Hoyle's Games Modernized/Draughts

DRAUGHTS.

- "In friendly contention, the old men

- Laughed at each lucky hit or unsuccessful manœuvre—

- Laughed when a man was crowned, or a breach was made in the king-row."

- Longfellow—Evangeline.

The game of Draughts is played on a board of sixty-four squares of alternate colours, and with twenty-four pieces, called men (twelve on each side), also of opposite colours. It is played by two persons; the one having the twelve black or red pieces is technically said to be playing the first side, and the other, having the twelve white, to be playing the second side. Each player endeavours to confine the pieces of the other in situations where they cannot be played, or both to capture and fix, so that none can be played; the person whose side is brought to this state loses the game.

The essential rules of the game are as under—

The board shall be so placed that the bottom corner square on the left hand shall be black.

The men shall be placed on the black squares.[107]

The black men shall be placed upon the supposed first twelve squares of the board; the white upon the last twelve squares.

Each player shall play alternately with black and white men. Lots shall be cast for the colour at the commencement of a match, the winner to have the choice of taking black or white.

The first move must invariably be made by the person having the black men.

At the end of five minutes "Time" may be called; and if the move be not completed on the expiry of another minute, the game shall be adjudged lost through improper delay.

When there is only one way of taking one or more pieces, "Time" shall be called at the end of one minute; and if the move be not completed on the expiry of another minute, the game shall be adjudged lost through improper delay.

After the first move has been made, if either player arrange any piece without giving intimation to his opponent, he shall forfeit the game; but, if it is his turn to play, he may avoid the penalty by playing that piece, if possible.

After the pieces have been arranged, if the person whose turn it is to play touch one, he must either play that piece or forfeit the game. When the piece is not playable, he is penalised according to the preceding law.

If any part of a playable piece be played over an angle of the square on which it is stationed, the play must be completed in that direction.

A capturing play, as well as an ordinary one, is completed the moment the hand is withdrawn from the piece played, even though two or more pieces should have been taken.

When taking, if a player remove one of his own pieces, he cannot replace it, but his opponent can either play or insist on his replacing it.

Either player making a false or improper move shall forfeit the game to his opponent, without another move being made.

The "Huff" or "Blow" is, before one plays his own piece, to remove from the board any of the adverse pieces that might or should have taken. The "Huff" does not constitute a move.

The player has the power either to huff, compel the take, or to let the piece remain on the board, as he thinks proper.[108]

When a man first reaches any of the squares on the opposite extreme line of the board, it becomes a "King." It must be crowned (by placing a man of the same colour on the top of it) by the opponent, and can afterwards be moved backwards or forwards as the limits of the board permit.

A Draw is when neither of the players can force a win. When one of the sides appears stronger than the other, the stronger party may be required to complete the win, or to show a decided advantage over his opponent within forty of his own moves—counted from the point at which notice was given—failing in which, he must relinquish the game as a draw.

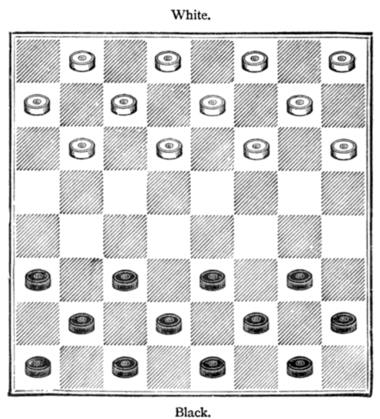

Fig. 1.

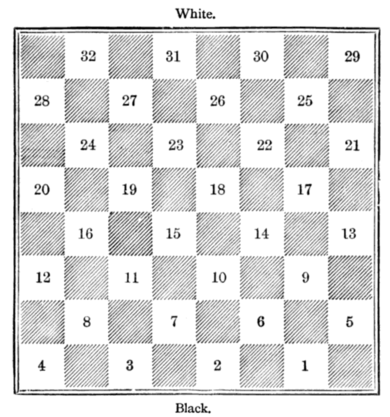

The above diagram (Fig. 1) shows the board set for play, and Fig. 2 shows the draught-board numbered for the purpose of recording moves.

Fig. 2.

The men being placed as shown in Fig. 1, the game is begun by each player moving alternately one of his men along the diagonal on which it is situated. The men can only move forward either to right or left one square at a time, unless they have attained one of the four squares on the extreme further side of the board (technically termed the "crown-head"). This done, they become Kings, and can move either forward or backward. The pieces take in the direction they move, by leaping over any opposing man that may be immediately contiguous, provided there be a vacant square behind it. If several men should be exposed by having open spaces behind them alternately, they may be all taken at one capture, and the capturing piece is then placed on the square beyond the last man.

To explain the mode of capturing by a practical illustration, let us begin by placing the men as for a game. You will perceive that Black, who always plays first, can only move one of the men placed on 9, 10, 11, or 12; supposing him, then, to play the man on 11 to 15, and White to answer this by playing 22 to 18, Black can take the white man on 18 by leaping from 15 to 22, and removing the captured piece from the board. Should Black not take the man on 18, but make another move—say 12 to 16, for instance—he is liable to be "huffed"; that is, White may remove the man (that on 15) with which Black should have taken, off the board for not taking. When one party "huffs" the other in preference to compelling the take, he does not replace the piece his opponent moved, but simply removes the man huffed from the board, and then plays his own move.

General Advice.

It is generally better to keep your men in the middle of the board than to play them to the side squares, as in the latter case one-half of their power is curtailed.

When you have once gained an advantage in the number of your pieces, you increase the proportion by exchanges, but in forcing them you must take care not to damage your position. Open your game at all times upon a regular plan; by so doing you will acquire method in both attack and defence. Accustom yourself to play slowly at first, and, if a beginner, prefer playing with better players than yourself. Note their methods of opening a game, and follow them when opportunity presents itself.

If playing against an inferior, it is as well to keep the game complicated; if with a superior, to simplify it. Avoid scattering your forces; as they get fewer, concentrate them as much as possible.

Never touch the squares of the board with your fingers; and accustom yourself to play your move off-hand, when you have once made up your mind.

Do not lose time in studying when you have only one way of taking, but take quickly.

Pay quite as much attention to the probable plans of your adversary as to your own.

Remember that the science of the game consists in so moving your pieces at the commencement as to obtain a position which will compel your adversary to give his men away. One man ahead with a clear game should be a certain win.

In conclusion, the student is strongly advised to study and master the theory and practice of the play embraced in the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Positions (see post). These endings, in different forms, are of very frequent occurrence, and should be thoroughly mastered.

The Names of the Various Openings And How Formed.

1. The "Ayrshire Lassie" is formed by the first four moves (counting the play on both sides): 11 to 15, 24 to 20, 8 to 11, 28 to 24.

2. The "Bristol" is formed by the first three moves: 11 to 16, 24 to 20, 16 to 19. It was so named in compliment to the players of that city for services rendered to the late Andrew Anderson, one of the greatest masters of the game.

3. The "Cross" is formed by the first two moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 18. It is so named because the second move is played across the direction of the first.

4. The "Defiance" is formed by the first four moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 9 to 14, 27 to 23. It is so named because it defies or prevents the formation of the "Fife" game.

5. The "Dyke" is formed by the first three moves: 11 to 15, 22 to 17, 15 to 19.

6. The "Fife" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 9 to 14, 22 to 17, 5 to 9. It has been so called since 1847, when Wyllie, hailing from Fifeshire, played it against Anderson.

7. The "Glasgow" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 8 to 11, 22 to 17, 11 to 16. It has been known by this name since Sinclair, of Glasgow, played it against Anderson at a match in 1828.

8. The "Laird and Lady" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 8 to 11, 22 to 17, 9 to 13. It was so called from its having been the favourite opening of Laird and Lady Cather Cambusnethan, Lanarkshire.

9. "The Maid of the Mill" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 22 to 17, 8 to 11, 17 to 13, 15 to 18. It was so named in compliment to a miller's daughter, who was an excellent player, and partial to this opening.

10. The "Old Fourteenth" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 8 to 11, 22 to 17,4 to 8. It was so named through being familiar to players as the fourteenth game in Joshua Sturge's Guide to the Game of Draughts, published in 1800, which for many years was the leading authority on the game.

11. The "Second Double Corner" is formed by the first two moves: 11 to 15, 24 to 19. It is so named because the first move of the second player is from the one double corner towards the other.

12. The "Single Corner" is formed by the first two moves: 11 to 15, 22 to 18. It is so named from the fact of each of these moves being played from one single corner towards the other.

13. The "Souter" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 9 to 14, 22 to 17, 6 to 9. The game was so named owing to its being the favourite of an old Paisley shoemaker (Scotticé, souter).

14. The "Whilter" is formed by the first five moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 9 to 14, 22 to 17, 7 to 11. "Whilter" or "Wholter," in Scotch, signifies an overturning, or a change productive of confusion.

15. The "Will-o'-the-Wisp" is formed by the first three moves: 11 to 15, 23 to 19, 9 to 13.

N.B.—The reader should observe, in studying the position following, that the numbering of the squares always starts from the black side of the board, whether black occupy the upper or the lower rows.

END GAMES.

Two Kings To One.

Position.

![Fig. 3. [White to Move and Win.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2e/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_436.png/380px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_436.png)

[White to Move and Win.]

Fig. 3.

[White to Move and Win.]

To win with two Kings against one in the double corner (see Fig. 3) is often a source of difficulty to the learner, and yet, once known, nothing is more simple. The following shows how to force the win:

Solution.

|

22.18 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

Three Kings To Two.

This, again, is a state of things of very frequent occurrence, and the novice, even with the stronger game, may find it somewhat difficult to deal with.

The proper course for White is either to pin one of Black's men, and then go for the other, or to force an exchange, so as to be left with two Kings to one, when the game, as we have seen, is a foregone conclusion. To avoid this, Black naturally endeavours to reach the two double corners, so as to have his men as far apart as possible, and to divide the attacking force. Where Black adopts these tactics the proper play, on the part of White, is to get his three Kings in a line on the same diagonal as Black's two. Thus, if Black is at 32 and 5, White must manœuvre to place his men upon squares 23, 18 and 14. If Black occupies 28 and 1, White must secure 19, 15 and 10. In this position, however Black may play, he is compelled, on White's next move, to accept the offer of an exchange. White has then two Kings to one, and the game is practically at an end.

Position.

![Fig. 4. [White to Move and Win.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_438.png/380px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_438.png)

[White to Move and Win.]

Fig. 4.

[White to Move and Win.]

The Elementary Positions.

There are four often recurring situations known as the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Positions. It is highly desirable that the student should make himself well acquainted with them.

First Position.

![Fig. 5. [Black to Move and Win.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_439.png/380px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_439.png)

[Black to Move and Win.]

Fig. 5.

[Black to Move and Win.]

Solution.

|

27.32 |

6.1 |

14.18 |

9.14 |

Variation 1.

|

30.25 |

22.18 |

5.9 |

15.18 |

Variation 2.

|

9.14 |

17.13 |

Continue as |

Second Position.

![Fig. 6. [Black to Move and Win.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/49/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_441.png/380px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_441.png)

[Black to Move and Win.]

Fig. 6.

[Black to Move and Win.]

Solution.

|

5.9 |

23.18 |

14.10 |

Third Position.

![Fig. 7. [Black to Move and Win.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_443.png/370px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_443.png)

[Black to Move and Win.]

Fig. 7.

[Black to Move and Win.]

Solution.

|

13.9 |

14.18 |

11.15 |

Variation 1.

|

14.18 |

10.15 |

26.31 |

Variation 2.

|

14.17 |

5.14 |

25.21 |

Variation 3.

|

14.10 |

10.14 |

14.9 |

Variation 4.

|

22.18 |

22.26 |

22.26 |

- B. wins. Very critical, and requires extreme care in forcing the win.

Fourth Position.

![Fig. 8. [Black to Move and Win.] [White to Move and Draw.]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Hoyles_Games_Modernized_445.png/380px-Hoyles_Games_Modernized_445.png)

[Black to Move and Win.]

[White to Move and Draw.]

Fig. 8.

[Black to Move and Win.]

[White to Move and Draw.]

Solution.

|

28.24 |

32.27 |

31.27 |

22.18 |

For further information as to the science of the game, see the article "Draughts" in The Book of Card and Table Games, of which the above account is an abridgment. The reader desirous of still more minute information will find it in The Game of Draughts Simplified, by Andrew Andersen. The fifth edition (1887) of this standard work (James Forrester, 2s. 6d.) is edited by Mr. Robert McCulloch, the writer of the above-mentioned article. Mr. McCulloch has also produced a book of his own, The Guide to the Game of Draughts (Bryson & Co., Glasgow, 2s. 6d.). These are thoroughly up-to-date publications. We may mention in addition the American Draughtplayer, by H. Spayth, the accepted authority in America, and two valuable works by Mr. Joseph Gould, The Problem Book, and Match Games.

- 107 ↑ In England it was formerly the custom to play on the white squares, but the Scottish practice of using the black squares is now generally adopted. So far as the course of play is concerned, the one plan is as good as the other; and in all treatises on the game the men are, for typographical reasons, shown on the white squares. This involves a corresponding alteration of the position of the board, which is shown with a white bottom square on the left hand.

- 108 ↑ A player may be huffed for not taking the full number of men he should have taken by the play adopted. Thus if he takes one man only, where by the same play, duly continued, he could have taken two, he is liable to the huff. If, however, he has the choice of two moves, by one of which he would take a larger number of men taken than by the other, he is under no obligation to adopt that move.