A Book of Dartmoor/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII.

HOLNE

AT Holne the old church house, now an inn, affords very comfortable quarters, and from it many interesting excursions may be made.

Holne church has preserved its old screen and pulpit, the former rich with paintings of saints. Both were probably erected by Oldam, Bishop of Exeter, 1504-19. In the churchyard is the following doggerel inscription:—

"Here lies poor old Ned, on his last mattrass bed.

During life he was honest and free;

He knew well the chase, but has now run his race,

And his name it was Colling, d'ye see.

He died December 28th, 1780, aged 77."

From the vicarage garden a noble view of the windings of the Dart through Holne Chase is to be obtained—permission asked and given.

To see Holne Chase, it should be ascended as far as New Bridge, and thence descended through the Buckland Drives. Permission is given on fixed days.

In Holne Wood, where the river makes a loop, is an early camp, with indications of hut circles in it, but thrown out of shape by the trees growing in the area. Near the entrance charcoal-burners have formed their hole in which to burn the timber. A finer and better preserved camp is Hembury.

In the Chase, on the Buckland side under Awsewell Rock, are the remains of furnaces and great heaps of slag. The point is where there is a junction of the granite and the sedimentary rocks. Above the wooded flank of the hill, the rocks are pierced and honeycombed by miners following veins of ore, probably copper. The workings are very primitive, and deserve inspection. The little village of Buckland should not be neglected. It is marvellously picturesque, but the houses do not appear to be healthy, being buried in foliage. The church has not been restored. It possesses an old screen with curious paintings, some impossible to interpret; and it is in the old bepewed, neglected condition familiar now only to those whose years number something about sixty or seventy. Buckland-in-the-Moor is the full name of this parish, but it is no longer in the moor. Colonel Bastard, ancestor of the present owner, planted all the heathery land and hillsides with trees, and received therefor the thanks of Parliament as one who by so doing had deserved well of his country.

If Holne Chase be beautiful, so is the Dart above New Bridge. A more interesting drive can hardly be taken than one branching off from the main road before reaching Pound's Gate and following a grassy track called "Dr. Blackall's Drive," that sweeps round the heights above the Dart and rejoins the road between Mel Tor and Sharpie Tor.

But to see the Dart valley in perfection the river should be followed up on foot from New Bridge to that of Dartmeet, and thence up to Post Bridge.

The descent to Dartmeet by the road is one of over five hundred feet. Halfway is the Coffin-stone, on which five crosses are cut, and which is split in half—the story goes, by lightning. On this it is customary to rest a dead man on his way from the moor beyond Dartmeet to his final resting-place at Widdecombe. When the coffin is laid on this stone, custom exacts the production of the whisky bottle, and a libation all round to the manes of the deceased.

One day a man of very evil life, a terror to his neighbours, was being carried to his burial, and his corpse was laid on the stone whilst the bearers regaled themselves. All at once, out of a passing cloud shot a flash, and tore the coffin and the dead man to pieces, consuming them to cinders, and splitting the stone. Do you doubt the tale? See the stone cleft by the flash.

Among the many hundreds who annually visit Dartmeet, I do not suppose that more than one sees the real beauties to which this spot opens the way. Actually, Dartmeet Bridge is situated at the least interesting and least picturesque point on the river.

To know the Dart and see its glories, a visitor must desert the bridge and ascend the river. I will indicate to him two walks, each of remarkable beauty and each an easy one.

The first is this: Ascend the Dart on the left. This can be done by passing through a gate above Dartmeet Cottage, and descending to the river, where remain a few of the venerable oaks that once abounded at Brimpts, but were wantonly cut down at the beginning of this century. Ascend by a fisherman's path through the plantation to where the wood ends, and the hills falling back reveal a pleasant meadow, with, rising out of it by the river, a holt or pile of rocks overgrown with oaks. The view from this is beautiful. Proceeding half a mile a ruined cottage is reached, where the stately Yar Tor may be seen to advantage. This ruin is called Dolly's Cot.

Dolly, who has given her name to this ruin, was a somewhat remarkable woman. She lived with her brother, orphans, by Princetown when Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt settled at Tor Royal. She was a remarkably handsome girl, and she seems to have caught the eye of this gentleman, who located her and her brother in the lodge, and then, as the brother kept a sharp look-out on his sister, he got rid of him by obtaining for him an appointment in the House of Lords, where he looked after the lighting, and had as his perquisite the ends of the wax tapers. As fresh candles were provided every day, and the sessions were at times short, the perquisites were worth a good deal.

However, if the brother were away Dolly had

The Cleft Rock above Hotlne Chase

relish the manner in which Sir Thomas, Warden of the Stannaries, hovered about Miss Dolly.

But a climax was reached when the Prince Regent arrived at Tor Royal to visit his forest of Dartmoor. The Prince's eye speedily singled Dolly out, and the blue coat and brass buttons, white ducks tightly strapped, and the curled-brimmed hat were to be seen on the way to Dolly's cottage a little too frequently to please Tom Trebble. So to cut his anxieties short he whisked Dolly on to the pillion of his moor cob and rode off with her to Lydford, where they were married. Then he carried her away to this cottage—now a ruin—on the Dart, to which led no road, hardly a path even, and where she was likely to be out of the way of both the Prince and his humble servant, Sir Thomas.

In this solitary cottage Tom and Dolly lived for many years. She survived her husband, and gained her livelihood by working at the tin-mine of Hexworthy, where one of the shafts recently sunk was named after her.

The candle-snuffer realised—so it was said—a good fortune out of the wax taper-ends, and never returned to Dartmoor.

Dolly lived to an advanced age, and even as an old woman was remarkably handsome and of a distinguished appearance.

It is now difficult to collect authentic information concerning her, as only very old people remember Dolly. She was buried at Widdecombe, and aged moor folk still speak of her funeral, at which all the women mourners wore white skirts, i.e. their white petticoats without the coloured skirts of their gowns, and white kerchiefs pinned as crossovers to cover their shoulders.

The distance is between six and seven miles. Dolly was borne to her grave by the tin-miners, and followed not only by the mine-workers, but by all the women of the moorside, and all in their white petticoats; and as they went they sang psalms.

From Dolly's Cot the hill can be ascended to 'The Seven Sisters," seven conspicuous old Scotch pines, whereof one has lost its head. Thence a road is reached that takes a visitor back to Dartmeet by Brimpts.

The other walk, even finer, is this: Ascend the hill on the Ashburton road till a road breaks away to the left to Sherrill. Follow this, when on the col a kistvaen, inclosed in a circle, is reached. North of this is a much-ruined set of stone rows, three parallel lines running 660 feet, but so plundered that only 158 stones remain. The road descends to a pleasant little settlement, Sherrill, or Sher-well, consisting of a farm and some cottages. The Sher-well bursts out in one strong spring beside the road, and becomes a good stream almost directly.

The situation is warm and sheltered, and the ground is cultivated. The road descends to the Wallabrook, which it crosses, to Babeney. Thence a track leads down the Wallabrook to its junction

with the Dart, where is disclosed what I hold to be one

Var Tor

are so situated as to show themselves to such advantage. On the right, a spur well clothed in dark fir plantations comes down from Brimpts; and on the left is a clitter of bold granite rocks. The time to visit this is certainly the evening, when Yar Tor is bathed in a golden glory, and the woods are steeped in royal purple.

Thence a path, or track rather, leads down the Dart on the east side, past Badgers' Holt to the bridge.

And perhaps on the way the Graphis scripta may be found, but it is chiefly to be discovered on old hollies, a mysterious writing, characters scrawled by delicate hands, and understandable only by the pixies, who are credited with thus writing their messages to one another. Actually this is a lichen, that strangely affects a script.

It was at Badgers' Holt that old Dan Leaman lived, on whom a trick was played which I have already related in my Book of the West.

What a solitary life must have been led by the occupants of the scattered farms and cottages at Babeney, Sherrill, Dury, and the like, in former times! And yet those who occupied them got to love the isolation. A woman at Sherrill, who had been in service and had married a moorman, said to me, "I wouldn't live here if I could help it; but, Lor' bless y', my old man, there's no gettin' he away from atop o' Widdecombe chimney"—that is to say, the level of the church tower. The reach of its bells formed the world—the only world in which he cared to live. In a cottage near Sherrill lived an old woman absolutely alone, who for sixty years never once allowed her fire to go out.

If it be desired to open out Dartmoor, a road should be carried up the Dart from New Bridge to Dartmeet, and thence, still following the river, to Post Bridge. The owners of the banks of the Dart below New Bridge to Holne Bridge—in fact, of Holne Chase—could then hardly refuse to allow it to be carried through their land to Holne Bridge, and then a drive would be created passing through scenery unsurpassed in England. Another ought to be engineered up the Webburn from its meet with the Dart, past Lizwell to Widdecombe; then that solitary village would be at once accessible, and brought into the world.

Below Dartmeet Bridge, if the river be followed on the right through a wood, the Pixy Holt is reached, a cave in which the little good folk are supposed to dwell. It is the correct thing to leave a pin or some other trifle in acknowledgment when visiting their habitation.

Where the Okebrook drops into the West Dart is an old blowing-house, with moulds for the tin, ruined, and with a stout oak growing up in the midst There are also mortar-stones in the ruin. Above Huccaby Bridge are the remains of a fine circle of standing stones that has been sadly mutilated. Another, far more perfect, is at Sherberton.

Near the bridge is Jolly Lane Cot, the house of Sally Satterleigh, that was built and occupied in one day. Her father was desirous of marrying a wife and bringing her to a home; but he had no home to which to introduce her, and the farmers round not only would afford no help, but proved obstructive. One day when it was Holne Revel, and the farmers had gone thither, the labouring people assembled in swarms, set to work and built up the cottage, and before the farmers returned, lively with drink, from the revel, the man was in the cottage and had lighted a fire on the hearth, and this constituted a freeholding from which no man might dispossess him. This man was a notable singer, and his old daughter, now a grandmother, remembered some of his songs. One wild and stormy day, Mr. Bussell, of Brazen Nose College, now Dr. Bussell and tutor of his college, drove over with me from Princetown to get her songs from her.

But old Sally could not sit down and sing. We found that the sole way in which we could extract the ballads from her was by following her about as she did her usual work. Accordingly we went after her when she fed the pigs, or got sticks from the firewood rick, or filled a pail from the spring, pencil and notebook in hand, dotting down words and melody. Finally she did sit to peel some potatoes, when Mr. Bussell with a MS. music-book in hand, seated himself on the copper. This position he maintained as she sang the ballad of "Lord Thomas and the Fair Eleanor," till her daughter applied fire under the cauldron, and Mr. Bussell was forced to skip from his perch.

Holne forms the extreme eastern end of a long ridge that terminates to the west in Down Tor. This hog's back stands over 1,500 feet above the sea, and is the watershed. From it stream the Avon, the Erme, the Yealm, and the Plym in a southerly direction, and north of it are the West Dart and the Swincombe river. It is a rounded back of moor, without granite tors, thickly sown with bogs. But there is a track, the Sandy Way, that threads these morasses from Holne, and leads to Childe's Tomb, a kistvaen, with a cross near it.

The story is well known.

A certain Childe, a hunter, lost his way in winter in this wilderness. Snow fell thick and his horse could go no further.

"In darkness blind, he could not find

Where he escape might gain,

Long time he tried, no track espied,

His labours all in vain.

"His knife he drew, his horse he slew

As on the ground it lay;

He cut full deep, therein to creep,

And tarry till the day.

"The winds did blow, fast fell the snow,

And darker grew the night,

Then well he wot he hope might not

Again to see the light.

"So with his finger dipp'd in blood,

He scrabbled on the stones—

'This is my will, God it fulfil,

And buried be my bones.

" ' Whoe'er it be that findeth me,

And brings me to a grave;

The lands that now to me belong

In Plymstock he shall have.' "

The kistvaen is, of course, not Childe's grave, for it is prehistoric, and Childe was not buried there. But the cross may have been set up to mark the spot where he was found.

Childe's Cross was quite perfect, standing on a three-stepped pedestal, till in or about 1812, when it was nearly destroyed by the workmen of a Mr. Windeatt, who was building a farmhouse near by. The stones that composed it have, however, been for the most part recovered, and the cross has been restored as well as might be under the circumstances.

The Sandy Way was doubtless a very ancient track across the moor from east to west, as it is marked by crosses, as may be judged by the Ordnance map. 1, Horne's Cross; 2 and 3, crosses on Down Ridge; 4 and 5, crosses on Terhill; 6 and 7, crosses near Fox Tor, in the Newtake; 8,Childe's Cross; 9, Seward's or Nun's Cross; 10, cross on Walkhampton Common.

Swincombe, formerly Swan-combe, runs to the north of the ridge, and has the sources of its river in the Fox Tor mires and near Childe's Tomb.

It runs north-east, and then abruptly passes north to decant into the West Dart.

Near this is Gobbetts Mine, a very interesting spot, for here are samples of the modern deep mining shaft, the shallow workings, and the deep, open cuttings of the earlier times, and the stream works of the "old men." Thus we have on one spot a compendium of the history of mining for tin. Among the relics lying about are the remains of an old

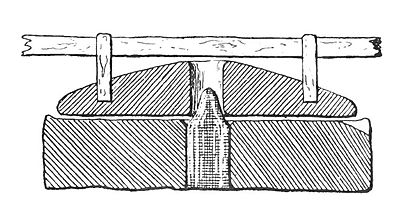

Crazing-Mill Stone, Upper Gobbetts

crazing-mill, consisting of the upper and the nether stones. The nether stone is 3 feet 10 inches in diameter, and 10 inches thick. In the periphery is a groove forming a lip, that served readily to discharge the ground material.

The upper stone has a roughly convex back, and an eye as well as four holes drilled in it. Into these holes posts were fitted, which carried two bars, so that the stone was made to revolve by horse or man power, like the arrangement of a capstan.

The hole or eye of the nether stone was for the purpose of receiving a conical plug, the apex of which penetrated partly into the eye of the upper stone, and served the double purpose of keeping the runner stone in position and of distributing the feed equally on the grinding-surfaces. To further assist

Method of Using the Mill-stone. Section.

this are four curved master-turrows or grooves, radiating from the eye of the grinding-surface of the upper stone. The mill, worked by men or by horses, was of slow speed, and water was introduced to assist the propulsion of the ground material towards the grooved lip in the periphery of the stone. This and the feed were, of course, introduced through the circular hole in the top stone.

On the site of what was evidently the blowing-house is a mould-stone, about 4 feet by 3. The mould is 15 inches long by 11 inches wide at one end, and 10 inches at the other, and 4 to 5 inches deep. There are also cavities for sample ingots.

Other stones lie about with hollows worked in them, that seem to have been mortar-stones, used for pounding up the ore, at a period earlier than that at which the crazing-mill was introduced.

Further up the Swincombe, on the left, a little stream descends that has had its bed turned over and over. This is Deep Swincombe, and here are the remains of the earliest known smelting-house yet noticed on Dartmoor. It has been fully described in a previous chapter. On all sides we discover traces of those who in ancient times came to Dartmoor and toiled after metal. We go in swarms there now—to spend our metal and idle and gain health. So the old order changeth, and with it men's moods and manners.

To return to Holne. In the parsonage Charles Kingsley was born, but the house has since been to a large extent rebuilt. On a fly-sheet of the Book of Burial Registers is the entry, "The Vicarage House, being very dilapidated, was taken down and rebuilt by the Vicar (the Rev. John D. Parham) in the year 1832." It was in that "very dilapidated" house that Charles Kingsley was born.

A curious custom existed at Holne, now given up. There is, near the village, a "Ploy (play) Field" in which stood formerly a rude granite stone six or seven feet high.

On May morning, before daybreak, the young men of the village were wont to assemble there and then proceed to the moor, where they selected a ram lamb, and, after running it down, brought it in triumph to the Ploy Field, fastened it to the granite post, cut its throat, and then roasted it whole—skin, wool, etc. At midday a struggle took place, at the risk of cut hands, for a slice, it being supposed to confer luck for the ensuing year on the fortunate devourer. As an act of gallantry the young men sometimes fought their way through the crowd to get a slice for the chosen amongst the young women, all of whom, in their best dresses, attended the Ram Feast, as it was called. Dancing, wrestling, and other games, assisted by copious libations of cider during the afternoon, prolonged the festivity till midnight. This is now entirely of the past, but a somewhat similar popular festival survives at King's Teignton, or did so till recently. There Whitsuntide is the season chosen. A lamb is drawn about the parish on Whitsun Monday in a cart covered with garlands of lilac, laburnum, and other flowers, when persons are requested to give something towards the animal and attendant expenses. On Tuesday morning it is killed and roasted whole in the middle of the village. The lamb is then sold in slices to the poor at a cheap rate. The story told to account for this festival is that the village once suffered from a dearth of water, when the inhabitants were advised to pray for water; whereupon a fountain burst forth in a meadow about a third of a mile above the river, in an estate now called Rydon, a supply sufficient to meet the necessities of the villagers. A lamb, it is said, has ever since been sacrificed as a return offering at Whitsuntide in the manner above mentioned.

The said water appears like a large pond, from which in rainy weather may be seen jets springing up some inches above the surface in many parts.

I know the case of a farmer on the edge of Dartmoor, whose cattle were afflicted with some disorder in 1879; he thereupon conveyed a sheep to the ridge above his house, sacrificed and burnt it there, as an offering to the Pysgies. The cattle at once began to recover, and did well after, nor were there any fresh cases of sickness amongst them. Since then I have been told of other and very similar cases.