1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Buoy

BUOY (15th century “boye”; through O.Fr. or Dutch, from Lat. boia, fetter; the word is now usually pronounced as “boy,” and it has been spelt in that form; but Hakluyt’s Voyages spells it “bwoy,” and this seems to indicate a different pronunciation, which is also given in some modern dictionaries), a floating body employed to mark the navigable limits of channels, their fairways, sunken dangers or isolated rocks, mined or torpedo grounds, telegraph cables, or the position of a ship’s anchor after letting go; buoys are also used for securing a ship to instead of anchoring. They vary in size and construction from a log of wood to steel mooring buoys for battleships or a steel gas buoy.

In 1882 a conference was held upon a proposal to establish a uniform system of buoyage. It was under the presidency of the then duke of Edinburgh, and consisted of representatives from the various bodies interested. The questions of colour, visibility, shape and size were considered, and any modifications necessary owing to locality. The committee proposed the following uniform system of buoyage, and it is now adopted by the general lighthouse authorities of the United Kingdom:—

|

|

|

| Fig. 1. | Fig. 2. | Fig. 3. |

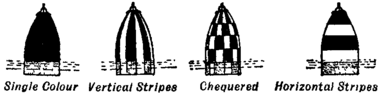

(1) The mariner when approaching the coast must determine his position on the chart, and note the direction of flood tide. (2) The term “starboard-hand” shall denote that side which would be on the right hand of the mariner either going with the main stream of the flood, or entering a harbour, river or estuary from seaward; the term “port-hand” shall denote the left hand of the mariner in the same circumstances. (3)[1] Buoys showing the pointed top of a cone above water shall be called conical (fig. 1) and shall always be starboard-hand buoys, as above defined. (4)[1] Buoys showing a flat top above water shall be called can (fig. 2) and shall always be port-hand buoys, as above defined. (5) Buoys showing a domed top above water shall be called spherical (fig. 3) and shall mark the ends of middle grounds. (6) Buoys having a tall central structure on a broad face shall be called pillar buoys (fig. 4), and like all other special buoys, such as bell buoys, gas buoys, and automatic sounding buoys, shall be placed to mark special positions either on the coast or in the approaches to harbours. (7) Buoys showing only a mast above water shall be called spar-buoys (fig. 5).[2] (8) Starboard-hand buoys shall always be painted in one colour only. (9) Port-hand buoys shall be painted of another characteristic colour, either single or parti-colour. (10) Spherical buoys (fig. 3) at the ends of middle grounds shall always be distinguished by horizontal stripes of white colour, (11) Surmounting beacons, such as staff and globe and others,[3] shall always be painted of one dark colour. (12) Staff and globe (fig. 1) shall only be used on starboard-hand buoys, staff and cage (fig. 2) on port hand; diamonds (fig. 7) at the outer ends of middle grounds; and triangles (fig. 3) at the inner ends. (13) Buoys on the same side of a channel, estuary or tideway may be distinguished from each other by names, numbers or letters, and where necessary by a staff surmounted with the appropriate beacon. (14) Buoys intended for moorings (fig. 6) may be of shape and colour according to the discretion of the authority within whose jurisdiction they are laid, but for marking submarine telegraph cables the colour shall be green with the word “Telegraph” painted thereon in white letters.

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 4. | Fig. 5. | Fig. 6. | Fig. 7. |

Buoying and Marking of Wrecks.—(15) Wreck buoys in the open sea, or in the approaches to a harbour or estuary, shall be coloured green, with the word “Wreck” painted in white letters on them. (16) When possible, the buoy should be laid near to the side of the wreck next to mid-channel. (17) When a wreck-marking vessel is used, it shall, if possible, have its top sides coloured green, with the word “Wreck” in white letters thereon, and shall exhibit by day, three balls on a yard 20 ft. above the sea, two placed vertically at one end and one at the other, the single ball being on the side nearer to the wreck; in fog a gong or bell is rung in quick succession at intervals not exceeding one minute (wherever practicable); by night, three white fixed lights are similarly arranged as the balls in daytime, but the ordinary riding lights are not shown. (18) In narrow waters or in rivers and harbours under the jurisdiction of local authorities, the same rules may be adopted, or at discretion, varied as follows:—When a wreck-marking vessel is used she shall carry a cross-yard on a mast with two balls by day, placed horizontally not less than 6 nor more than 12 ft. apart, and by night two lights similarly placed. When a barge or open boat only is used, a flag or ball may be shown in the daytime. (19) The position in which the marking vessel is placed with reference to the wreck shall be at the discretion of the local authority having jurisdiction. A uniform system by shape has been adopted by the Mersey Dock and Harbour Board, to assist a mariner by night, and, in addition, where practicable, a uniform colour; the fairway buoys are specially marked by letter, shape and colour.

| |||

| Fig. 8. | Fig. 9. | Fig. 10. | Fig. 11. |

British India has practically adopted the British system, United States and Canada have the same uniform system; in the majority of European maritime countries and China various uniform systems have been adopted. In Norway and Russia the compass system is used, the shape, colour and surmountings of the buoys indicating the compass bearing of the danger from the buoy; this method is followed in the open sea by Sweden. An international uniform system of buoyage, although desirable, appears impracticable. Germany employs yellow buoys to mark boundaries of quarantine stations. The question of shape versus colour, irrespective of size, is a disputed one; the shape is a better guide at night and colour in the daytime. All markings (figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11) should be subordinate to the main colour of the buoy; the varying backgrounds and atmospheric conditions render the question a complex one.

London Trinity House buoys are divided into five classes, their use depending on whether the spot to be marked is in the open sea or otherwise exposed position, or in a sheltered harbour, or according to the depth of water and weight of moorings, or the importance of the danger. Buoys are moored with specially tested cables; the eye at the base of the buoy is of wrought iron to prevent it becoming “reedy” and the cable is secured to blocks (see Anchor) or mushroom anchors according to the nature of the ground. London Trinity House buoys are built of steel, with bulkheads to lessen the risk of their sinking by collision, and, with the exception of bell buoys, do not contain water ballast. In 1878 gas buoys, with fixed and occulting lights of 10-candle power, were introduced. In 1896 Mr T. Matthews, engineer-in-chief in the London Trinity Corporation, developed the present design (fig. 12). It is of steel, the lower plates being 58 in. and the upper 716 in. in thickness, thus adding to the stability. The buoy holds 380 cub. ft. of gas, and exhibits an occulting light for 2533 hours. This light is placed 10 ft. above the sea, and, with an intensity of 50 candles, is visible 8 m. It occults every ten seconds, and there is seven seconds’ visibility, with three seconds’ obscuration. The occultations are actuated by a double valve arrangement. In the body of the apparatus there is a gas chamber having sufficient capacity, in the case of an occulting light, for maintaining the flame in action for seven seconds, and by means of a by-pass a jet remains alight in the centre of the burner. During the period of three seconds’ darkness the gas chamber is re-charged, and at the end of that period is again opened to the main burner by a tripping arrangement of the valve, and remains in action seven seconds. The gas chamber of the buoy, charged to five atmospheres, is replenished from a steamer fitted with a pump and transport receivers carrying indicating valves, the receivers being charged to ten atmospheres. Practically no inconvenience has resulted from saline or other deposits, the glazing (glass) of the lantern being thoroughly cleaned when re-charging the buoy. Acetylene, generated from calcium carbide inside the buoy, is also used. Electric light is exhibited from some buoys in the United States. In England an automatic electric buoy has been suggested, worked by the motion of the waves, which cause a stream of water to act on a turbine connected with a dynamo generating electricity. Boat-shaped buoys are also used (river Humber) for carrying a light and bell. The Courtenay whistling buoy (fig. 13) is actuated by the undulating movement of the waves. A hollow cylinder extends from the lower part of the buoy to still water below the movement of the waves, ensuring that the water inside keeps at mean level, whilst the buoy follows the movements of the waves. By a special apparatus the compressed air is forced through the whistle at the top of the buoy, and the air is replenished by two tubes at the upper part of the buoy. It is fitted with a rudder and secured in the usual manner. Automatic buoys cannot be relied on in calm days with a smooth sea. The nun buoy (fig. 14) for indicating the position of an anchor after letting go, is secured to the crown of the anchor by a buoy rope. It is usually made of galvanized iron, and consists of two cones joined together at the base. It is painted red for the port anchor and green for the starboard.

|

|

|

| Fig. 12. | Fig. 13. | Fig. 14. |

Mooring buoys (fig. 6) for battleships are built of steel in four watertight compartments, and have sufficient buoyancy to keep afloat should a compartment be pierced; they are 13 ft. long with a diameter of 612 ft. The mooring cable (bridle) passes through a watertight 16-in. trunk pipe, built vertically in the centre of the buoy, and is secured to a “rocking shackle” on the upper surface of the buoy. Large mooring buoys are usually protected by horizontal wooden battens and are fitted with life chains. (J. W. D.)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 In carrying out the above system the Northern Lights Commissioners have adopted a red colour for conical or starboard-hand buoys, and black colour for can or port-hand buoys, and this system is applicable to the whole of Scotland.

- ↑ Useful where floating ice is encountered.

- ↑ St George and St Andrew crosses are principally employed to surmount shore beacons.