to the idea of the male choir, women being refused any participation in what originally was strictly a priestly office; in the second place, the girl arrives at the age of puberty somewhat earlier than the boy, and since her voice begins to change proportionately sooner, it is not serviceable for so long a period, and is therefore scarcely worth training as a child voice because of the short time during which it can be used in this capacity; and in the third place, the boy's voice is noticeably more brilliant between the ages of seven or eight and thirteen or fourteen, and is therefore actually more useful from the standpoint of both power and timbre. If it were not for such considerations as these, the choir of girls would doubtless be more common than the choir of boys, for girls are much more likely to be tractable at this age, and are in many ways far easier to deal with than boys.

At the age of six, the voices of boys and girls are essentially alike in timbre; but as the boy indulges in more vigorous play and work, and his muscles grow firmer and his whole body sturdier, the voice-producing mechanism too takes on these characteristics, and a group of thirty boys ten or twelve years old will actually produce tones that are considerably more brilliant than those made by a group of thirty girls of similar age.

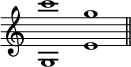

THE COMPASS OF THE CHILD VOICETo the novice in handling children's voices, the statement that the typical voice of boys and girls about ten years of age easily reaches a′′ and frequently b′′ or c′′′ will at first seem unbelievable.

It is the head register, or thin voice, that produces the pure, flutelike tones which are the essential charm of a boy choir, and if chest tones are to be employed at all, they must be made as nearly as possible as are the head tones, thus causing the voice to produce an approximately uniform timbre in the entire scale. This may be accomplished with a fair degree of ease by a strict adherence to the three principles of procedure mentioned in the above paragraph. In fact these three things are almost the beginning, middle, and end of child-voice training, and since they thus form the sine qua non of effective boy-choir singing, we shall emphasize them through reiteration.

- The singing must be soft until the child has learned to produce tone correctly as a habit.

- Downward vocalization should be employed in the early stages, so as to insure the use of the head voice.

- The music should be high in range, in order that the child may be given as favorable an opportunity as possible of producing his best tones.

When these principles are introduced in either a boy choir or a public school system, the effect will at first be disappointing, for the tone produced by the boy's head voice is so small and seems so insignificant as compared with the chest voice which he has probably been using, that he is apt to resent the instruction, and perhaps to feel that you are trying to make a baby, or worse yet, a girl, out of him! But he must be encouraged to persist, and after a few weeks or months of practice, the improvement in his singing will be so patent that there will probably be no further trouble.

THE LIFE OF THE BOY VOICEBoys are admitted to male choirs at from seven or eight to ten or twelve years of age, but are often required to undergo a course of training lasting a year or more before being permitted to sing with the choir in public. For this reason, if for no other, the director of a boy choir must be a thoroughly qualified voice trainer. He, of course, takes no voice that is not reasonably good to start with, but after admitting a boy with a naturally good vocal organ it is his task so to train that voice as to enable it to withstand several hours of singing each day without injury and to produce tones of maximal beauty as a matter of habit. But if the choir leader is not a thoroughly qualified vocal instructor, or if he has erroneous ideals of what boy-voice tone should be, the result is frequently that the voice is overstrained and perhaps ruined; or else the singing is of an insipid, lifeless, "hooty" character, making one feel that an adult mixed choir is infinitely preferable to a boy choir.[2]

Adolescence begins at the age of thirteen or fourteen in boys, and with the growth of the rest of the body at this time, the vocal organs also resume their increase in size, the result being not only longer vocal cords and a correspondingly lower range of voice, but an absolute breaking down of the habits of singing that have been established, and frequently a temporary but almost total loss of control of the vocal organs. These changes sometimes take place as early as the thirteenth year, but on the other hand are frequently not noticeable until the boy is fifteen or sixteen, and there are on record instances of boys singing soprano in choirs until seventeen or even eighteen. The loss of control that accompanies the change of voice (with which we are all familiar because of having heard the queer alternations of squeaking and grumbling in which the adolescent boy so frequently indulges), is due to the fact that the larynx, vocal cords, et cetera, increase in size more rapidly than the muscles develop strength to manipulate them, and this rapid increase in the size of the parts (in boys a practical doubling in the length of the vocal cords) makes it incumbent upon the choir trainer to use extreme caution in handling the voices at this time, just as the employer of adolescent boys must use great care in setting them at any sort of a task involving heavy lifting or other kinds of strain. In the public schools, where no child is asked to sing more than ten or twelve minutes a day, no harm is likely to result; but in a choir which rehearses from one to two hours each day and frequently sings at a public service besides, it seems to be the consensus of opinion that the boy is taking a grave risk in continuing to sing while his voice is changing.[3] He is usually able to sing the high tones for a considerable period after the low ones begin to develop; but to continue singing the high tones is always attended with considerable danger, and many a voice has undoubtedly been ruined for after use by singing at this time. The reason for encouraging the boy to keep on singing is, of course, that the choirmaster, having trained a voice for a number of years, dislikes losing it when it is at the very acme of brilliancy. For this feeling he can hardly be blamed, for the most important condition of successful work by a male choir is probably permanency of membership; and the leader must exercise every wile to keep the boys in, once they have become useful members of the organization. But in justice to the boy's future, he ought probably in most cases to be dismissed from the choir when his voice begins to change.

Let us now summarize the advice given up to this point before going on to the consideration of our second problem:

- Have the boys sing in high range most of the time. The actual compass of the average choir boy's voice is probably g–c′′′ but his best tones will be between e′ and g′′. An occasional a′′ or b′′ or a d′ or c′ will do no harm, but the voice must not remain outside of the range e′–g′′ for long at a time.

- Insist upon soft singing until correct habits are established. There is a vast difference of opinion as to what soft singing means, and we have no means of making the point clear except to say that at the outset of his career the boy can scarcely sing too softly. Later on, after correct habits are formed, the singing may, of course, be louder, but it should at no time be so loud as to sound strained.

- Train the voice downward for some time before attempting upward vocalization.

- Dismiss the boy from the choir when his voice begins to change, even if you need him and if he needs the money which he receives for singing.

THE BOY HIMSELFThe second special problem mentioned at the beginning of this chapter is the management of the boys owning the voices which we have just been discussing; and this part of the choirmaster's task is considerably more complex, less amenable to codification, and requires infinitely more art for its successful prosecution. One may predict with reasonable certainty what a typical boy-voice will do as the result of certain treatment; but the wisest person can not foresee what the result will be when the boy himself is subjected to any specified kind of handling. As a matter of fact, there is no such thing as a typical boy, and even if there were, our knowledge of boy nature in general has been, at least up to comparatively recent times, so slight that it has been impossible to give directions as to his management.

HOW TO HANDLE BOYSIn general, that choir director will succeed best in keeping his boys in the choir and in getting them to do good work, who, other things being equal, keeps on the best terms with them personally. Our advice is, therefore, that the prospective director of a choir of boys find out just as much as possible about the likes and dislikes, the predilections and the prejudices of pre-adolescent boys, and especially that he investigate ways and means of getting on good terms with them. He will find that most boys are intensely active at this stage, for their bodies are not growing very much, and there is therefore a large amount of superfluous energy. This activity on their part is perfectly natural and indeed wholly commendable; and yet it will be very likely to get the boy into trouble unless some one is at hand to guide his energy into useful channels. This does not necessarily mean making him do things that he does not like to do; on the contrary, it frequently involves helping him to do better, something that he already has a taste for doing. Space does not permit details; but if the reader will investigate the Boy Scout movement, the supervised playground idea, and the development of school athletics, as well as the introduction of manual training of various sorts, trips to museums of natural history, zoölogical and botanical gardens, et cetera, school "hikes" and other excursions, and similar activities that now constitute a part of the regular school work in many of our modern educational institutions, he will find innumerable applications of the idea that we are presenting; and he will perhaps be surprised to discover that the boy of today likes to go to school; that he applies at home many of the things that he learns there, and that he frequently regards some teacher as his best friend instead of as an arch enemy, as formerly. These desirable changes have not taken place in all schools by any means, but the results of their introduction have been so significant that a constantly increasing number of schools are adopting them; and public school education is to mean infinitely more in the future than it has in the past because we are seeing the necessity of looking at things through the eyes of the pupil, and especially from the standpoint of his life outside of and after leaving the school. Let the choir trainer learn a lesson from the public school teacher, and let him not consider the boy to be vicious just because he is lively, and let him not try to repress the activity but rather let him train it into useful channels. Above all, let him not fail to take into consideration the boy's viewpoint, always treating his singers in such a way that they will feel that he is "playing fair." It has been found that if boys are given a large share in their own government, they are not only far easier to manage at the time, but grow enormously in maturity of social ideals, and are apt to become much more useful citizens because of such growth. Placing responsibility upon the boys involves trusting them, of course, but it has been found that when the matter has been presented fairly and supervised skilfully, they have always risen to the responsibility placed upon their shoulders. We therefore recommend that self-government be inaugurated in the boy choir, that the boys be allowed to elect officers out of their own ranks, and that the rules and regulations be worked out largely by the members themselves with a minimum of assistance from the choirmaster.

Let us not make the serious mistake of supposing that in order to get on the good side of boys we must make their work easy. Football is not easy, but it is extremely popular! It is the motive rather than the intrinsic difficulty of the task that makes the difference. The thing needed by the choir director is a combination of firmness (but not crossness) with the play spirit. Let him give definite directions, and let these directions be given with such decision that there will never be any doubt as to whether they are to be obeyed; but let him always treat the boys courteously and pleasantly, and let him always convey the idea that he is not only fair in his attitude toward them, but that he is attempting to be friendly as well.

Work the boys hard for a half hour or so, therefore, and then stop for five minutes and join them in a game of leapfrog, if that is the order of the day. If they invite you to go with them on a hike or picnic, refuse at your peril; and if you happen to be out on the ball ground when one side is short a player, do not be afraid of losing your dignity, but jump at the chance of taking a hand in the game. Some one has said that "familiarity breeds contempt, only if one of the persons be contemptible," and this dictum might well be applied to the management of the boy choir. On the other hand, it is absolutely necessary to maintain discipline in the choir rehearsal, and it is also necessary to arouse in the boys a mental attitude that will cause them to do efficient work and to conduct themselves in a quiet and reverent manner during the church service; hence the necessity for rules and regulations and for punishments of various kinds. But the two things that we have been outlining are entirely compatible, and the choir director who plays with the boys and is hailed by them as a good fellow will on the whole have far less trouble than he who holds himself aloof and tries to reign as a despot over his little kingdom.

REMUNERATION ET CETERAIn conclusion, a word should perhaps be added about various plans of remunerating the boys for their singing. In some large churches and cathedrals a choir-school is maintained and the boys receive food, clothing, shelter, and education in return for their services; but this entails a very heavy expense, and in most smaller churches the boys are paid a certain amount for each rehearsal and service, or possibly a lump sum per week. The amount received by each boy depends upon his voice, his experience, his attitude toward the work, et cetera, in other words, upon his usefulness as a member of the choir. Attempts have often been made to organize a boy choir on the volunteer basis, but this plan has not usually proved to be successful, and is not advocated.

When the boys live in their own homes and there are Sunday services only, the usual plan is to have them meet for about two rehearsals each week by themselves, with a third rehearsal for the full choir. Often the men have a separate practice also, especially if they are not good readers.

If the organization is to be permanent, it will be necessary to be constantly on the lookout for new voices, these being trained partly by themselves and partly by singing with the others at the rehearsals through the period of weeks or months before they are permitted to take part in the public services. In this way the changing voices that drop out are constantly being replaced by newly trained younger boys, and the number in the chorus is kept fairly constant.

- ↑ In many male choirs the alto part is sung by boys; but this does not result in a fine blending of parts, because of the fact, as already noted in the above paragraph, that the boy's voice is good only in its upper register. It may be of interest to the reader to know that in places where there are no adult male altos these voices may be trained with comparative ease. All that is needed is a baritone or bass who has no particular ambitions in the direction of solo singing (the extensive use of the falsetto voice is detrimental to the lower tones); who is a good reader; and who is willing to vocalize in his falsetto voice a half hour a day for a few months. The chief obstacle that is likely to be encountered in training male altos is the fact that the men are apt to regard falsetto singing as effeminate.

- ↑ Even when an ideal type of tone is secured, there is considerable difference of opinion as to whether the boy soprano is, all in all, as effective as the adult female voice. Many consider that the child is incapable of expressing a sufficient variety of emotions because of his lack of experience with life, und that the boy-soprano voico is therefore unsuitced to the task assigned it, especially when the modern conception of religion is taken into consideration. But to settle this controversy is no part of our task, hence we shall not even express an opinion upon the matter.

- ↑ Browne and Behnke, in The Child's Voice, p. 75, state in reply to a questionnaire sent out to a large number of choir trainers, singers, et cetera, that seventy-nine persons out of one hundred fifty-two stated positively that singing through the period of puberty "causes certain injury, deterioration, or ruin to the after voice." In the same book are found also (pp. 85 to 90) a series of extremely interesting comments on the choirmaster's temptation to use a voice after it begins to change.