The American Indian/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII

SPECIAL INVENTIONS

There remain a great array of culture traits we have not noted, such as machinery, fire-making, lamps, weapons, musical instruments, fermentation, glues and cements, paper, dyes and paints, woodwork, maps, astronomical knowledge, writing, poisons, medicine, surgery and anatomical knowledge, etc. For descriptive details on these topics, the reader must turn to the standard books of reference. Few of these subjects have been developed to a point whereby significant problems arise and the only function their discussion could now serve would be the increasing of our wonder at the complexity of aboriginal life. Therefore, we shall refer to but a small number of them.

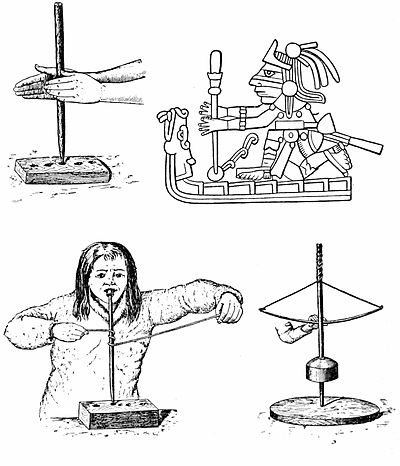

One of the more fundamental traits in which the old culture of Asia outstripped the New World was the development of the wheel and revolving machinery. Yet, we have noted the spindle whorl and find certain kinds of drills that embody a kind of wheel concept. However, among the Eskimo we find drills turned by a strap pulled back and forth and also operated by a strung bow. This gives a reciprocating motion which is the principle in old Asiatic drills and lathes.[1] The geographical position of the Eskimo makes it probable that we have in this a case of relatively recent borrowing from the Old World. The only other New World localities in which these forms of drilling occur are among the Northern Algonkin. From the native sketches in Mexican codices and the references of early writers, we infer that the universal mode of drilling was by rolling between the palms of the hands. Even the Peruvians seem never to have risen above this method. Yet, we have four problematic localities in which forms of the Old World pumpdrill occur: the Iroquois, Pueblos, Round Valley Indians of California and the North Pacific Coast. In the case of the former, we cannot be sure that this drill was not introduced by European colonists, and as archæological data from the Southwest give no trace of it, we may regard its

Fig. 59. Methods of Drilling. Tylor

presence there as of Spanish origin. Again, the California drill is operated on a slightly different principle, and its very limited distribution suggests its intrusion. If these forms of the pumpdrill are truly independent inventions, they are evidently recent, for they would with time have spread over large areas. In short, we are justified in assuming that the rotating tool or wheel had no place in the original mechanical concepts of the New World.

Perhaps one of the greatest discoveries ever made by man was that fire could be kindled at will. The great English anthropologist, Tylor, has given us a model study of fire-making.[2] It appears that in aboriginal times practically the whole of the New World kindled fire with the simple hand-drill.[3] Only among the Eskimo and a few of the adjoining Indians were other types of drill in use, as may be inferred from the preceding discussion. To strike fire from flint one must have good iron, preferably steel, hence, that method was unknown here; but nature provides a fair substitute in iron pyrites to which the Eskimo frequently resort and which is the prevailing method in the greater part of the caribou area. It is sometimes believed that this is intrusive from the Old World, but it is also the method in the guanaco area of South America, which suggests that the cause may be environmental.

Another invention of great significance is the art of writing. So far as we can tell, no form of writing was practised in South America, that achievement appearing to be a Maya contribution. The codices of Mexico and their official use at the time of the Conquest are a matter of common knowledge, but the more definite extinct Maya system of writing presents one of the great puzzles of our subject.[4] Some progress has been made in recovering the key to it, in so far as the calendar and dates are concerned. From these, it appears that the Maya system is both pictographic and phonetic and that the Mexican scheme was in the main derived from it.

North of Mexico the existence of true writing may be doubted. In the pictographic year counts of certain tribes of Plains Indians,[5] we find something faintly suggesting the Mexican codex, and in the birchbark ceremonial tablets of the Ojibway we have true picture writing. Yet, in no case did such picture writing become an accepted mode of communication, its function usually being merely to herald the deeds of the scribe. By this means, however, were developed a few conventional characters that were equivalent to hieroglyphs.[6]Yet, if the Inca of Peru did not have writing, they did have a scheme of knotted cords, or quipu, the methods of which have been inductively worked out by Locke.[7] From this study it appears that the quipu could have served no other purpose than that of recording numbers. In fact, from the Spanish authors and the modern survivals of these knotted cord records, we know that the quipu were used to keep accounts. Mr. Locke's careful study of specimens in the American Museum of Natural History of New York demonstrates that the numerical system upon which the quipu were based was decimal. Further, an empirical analysis of the knots on the several cords shows them to have definite numerical relations from which we infer that the quipu were instruments of enumeration only. It is scarcely conceivable that they could have been used for the recording of other facts. Hence, the oft-repeated statement that they were used to record historic narratives or as mnemonic systems for the same, are unwarranted.

Before leaving this subject, we should note one very remarkable achievement by the Maya. This was no less than the discovery and use of the zero in mathematics.[8] In the Old World, this important contribution to our culture was invented by an Asiatic people, probably a Hindu group, from whom it found its way into Europe. On the other hand, it appears in ancient Maya. The very isolation of these two discoveries suggests their independent invention, but irrespective of this interpretation, the use of the zero in the New World gives its people a high place in culture.

Though somewhat of a diversion, we may at this point note the making of bark cloth and paper. In Mexico, where writing was practised, good paper was made of amatl bark and, when this was not available, of maguey fiber. The latter was covered with thin animal membranes, reminding one of parchment. Outside of Mexico and Central America, no paper was used, but some bark garments were made in the forest regions of South America. In this connection an interesting point is raised by the ridged bark-beater of Mexico and Central America, an implement which reminds one of the tool used by the tapa makers of the Pacific Islands. Then, far up on the west coast of North America, the natives shred cedar bark for weaving by beating with a similar ridged tool. We have here another very puzzling problem arising from the scattered distribution of an industrial process.

Another item of importance is astronomical knowledge and methods of reckoning time. Of the South American system we know next to nothing, but that of the Maya excites our unbounded admiration. It is a veritable mathematical puzzle of the most ingenious kind.[9] That it was based upon careful astronomical study is clear from the corrections made for the odd five days in the year. The religion of the Maya, Nahua, and Inca was largely based upon star gods and the movements of the heavenly bodies, itself implying very exact astronomical knowledge.

North of Mexico, methods of reckoning time are very crude, though apparently strongest among the Pueblo and adjacent Plains tribes. Some of the latter kept moon counts by tally sticks and scored the years by winters, but this was quite perfunctory. So far as we know, the northern limits of this influence are near the Ohio River, the whole distribution suggesting that it is a phenomenon of diffusion from the centers of higher culture.

Perhaps the next most significant topic in our list is that of weapons. Some very engaging problems center around the bow, harpoon, spear, shield, sling, ax, sword, blowgun, and defensive armor. Practically all have been made the subjects of special study. Thus, defensive armor of wood and hide has been studied by Hough, who for one thing favors a Japanese origin for North American plate armor.[10] This subject has been more exhaustively treated by Laufer[11] who demonstrates the improbability of its Japanese origin since this type of armor appears in other parts of Asia before it was known in Japan, particularly among the wilder tribes, suggesting that we may yet find a much earlier historical connection between the plate armor of the New World and the Old. Yet, while it is true that wooden armor is found only on the upper Pacific side, cotton armor was worn in Mexico and in Peru, often reinforced with metal. In recent times, at least, some forms of armor were used by the Araucanians and Abipones of Chile and Argentina.

While shields of wicker and cane were widely used in the area of intense culture and in the eastern maize area, the small circular shield seems to have centered in Mexico. Among the Pueblo and Plains tribes, a similar shield of bison hide appears, whose decorations are quite like those of ancient Mexico. Since the restricted distribution of the circular

Fig. 60. Wooden Slat Armor, British Columbia. Teit, 1900. I

shield is geographically continuous, we may assume for it a single origin. In Peru, on the other hand, the shields were rectangular.

A case of some theoretical interest is the blowgun, found among the forest Indians of eastern South America, in the Antilles, and even in eastern United States, the Iroquois of New York being the most northern point in its distribution. The somewhat analogous distribution of this weapon in Asia gives us one of the most probable cases of independent invention.

Finally, we may turn to the bow. Its use appears to have been universal from the Eskimo of the North to the simple Fuegians of the South. Though in the historic horse culture of the guanaco area it was not used, the evidence for its former use there is generally considered as conclusive. However, the tendency of the great military cultures of Mexico and Peru seems to have been toward mass fighting hand to hand, with swords and clubs. We notice the same thing among the Haida and other strong tribes of the northwest coast. In other words, as in the Old World, it was the less organized, more nomadic peoples who made most effective use of the bow.

One point of particular interest is the sinew reinforced bow, the highest type of which is found in Asia.[12] In various forms it covers the highlands of North America well down into Mexico, but did not reach far into the eastern maize area. The Eskimo also had this bow in several forms, those of the West being more like the Asiatic type. Now, as this structural concept does not appear in South America,[13] we have the suggestion of an Asiatic intrusion. This does not, however, apply to the bow trait as a whole, for its distribution carries it into the most remote marginal areas, and along with it the notched arrow-head. Thus bow culture, in general, seems best explained as a trait brought in by the earliest visitors to the New World. Among the curiosities is the pellet-shooting bow of Brazil which has its parallel in Asia, frequently cited as another clear case of independent invention.