1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Castle

CASTLE (Lat. castellum, a fort, diminutive of castra, a camp; Fr. château and châtel), a small self-contained fortress, usually of the middle ages, though the term is sometimes used of prehistoric earthworks (e.g. Hollingbury Castle, Maiden Castle), and sometimes of citadels (e.g. the castles of Badajoz and Burgos) and small detached forts d’arrêt in modern times. It is also often applied to the principal mansion of a prince or nobleman, and in France (as château) to any country seat, this use being a relic of the feudal age. Under its twofold aspect of a fortress and a residence, the medieval castle is inseparably connected with the subjects of fortification (see Fortification and Siegecraft) and architecture (q.v.). An account of Roman and pre-Roman castella in Britain will be found under Britain.

The word “castle” (castel) was introduced into English shortly before the Norman Conquest to denote a type of fortress, then new to the country, brought in by the Norman knights whom Edward the Confessor had sent for to defend Herefordshire against the inroads of the Welsh. Richard’s castle, of which the earthworks remain and which has given its name to a parish, was erected at this period on the border of Herefordshire and Shropshire by Richard Fitz Scrob. The essential feature of this type was a circular mound of earth surrounded by a dry ditch and flattened at the top. Around the crest of

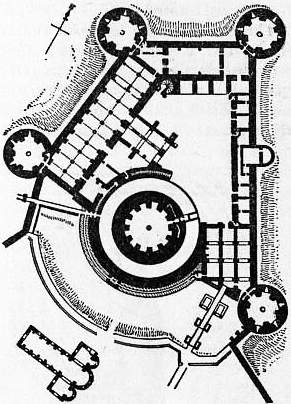

From Clark’s Medieval Military Architecture, by permission of Bernard Quaritch

Fig. 1.—Plan of Laughton en-le-Morthen.

its summit was placed a timber palisade. This moated mound was styled in French motte (latinized mota), a word still common in French place-names. It is clearly depicted at the time of the Conquest in the Bayeux tapestry, and was then familiar on the mainland of western Europe. A description of this earlier castle is given in the life of John, bishop of Terouanne (Acta Sanctorum, quoted by G. T. Clark, Medieval Mil. Architecture):—“The rich and the noble of that region being much given to feuds and bloodshed, fortify themselves . . . and by these strongholds subdue their equals and oppress their inferiors. They heap up a mound as high as they are able, and dig round it as broad a ditch as they can. . . . Round the summit of the mound they construct a palisade of timber to act as a wall. . . . Inside the palisade they erect a house, or rather a citadel, which looks

down on the whole neighbourhood.” St John, bishop of Terouanne, died in 1130, and this castle of Merchem, built by “a lord of the town many years before” may be taken as typical of the practice of the 11th century. But in addition to the mound, the citadel of the fortress, there was usually appended to it a bailey or basecourt (and sometimes two) of semilunar or horseshoe shape, so that the mound stood à cheval on the line of the enceinte. The rapidity and ease with which it was possible to construct castles of this type made them characteristic of the Conquest period in England and of the Anglo-Norman settlements in Wales, Ireland and the Scottish lowlands. In later days a stone wall replaced the timber palisade and produced what is known as the shell-keep, the type met with in the extant castles of Berkeley, Alnwick and Windsor.

But the Normans introduced also two other types of castle. The one was adopted where they found a natural rock stronghold which only needed adaptation, as at Clifford, Ludlow, the Peak and Exeter, to produce a citadel; the other was a type wholly distinct, the high rectangular tower of masonry, of which the Tower of London is the best-known example, though that of Colchester was probably constructed in the 11th century also. But the latter type belongs rather to the more settled conditions of the 12th century when haste was not a necessity, and in the first half of which the fine extant keeps of Hedingham and Rochester were erected. These towers were originally surrounded by palisades, usually on earthen ramparts, which were replaced later by stone walls. The whole fortress thus formed was styled a castle, but sometimes more precisely “tower and castle,” the former being the citadel, and the latter the walled enclosure, which preserved more strictly the meaning of the Roman castellum.

Reliance was placed by the engineers of that time simply and solely on the inherent strength of the structure, the walls of which defied the battering-ram, and could only be undermined at the cost of much time and labour, while the narrow apertures were constructed to exclude arrows or flaming brands.

At this stage the crusades, and the consequent opportunities afforded to western engineers of studying the solid fortresses of the Byzantine empire, revolutionized the art of castle-building, which henceforward follows recognized principles. Many castles were built in the Holy Land by the crusaders of the 12th century, and it has been shown (Oman, Art of War: the Middle Ages, p. 529) that the designers realized, first, that a second line of defences should be built within the main enceinte, and a third line or keep inside the second line; and secondly, that a wall must be flanked by projecting towers.

Fig. 2.—Vertical section of rectangular Norman Keep (Tower of London)

From the Byzantine engineers, through the crusaders, we derive, therefore, the cardinal principle of the mutual defence of all the parts of a fortress. The donjon of western Europe was regarded as the fortress, the outer walls as accessory defences; in the East each envelope was a fortress in itself, and the keep became merely the last refuge of the garrison, used only when all else had been captured. Indeed the keep, in several crusader castles, is no more than a tower, larger than the rest, built into the enceinte and serving with the rest for its flanking defence, while the fortress was made strongest on the most exposed front. The idea of the flanking towers (which were of a type very different from the slight projections of the shell-keep and rectangular tower) soon penetrated to Europe, and Alnwick Castle (1140–1150) shows the influence of the new system.

|

|

|

But the finest of all castles of the middle ages was Richard Cœur de Lion’s fortress of Château Gaillard (1197) on the Seine near Les Andelys. Here the innermost ward was protected by an elaborate system of strong appended defences, which included a strong tête-de-pont covering the Seine bridge (see Clark, i. 384, and Oman, p. 533). The castle stood upon high ground and consisted of three distinct enceintes or wards besides the keep, which was in this case merely a strong tower forming part of the innermost ward. The donjon was rarely defended à outrance, and it gradually sank in importance as the outer “wards” grew stronger. Round instead of rectangular towers were now becoming usual, the finest examples of their employment as keeps being at Conisborough in England and at Coucy in France. Against the relatively feeble siege artillery of the 13th century a well-built fortress was almost proof, but the mines and the battering ram of the attack were more formidable, and it was realized that corners in the stonework of the fortress were more vulnerable than a uniform curved surface. Château Gaillard fell to Philip Augustus in 1204 after a strenuous defence, and the success of the assailants was largely due to the wise and skilful employment of mines. An angle of the noble keep of Rochester was undermined and brought down by John in 1215.

|

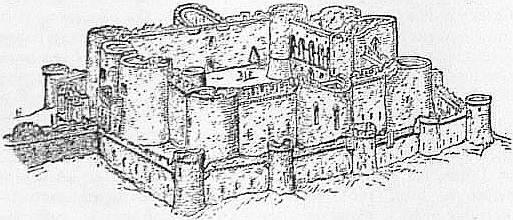

Fig. 5.—Krak-des-Chevaliers: View. |

A. High Angle Tower B.B. Smaller Side Towers C.C. D.D. Corner Towers E. Outer Enceinte, or Lower Court F. The Well G.H. Buildings in the Lower Court I. The Moat |

K. Entrance Gate L. The Counterscarp M. The Keep N. The Escarpment O. Postern Tower P. Postern Gate R.R. Parapet Walls |

S. Gate from the Escarpment T.T. Flanking Towers V. Outer Tower X. Connecting Wall Y. The Stockade in the River Z.Z. The Great Ditches |

Fig. 6.—Château Gaillard. | ||

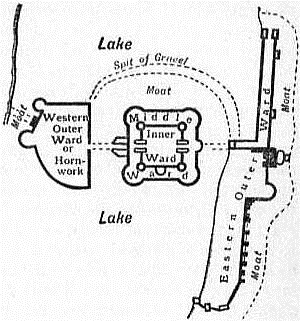

The next development was the extension of the principle of successive lines of defence to form what is called the “concentric” castle, in which each ward was placed wholly within another which enveloped it; places thus built on a flat side (e.g. Caerphilly Castle) became for the first time more formidable than strongholds perched upon rocks and hills such as Château Gaillard, where the more exposed parts indeed possessed many successive lines of defence, but at other points, for want of room, it was impossible to build more than one or, at most, two walls. In these cases, the fall of the inner ward by surprise, escalade, vive force, or even by regular siege (as was sometimes feasible), entailed the fall of the whole castle.

The adoption of the concentric system precluded any such mischance, and thus, even though siege-engines improved during the 13th and 14th centuries, the defence, by the massive strength of the concentric castle in some cases, by natural inaccessibility of position in others, maintained itself superior to the attack during the latter middle ages. Its final fall was due to the introduction of gunpowder as a propellant. “In the 14th century the change begins, in the 15th it is fully developed, in the 16th the feudal fastness has become an anachronism.”

The general adoption of cannon placed in the hands of the central power a force which ruined the baronial fortifications in a few days of firing. The possessors of cannon were usually private individuals of the middle classes, from whom the prince hired the matériel and the technical workmen. A typical case will be found in the history of Brandenburg and Prussia (Carlyle, Frederick the Great, bk. iii. ch. i.), the impregnable castle of Friesack, held by an intractable feudal noble, Dietrich von Quitzow, being reduced in two days by the elector Frederick. I. with “Heavy Peg” (Faule Grete) and other guns hired and borrowed (February 1414). The beginnings of orderly government in Brandenburg thus depended upon the guns, and the taking of Friesack is, in Carlyle’s phrase, “a fact memorable to every Prussian man.” In England, the earl of Warwick in 1464 reduced the strong fortress of Bamborough in a week, and in Germany, Franz von Sinkingen’s stronghold of Landstuhl, formerly impregnable on its heights, was ruined in one day by the artillery of Philip of Hesse (1523). Very heavy artillery was used for such work, of course, and against lighter natures, some castles and even fortified country-houses or castellated mansions managed to make a stout stand even as late as the Great Rebellion in England.

From Clark’s Med. Mil. Arch.

Fig. 9.—Beaumaris Castle: Plan.

The castle thus ceases to be the fortress of small and ill-governing local magnates, and its later history is merged in that of modern fortification. But an interesting transitional type between the medieval stronghold and the modern fortress is found in the coast castles erected by Henry VIII., especially those at Deal, Sandown and Walmer (c. 1540), which played some part in the events of the 17th century, and of which Walmer Castle is still the official residence of the lord warden of the Cinque Ports. Viollet-le-Duc, in his Annals of a Fortress (English trans.), gives a full and interesting account of the repeated renovations of the fortress on his imaginary site in the valley of the Doubs, the construction by Charles the Bold of artillery towers at the angles of the castle, the protection of the masonry by earthen outworks, boulevards and demi-boulevards, and, in the 17th century, the final service of the medieval walls and towers as a pure enceinte de sûreté. Here and there we find old castles serving as forts d’arrêt or block-houses in mountain passes and defiles, and in some few cases, as at Dover, they formed the nucleus of purely military places of arms, but normally the castle falls into ruins, becomes a peaceful mansion, or is merged in the fortifications of the town which has grown up around it. In the Annals of a Fortress the site of the feudal castle is occupied by the citadel of the walled town, for once again, with the development of the middle class and of commerce and industry, the art of the engineer came to be displayed chiefly in the fortification of cities. The baronial “castle” assumes pari passu the form of a mansion, retaining indeed for long some capacity for defence, but in the end losing all military characteristics save a few which survived as ornaments. Examples of such castellated mansions are seen in Wingfield Manor, Derbyshire, and Hurstmonceaux, Sussex, erected in the 15th century, and nearly all older castles which survived were continually improved and altered to serve as residences. (C. F. A.)

Influence of Castles in English History.—Such strongholds as existed in England at the time of the Norman Conquest seem to have offered but little resistance to William the Norman, who, in order effectually to guard against invasions from without as well as to awe his newly-acquired subjects, immediately began to erect castles all over the kingdom, and likewise to repair and augment the old ones. Besides, as he had parcelled out the lands of the English amongst his followers, they, to protect themselves from the resentment of the despoiled natives, built strongholds and castles on their estates, and these were multiplied so rapidly during the troubled reign of King Stephen that the “adulterine” (i.e. unauthorized) castles are said by one writer to have amounted to 1115.

In the first instance, when the interest of the king and of his barons was identical, the former had only retained in his hands the castles in the chief towns of the shires, which were entrusted to his sheriffs or constables. But the great feudal revolts under the Conqueror and his sons showed how formidable an obstacle to the rule of the king was the existence of such fortresses in private hands, while the people hated them from the first for the oppressions connected with their erection and maintenance. It was, therefore, the settled policy of the crown to strengthen the royal castles and increase their number, while jealously keeping in check those of the barons. But in the struggle between Stephen and the empress Maud for the crown, which became largely a war of sieges, the royal power was relaxed and there was an outburst of castle-building, without permission, by the barons. These in many cases acted as petty sovereigns, and such was their tyranny that the native chronicler describes the castles as “filled with devils and evil men.” These excesses paved the way for the pacification at the close of the reign, when it was provided that all unauthorized castles constructed during its course should be destroyed. Henry II., in spite of his power, was warned by the great revolt against him that he must still rely on castles, and the massive keeps of Newcastle and of Dover date from this period.

Under his sons the importance of the chief castles was recognized as so great that the struggle for their control was in the forefront of every contest. When Richard made vast grants at his accession to his brother John, he was careful to reserve the possession of certain castles, and when John rose against the king’s minister, Longchamp, in 1191, the custody of castles was the chief point of dispute throughout their negotiations, and Lincoln was besieged on the king’s behalf, as were Tickhill, Windsor and Marlborough subsequently, while the siege of Nottingham had to be completed by Richard himself on his arrival. To John, in turn, as king, the fall of Château Gaillard meant the loss of Rouen and of Normandy with it, and when he endeavoured to repudiate the newly-granted Great Charter, his first step was to prepare the royal castles against attack and make them his centres of resistance. The barons, who had begun their revolt by besieging that of Northampton, now assailed that of Oxford as well and seized that of Rochester. The king recovered Rochester after a severe struggle and captured Tonbridge, but thenceforth there was a war of sieges between John with his mercenaries and Louis of France with his Frenchmen and the barons, which was specially notable for the great defence of Dover Castle by Hubert de Burgh against Louis. On the final triumph of the royal cause, after John’s death, at the battle of Lincoln, the general pacification was accompanied by a fresh issue of the Great Charter in the autumn of 1217, in which the precedent of Stephen’s reign was followed and a special clause inserted that all “adulterine” castles, namely those which had been constructed or rebuilt since the breaking out of war between John and the barons, should be immediately destroyed. And special stress was laid on this in the writs addressed to the sheriffs.

In 1223 Hubert de Burgh, as regent, demanded the surrender to the crown of all royal castles not in official custody, and though he succeeded in this, Falkes de Breauté, John’s mercenary, burst into revolt next year, and it cost a great national effort and a siege of nearly two months to reduce Bedford Castle, which he had held. Towards the close of Henry’s reign castles again asserted, in the Baron’s War, their importance. The Provisions of Oxford included a list of the chief royal castles and of their appointed castellans with the oath that they were to take; but the alien favourites refused to make way for them till they were forcibly ejected. When war broke out it was Rochester Castle that successfully held Simon de Montfort at bay in 1264, and in Pevensey Castle that the fugitives from the rout of Lewes were able to defy his power. Finally, after his fall at Evesham, it was in Kenilworth Castle that the remnant of his followers made their last stand, holding out nearly five months against all the forces of the crown, till their provisions failed them at the close of 1266.

Thus for two centuries after the Norman Conquest castles had proved of primary consequence in English political struggles, revolts and warfare. And, although, when the country was again torn by civil strife, their military importance was of small account, the crown’s historic jealousy of private fortification was still seen in the need to obtain the king’s licence to “crenellate” (i.e. embattle) the country mansion.

Bibliography.—G. T. Clark, Medieval Military Architecture in England (2 vols.), includes a few French castles and is the standard work on the subject, but inaccurate and superseded on some points by recent research; Professor Oman’s Art of War in the Middle Ages is a wide survey of the subject, but follows Clark in some of his errors; Mackenzie, The Castles of England (1897), valuable for illustrations; Deville, Histoire du Château-Gaillard (1829) and Château d’Argues (1839); Viollet-le-Duc’s Essay on the Military Architecture of the Middle Ages was translated by M. Macdermott in 1860. More recent studies will be found in J. H. Round’s Geoffrey de Mandeville (1891); “English Castles” (Quarterly Review, July 1894); and “Castles of the Conquest” (Archeologia, lviii., 1902); St John Hope’s “English Castles of the 10th and 11th Centuries” (Archaeol. Journal, lx., 1902); Mrs Armitage’s “Early Norman Castles of England” (Eng. Hist. Review, xix. 1904), and her papers in Scot. Soc. Ant. Proc. xxxiv., and The Antiquary, July, August, 1906; G. Neilson’s “The Motes in Norman Scotland” (Scottish Review, lxiv., 1898); G. H. Orpen, “Motes and Norman Castles in Ireland” (Eng. Hist. Review, xxi., xxii., 1906–1907). (J. H. R.)