Narrative Of The United States Expedition To The River Jordan And The Dead Sea/14

CHAPTER XIV.

EXPEDITION AROUND THE SOUTHERN SEA

TUESDAY, APRIL 25. Completed a set of observations, bundled up the mess things, and started, at 9:40, for a reconnoissance of the southern part of the sea; leaving Sherîf in charge of the camp, with Read and the four Turkish soldiers. Steered about south, from point to point, keeping near the Arabs along the shore, for their protection; for they dreaded an attack from marauding parties. Threw the patent log overboard; the weather fair but exceedingly hot; thermometer, 89°; little air stirring; no clouds visible; the mountains, as we passed, seemed terraced, but the culture was that of desolation.

At 11:05, the patent log had marked 21 knots; depth, six feet; bottom, of brown mud; made for a current ripple, a little farther out, coloured with decomposed wood, membranes of leaves, chaff, &c.; depth, thirteen fathoms; hard bottom; resumed the course along the shore. At 12:30, abreast of a ravine, or wady, not down on the maps, with a broad, flat delta before it. These ravines all have names, among the Arabs; but the deltas, or projecting plains, are undesignated. The limestone strata of the mountain above it were horizontal. There was a line of verdure up the ravine, indicating the presence of water. The log had measured 6¼ nautical miles from Ain Jidy soundings, a musket-shot distance from the shore, one fathom; bottom, white sand and very fine gravel. At 12:40, soundings one fathom; north end of the pensula bearing east; steered towards it, to try for ford; water deepening to 2½ fathoms (fifteen feet), pulled into the shore-line again.

ANCIENT FORTIFICATION

A small, beautiful bird, with yellow breast, flew along the shore. Occasionally sounded out to 2½ fathoms, one mile from shore, to look for ford. At 1:58, abreast of Wady Sêyâl Sebbeh (ravine of Acacias), supposed to have water in it, very high up, the log having marked 8½ nautical miles. The cliff above the ravine was that of Sebbeh, or Masada. It was a perpendicular cliff, 1200 to 1500 feet high, with a deep ravine breaking down on each side, so as to leave it isolated. On the level summit was a line of broken walls, pierced in one place with an arch. This fortalice, constructed by Herod, and successfully beleaguered by Silva, had a commanding but dreary prospect, overlooking the deep chasm of this mysterious sea. Our Arabs could give no other account of it than that there were ruins of large buildings on the cliff.

The cliff of Sebbeh is removed some distance from the margin of the sea by an intervening delta of sand and detritus, of more than two miles in width. A mass of scorched and calcined rock, regularly laminated at its summit, and isolated from the rugged strip, which skirts the western shore, by deep and darkly-shadowed defiles and lateral ravines, its aspect from the sea is one of stern and solemn grandeur, and seems in harmony with the fearful records of the past.

There was that peculiar purple hue of its weather-worn rock, a tint so like that of coagulated blood that it forced the mind back upon its early history, and summoned images of the fearful immolation of Eleazar and the nine hundred and sixty-seven Sicarii, the blood of whose self-slaughter seemed to have tinged the indestructible cliff forever.

GEOLOGY OF THE WESTERN SHORE

At 3:05 P.M. a fine northerly wind blowing; stopped to take in our Arabs. They brought a piece of bitumen, found on the shore, near Sebbeh, where we had intended to camp; but the wind was fair, and there was an uncertainty about water. We ascertained that there is no ford as laid down in the map of Messrs. Robinson and Smith. One of the Arabs said that there was once a ford there, but all the others denied it. Passed two ravines and the bluff of Rubtat el Jamus (Tying of the Buffalo), and at 4:45, stopped for the night in a little cove, immediately north of Wady Mubughghik, five or six miles north of the salt-mountain of Usdum, which looms up, isolated, to the south. From Ain Jidy to this place, the patent log has measured 13 nautical miles, which is less than the actual distance, the log sometimes not working, from the shoalness of the water.

We this day paid particular attention to the geological construction of the western shore, with a special regard to the disposition of the ancient terraces and abutments of the tertiary limestone and marls. There may be rich ores in these barren rocks. Nature is ever provident in her liberality, and when she denies fertility of surface, often repays man with her embowelled treasures. There is scarce a variety of rock that has not been found to contain metals; and it is said that the richness of the veins is for the most part independent of the nature of the beds they intersect.

There has been no great variety in the scenery, to-day; the same bold and savage cliffs; the same broad peninsulas, or deltas, at the mouths of the ravines, some of them sprinkled here and there with vegetation, — all evincing the recent or immediate presence of water. This part of the coast is claimed by no particular tribe; but is common to roaming bands of marauders.

RAVINE, WITH RUINS

The beach was bordered with innumerable dead locusts. There was also bitumen in occasional lumps, and incrustations of lime and salt. The bitumen presented a bright, smooth surface when fractured, and looked like a consolidated fluid. The Arabs called it hajar Mousa (Moses’ stone).

Our Arabs insisted upon it that the only ford was at the southern extremity of the sea. There were seven of them with us, and they were of three tribes, the Rashayideh, Ta’amirah and Kabeneh. Being beyond the limits of their own territories, they were very apprehensive of an attack from hostile tribes.

When, this afternoon, under the impression, which proved to be correct, that there was water in the ravine, we called to them, they came down in all haste, unslinging their guns as they ran, in the supposition that we were attacked, — evincing, thereby, more spirit than we had anticipated. They were very uneasy; and, immediately after our arrival, one of them was perched, like a goat, upon a high cliff; and the others had bivouacked where they commanded a full view into the mouth of the ravine.

Our camp was in a little cove, on the north side of the delta, which had been formed by the deposition of the winter torrents, and extends half a mile out, with a rounding point to the eastward. The ravine comes down between two high, round-topped mountains, of a dark, burnt-brown colour, and a horizontal, terrace-like stratum, halfway up. In the plain were several nubk and tamarisk trees, and three kinds of shrubs, and some flowers which we gathered for preservation. Near the ravine, on a slight eminence, we discovered the ruins of a building, with square-cut stones, — the foundation-walls alone remaining, and a line of low wall running down to the ravine; near it was a rude canal. There were many remains of terraces. The low wall was, perhaps, an aqueduct for the irrigation of the plain.

About half a mile up, the faces of the ravine cut down through limestone rock, and turned, at right angles, a short distance above, with here and there a few bushes in the bottom. We found a little brook purling down the ravine, and soon losing itself in the dry plain. We were now almost at the southern extremity of the sea. The boats having been drawn up on the beach, their awnings were made to supply the places of tents, the open side facing the ravine; the blunderbuss at our head, and the sentries walking beside it. At 8 P.M., there were a few light cumuli in the sky, but no wind. At 8:30, a hot fresh wind from north-west; thermometer, 82°; at 9, 86°. Finding it too oppressive under the awning, we crawled out upon the open beach, and, with our feet nearly at the water’s edge, slept “à la belle etoile.” After the manner of the poor highwayman, we slept in our clothes, under arms, and upon the ground. It continued very hot during the night, and we could not endure even a kerchief over our faces, to screen them from the hot and blistering wind. This was doubtless a sirocco, but it came from an unusual quarter. At midnight, the thermometer stood at 88°; and at 4, the temperature of the air, 86°; of the water, 80°. Towards daylight, the wind went down, and the thermometer fell to 79°. There were several light meteors, from the zenith towards the north, seen during the night. While the wind lasted, the atmosphere was hazy. Notwithstanding the oppressive heat, there was a pleasure in our strange sensations, lying in the open air, upon the pebbly beach of this desolate and unknown sea, perhaps near the sites of Sodom and Gomorrah; the salt mountains of Usdum in close proximity, and nothing but bright, familiar stars above us.

LANDING AT USDUM

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 26. When I awoke this morning there was a young quail at my side, where, in the night, it had most probably crept for shelter from the strong, hot wind.

We were up before sunrise; light variable airs and warm weather. At 5:30, started and steered S.½ E. in a direct line for Ras Hish (cape Thicket), the north point of Usdum. At 6:42, fifty yards from the shore, sounded, the depth one fathom. Wady Mubughghik bearing west. 6:51, soundings one and three-quarter fathoms, grey mud. At 7, two fathoms, black, slimy mud. A light wind sprang up from S.S.E., a few light cirrus clouds in the N.E. The cliffs gradually slope away and terminate in Usdum. Sounding every few minutes for the ford; stretching out occasionally from the shore line, and returning to it again, when the water deepened to two fathoms. The Fanny Skinner coasted along the shore to sketch the topography, and we kept further out to sound for the ford. At 8 , abreast of a short, steep, shrubby ravine, Muhariwat (the Surrounded); a very extensive excavation at its mouth. In front of the ravine was a beautiful patch of vegetation, extending towards Usdum, with intervals of gravel and sand. Many of these ravines derive their names from incidents in Arab history.

At 8:07, stopped to take bearings. Wady Ez Zuweirah, S.W. by W.; the west end of Usdum, S. by W.; marshy spit, north end of do., S.E. ½ E. Usdum is perfectly isolated, but has no appearance of being a mass of salt. Perhaps, like the peninsula, it is incrusted with carbonate of lime, which gives it the tinge of the eastern and western mountains.

At 8:08, water shoaling to two and a half feet, hauled off; 8:12, stood in and landed on the extreme point of Usdum. Many dead bushes along the shore, which are incrusted with salt as at the peninsula. Found it a broad, flat, marshy delta, the soil coated with salt and bitumen, and yielding to the foot.

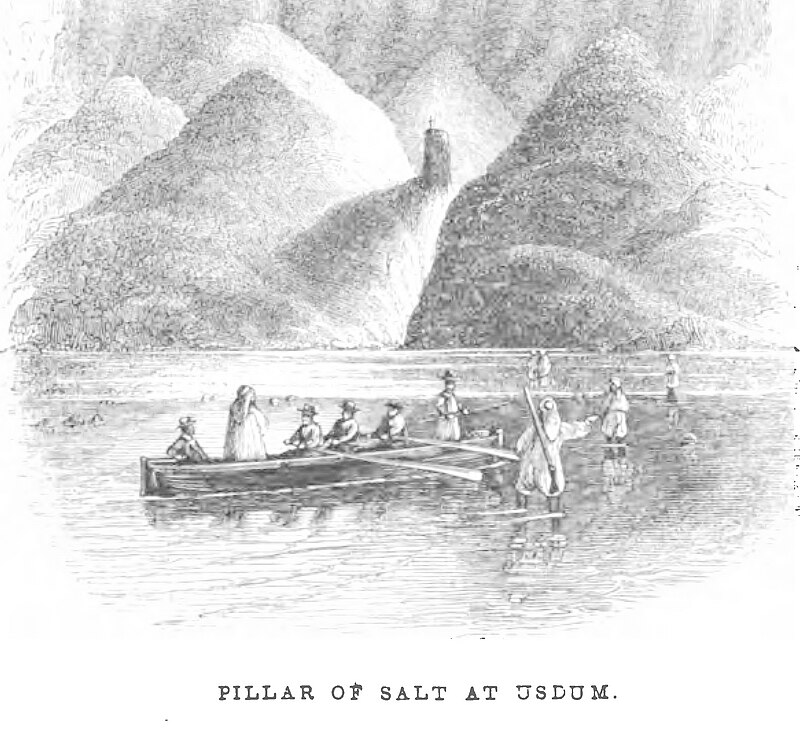

PILLAR OF SALT

At 8:30, started again and steered E.S.E., sounding every five minutes, the depth from one to one and three-quarter fathoms; white and black slime and mud. A swallow flew by us. At 8:52, stopped to take compass bearings. Seetzen saw this salt mountain in 1806, and says that he never before beheld one so torn and riven; but neither Costigan nor Molyneaux, who were in boats, came farther south on the sea than the peninsula. With regard to this part, therefore, which most probably covers the guilty cities, —

“We are the first

That ever burst

At 9, the water shoaling, hauled more off shore. Soon after, to our astonishment, we saw on the eastern side of Usdum, one third the distance from its north extreme, a lofty, round pillar, standing apparently detached from the general mass, at the head of a deep, narrow, and abrupt chasm. We immediately pulled in for the shore, and Dr. Anderson and I went up and examined it.

The beach was a soft, slimy mud encrusted with salt, and a short distance from the water, covered with saline fragments and flakes of bitumen. We found the pillar to be of solid salt, capped with carbonate of lime, cylindrical in front and pyramidal behind. The upper or rounded part is about forty feet high, resting on a kind of oval pedestal, from forty to sixty feet above the level of the sea. It slightly decreases in size upwards, crumbles at the top, and is one entire mass of crystallization. A prop, or buttress, connects it with the mountain behind, and the whole is covered with debris of a light stone colour. Its peculiar shape is doubtless attributable to the action of the winter rains. The Arabs had told us in vague terms that there was to be found a pillar somewhere upon the shores of the sea; but their statements in all other respects had proved so unsatisfactory, that we could place no reliance upon them.*

.* A similar pillar is mentioned by Josephus, who expresses the belief of its being the identical one into which Lot’s wife was transformed. His words are, “But Lot’s wife continually turning back to view the city as she went from it, and being too nicely inquisitive what would become of it, although God had forbidden her so to do, was changed into a pillar of salt, for I have seen it, and it remains at this day?” — 1 Josephus’ Antiq., book 1, chap. 12.

A BITTER MELON

At 10:10, returned to the boat with large specimens. The shore was soft and very yielding for a great distance; the boats could not get within 200 yards of the beach, and our foot-prints made on landing, were, when we returned, incrusted with salt.

Some of the Arabs, when they came up, brought a species of melon they had gathered near the north spit of Usdum. It was oblong, ribbed, of a dark green colour, much resembling a cantelope. When cut, the meat and seeds bore the same resemblance to that fruit, but were excessively bitter to the taste. A mouthful of quinine could not have been more distasteful, or adhered longer and more tenaciously to the reluctant palate.

Intending to examine the south end of the sea, and then proceed over to the eastern shore in the hope of finding water, we discharged all our Arabs but one, and sharing our small store of water with them, and giving them provisions, we started again at 10:30, and steered south.

At 10:42, a large black and white bird flew up, and lighted again upon the shore. The salt on the face of Clement of Rome, a contemporary of Josephus, also mentions this pillar, and likewise Irenaeus, a writer of the second century, who, yet more superstitious than the other two, adds the hypothesis, how it came to last so long with all its members entire. Reland relates an old tradition that as fast as any part of this pillar was washed away, it was supernaturally renewed.

A MUDDY SHORE

Usdum appeared in the form of spiculae. At 11:07, came to the cave in Usdum described by Dr. Robinson; kept on, to take meridian observation at the extreme south end of the sea. 11:28, unable to proceed any further south from shallowness of the water, having run into six inches, and the boats’ keels stirring up the mud. The Fanny Skinner having less draught, was able to get a little nearer to the shore, but grounded 300 yards off. Lieut. Dale landed to observe for the latitude. His feet sank first through a layer of slimy mud a foot deep, then through a crust of salt, and then another foot of mud, before reaching a firm bottom. The beach was so hot as to blister the feet.

From the water’s edge, he made his way with difficulty for more than a hundred yards over black mud, coated with salt and bitumen. Unfortunately, from the great depth of this chasm, and the approach of the sun towards the tropic of Cancer, the sextant (one of Gambey’s best) would not measure the altitude with an artificial horizon, and there was not sufficient natural horizon for the measurement. We therefore took magnetic bearings in every direction, which, with observations of Polaris, would be equally correct, but more laborious. We particularly noted the geographical position of the south end of Usdum, which was now a little south of the southern end of the sea. The latter is ever-varying, extending south from the increased flow of the Jordan and the efflux of the torrents in winter, and receding with the rapid evaporation, consequent upon the heat of summer.

In returning to the boat, one of the men attempted to carry Lieut. Dale to the water, but sunk down, and they were obliged separately to flounder through. When they could, they ran for it. They describe it as like running over burning ashes, — the perspiration starting from every pore with the heat.

A MUDDY BOTTOM

It was a delightful sensation when their feet touched the water, even the salt, slimy water of the sea, then at the temperature of 88°. The southern shore presented a mud-flat, which is terminated by the high hills bounding the Ghor to the southward. A very extensive plain or delta, low and marshy towards the sea, but rising gently, and, farther back, covered with luxuriant green, is the outlet of Wady es Safieh (clear ravine), bearing S.E. by S. Anxious to examine it, we coasted along, just keeping the boat afloat, the in-shore oars stirring up the mud. The shore was full three-fourths of a mile distant, the line of demarcation scarce perceptible, from the stillness of the water, and the smooth, shining surface of the marsh. On the flat beyond, were lines of drift-wood, and here and there, in the shallow water, branches of dead trees, which, like those at the peninsula, were coated with saline encrustation. The bottom was so very soft, that it yielded to everything, and at each cast the sounding-lead sank deep into the mud. Thermometer, 95°. Threw the drag over, but it brought up nothing but soft, marshy, light coloured mud.

It was indeed a scene of unmitigated desolation. On one side, rugged and worn, was the salt mountain of Usdum, with its conspicuous pillar, which reminded us at least of the catastrophe of the plain; on the other were the lofty and barren cliffs of Moab, in one of the caves of which the fugitive Lot found shelter. To the south was an extensive flat intersected by sluggish drains, with the high hills of Edom semi-girdling the salt plain where the Israelites repeatedly overthrew their enemies; and to the north was the calm and motionless sea, curtained with a purple mist, while many fathoms deep in the slimy mud beneath it lay embedded the ruins of the ill-fated cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. The glare of light was blinding to the eye, and the atmosphere difficult of respiration.

LOFTY HILLS

No bird fanned with its wing the attenuated air through which the sun poured his scorching rays upon the mysterious element on which we floated, and which, alone, of all the works of its Maker, contains no living thing within it.

While in full view of the peninsula, I named its northern extremity “Point Costigan,” and its southern one “Point Molyneaux,” as a tribute to the memories of the two gallant Englishmen who lost their lives in attempting to explore this sea.

At 11:42, much frothy scum; picked up a dead bird resembling a quail; sounding every five minutes, depth increasing to four feet, bottom a little firmer; the only ford must be about here.

At 12:21, there was a very loud, reverberating report, as of startling thunder, and a cloud of smoke amid dust on the western shore; most probably a huge rock falling from a high cliff.

At 2:35 P.M., close in with the eastern shore, but unable to land from the soft bottom and shoalness of the water. At 2:50, a light breeze from W.N.W.; hauled to the north towards the base of the peninsula. A long, narrow, dry marsh, with a few scrubby bushes, separated the water from a range of stupendous hills, 2000 feet high. The cliff of En Nuweireh (Little Tiger), lofty and grand, towered above us in horizontal strata of brown limestone, and beautiful rose-coloured sandstone beneath. Clouds in the east, nimbus, seemed to be threatening a gust. At 3:30, steered N.N.E. along a low marshy flat, in shallow water. The light wind had subsided, and it was oppressively hot; air 97°; water twelve inches below the surface 90°. A thin purple haze over the mountains, increasing every moment, and presenting a most singular and awful appearance; the haze so thin that it was transparent, and rather a blush than a distinct colour.

ANOTHER SIROCCO

I apprehended a thunder-gust or an earthquake, and took in the sail. At 3:50, a hot, blistering hurricane struck us from the south-east, and for some moments we feared being driven out to sea. The thermometer rose immediately to 102°. The men, closing their eyes to shield them from the fiery blast, were obliged to pull with all their might to stem the rising waves, and at 4:30, physically exhausted, but with grateful hearts, we gained the shore. My own eye-lids were blistered by the hot wind, being unable to protect them, from the necessity of steering the boat.

We landed on the south side of the peninsula, near Wady Humeir, the most desolate spot upon which we had yet encamped. Some went up the ravine to escape from the stifling wind; others, driven back by the glare, returned to the boats and crouched under the awnings. One mounted spectacles to protect his eyes, but the metal became so heated that he was obliged to remove them. Our arms and the buttons on our coats became almost burning to the touch; and the inner folds of our garments were cooler than those exposed to the immediate contact of the wind. We bivouacked without tents, on a dry marsh, a few dead bushes around us, and some of the thorny nubk, and a tree bearing a red berry a short distance inland, with low canes on the margin of the sea. A short distance to the N.E., on the peninsula, we found fragments of an immense and very old mill-stone. The mill had, doubtless, been turned by a canal from the ravine, down which the water must flow copiously in the rainy season.

EFFECTS OF THE HOT WIND

At 5, finding the heat intolerable, we walked up the dry torrent bed in search of water. Found two successive pools rather than a stream, with some minnows in them; the water, not yet stagnant, flowing from the upper to the lower pool. There were some succulent plants on their margins, and fern roots, and a few bushes around them. There were huge boulders of sandstone in the bed of the ravine; a dead palm-tree near the largest pool, a living one in a cleft of the rock at the head of the gorge; and high up, to the summits of the beetling cliffs, the sandstone lay in horizontal strata, with perpendicular cleavage, and limestone above, its light brown colour richly contrasting with the deep red below.

The sandstone below limestone here, and limestone without sandstone on the opposite shore, would seem to indicate a geological fault.

Washed and bathed in one of the pools, but the relief was only momentary. In one instant after leaving the water, the moisture on the surface evaporated, and left the skin dry, parched, and stiff. Except the minnows in the pool, there was not a living thing stirring; but the hot wind swept moaning through the branches of the withered date palm-tree, and every bird and insect, if any there were, had sought shelter under the rocks.

Coming out from the ravine, the sight was a singular one. The wind had increased to a tempest; the two extremities and the western shore of the sea were curtained by a mist, on this side of a purple hue, on the other a yellow tinge; and the red and rayless sun, in the bronzed clouds, had the appearance it presents when looked upon through smoked glass. Thus may the heavens have appeared just before the Almighty in his wrath rained down fire upon the cities of the plain. Behind were the rugged crags of the mountains of Moab, the land of incest, enveloped in a cloud of dust, swept by the simoom from the great desert of Arabia.

WELL-FORMED ARABS

There was a smoke on the peninsula, a little to the north of us. We knew not whether those who made it might prove friends or foes; and therefore that little smoke was not to be disregarded. We had brought one of the Ta’amirah with us, for the express purpose of communicating with the natives, but he was so fearful of their hostility that I could not prevail on him to bear a message to them. With his back to the wind, and his eyes fixed on the streaming smoke, he had squatted himself down a short distance from us. He thought that we would be attacked in the night; I felt sure that we would not, if we were vigilant. These people never attack each other but at advantage, and fifteen well-armed Franks can, in that region, bid defiance to anything but surprise. We have not seen an instance of deformity among the Arab tribes. This man was magnificently formed, and when he walked it was with the port and presence of a king. It has been remarked that races with highly coloured skins are rarely deformed; and the exemption is attributed, perhaps erroneously, not to a mode of life differing from that of a civilized one, but to hereditary organization.

The sky grew more angry as the day declined;

“The setting orb in crimson seems to mourn,

Denouncing greater woes at his return,

And adds new horrors to the present doom

The heat rather increased than lessened after the sun went down. At 8 P.M., the thermometer was 106° five feet from the ground. At one foot from the latter it was 104°. We threw ourselves upon the parched, cracked earth, among dry stalks and canes, which would before have seemed insupportable from the heat. Some endeavoured to make a screen of one of the boats’ awnings, but the fierce wind swept it over in an instant. It was more like the blast of a furnace than living air. At our feet was the sea, and on our right, through the thicket, we could distinguish the gleaming of the fires and hear the shouts from an Arab encampment.

HEAT AND THIRST

In the early part of the night, there was scarce a moment that some one was not at the water-breakers; but the parching thirst could not be allayed, for, although there was no perceptible perspiration, the fluid was carried off as fast as it was received into the system. At 9, the breakers were exhausted, and our last waking thought was water. In our disturbed and feverish slumbers, we fancied the cool beverage purling down our parched and burning throats. The mosquitoes, as if their stings were envenomed by the heat, tormented us almost to madness, and we spent a miserable night, throughout which we were compelled to lie encumbered with our arms, while, by turns, we kept vigilant watch.

We had spent the day in the glare of a Syrian sun, by the salt mountain of Usdum, in the hot blast of the sirocco, and were now bivouacked under the calcined cliffs of Moab. When the water was exhausted, all too weary to go for more, even if there were no danger of a surprise, we threw ourselves upon the ground, — eyes smarting, skin burning, lips, and tongue, and throat parched and dry; and wrapped the first garment we could find around our heads to keep off the stifling blast; and, in our brief and broken slumbers, drank from ideal fountains.

Those who have never felt thirst, never suffered in a Simoom in the wilderness, or been far off at sea, can form no idea of our sensations. They are best illustrated by the exclamation of the victim in Dante’s Inferno.

“The little rills which down the grassy side

Of Casentino flow to Arno’s stream,

Filling their banks with verdure as they glide,

Are ever in my view; — no idle dream —

For more that vision parches, makes me weak,

Than that disease, which wastes my pallid cheek?”

THE HEAT ABATES

Our thoughts could not revert to home save in connexion with the precious element; and many were the imaginary speeches we made to visionary common councils against ideal water-carts, which went about unsubstantial city streets, spouting the glorious liquid in the very wastefulness of abundance, every drop of which seemed priceless pearls, as we lay on the shore of the Dead Sea, in the feverish sleep of thirst.

The poor, frighted Arab slept not a wink; — for, repeatedly, when I went out, as was my custom, to see that all was quiet and the sentries on the alert, he was ever in the same place, looking in the same direction.

At midnight the thermometer stood at 98°; shortly after which the wind shifted and blew lightly from the north. At 4 A.M., thermometer, 82°; comparatively cool.

THURSDAY, APRIL 27: The first thing on waking, at daybreak, I saw a large, black bird, high overhead, floating between us and the mottled sky. Shortly after, a large flock of birds flew along the shore, and a number of storks were noiselessly winging their way in the gray and indistinct light of the early morning. Calm and warm; — went up and bathed in the ravine. There were voices in the cliffs overhead, and shortly after there was the report of a gun, the reverberating echoes of which were distinctly heard at the camp. As I had come unattended, the officers were alarmed, and some came to look for me. Our Arab was exceedingly nervous. The gun was doubtless a signal from a look-out on the cliff to his friends inland, for these people live in a constant state of civil warfare, and station sentinels on elevated points to give notice of a hostile approach. I thought that we inspired them with more fear than they did us. Heard a partridge up in the cliffs, and saw a dove and a beautiful humming-bird in the ravine.

A MENACED ATTACK

There were some fellahas (female fellahin) on a plain to the northward of us. They allowed Mustafa to approach within speaking distance, but no nearer. They asked who we were, how and why we came, and why we did not go away. About an hour after, some thirty or forty fellahin, the sheikh armed with a sword, the rest with indifferent guns, lances, clubs, and branches of trees, came towards us, singing the song of their tribe. I drew our party up, the blunderbuss in front, and, with the interpreter, advanced to meet them. When they came near, I drew a line upon the ground, and told them that if they passed it they would be fired upon. Thereupon, they squatted down, to hold a palaver. They belonged to the Ghaurariyeh, and were as ragged, filthy, and physically weak, as the tribe of Rashayideh, on the western shore. Finding us too strong for a demand, they began to beg for backshish. We gave them some food to eat, for they looked famished; also a little tobacco and a small gratuity, to bear a letter to ’Akil , (who must soon be in Kerak,) appointing when and where to have a look-out for us.

Before starting, we took observations, and angled in every direction. Not far from us must be the site of Zoar; and on some of these mountains Lot dwelt with his two daughters. This country is called Moab, after the son of the eldest daughter. Moab means one begotten by a father.

At 8:45, started; sky cloudless, a light air from the west; thermometer, 94°. The Arabs gathered on the shore to see us depart, earnestly asking Mustafa how the boats could move without legs; he bade them wait awhile, and they would see very long legs. The Fanny Mason sounded directly across to the western shore; the casts, taken at short intervals, varying from one and three-quarters to two and a quarter fathoms; bottom, light and dark mud. Threw the patent log over; temperature of the air, 95°; of the water, 85°.

A SALT BROOK

This shallow bay is mentioned in Joshua, xv. 2: Everything said in the Bible about the sea and the Jordan, we believe to be fully verified by our observations.

At 11:20, picked up a dead quail, which had probably perished in attempting to fly over the sea; perhaps caught in last night’s sirocco. At 11:28, there were appearances of sand-spits on the surface of the sea, doubtless the optical delusion which has so often led travelers to mistake them for islands. 11:30, sent the Fanny Skinner to Point Molyneaux, the south end of the peninsula, to take meridian observation. 12:30, much frothy scum upon the water. At 12:52, landed at Wady Muhariwat (Surrounded ravine), on the western shore, where a shallow salt stream, formed by a number of springs oozing from a bank covered with shrubs, spread itself over a considerable space, and trickled down over the pebbles into the sea. There were some very small fish in the stream. Thermometer, 96°.

At 1:15 P.M., started again, and steered parallel with the western shore. Keeping about one-third the distance between the western shore and the peninsula, the soundings ranged steadily at two and a quarter fathoms; first part light, the second part dark mud. At 3:05, a very singular swell from north-west, — an undulation, rather; for the waves were glassy, with an unbroken surface, and there was not air enough stirring to move the gossamer curls of a sleeping infant. We knew well of what it was the precursor, and immediately steered for the land. We had scarcely rowed a quarter of an hour, the men pulling vigorously to reach the shelter of the cliffs, when we were struck by a violent gust of hot wind, — another sirocco.

SCANTY PROVISIONS

The surface of the water became instantly ruffled; changing in five minutes from a slow, sluggish, unbroken swell, to an angry and foaming sea. With eyes smarting from the spray, we buffeted against it for upwards of an hour, when the wind abruptly subsided, and the sea as rapidly became smooth and rippling. The gust was from the north-west. The wind afterwards became light and baffling, — at one moment fair, the next directly ahead; the smooth surface of the water unbroken, except a light ruffle here and there, as swept by the flickering airs.

At 4:15 P.M., stopped for the night in a spacious bay, on a fine pebbly beach, at the foot of Rubtât el Jâmûs (Tying of the Buffalo). It was a desolate-looking, verdureless range above us. There was no water to be found, and our provisions were becoming scarce; we made a scanty supper, but had the luxury of a bed of pebbles, which, although hard and coarse, was far preferable to the mud and dust of our last sleeping-place. We hoped, too, to have but a reasonable number of insect-bedfellows.

Lieut. Dale described the extreme point of the peninsula upon which he landed as a low flat, covered with incrustations of salt and carbonate of lime. It was the point of the margin: there was a corresponding point to the high land, which is thinly laminated with salt. They picked up some small pieces of pure sulphur. In a cave, he saw tracks of a panther. After leaving the point, he saw a small flock of ducks and a heron, which were too shy to permit a near approach.

Before retiring, our Arabs, who had gone for hours in a fruitless search for water, returned with some dhom apples (fruit of the nubk), which amazingly helped out the supper.

REFRACTION

I do not know what we should have done without these Arabs; they brought us food when we were nearly famished, and water when parched with thirst. They acted as guides and messengers, and in our absence faithfully guarded the camp. A decided course tempered with courtesy, wins at once their respect and good will. Although they are an impetuous race, not an angry word had thus far passed between us. With the blessing of God, I hoped to preserve the existing harmony to the last. Took observations of Polaris. The north-west wind, hot and unrefreshing, sprang up at 8 P.M., and blew through the night. At 10, thermometer 84°; at midnight, 82°.

FRIDAY, APRIL 28. Called all hands at 5:30 A.M.; light airs from N.E., sky clouded, cirro-cumulus. Breakfasted à la hate on a small cup of coffee each, and started at 5:58. If the wind should spring up fair, we purposed sailing over to the Arnon; in the mean time we coasted along the shore towards Ain Jidy, for the water was exhausted, and we must make for the camp if a calm or a head wind should prevail. At 7:30, the wind freshened up from N.E. A little north of Sebbeh we passed a long, low, gravelly island, left uncovered by the retrocession of the water. A great refraction of the atmosphere. The Fanny Skinner, round the point, seemed elevated above it. Her whole frame, from the surface of the water, was distinctly visible, although the land intervened. At 12, wind fresh, air 87°, water 82°. Our compass glass was incrusted with salt.

Notwithstanding the high wind, the tendency to drowsiness was almost irresistible. The men pulled mechanically, with half-closed lids, and, except them and myself, every one in the copper boat was fast asleep. The necessity of steering and observing all that transpired, alone kept me awake. The drowsy sensation, amounting almost to stupor, was greatest in the heat of the day, but did not disappear at night. In the experience of all, two hours’ watch here seemed longer than double the period, elsewhere. At 1:30 P.M., nearly up with Ain Jidy; the white tents of the camp, the line of green, and the far-off fountain, speaking of shade, refreshment, and repose. A camel was lying on the shore, and two Arabs a little beyond. Discerning us, the latter rose quickly and came towards the landing, shouting, singing, and making wild gesticulations, and one of them stooped and picked up a handful of earth and put it upon his head. Here the Sherîf met us with a delight too simple-hearted in its expression to be insincere. The old man had been exceedingly anxious for our safety, and seemed truly overjoyed at our return. We were also much gratified to find that he had been unmolested.

One of the Arabs whom we sent back from Usdum fell fainting on his return, and nearly famished for want of water. His companions, suffering from the same cause, were compelled to leave him on the parched and arid shore and hasten forward to save themselves. Fortunately there was a messenger in the camp, who had come on horseback from Jerusalem, and Sherîf was enabled to send water forthwith, and have the poor man brought to the tents.

INTELLIGENCE FROM HOME

Found letters awaiting us from Beïrût, forwarded express from Jerusalem. Our consul at the former place announced the death of John Quincy Adams, (b.1767-d.1848) Ex-President of the United States,(1825–1829) and sent an extract from a Malta paper containing the annunciation. These were the first tidings we had received from the outer world, and their burthen was a sad one. But on that sea the thought of death harmonized with the atmosphere and the scenery, and when echo spoke of it, where all else was desolation and decay, it was hard to divest ourselves of the idea that there was nothing but death in the world, and we the only living. We lowered the flag half-mast, and there was a gloom throughout the camp.

TIDINGS FROM EUROPE

Among the letters, I received one from the Mushir of Saida. After many compliments, he promised to reprimand Sa’id Bey for the grasping spirit he had evinced, and authorized our ally, ’Akil, to remain with us as long as we might desire.

The very friendly letter of the American consul at Beïrût, Mr. Jasper Chasseaud contained startling news from Europe. The great Being who wisely rules over all, is doubtless punishing the nations for their sins; but, as His justice is ever tempered with mercy, I have not the smallest doubt that when the ordeal is passed, the result will be beneficial to the human race. The time is coming — the beginning is even now — when the whole worthless tribe of kings, with all their myrmidons, will be swept from their places and made to bear a part in the toils and sufferings of the great human family; — when, not in theory only, but in fact, every man will be free and all men politically equal; — then, this world will be a happy one, for liberty, rightly enjoyed, brings every blessing with it.

In the evening we walked up the ravine to bathe. It was a toilsome walk over the rough debris brought down by the winter rains. A short distance up, we were surprised to see evidences of former habitations in the rocks. Roughly hewn caverns and natural excavations we had frequently observed, but none before evincing so much art. Some of the apertures were arched and cased with sills of limestone resembling an inferior kind of marble.

AN EGERIAN FOUNTAIN

We were at a loss how to obtain an entrance, for they were cut in the perpendicular face of the rock, and the lowest more than fifty feet from the bed of the ravine. We stopped to plan some mode of gaining an entrance to one of them; but the sound of the running stream, and the cool shadow of the gorge were too inviting, and advancing through tamarisk, oleander, and cane, we came upon the very Egeria of fountains. Far in among the cane, embowered, imbedded, hidden deep in the shadow of the purple rocks and the soft green gloom of luxuriant vegetation, lapsing with a gentle murmur from basin to basin, over the rocks, under the rocks, by the rocks, and clasping the rocks with its crystal arms, was this little fountain-wonder. The thorny nubk and the pliant osher were on the bank above; yet lower, the oleander and the tamarisk; while upon its brink the lofty cane, bent by the weight of its fringe-like tassels, formed bowers over the stream fit for the haunts of Naiads. Diana herself could not have desired a more secluded bath than each of us took in a separate basin.

This, more probably than the fountain of Ain Jiddy (Engaddi), high up the mountain, may be regarded as the realization of the poet’s dream — the genuine “diamond of the desert” — and in one of the vaulted caves above, the imagination can dwell upon the night procession, Edith Plantagenet, and the flower dropped in hesitation and picked up with avidity; the pure, disinterested aspirations of the Crusader, the licentious thoughts of the Saracen, and the wild, impracticable visions of the saintly enthusiast. One of those caverns too, since fashioned by the hand of man, may have been the veritable cave of “Adullam,” for this is the wilderness of Engaddi. Here too may have been the dwellings of the Essenes, in the early days of Christianity, and subsequently of hermits, when Palestine was under Christian sway. Our Arabs say that these caves have been here from time immemorial, and that many years ago some of the tribe succeeded in entering one of them, and found vast chambers excavated in the rock. They may have been the cells where “gibbered and moaned” the hermit of Engaddi.

UNWONTED ENJOYMENT

Having bathed, we returned much refreshed to the camp. The messenger had brought sugar and lemons, and, with abundance of water, we had lemonade and coffee; and, sheltered from the sun, with the wind blowing through the tent, we revelled in enjoyment. This place, which at first seemed so dreary, had now become almost a paradise by contrast. The breeze blew freshly, but it was so welcome a guest, after the torrid atmosphere of noon, that we even let it tear up the tent stakes, and knock the whole apparatus about our ears, with a kind of indulgent fondness, rather disposed to see something amusing in the flutter among the half-dried linen on the thorn-bushes. This reckless disregard of our personal property bore ample testimony to our welcome greeting of the wind.

At one time, to-day, the sea assumed an aspect peculiarly sombre. Unstirred by the wind, it lay smooth and unruffled as an inland lake. The great evaporation enveloped it in a thin, transparent vapour, its purple tinge contrasting strangely with the extraordinary colour of the sea beneath, and, where they blended in the distance, gave it the appearance of smoke from burning sulphur. It seemed a vast cauldron of metal, fused but motionless.

About sunset, we tried whether a horse and a donkey could swim in the sea without turning over. The result was that, although the animals turned a little on one side, they did not lose their balance. As Mr. Stephens tried his experiment earlier in the season, and nearer the north end of the sea, his horse could not have turned over from the greater density of the water there than here. His animal may have been weaker, or, at the time, more exhausted than ours. A muscular man floated nearly breast-high, without the least exertion.

Pliny says that some foolish, rich men of Rome had water from this sea conveyed to them to bathe in, under the impression that it possessed medicinal qualities. Galen remarked on this that they might have saved themselves the trouble, by dissolving, in fresh water, as much salt as it could hold in solution; to which Reyland adds, that Galen was not aware that the water of the Dead Sea held other things besides salt in solution.

We picked up a large piece of bitumen on the sea-shore to-day. It was excessively hot to the touch. This combustible mineral is so great a recipient of the solar rays, that it must soften in the intense heat of summer. We gathered also some of the blossoms and the green and dried fruits of the osher [1] for preservation with the flowers collected in the descent of the Jordan, and the various places we have visited on this sea.

The dried fruit, the product of last year, was extremely brittle, and crushed with the slightest pressure. The green, half-formed fruit of this year was soft and elastic as a puff-ball, and, like the leaves and stem, yields a viscous, white, milky fluid when cut. Dr. Robinson very aptly compared it to the milk-weed. This viscous fluid the Arabs call leben-usher (osher-milk), and they consider it a cure for barreness. Dr. Anderson was enthusiastic in his researches, and although he kept his regular watch, was ever, when not on post, hammering at the rocks. He had already collected many valuable specimens.

Through the night, a pleasant breeze from the west. Blowing over the wilderness of Judea, it was unaccompanied with a nauseous smell. Towards morning, the wind hauled to the north and freshened-strange that the weather should become warmer as the wind veered to the northern quarter: but so it was. Sweeping along the western shore, it brought the foetid odour of the sulphureous marshes with it. The Arabs call this sea Bahr Lût (Sea of Lot), or Birket Lût (Pool of Lot).

[1]

This fruit is doubtless the genuine Apple of Sodom, for it is fair to the eye and bitter to the taste, and when ripe is filled with fibre and dust. Four jars, containing specimens, together with a drawing of the leaf and blossom, are placed in the patent-office, at Washington.

We have succeeded in bringing safely home some of the green and the dried fruit, and also the leaves and blossoms of the osher, put up in spirits of wine.

“The first notice taken of the apple of Sodom is by Josephus: — ‘Which fruits have a colour as if they were fit to be eaten; but if you pluck them with your hands, they dissolve into smoke and ashes.’ They are also spoken of by Tacitus:— ‘The herbage may spring up, and the trees may put forth their blossoms, they may even attain the usual appearance of maturity, but with this florid outside, all within turns black and moulders into dust.’

De Chartres, who visited Palestine in 1100, speaks of this fruit, and compares its deceitful appearance to the pleasures of the world; and they are also noticed by Baumgarten, De la Valle, Maundrell, and others, as having a real existence; but Pococke and Shaw deride these accounts as fabulous.

In the last century, Amman describes them as resembling a small apple, of a beautiful colour, and growing on a shrub resembling the hawthorn. Hasselquist, on the contrary, is of opinion that it is the fruit of the solanum melongena, or egg-plant.

He says that 'it is found in great abundance collected in the descent of the Jordan, and the various places round Jericho, in the valleys near the Jordan, and in the neighbourhood of the Dead Sea. It is true that these apples are sometimes full of dust, but this appears only when the fruit is attacked by an insect, which converts the whole of the inside into dust, leaving nothing but the rind entire, without causing it to lose any of its colour.’

Linnaeus thought, also, that they were the fruit of a solanum, and named a species having large yellow berries, with black seeds, surrounded by a greenish pulp, which dries into a bitter, nauseous powder, solanum Sodomeum; but it has been found that this plant is a native of Southern Africa, and not of Palestine.

Some writers, again, have supposed this fruit to be the gall of the terebinth, or turpentine-tree. Chateaubriand speaks of it as about the size and colour of a small lemon, which, before it is ripe, is filled with a corrosive and saline juice, and when dried, contains only numerous blackish seeds, which may be compared to ashes, and in taste resemble bitter pepper. He states that they are the product of a thorny shrub, having taper leaves.

In the travels of the Duke of Ragusa (Marmont), it is spoken of much in the same terms. These descriptions apply to a species of solanum, and especially to the s. sanctum, a prickly, shrub-like plant, very common in Palestine.

Seetzen, who does not appear to have seen the plant, says, ‘I saw, during my stay at Kerak, in the house of the Greek clergyman of that town, a species of cotton, resembling silk. This cotton, as he told me, grows in the plain of El Ghor, near the southern extremity of the Dead Sea, on a tree like the fig-tree, called Abesche-iz; it is found in a fruit resembling the pomegranate. It struck me that this fruit, which has no pulp or flesh in the inside, and is unknown in the rest of Palestine, might be the celebrated apple of Sodom.’

This description of Seetzen’s agrees very well with the fruit described as the apple of Sodom, which occurred in the same place, and has the same silky or cotton-like interior: but the plant which produces it is not like the fig-tree, nor is it called Abesche-iz.

Those we saw, in various places along the shores of the Dead Sea, resembled very closely the milkweed, which is so common in the United States; it is, in fact, a closely allied plant, being the asclepias procera of the earlier writers, now, however, forming part of the genus calotropis. This plant occurs in many parts of the east, and was known as early as the time of Theophrastus. It is figured and described by Prosper Alpinus under the name, birdet el ossar; but it is now called, by the Arabs, oscher, or osher.

It is a tall, perennial plant, with thick, dark-green, shining, opposite leaves, on very short foot-stalks; the flowers are interminal, and have axillary umbels of a purple colour, succeeded by somewhat globose pods, about the size of a large apple, containing numerous flattened, brown seeds, each furnished with a silky plume or pappus. The bark, especially at the lower part of the stem, is cork-like and much fissured. If it be cut, or a leaf torn off, a viscous, milky juice exudes, which is exceedingly acrid, and even caustic, and is said to be used in Egypt as a depillatory. In Persia, this plant is said to exude a bitter and acrid manna, owing to the puncture of insects. Chardin says that it is poisonous. Both the plant and its juice have been used in medicine, and probably are identical with the mudar, or madar, of India, which has attracted so much notice as a remedy for diseases of the skin” — Griffith.