Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes/Introductory Lessons

LESSON I.

WHAT GEOGRAPHY MEANS.

1. Homes.—Some boys and girls have homes in the country. The two boys that you see in the picture live in a pleasant valley near the mountains. These boys see around them fields of wheat and corn. They see a wagon drawn by oxen, carrying wheat to the barns. A man is driving a flock of sheep along the road, and a train of cars is approaching the village. Far away in the distance, they see the high mountains.

Some boys and girls have homes in cities. They may see long streets like the one in the left-hand picture, and other streets going in every direction. On some of these streets there are stores; on others there are homes where people live; passing through the streets are street cars, wagons, and carriages, and on the sidewalks busy people are going and coming.

Some boys and girls have homes near the seashore. They may see the blue waters and the waves dashing against the rocks or rolling up on the sandy beach.

Children living in different places may see very different things. But all these things are the earth. The mountains, the sea, the fields, the gardens, the woods, the dusty roads, and streets, the land on which our homes are built, are all parts of the earth. 2. The Earth is very large. Near our homes we can see only a small part of it. When we go away from our homes in any direction, we see other parts where other people live. These people may be very different from us, and their homes quite unlike ours. Everywhere we find them doing some kind of work, which may also be quite different from the work that we do.

The story about the different people that live on the earth, about their homes and what they do, is called geography.

For Recitation.—What can you see in the first picture? in the picture on the left hand? In the picture on the right hand? Have you ever visited the country, the city, or the seashore? What were the people doing there? What kinds of houses did you see? What plants or animals? Can you think of some place that you would like to visit and learn about? What must you study in order to learn about these places?

LESSON II.

DIRECTION.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Impress carefully upon the minds of pupils the necessity of fixed, unchangeable points of direction, which can be understood by everybody.

Ask the pupils to point to the right; to the left; before them; behind them. Then show that all these directions are variable in their meaning. Thus: Who sits on your right hand? On your left? In front of you? Behind you? Turn round. Who is on your right now? Behind you? Before? On your left? Point to the right. Turn round. Point to the right now. Does pointing to the right, to the left, in front, or behind always give you the same direction?

This photograph was taken at noon; the car tracks run north and south.

Notice that at noon shadows always fall toward the north.

Having shown the indefiniteness of such expressions for directions as right, left, before, behind, pass on to a thorough drill on the fixed directions. Let this be repeated daily, until every pupil can point, without hesitation, to the four principal directions, and to the four half-way directions.

Ask on which side of the schoolroom the sun rises. On which side it sets. Which is the east side of the pupils' desks? Which the west? The north? The south? Who sits to the east, west, north, and south of them? In what direction the teacher's desk is? In what directions the children go from school to their homes; and in what directions they come from their homes to school.

Let them tell in what directions the most familiar objects, such as the church, the post-office, or the city hall, are from their school and homes.

Vary the drill and exercises. In taking up the drill work in connection with different lessons, avoid as far as possible asking the questions in exactly the same words.

1. What Direction Means.—Suppose you are going for the first time to visit the home of a friend. One question that you will ask before starting will be, "Which is the way?" If you do not know the way you may be lost.

Now the way to a place is called direction.

And when we are learning about any people or places, one of the things we wish to know is, in what direction they are from us.

We may learn about direction from the sun. The part of the sky where it rises is called the east. So if, some bright morning, we are walking with the sun shining in our faces, we cannot help knowing that we are going toward the east.

The part of the sky where the sun sets is called the west. The west is just opposite the east. If we walk so that the setting sun shines in our faces, we are going toward the west.

If we walk with the morning sun upon our right sides, we shall be going toward the north. If we should meet a boy walking in the opposite way, he would be going toward the south.

The sun, we see, helps us to learn the principal directions, north, south, east and west. These are what we call fixed points.

If the place to which we are going lies half-way between the north and east, its direction is northeast. If it is half-way between north and west, the direction is northwest. If the place is half-way between south and east, the direction is southeast. And if it is half-way between south and west, the direction is southwest.

From what we have now learned we see that when the sun shines it is easy to tell in what direction we are going. But there is something that shows direction even better than the sun.

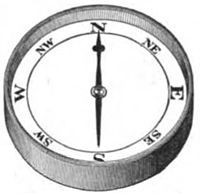

Sometimes people are days and days at sea without seeing the land, and with nothing but sky above them and water all around. Often the sky is covered with clouds, and the sun cannot be seen. How do they know which way to go? They use what is called the compass. In it there is a little needle made of steel that always points toward the north.

With a compass, therefore, we can always tell which way is north. And if we know where north is, we can also tell where the south, the east and the west are.

The Indians and hunters who catch animals for their fur live a great deal in the forests. Often there are no roads to guide them. Sometimes it is very cloudy, and they cannot see the sun. They are said to have a very curious way of finding out where the north is.

Moss grows best in shady places, and generally grows thickest on the north side of the trunks of trees, because the sun does not shine much on that side.

The hunters and Indians, therefore, look to see which side of the tree is covered with moss. They know that the mossy side is the north side. Moss is to them as good a friend as the compass is to the sailor.

At night it is easy to find one's way if the stars can be seen. There is one star which is always in the north. We can see it in the picture.

The single star is called the North Star because it is always in the north. We find it by the help of two bright stars in the Great Dipper. They are called the Pointers.

For Recitation.—What do you mean by direction? What are the chief directions? How can you tell where the east is? Where is the west? Where is the north? Where is the south? What other points of direction are often spoken of? What shows direction better than anything else?

LESSON III.

DISTANCE.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Have pupils, using twelve-inch rulers, draw lines on the board one foot long; two feet long; one yard long, etc. Draw in various directions lines of different lengths, and ask how long each is. Test the correctness of answers with the ruler. Have children draw lines by guess, and test the accuracy of their guesses.

Have the pupils learn what two places in the neighborhood are about one mile apart; in a city, how many blocks there are to a mile. Have pupils tell about their walks or drives, noting distance and time.

1. What we Mean by Distance.—It is not easy to find a place if we know only in what direction it is from us. We should know also how far away it is, or the distance we shall have to go before reaching it.

If we know only that the house of a friend is east of ours, we cannot tell just where it is. But if we know that it is east of ours, and also how far east, then we can tell very nearly where it is.

The honey-bee knows exactly in what direction it must fly when it wishes to go home, and it knows also the distance, or just how far it must fly.

The mother bird that has her little ones in a nest in the tree, knows not only in what direction she must fly, but how far she must fly, so as to get back to the nest.

The bees and birds all know direction and distance by instinct. We have to learn.

We have already seen how we learn about direction. Let us now see how we learn about distance.

View of a broad valley in Maryland. Notice how distance affects the size and appearance of objects.

Very often we do not need to be exact. It is enough to know that a place is "very far off" or "very near." But sometimes we must know just what the distance is. To find out this we measure.

How do we measure? We measure with foot rules and yard sticks and tape measures. You know how long an inch is. Twelve inches are called a foot. Three feet make the measure that we call a yard. Five and a half yards make what we call a rod.

With these measures we can easily find out short distances We can see how long the schoolroom is, or how long and how wide the playground is.

But for very long distances we must have very long measures; and so we call the distance of 320 rods one mile. We can walk a mile in about twenty-five or thirty minutes. So if it takes us half an hour to walk from our home to school, the distance is about a mile.

For Recitation.—If we wish to go to any place, what should we know besides the direction? What is meant by the distance between two places? How do you measure short distances?

| Pupils should be required to memorize the following table: | |

| 12 inches are one foot. | 5½ yards are one rod. |

| 3 feet " " yard. | 320 rods " " mile. |

LESSON IV.

MORE ABOUT DIRECTION AND DISTANCE.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Draw on the board an oblong like the teacher's desk. Let the children place objects on the desk while you put marks on the plan to represent the positions of these objects. Put marks on the plan and have pupils put objects on corresponding places on the desk. Do the same with pupils' own desks.

Draw a plan of the room on the board. Make the top north. Have pupils stand in various places, and mark these places on the plan; then put marks on the plan; and let pupils stand at places in the room corresponding to these marks.

Measure the room with a tape measure, and draw on the board a plan on the scale of an inch to a foot. Have pupils draw on paper to a smaller scale. Measure the school yard and places in the neighborhood. Make plans and maps of these places.

1. Pictures.—We have now been talking and thinking a great deal about direction and distance. In this lesson we will try to understand how they are shown to the eye. To show them to the eye we use what we call plans, or maps. But what are plans, or maps?

We all know what pictures are. Here we see the picture of a schoolroom.

Picture of a city schoolroom.

It almost seems as if we were in it. There are desks and blackboards, pupils, teacher, teacher's table, pictures, etc., all looking just like the things themselves.

Pictures, then, are drawings that show how things look.

2. Plans, or Maps, are different. They are drawings that show where things are. They tell in what direction things are from one another, and how far apart they are.

Here we have a plan of the schoolroom, the picture of which is shown above.

Plan of the schoolroom in the picture.

Let us make a plan of our own schoolroom on the blackboard.

The first thing is to represent the sides. Suppose we measure them. We can see that they cannot be drawn on the blackboard as long as they really are.

So we will let one inch on the blackboard represent one foot. Then we will draw all the sides so many inches long, instead of so many feet long.

Now how shall we show directions in our plan? We cannot show them exactly as they are; but we will call the top of the plan north, the right hand east, the bottom south, and the left hand west.

We have now drawn the schoolroom floor. But there is nothing on it. That will never do. So we will make some little marks that shall show just where the desks and chairs are. Then we shall have a plan, or map, of the schoolroom floor and of the things, upon it.

Our plan is a great deal smaller than the floor really is, but all the parts are made smaller alike, or in proportion. The plan is said to be drawn on a scale of 1 inch to 1 foot, which means that every inch on the plan stands for 1 foot.

Now what does the plan show? It shows just where everything is, in what direction things are from one another, and how far apart they are.

We can see that the door is on the north side of the room, that the teacher's desk is on the west side, and that the windows are on the south. We can see in what direction each pupil is from every other.

Then, again, we can tell how far each thing is from every other. If it is twenty inches on the plan from one boy's desk to the door, you know that that boy has to walk twenty feet to reach the door when he is going home, because every inch stands for one foot.

3. Picture of a Village.—Here is a picture of a village with its streets, its railroad station, its factory, its churches and its homes. Does it not look just like a village? You can see the train coming into the station, and the stream which flows near by. Find three bridges across the stream. Find the farmhouse in the country north of the village.

Picture of a village.

4. Plan, or Map, of a Village.—Here we have a plan, or map, of the same village. It does not look like a village, but, like the plan of the schoolroom, it shows the direction and exact distance of points from each other.

Map of the same village. Find objects shown in the picture.

5. Larger Maps.—Now as we make maps of villages, so we make maps of counties, states, and whole countries. In some maps, as we shall soon learn, half of the earth is shown at once.

The scale of such a map will be very small. An inch may represent more than a thousand miles.

For Recitation.—What do plans, or maps, show? How much land can be shown on a map?

LESSON V.

THE EARTH.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Make balls of clay. Stick a hat pin through the center of each, ball, and measure the distance through the balls. Do this from several directions. Ask if the measurements are the same. Should they be? Teach the word diameter.

Cut each ball into halves. What shape is the cut surface of each half? Measure the distance around the edge with a string. Put the halves together and halve again in another plane. Ask if these measurements are the same. Should they be? Teach the words circumference, equator, and poles.

1. Shape of the Earth.—In studying geography we shall learn a great many strange things. One of the strangest things is what we learn about the shape of the earth.

Suppose the earth were flat, and we were to travel on and on in one direction without turning, should we ever come back to the same place from which we started? Of course we should not. If we traveled long enough we should come to the edge of the earth. We should be like an ant walking on a table. If the ant keeps on in one direction all the time, it will reach the edge of the table.

But if the ant walks upon an orange and always goes in the same direction, it will at last come to the place from which it started. This is because the orange is round.

If people travel on the earth, always keeping in one direction, like the ant on the orange, they never come to any edge. They arrive at last at the place from which they set out. So we know that the earth is round like a ball or an orange.

Ships seen from the shore.

When the author of this little book was a boy he started from New York in a ship, and traveled for many months, never turning back, until at last he came to New York again. He had gone round the earth. The earth does not seem round to us. The fields and the village, or the city where we live, may be flat. Some places look as flat as a floor. But still the earth is round.

Can we suppose that the little ant on the orange thinks that the orange is round? If he thinks at all, he must think it is flat.

We are so large that we see a large part of the orange at once. Hence we can see that it is round. The small ant sees only a small part of the orange at once, and that part seems flat.

If we could stand off and look at the earth as we look at the orange, then we should see that it is round. But we cannot get far enough from the earth to do this; we can see only a very small part of it at one time. This is the reason that it seems flat to us.

The Earth as it would look if we could see it from the moon.

2. Size of the Earth.—Suppose a carrier dove should fly round the earth. A swift carrier dove can fly 100 miles an hour. If it was to fly at that rate, without ever stopping, it would be more than ten days in going round the earth.

If a man could walk round the earth, and went 50 miles a day, the trip would take him more than sixteen months.

What a big ball the earth must be! We know about how much a mile is. The distance round the earth is 25,000 miles. This distance is called the circumference of the earth. The distance through the earth is about 8,000 miles. This distance is called the diameter of the earth.

The distance through the earth is a little greater at the equator than it is at the poles. If you press an orange between your thumb and linger and flatten it a little, it will have about the same shape as the earth.

For Recitation.—What is the shape of the earth? How do we know this? Why does the earth seem flat to us? How far is it round the earth? How far is it through the earth?

LESSON VI.

THE SURFACE OF THE EARTH.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Teach the word surface. Touch the surface of the globe; of the desk. Teach that one is a flat and the other a curved surface. In the same way teach the word interior.

Show the pupils how the waves dashing against the rocky coast might tear it down, and by pounding the torn pieces and rolling them about might grind them down to pebbles and sand.

1. Land.—The outside of the earth is called its surface. One part of the surface is solid, or hard. This is called the land.

We live on the land, and build our houses and towns and cities upon it. Trees and other plants grow on the land, and animals live on it.

2. Water.—But there is a large part of the surface of the earth which is water. Most of us have seen a pond, and we all know what a pond is. Now suppose a pond were made ever so large, hundreds and thousands of miles across, instead of a few yards. There is a pond as large as that. It is called the sea.

How large do you think it is? A boat can sail across a small pond in a few minutes, but it takes a sailing vessel about fifty days to sail across some parts of the sea. Think of being on the water seven weeks without seeing land!

We can see in the picture above that the water surface is very much larger than the land surface. There is nearly three times as much water as land.

Under the water is land which is much like other land except that the water covers it. Strange plants grow on it. There are no daisies or buttercups, but there are seaweeds of beautiful colors, purple and yellow and red and green. The fishes, you see, have their gardens as well as we.

A view of Cornwall, England, where the land and the sea meet. The sea washes against the cliff and wears it away.

It may seem strange that the fishes should have so much more room to live in than man and the other animals. But we shall see, when we know more about geography, that man and the lower animals that are on the land could not live at all if it were not for the great sea. The plants would have no rain. They would all die, and there would be nothing for us and the lower animals to eat.

3. Air.—Over all the land surface and over all the water surface is something that we call air. It is just as much a part of the earth as the land and the water. We live in this air much as fish live in the water. It is all around us, but it is so thin and clear that we cannot see it. When we look up, the blue that we see and call the sky, is really air.

When air moves past us wo can feel it, and then we call it a breeze or wind.

The clouds are floating in the air. Anything that is as light as air will float in it. A balloon rises and floats because it is filled with something lighter than air.

Below the land surface and below the water that fills the low places in the land, is rock, and we believe that far down in the center this rock is red-hot all the time; but the center is so far below the surface that no one has ever been able to get far enough into the earth to find out whether our belief is correct.

For Recitation.—Into what is the surface of the earth divided? How much of the earth's surface is land? How much of it is water?

LESSON VII.

THE LAND.

Preparatory Oral Work.—On a sand board, or big table, or tin tray, painted blue, if possible, to represent water, make roughly, with wet sand, shapes representing the land forms. Develop therefrom the meanings of the terms coast, continent, island, peninsula, isthmus, cape, and teach the terms. Who has seen an island? a peninsula? a cape? an isthmus?

Turn to the relief map on page 35. Find a peninsula; an isthmus; an island.

1. We have now learned that the surface of the earth is partly land and partly water.

Both the land and the water are divided into parts of bodies of different sizes and shapes.

2. Continents.—The largest parts or divisions of the land are called con'-ti-nents. Notice two of them in the picture on page 9.

We can travel on them for hundreds and even thousands of miles without ever reaching the sea. It takes a railway train nearly a week to go across the continent on which we live. 3. Islands.—Parts of the land smaller than continents, and entirely surrounded by water, are called islands.

All the islands have never been counted, because there are so many. Some of them are very large, others so small that they look on the map like specks. Some contain a great many inhabitants; others have no one living upon them.

Perhaps the most curious of all are the Coral Islands. Most of them are found in the Pacific ocean. We shall learn more about these islands by and by.

4. Other Forms of Land.—The edges of the land are often jagged, as shown in the picture.

A peninsula on the coast of Massachusetts. Find a cape and an isthmus on the peninsula.

Some parts stretch far out into the sea, and are nearly surrounded by water. These are called pen-in'-su-las. The word peninsula means almost an island.

A narrow strip of land that connects two large bodies of land is called an isthmus.

Points of land jutting out into the water are called capes.

Find a peninsula on map, page 35. Find also an isthmus. How many capes can you find?

A small island on the coast of Maine. Notice the hotel, the steamer just leaving, and the boat sailing around the island.

For Recitation.—What are the continents? What is an island? What is a peninsula? What is an isthmus? What is a cape?

LESSON VIII.

MORE ABOUT THE LAND.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Teach the word slope. Teach the word plain. Teach the word hill. Teach the word valley.

Have pupils make these forms in sand or clay. Then let them make a mountain, a chain or range of mountains, a ridge, a peak; use pictures and stories to develop the ideas.

1. Heights of Land.—The playground is level, or nearly level. Let us imagine it stretched out for miles on every side. Nearly level land like this would be called a plain. On very large plains we may travel for days and days together, and see only the blue sky above us and level land all around.

Some large plains are called prairies. They are often covered with long grass and beautiful flowers. Thousands of buffaloes used to live upon them. Many of the prairies are now plowed and used as corn and wheat fields.

A plain lying along the seacoast is called a coastal plain. A high plain is called a plateau.

Now imagine a great plain covered with sand, rocks and stones—not a single flower to be seen, not even a blade of grass, for hundreds of miles. Such land is called a 'desert.

In a desert we find here and there a patch of ground where water bubbles up. Here trees grow and flowers bloom. Such a spot is called an o'-a-sis.

Instead of being level, like plains, the land in some places slopes up and up until it is higher than a house, or the tallest tree. Such land is called a hill.

A very high hill is called a mountain. Some mountains are so high and so hard to climb that no one has ever been to the top of them.

A range of mountains in the Alps in Europe. In the narrow valley between the mountains many people have homes.

It is very cold at the tops of high mountains, and many of them are always covered with snow.

Some mountains slope down on all sides, but generally mountains extend in long lines with slopes on but two sides. Such a line of mountains is called a range or ridge. When several ranges near each other extend in about the same direction they are called a mountain chain.

There is a wonderful kind of mountain that seems to be on fire inside. It is called a volcano. There is a great hole called the crater at the top of it, and out of the hole red-hot cinders and melted stones are sometimes thrown far upward.

The land which lies between mountains or hills is called a valley.

For Recitation.—What is a plain? A prairie? A desert? A hill? A mountain? A volcano? A valley?

LESSON IX.

THE WATER.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Boil some salt water before the class and condense the steam upon a cold plate. Have the children taste the water before boiling, and afterwards taste the drops formed by the condensed vapor. Explain how vapor rises and forms clouds; how clouds are carried over the land; how mountains condense them into rain or into snow; how the rain sinks into the ground and comes out again as springs.

Teach the wearing power of water. The schoolroom yard or a dirt road will teach this. Explain how the mud that a river washes away from the hills is deposited.

1. The Sea.—There are a great many interesting things to learn about the sea. First of all, it is never still. It is always rolling and rocking or dashing its waves into foam on the shore. In storms the waves often drive ships on rocks and wreck them. Another movement of the sea causes it to rise and fall slowly twice in a day. These two movements of the sea are known as tides.

Vesuvius, a volcano in Italy, in eruption, 1906. About 700 feet of the cone of Vesuvius was blown away during this eruption, and several villages were destroyed.

The sea as it rolls up on a flat sandy coast called a beach. Compare with the sea pounding the rocks, on page 10.

Then again the sea is very deep. In some places it is five miles to the bottom. The water of the sea is salt. Sailors take fresh water with them to drink when they go to sea.

Besides being interesting, the sea is useful. It is a great highway. Ships are all the time carrying things across it, from one country to another. If we go into a grocer's store, we see spices for sale. They grew thousands of miles away, and were brought over the sea in ships.

A bay. A breakwater has been built to enclose part of the bay as a harbor for the city.—Nice, France.

2. Divisions of the Sea.—The sea is one sheet of water. A ship can sail all over it. But different parts of it are called by different names. The largest parts or divisions of the sea are called oceans.

There are smaller divisions that are partly shut in by the land. These are called gulfs, bays, and seas. A portion of a bay so nearly enclosed by land that ships can be sheltered in it is called a harbor.

A generally narrow passage of water connecting two larger bodies of water is called a strait.

In some cases bays and straits are caused by the ocean's wearing away the coast. In other cases they are caused by the sinking of a strip of the land, so that the waters of the ocean flow over it.

Some straits are called channels. Wide straits are sometimes called sounds.

3. Water upon the Land.—Besides the water of the sea, there is a great deal of water upon the land. Most of it is fresh.

A mountain watershed. The Blue Ridge in North Carolina. Its slopes carry water from the divide to two different streams.

And yet it all comes out of the salt, salt sea. Let us try to understand this. When it rains or snows the sky is covered, we know, with clouds. Clouds are vapor. They are like the steam which comes out of a kettle or an engine.

The Columbia river, near its source.

The sun is all the time heating the sea and making vapor rise. That vapor forms the clouds. The winds drive the clouds from the sea over the land, and down they come as rain or snow. Put when the vapor rises from the salt water it leaves the salt behind. And so, the rain and snow are fresh. Some of the rain and snow is at once drained off by rivers; some sinks into the ground.

Where streams overflow mud is deposited which builds up a plain, as is seen in this view of the Connecticut river. Scientists call this a flood plain; others call it bottom land.

Fresh water that bubbles out of the ground is called a spring; and yet it is only rain that sank slowly into the ground and comes bubbling out again.

The water from springs may be seen flowing down the hillside and looking like a bright stream of silver. Many little streams unite to make a larger one called a brook, or a still larger one called a creek.

In a dry country, streams cut through their plateaus rapidly, leaving hills whose sides are straight up and down. This is the Green river in Colorado. Compare with Yadkin river.

Now suppose several brooks or creeks come together and make a stream larger yet, what will that be? We call it a river. The beginning of a river is called its source; the end of it is called its mouth. Now let us follow a river that begins among the mountains. Let us go from its source down to its mouth.

The first part of such a river is very rapid. The water dashes down the mountain side. Sometimes it leaps from rock to rock and makes waterfalls.

When it reaches the plateau, it is still very swift. Here, along the bank, we see mills for grinding corn or making cloth. They have wheels which the water turns as it passes on its way to the sea.

The mills need people to work in them, and so there is a village or a town built near by. Many cities have been built on the banks of rivers just because the swiftly running water then could be used to turn mill-wheels. On page 46 is a picture of a New England river and cotton mills built at its falls.

The Yadkin river, North Carolina. Streams cut through the plateau, leaving the Piedmont, or foot hills, as we see them here. In the second cut notice how the land has been cut by streams.

From the plateau, the river comes down to the coastal plain. Here the land has very little slope, and the river flows slowly and becomes so deep that steamboats run on it. At its mouth we find cities called seaports, where ships bring in goods from other countries to be exchanged for goods that come down the river on boats, or over the land on railroads.

Another work that rivers do for us is to drain the surplus water from the land and carry it back to the sea.

A river, the Savannah, flowing through the coastal plain. The seaport is Savannah, Ga. Notice the ships. This plain is made of mud cut away from the plateau, and brought dawn by the river.

Every brook and every creek is made up of water that falls near it, and rivers are made of the water poured into them by brooks and creeks. A river and all the streams that carry their water into it make a river system, and the land from which they drain the water is called the river basin. On page 87 find three great river systems and the basin which each one drains.

Sheets of water surrounded by land are called lakes. Some lakes are called seas. Many rivers rise in lakes.

For Recitation. What are oceans? What is a gulf, bay or sea? What is a strait? What is a spring? What is a river? What is a lake?

LESSON X.

THE EARTH ROTATES—DAY AND NIGHT.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Take an orange or a ball of yarn or clay and put a bat pin through it. Stick a tack or a bit of paper on each globe to represent where we 1ive. Let the pupils perform the experiment with a lamp or candle. Ask: What represents the earth? The axis? The sun? Where is it day? Where is it night? Where do we pretend that you live? Make it midday at that place; evening; midnight; morning; midday again. Let each child observe and record the hour of sunrise, of sunset.

1. What makes day and what makes night? We shall try to learn in this lesson.

Of course we know that it is day when the sun shines upon as. But why is it not always day? What makes the sun set and the light fade? And then, what makes the sun rise again in the morning?

People used to think that the sun really did come up and go down. They thought that it went under the earth at night, and came out again in the morning. They supposed that the rising and setting of the sun were like taking a lighted lamp and carrying it across a table, and then putting it under the table and bringing it out after a while at the opposite side. But we know that all this was a mistake.

2. What really happens? Let us see. Suppose we put an orange or a ball in the sunlight, or in the light of a lamp. Does the light shine all over it? No. Only one-half of it is in the light. The other half is dark. Like the orange or the ball, the earth is in the sunshine; but only one-half of it can be bright at a time. The other half must be in the dark.

Now let us stick a knitting-needle or a sharp piece of wood right through the orange at the place where the stem used to be. Next let us hold the orange in the sunlight or lamplight, and make it turn round upon the knitting-needle. We shall in this way bring the side that was first dark into the light, and the side that was first light into the dark.

The knitting-needle stuck through the orange may be called the axis of the orange. And the orange, when it turns on the needle, is said to turn on its axis.

3. Now the earth turns round from west to east. It is said to rotate, or turn on its axis. Of course, we must not suppose that it really has a rod of iron or anything else stuck through it for an axis. But it turns as if it had.

One thing more we notice about our turning orange. It soon stops if we do not keep on making it turn. But the earth never stops. First one side is in the sunlight and then the other. The bright side has day. The dark side has night.

Whenever it is daylight with us, it is night with the people who live on the other side of the earth. When we are eating our breakfast or hurrying off to school, the children who live on the other side of the earth are getting their supper or going to bed.

We turn the orange round on its knitting-needle in a few seconds. But it takes the earth twentyfour hours to go once round on its axis. This is why we have about twelve hours of sunshine and twelve hours of night.

For Recitation.—How does the earth move? How long does it take to turn round? When do we have daylight? When do we have night? Does the sun really come up every morning and go down every evening? When the sun rises, what is happening? And when the sun sets, what is happening?

LESSON XI.

THE SEASONS.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Use again oranges or balls, hat-pins, and candles. Move the globes around, keeping the north pole always pointing in the same direction, and name the seasons. Then turn the ball on its axis as you carry it around the candle, so as to teach the class how both motions are going on at the same time. Let each pupil make the experiment. Ask who can do this at home to-night.

On the first Monday in each month, at twelve o'clock, measure the length of shadow of a perpendicular pole and record it. Measure the distance that the sun shines into the south window and record it. The shadows will be longest in December and shortest in June.

Notice that the axis of the orange always slants the same way. For this reason at 2 the light shines on the top of the orange; at 4 on the bottom; at 1 and 3 equally on both top and bottom

1. The Earth Revolves.-Besides turning round on its axis, the earth moves in another way. Let us try to understand this movement. Suppose we draw a large chalk ring on the floor, or on the top of a large table, and then put the lighted lamp in the middle of the ring.

Now let us walk round the ring, holding the orange with the knitting-needle through it, so that the light of the lamp shines on it.

What we are now doing with the orange shows what happens to the earth. Nobody marks a ring for the earth with chalk, but still it goes in a ring, round and round the sun, as the orange does round the lamp. Nobody carries it, as we do our orange. It goes of itself, but it never gets tired and never stops.

It is only a few feet round our chalk ring. It is millions of miles round the earth's ring.

It takes us only a minute or two to carry our orange round the lamp. It takes the earth a whole year, all the time from one of our birthdays to another, to revolve around the sun.

1. The Seasons.—Now as the earth moves in its ring round the sun, sometimes our country receives more sunshine and heat, and sometimes less.

At one time the swallows come. The birds build their nests. The people are planting and sowing. It is now not very hot and not very cold. It is spring. The orange at 1 in the picture shows where the earth is in its path at this time.

In a very short time there comes a change. The days grow longer, the weather gets warmer. The trees are full of fruit, the melons are ripe. It is summer. The orange at 2 in the picture shows where the earth is in its path at this time.

Months pass. The leaves turn and begin to fall. The yellow corn is gathered in. Thanksgiving Day comes. It is autumn or fall. The orange at 3 in the picture shows where the earth is in its path at this time.

Again there is a change. The days grow shorter, the weather gets colder. Snow covers the hills; ice covers the ponds. Christmas and Santa Claus come. It is winter. The orange at 4 in the picture shows where the earth is in its path at this time.

These four parts of the year—spring, summer, autumn, and winter—are called the four seasons.

In some countries there are only two seasons, called the wet and the dry. In others there is one long winter with scarcely any summer.

For Recitation.—Besides turning on its axis, how else does the earth move? How long dues it take the earth to go round the sun? What changes in the weather take plaec as we go round the sun? What, then, may we say is caused by the earth's revolving round the sun? How many seasons have we? Have all parts of the earth four seasons?

LESSON XII.

CLIMATE AND ZONES.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Keep on the board a daily record of temperature and rain for two weeks preceding this lesson. Now turn to this record and teach the terms weather and climate. Ask on how many days we have had wet weather; on how many dry weather; whether our climate is wet or dry.

1. Climate.—We have learned that the sun gives us heat and light, and that besides this, it makes the vapor rise from the sea, and so causes the rain to water the earth.

But the sun shines upon the earth in such a way that it warms and waters some parts of it much more than others.

Some parts are very hot; some are bitterly cold; others are sometimes hot and sometimes cold. So, too, some parts of the earth are very rainy; in some there is hardly any rain at all; in others there is neither too much nor too little rain.

The heat or cold, and the moisture or dryness of a country for all the time make up what is called its climate. When we speak of these for a short time, as a day, or a week, we use the word weather.

A country that has much more hot weather than cold during the year has a hot climate; one that has cold weather the greater part of the year has a cold climate; and a country in which the hot and cold parts of the year are nearly equal has a temperate climate. The climate, again, may be moist or it may be dry.

2. Zones.—Look at the picture. The red belt shows that part of the earth which receives the most heat from the sun, and in which the most rain falls. This is called the Torrid or hot zone. Zone means belt.

Across the middle of the picture is a line which divides it exactly into halves. We imagine such a line to go all round the earth. It is called the equator. The Torrid zone lies on both sides of it, and the sun is always shining straight down on some part of this zone.

The white belts represent the parts of the earth which receive little heat, and where the air is always cold. These are called the Frigid or frozen zones.

We see at the top and bottom of the picture two little while dots. These show the points of the earth's surface that are farthest away from the equator. We call these points the north pole and the south pole. The Frigid zones lie around them. There is at least one whole day in each year during which the sun does not shine upon any part of these zones.

The yellow belts show where there is a summer and a wintcr, and where both the heat and rain are less than in the Torrid zone. These are the Temperate or mild zones. Here the sun never shines straight down, but it never fails to shine during some part of every day.

There are two Frigid zones and two Temperate zones. These are known as the North Frigid zone and the South Frigid zone, and the North Temperate zone and the South Temperate zone.

We must go quite far north or south of the place where two zones join before we notice that the zone we are in differs from that which we left. However, if we should climb up a high mountain, in either of the Termperate zones or even in the Torrid zone, we would notice that the climate soon becomes colder and colder the farther we go up above the lowlands.

The climate of a country depends chiefly on its being in one or another of these zones.

In the Frigid zones we should see mountains of ice and endless fields of snow.

The people live in huts of snow and ice. They dress in fur and even then can hardly keep warm.

If a person should go from his snow hut in the Frigid zone to the Torrid, he would find his fur clothing too hot to wear. He would want the thinnest clothing to he found.

In the Torrid zone there is no winter.

The two Temperate zones are not so hot as the Torrid zone, nor so bitterly cold as the Frigid. They are the pleasantest parts of the world.

Our home is in the North Temperate zone.

Many other things change the climate of a place. High mountains, even in the Torrid zone, give a temperate climate to places half-way up their sides, and give a frigid climate at their snow-covered tops. If warm, moist winds constantly blow over a country, they give it a mild climate.

For Recitation.—What does the sun do for the earth? What is meant by the climate of a country? What part of the earth has the most heat and rain? What are the coldest parts of the earth? What kind of climate do you find in the temperate zones? In which zone do you live? In what direction would you travel to reach the Torrid zone? The South Temperate? The North Frigid?

LESSON XIII.

PLANTS.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Talk to class about the care and cultivation of plants. Why are some plants taken up when cold weather comes and put in the house? How does frost affect plants? What plants can live out of doors all winter? Teach the reason for the cultivation of different plants—for the root, seed, leaf, blossom, etc.

What Plants Are.—What is the use of the earth's being warmed by the great sun, and watered by the rain and dew? Let us see. Everything that grows out of the earth is called a plant, and all plants need water to drink, and sunshine to keep them warm. Some need a great deal of water and warmth; others want only a little.

Plants cannot grow without heat and moisture. Different plants belong to different zones.

In the Frigid zones the winters are long and very cold with little light. Hardly anything grows here except mosses and a few low-growing plants that flourish during the short summer. The Frigid zones may be called the treeless belts.

Let us leave them and visit the Temperate zones. Here we shall find more heat, and more light, and plenty of rain and dew. And so we find here, too, a great many plants.

In each of the Temperate zones that part near the frigid is still very cold, and we call it the cold belt. Fir trees and oats grow here. In the middle belt of the Temperate zones we find the really temperate climate. Wheat, corn, and cotton grow in the fields. There are forests of oak, maple, and pine, and orchards of pear, apple, and peach trees. Nearer the Torrid zone the climate is very warm, and we call this the warm belt of the Temperate zones. Here rice is the principal grain, and the tea-plant, sugar-cane, and orange trees grow.

In the Torrid zone there are more heat and more rain than anywhere else. So here we find the greatest number of plants. There are forests of India rubber trees, groves of palms and jungles of bamboos. The delicious banana and pineapple are among the fruits of this zone. In it the coffee-plant and sugar-cane have their home, and the largest and most beautiful flowers grow. The different plants of a country make up what we call its vegetation. Did you ever think how useful plants are to us? What should we do without corn and wheat to eat, tea and coffee to drink, sugar to make things sweet, timber with which to build our houses, and cotton to clothe our bodies?

For Recitation.—What is a plant? What do plants need? Why do we find the fewest plants in the Frigid zone? What kind of plants grow in the Frigid zone? Name some of the plants of the temperate zones? Where do we find the greatest number of plants, and why? Name some of the plants of the Torrid zone.

LESSON XIV.

ANIMALS.

Preparatory Oral Work.}—Get pupils to talk about animals that they have seen. Which work for man? Which furnish food for us? Which furnish clothing for us? What wild animals have you seen? What did they eat?

Whatever lives, eats, feels, and can move from place to place is called an animal. There are many kinds of animals, and they are very different from one another.

Some animals, like some plants, need a hot climate; others need a cold climate. Different animals belong to different zones.

Very few animals belong to the Frigid zone, but there are some that can live only there.

The walrus and seal find no place so nice as the icy seas of the Frigid zone. They must bathe every day in water so cold that it would freeze us.

In the same cold zone live the huge white bear and the reindeer, an animal that is fond of hunting underneath the snow for his dinner of moss.

In the Temperate zones we find the greatest number of animals that are useful to man. Most of these animals live on plants. The horse, the ox, the cow, the sheep, and the goat are called domestic, because they have been tamed and make their home with man.

Among wild animals are the grizzly bear, the wolf, and the kangaroo.

In the Torrid zone there are more wild animals than anywhere else. That zone is the home of some of the largest, the fiercest, and the most beautiful animals.

In the woods there are huge snakes, lions, and tigers. Monkeys are jumping from tree to tree. Blue and green parrots are screaming from the tree-tops, and scarlet flamingoes are wading in the pools. In the Torrid zone we can ride on the back of an elephant and hunt the tiger.

A growing corn plant: the dark layer at the top is soil; next below comes gravel, then clay, gravel again, and, finally, hard rock.

The water at the bottom of the deeper parts of the sea is always cold, but its surface waters have zones very much like those of the land.

For Recitation.—What is an animal? Where do we find the fewest animals? Name some of the animals of the Frigid zone. Where do we find the greatest number of animals that are useful to man? Name same animals that belong to the Temperate zones. What zone contains the greatest number of animals? Name some of the animals that belong to the Torrid zone.

LESSON XV.

MINERALS AND SOIL.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Get the pupils to report what uses they have seen made of stone, and compare stone with brick. Get specimens of metals and building stones.

Get specimens of loam, of sand, and of clay. Let pupils feel the specimens and see how they differ.

Fill two glasses with clear water, and put in one a tablespoonful of coarse sand, and in the other a tablespoonful of fine powdered clay, or of loam. Notice which settles first.

Get a tall glass jar, fill it with water, and pour into it a well-mixed assortment of small pebbles, fine sand, and finely powdered clay. Notice the sorting of materials that takes place while they are settling.

Minerals—We have learned about many plants and animals that are useful to us. Besides these there are also many very useful things that we dig out of the earth. The coal that we burn in our fires, the kerosene oil that gives us light, the granite and sandstone used in building, the salt that we eat at our meals, the diamond that shines like a sunbeam—all come out of the earth.

The rocks, coal, and other things of which the solid earth is composed are called minerals.

Metals.—Some minerals, such as iron, copper and lead, gold and silver, are called metals. The last two, gold and silver, are called the precious metals. They are made into money.

Soils.—But perhaps the most useful part of the earth is the part that we call soil. You have seen soil in the gardens and fields, and you have noticed its color. If you will look closely at a handful of this soil you will see that it is made of fine grains like those of powdered stone. What is called rich soil often contains also particles of decayed leaves or other vegetable or animal material.

For Recitation.—What is a mineral? Name some of the most useful minerals. Name some of the metals. Which are called precious metals? What is soil?

LESSON XVI.

OCCUPATIONS.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Talk to the class about the occupations most familiar to all. Let pupils visit some factory and tell what they saw. A shoe shop, a tailor's shop, a blacksmith shop, are simple factories. Discuss other occupations, and let pupils bring pictures of people at work in any of the loading industries.

Most people earn their living by doing some kind of work. We call people's work their occupation. Let us see what are the great occupations of the world.

We all eat food made from plants, and from plants we get cotton and linen for clothes.

A plowing scene. The dark soil has been plowed.

Now we all know that cabbages and potatoes do not grow of themselves. Just so wheat and corn, the cotton plant, and the flax or linen plant, will not grow of themselves. People must plow the ground for them, plant the seed, reap the grain when it is ripe, cut the flax, and pick the cotton.

Raising corn, or wheat, or other plants for food or clothing is called agriculture or farming.

We do not like to eat dry bread. So some people keep cows and make butter and cheese for the rest. Those who do so are occupied in dairying.

Then, too, we all eat meat. So some people must keep the animals whose flesh we eat. Those animals are called stock, and the business of those who keep them is called stock-raising.

Milking. A dairy in Westchester County, N. Y. Notice the heads of the cows that live upstairs.

Farmers use plows to turn up the soil, and machines to cut their wheat. We all use knives and scissors, needles and pins, and other such things.

People who make the things that other people use are said to manufacture.

But of course the man who makes plows must have iron and wood of which to make them; the man who builds wooden houses must have wood. Where shall they get the iron and the wood?

Iron is a mineral. It is dug from the earth. Some one must dig it up and make it fit for the plow-maker to use. The occupation of digging minerals out of the earth is called mining.

Wood is obtained from oaks and pines and other trees. The occupation of cutting down the trees and sawing them up to be made into houses, or ships, or other things, is called lumbering.

Lumbering. View in Georgia. Railways are used on the coastal plain.

When a boy wants some marbles, he goes to a store and buys them. When a farmer wants a plow, he goes to a store and buys it. If in one country the people have not enough wheat, they buy some from a country where the people have more than enough. If in one country more cotton grows than the people want, they send it to other countries where cotton does not grow. The business of exchanging goods is called commerce.

Often things have to be carried a long way before they reach the persons who want them. The tea or coffee that we use had to travel many thousand miles before it reached us.

This is why we have so many ships and steamers going to all parts of the world. They carry away things that grow or are made here. This we call exporting. They bring to us things that grow or are made in other countries. This we call importing.

Ships from South America unloading at a wharf in New York.

For Recitation.—What are the chief occupations of men? What is agriculture? What is stock-raising? What is in manufacturing? What is mining? What is commerce?

LESSON XVII.

GOVERNMENT AND RELIGION.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Ask the pupils such questions as these: Do you know what an officer is? Did you ever see one? Tell the names of some of the officers you have seen. What does a mayor do? A sheriff? A constable? A justice of the peace? Who makes the laws for your state? Who makes the laws for your town? Answer all questions that pupils cannot answer for themselves.

1. Government.—What a noise there would be in the school if there were no one to keep order! How many wrong things would be done, and how uncomfortable a place it would be!

Teachers, therefore, make rules. They keep the pupils in order, and manage everything for the good of all. They are said to govern the schools.

Towns, cities, and whole countries are somewhat like schools. They must have rules and rulers, or else a few disorderly people might make it unpleasant for all the rest. Making rules for a country, and making the people obey the rules, is government.

The rules made for a country are called its laws. The city where the laws are made is its capital.

The rulers of different countries have different names. A ruler that is chosen by the people is usually called a president. One that rules because a father or other near relative ruled previously, is a monarch.

Monarchs are sometimes called kings, or queens, or emperors.

If the ruler of a country makes laws which are selfish, oppressive to the people, and opposed to their advancement, he is called a despot.

Countries that have presidents are called republics; those that have kings are called kingdoms; those that have emperors are called empires. Kingdoms and empires are sometimes called monarchies.

Republics, and other countries, are often composed of parts, which are called by various names. With us they are known as states and territories.

The governor of a state is elected by the people. The governor of a territory is appointed by the president.

2. Religion.—The belief in God, together with the various forms of worshiping Him, is called religion.

Christians believe in one God and that Christ is the Savior of the world. They accept the Old and New Testaments as the Word of God.

The Jews also believe in one God, but maintain the Savior has not yet come.

Mohammedans believe in one God, but recognize Mohammed as His greatest prophet. Many Mohammedans are but half civilized.

There are people in the world who do not believe in one God, but think that there are many gods. Such people are called pagans. Some of them worship images of wood or stone, which we call idols.

The place where people worship is called a church, a synagogue, a mosque, or a temple.

St. Peter's church at Rome, the largest in the world.

For Recitation.—What is government? What is a republic? What is a kingdom? What is an empire? What are the chief religions of the world? Who are pagans?

LESSON XVIII.

RACES OF MEN—CIVILIZATION.

seen a Caucasian, an Indian, a Malay, a Mongolian. Show how the people of any race may be savage or barbarous; how the people of any race may be civilized or enlightened. Impress the fact that these conditions are due to the manner of living and not to the race.

1. How Men Look.—The people who live on the earth do not all look alike. They differ in the color of their skins and in other ways.

Most of those that we see are white; some are black. In the western part of our country there are a good many red men, and in some parts yellow men, or Chinese, are found. In other parts of the world we find men of one more color still, the brown.

These five are the races of men.

The white is called the Caucasian race; the yellow, the Mongolian race; the black, the Negro race; the red, the Indian race; the brown, the Malay race.

White men now live in every continent, and control the world.

The people of the Caucasian or white race are not always of fair complexion; those that live in a hot, sunny country are often dark. Thus many of the Arabs have swarthy skins, black eyes, and black glossy hair. The other races also vary a little in color, according to the climate in which they live.

| ||

| A Mongolian. | An Indian chief. | A Malay in European dress. |

| Although these three differ in color they are much alike. Notice their high cheek bones, almond shaped eyes, and straight black hair. | ||

2. How Men Live.—The different people of the earth do not all live in the same way.

Suppose we go to the homes of the wild Indians or Negroes and see how they live. We shall find some of them living in tents made of skins or in rude huts.

Among the wild tribes the people wear little or no clothing, and eat roots, insects, fish, or the wild animals they may be able to trap or kill with clubs, wooden spears, or bows and arrows, for they have not yet learned the use of iron. The women do most of the work, while the men hunt and are fond of fighting.

People who live in this way are called savages.

After living for a long time like savages some people learned to make pottery from clay, to cultivate grain, and to tame and keep herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. They also learned to weave coarse cloth, and to make tools and weapons of metal. They cannot read or write, but they live more comfortably than savages, and are known as barbarous people.

Savage life. Photograph by Dr. Cook in South America.

Some of these people live in tents, and wander about from place to place with their herds, pitching their tents wherever there is grass for their animals. Many of the wandering desert tribes live in this manner.

We will now visit some people who live very much better than barbarous people. They are the Chinese, who are going to bed as we are getting up.

Barbarous life. Arabs eating dinner before the tent which is their only home.

Instead of tents they have comfortable houses. They build large cities, and make beautiful silks and many other things. They have books and schools, are industrious, and are adopting many modern customs and inventions. We call people who live like the Chinese partly or half civilized.

Half civilized life. A Chinese city. Compare this with one of our cities.

In the countries of the white race there are more books, and better schools and governments than anywhere else. We have churches, railways, steamers, telegraphs, and telephones. We build hospitals, and care for the poor. People living as we do are called fully civilized or enlightened.

Among enlightened people. Notice the large courthouse and the very tall buildings. The city is St. Louis, Mo.

For Recitation.—Name the five races of men. How do savages live? How do barbarous people live? How do civilized people live? How do enlightened people live?

LESSON XIX.

THE HEMISPHERES.

Preparatory Oral Work.—Let each pupil make a clay sphere and scratch on it some shapes to represent land. Color the rest of the sphere with blue ink or paint to represent water. Divide each sphere into halves. Teach meaning of terms sphere and hemisphere.

Sometimes the earth is called a sphere. The word sphere is only another name that is often used for a body shaped like a ball. When a sphere is divided into two equal parts, each half is called a hemisphere, that is a half sphere.

On the following pages we have maps of the two halves of the earth. One half is called the western hemisphere, and the other half is known as the eastern hemisphere. Each hemisphere represents half of the earth's surface, with its continents, oceans, and some of its largest islands, mountains, rivers, and other objects.

Europe and Asia, and the oceans around them, as they would look if seen from the moon.

If we look at the maps of the hemispheres on pages 28 and 29, we shall see that there is much more land in the eastern hemisphere than in the western. Four of the six continents are in the eastern hemisphere. These are Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. The western hemisphere contains only two continents. They are North America and South America.

The blue which we see on the map represents the water. The water has five great divisions or oceans. They are the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Indian, the Arctic, and the Antarctic oceans.

All these oceans except the Indian are partly in the eastern hemisphere and partly in the western. But the western hemisphere has a much larger share of water than the eastern.

Nearly one-half of all the land surface of the earth is in the North Temperate zone, and more than one-half of all the people in the world live in it.

For Recitation.—What is a hemisphere? Name the hemispheres shown on the map. What continents are in the western hemisphere? What continents are in the eastern hemisphere? Name the oceans. In which hemisphere is the Indian ocean? Where are the other oceans?

LESSON XX.

CONTINENTS AND OCEANS.

1. Having learned the names of the continents and oceans, let us now notice some of the most interesting things about them.

2. Europe.— Let us cross the Atlantic and take a flying trip through Europe. Next to Australia it is the smallest of the continents. It lies chiefly in our own North Temperate zone. Most of the people are Caucasians. As we travel among them we hear a great many different languages that we do not understand.

Their cities contain many interesting and beautiful churches, palaces, and museums full of pictures and all sorts of curious things.

Schools and churches are to be seen everywhere, except in one part, called Turkey; railways extend, in every direction, and steamboats run on all the great rivers. We find the people busy on farms, in workshops, and in factories.

From Europe we buy more things than from any other continent, and to it we sell more than to any other.

3. Asia.—Leaving Europe, we pass into Asia. To-day we can make this trip by railroad trains. Asia is the largest continent. It is chiefly in the North Temperate zone. The people on its eastern coast are just half-way round the earth from us. In Asia we find the highest mountains in the world.

More people live on this continent than in all the others together. But there are not so many schools as in Europe and America, and the people are not so enlightened.

Africa, and the oceans around it.

They belong chiefly to the yellow, the white, and the brown races. Some wear turbans instead of hats; others wear their hair in braids or queues (kews) two or three feet long.

4. Africa.—Suppose we now journey from Asia toward the west, and across the Isthmus of Suez, where shall we be? In Africa—the second continent in size, and the hottest of all. Most of it lies in the Torrid zone, and it contains the largest desert in the world.

Africa is the home of the Negro race. Many of the Negro tribes are ignorant savages. People from Europe have settled along the coast and in parts of the interior, and have introduced railways and schools.

5. Australia.—From Africa let us take a steamship and go east across the Indian ocean. We come to Australia, the smallest of the continents. It is partly in the South Temperate zone and partly in the Torrid.

When it was discovered only black savages lived there, but now most of its people are English. The plants and animals of Australia are unlike those of any other continent. The leaves of some of the trees are turned edgewise. Many trees shed their bark instead of their leaves. Australia produces a great amount of wool, wheat, and gold.

South America, and the oceans around it.

6. South America.—Sailing now across the Pacific ocean, we come to the western continents. Let us first visit South America, It lies chiefly in the Torrid zone, and is very hot and very moist. Here we find one of the largest rivers and the longest mountain range in the world.

South America is the nearest continent to us, but its people are very different from us. They speak languages unlike ours, and are not nearly so busy as we are. No continent has more beautiful flowers, birds, and insects.

North America, and the oceans around it.

7. North America.—Having visited the other continents, we return to North America, and find that, after all, there is no place like home. Our continent is mainly in the North Temperate zone. Its lands are fertile; it produces nearly everything that we need for food or clothing.

It was once the hunting ground of the red man, but more than four hundred years ago the white man came from Europe and took it for himself. The red man now owns little of the land that belonged to his fathers.

8. Atlantic Ocean.—On the Atlantic there are more ships than on any other ocean, because Europe and North America, which lie on either side of it, carry on more trade than the other continents. Ships, carrying passengers and goods, are constantly crossing this ocean.

In the Atlantic there is a great stream of warm water that comes out of the Gulf of Mexico. It is the Gulf stream. It flows northeastward, and, broadening out, joins the other Atlantic waters and drifts over to the shores of Europe.

9. The Pacific Ocean was found calm and peaceful by the first European that sailed on it, and this is the reason why he called it Pacific or peaceful. It is the largest of all the oceans, and contains more islands than any other.

There is in the Pacific ocean a current of water similar to the Gulf stream. It is called the Japan current.

10. The Indian Ocean is sometimes visited by violent tempests called typhoons; and if we sail upon it we may be terrified by a waterspout.

Waterspouts are huge columns of water and vapour extending from the sea towards the clouds. They are formed by a whirlwind, larger but much like the small whirlwinds that we see forming columns of dust in the street and roads.

11. The Arctic and Antarctic Oceans' are seldom visited by ships. Icebergs or mountains of ice float in them.

On page 94 we may learn something about the great streams of ice called glaciers. In the Arctic and Antarctic, regions the glaciers flow down into the ocean. Great fragments are broken off and are carried away by the ocean currents. These are icebergs, or ice mountains.

For Recitation.—Can you tell anything Interesting about Europe? What can you tell about Asia? What can you say about Africa? What can you say of Australia? What have you learned about South America? Tell me something about North America. What have you learned about the different oceans?

WESTERN HEMISPHERE

MAP STUDIES.

What part of the map is north? South? East? West? What two continents are in the western hemisphere? In what direction is North America from South America? Point in the direction in which South America lies from us.

By what isthmus are North and South America connected? What ocean on the east of them? On the west?

What ocean round the North pole? What ocean round the South pole?

What four continents in the eastern hemisphere? What isthmus between Asia and Africa? In what direction is Africa from Asia?

Point in the direction in which Africa lies from us. In what direction is Australia from Asia?

What sea separates Africa and Europe? In what direction is Europe from Africa? Point in the direction in which Europe lies from us.

What ocean east of Asia? What ocean west of Africa? What ocean north of Europe and Asia?

What ocean between Africa and Australia?

What is the heavy black line crossing the middle of the hemispheres from east to west called? Equator means dividing equally.

EASTERN HEMISPHERE

What continents lie wholly north of the equator?

What continent lies wholly south of it? Which two are crossed by the equator? Is there more land north or south of the equator?

Which hemisphere contains the larger amount of land? What ocean must be crossed to go from South America to Africa? From North America to Europe?

In what direction is Europe from Asia? Africa from South America? Point in the direction in which Asia lies from us.

In what direction is the north pole from the south pole? The north pole from the equator? The south pole from the equator?

What continents form the Old World? Which form the New World? Point out an island, peninsula, cape.

What oceans would you cross in sailing from Australia westward to South America? What islands lie between North America and South America? What islands lie between Asia and Australia? What large island east of Africa? Name some islands found in the Pacific ocean. In the Atlantic ocean. In the Indian ocean.

Name some of the large rivers that you see on each of the continents. Name the ocean into which each flows.

What continents are crossed by the Tropic of Cancer? What continents are crossed by the Tropic of Capricorn?