CRITICISMS AND LISTS BY THE BEST JUDGES.

II—H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, Politicians, &c.

WE begin the criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list with the letter of the Prince of Wales, whose interest in the advancement of letters is well known, and who courteously found time to answer our questions.

H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES.

My dear Sir,—I am desired by the Prince of Wales to thank you for your letter of the 11th inst., and to assure you that he appreciates very sincerely the compliment which you are so good as to pay him in requesting him to draw up a catalogue of books which might seem to him to be the most conducive to a healthy mental state. The application is one which would require much time and thought to answer satisfactorily, and the Prince speaks, therefore, with diffidence when he expresses an opinion that the list suggested by Sir John Lubbock could hardly be improved upon. His Royal Highness would, however, venture to remark that the works of Dryden should not be omitted from such an important and comprehensive list.—I beg to remain, yours truly, Francis Knollys.

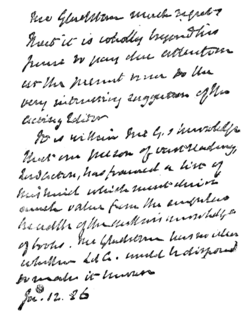

MR. GLADSTONE.

The late Prime Minister is like the Prince of Wales in at least one respect—both of them are men of encyclopædic interests. Mr. Gladstone is well known to be an omnivorous reader, and he was naturally among the first of the judges to whom we forwarded Sir John Lubbock's list. Mr. Gladstone replied by return of post, and on a post card, as follows:—

The general public were able to form some idea of Lord Acton's "vast reading" from his review of George Eliot's Life some months ago in the Nineteenth Century, and we hoped to have been able to lay before our readers the information to which Mr. Gladstone so properly attaches such high importance. Unfortunately, however, Lord Acton was abroad, and our letter did not reach him until after a considerable interval. He very kindly promised to write to us on the subject, but his letter has not reached us in time to be included in the present issue.

MR. CHAMBERLAIN.

Sir,—In reply to your inquiry I am directed by Mr. Chamberlain to say that he does not think he could greatly improve the list of books already submitted by Sir John Lubbock. He would, however, inquire whether it is by accident or design that the Bible has been omitted.—I am, yours obediently, Wm. Woodings.

PROFESSOR BRYCE, M.P.

The new Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs has made himself so much of a political reputation in these latter years that we include him under the head of politicians. People are almost beginning to forget that he first made his reputation by a book ("The Holy Roman Empire"), and that he is still a University professor. Mr. Bryce wrote to us as follows:—

I am sorry to have been prevented by an accumulation of work from replying sooner to your request for a list of books "necessary for a liberal education," such as you have had from Sir John Lubbock. I have not time to furnish you with such a list, which would need a good deal of consideration, and would be quite different according as one assumes the person to be "liberally educated" to possess a wider or narrower knowledge of languages. There are books well deserving to be read in the original which are much less worth reading in translations.

However, I give you some additions to and criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list which occur to me. I have not seen the remarks of your other correspondents, except Mr. Ruskin's. In Greek poetry Pindar ought to be substituted for Hesiod. In Greek philosophy Aristotle's Rhetoric and Poetic ought not to be omitted. Of Cicero it would be much better to have some Orations than the Offices or Old Age. St. Augustine's "De Civitate Dei" is indispensable. Perhaps no book ever more affected history. "The Icelandic Sagas," or some of them, ought to be added. Most of the best have been translated, such as "Njál's Saga," "Grettir's Saga," and the "Heimskringla." The poems in the "Elder Edda" (now admirably translated in Vigfusson and Powell's "Corpus Poeticum Boreale") ought also to find a place. For travels, add Marco Polo; for history, Machiavelli's "Prince." In Italian poetry Ariosto and Leopardi should come in. The "Lusiad" of Camoens is one of