Life of William Blake (1880), Volume 1/Chapter 1

From nearly all collections or beauties of 'The English Poets,' catholic to demerit as these are, tender of the expired and expiring reputations, one name has been hitherto perseveringly exiled. Encyclopædias ignore it. The Biographical Dictionaries furtively pass it on with inaccurate despatch, as having had some connexion with the Arts. With critics it has had but little better fortune. The Edinburgh Review, twenty-seven years ago, specified as a characteristic sin of 'partiality' in Allan Cunningham's pleasant Lives of British Artists, that he should have ventured to include this name, since its possessor could (it seems) 'scarcely be considered a painter' at all. And later, Mr. Leslie, in his Handbook for Young Painters, dwells on it with imperfect sympathy for a while, to dismiss it with scanty recognition.

Yet no less a contemporary than Wordsworth, a man little prone to lavish eulogy or attention on brother poets, spake in private of the Songs of Innocence and Experience of William

Of his Designs, Fuseli and Flaxman, men not to be imposed on in such matters, but themselves sensitive—as Original Genius must always be—to Original Genius in others, were in the habit of declaring with unwonted emphasis, that 'the time would come' when the finest 'would be as much sought after and treasured in the portfolios' of men discerning in art, 'as those of Michael Angelo now.' 'And ah! Sir,' Flaxman would sometimes add, to an admirer of the designs, 'his poems are as grand as his pictures.'

Of the books and designs of Blake, the world may well be ignorant. For in an age rigorous in its requirement of publicity, these were in the most literal sense of the words, never published at all: not published even in the mediæval sense, when writings were confided to learned keeping, and works of art not unseldom restricted to cloister-wall or coffer-lid. Blake's poems were, with one exception, not even printed in his life-time; simply engraved by his own laborious hand. His drawings, when they issued further than his own desk, were bought as a kind of charity, to be stowed away again in rarely opened portfolios. The very copper-plates on which he engraved, were often used again after a few impressions had been struck off; one design making way for another, to save the cost of new copper. At the present moment, Blake drawings, Blake prints, fetch prices which would have solaced a life of penury, had their producer received them. They are thus collected, chiefly because they are (naturally enough) already 'RARE,' and 'VERY RARE.' Still hiding in private portfolios, his drawings are there prized or known by perhaps a score of individuals, enthusiastic appreciators,—some of their singularity and rarity, a few of their intrinsic quality.

At the Manchester Art-Treasures Exhibition of 1857, among the select thousand water-colour drawings, hung two modestly tinted designs by Blake, of few inches in size: one the Dream of Queen Catherine, another Oberon and Titania. Both are remarkable displays of imaginative power, and finished examples in the artist's peculiar manner. Both were unnoticed in the crowd, attracting few gazers, fewer admirers. For it needs to be read in Blake, to have familiarized oneself with his unsophisticated, archaic, yet spiritual 'manner,'—a style sui generis as no other artist's ever was,—to be able to sympathize with, or even understand, the equally individual strain of thought, of which it is the vehicle. And one must almost be born with a sympathy for it. He neither wrote nor drew for the many, hardly for work'y-day men at all, rather for children and angels; himself 'a divine child,' whose play-things were sun, moon, and stars, the heavens and the earth.

In an era of academies, associations, and combined efforts, we have in him a solitary, self-taught, and as an artist, semi-taught Dreamer, 'delivering the burning messages of prophecy by the stammering lips of infancy,' as Mr. Ruskin has said of Cimabue and Giotto. For each artist and writer has, in the course of his training, to approve in his own person the immaturity of expression Art has at recurrent periods to pass through as a whole. And Blake in some aspects of his art never emerged from infancy. His Drawing, often correct, almost always powerful, the pose and grouping of his figures often expressive and sublime as the sketches of Raffaelle or Albert Dürer, on the other hand, range under the category of the 'impossible;' are crude, contorted, forced, monstrous, though none the less efficient in conveying the visions fetched by the guileless man from Heaven, from Hell itself, or from the intermediate limbo tenanted by hybrid nightmares. His prismatic colour, abounding in the purest, sweetest melodies to the eye, and always expressing a sentiment, yet looks to the casual observer slight, inartificial, arbitrary.

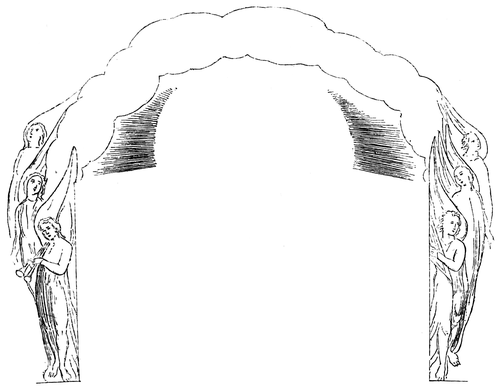

Many a cultivated spectator will turn away from all this as from mere ineffectualness,—Art in its second childhood. But see that sitting figure of Job in his Affliction, surrounded by the bowed figures of wife and friend, grand as Michael Angelo, nay, rather as the still, colossal figures fashioned by the genius of old Egypt or Assyria! Look on that simple composition of Angels Singing aloud for Joy, pure and tender as Fra Angelico, and with an austerer sweetness.

It is not the least of Blake's peculiarities that, instead of expressing himself, as most men have been content to do, by help of the prevailing style of his day, he, in this, as in every other matter, preferred to be independent of his fellows; partly by choice, partly from the necessities of imperfect education as a painter. His Design has conventions of its own; in part, its own, I should say, in part, a return to those of earlier and simpler times.

Of Blake as an Artist, we will defer further talk. His Design can ill be translated into words, and very inadequately by any engraver's copy. Of his Poems, tinged with the very same ineffable qualities, obstructed by the same technical flaws and impediments—a semi-utterance as it were, snatched from the depths of the vague and unspeakable—of these remarkable Poems, never once yet fairly placed before the reading public, specimens shall by-and-bye speak more intelligibly for themselves. Both form part in a Life and Character as new, romantic, pious—in the deepest natural sense—as they: romantic, though incident be slight; animated by the same unbroken simplicity, the same high unity of sentiment.