A Book of the West/Volume 1/20

CHAPTER XX.

PLYMOUTH

WHEN a sailor heard the song sung, to which this is the refrain:—

"O dear Plymouth town ! and blue Plymouth Sound,

O where is your equal on earth to be found?"

he said, "Them's my opinions, to the turn of a hair."

About Plymouth town I am not so confident, but as to the Sound it is not easily surpassed. The Bay of Naples has Vesuvius, and above an Italian sky, but lacks the wealth of verdure of Mount Edgcumbe, and has none of those wondrous inlets that make of Plymouth Sound a figure of a watery hand displayed, and of the Three Towns a problem in topography which it requires long experience to solve.

The name of the place is a misnomer.

Plym is not the name of the river which has its mouth where the town squats. Plym is the contraction for Pen-lynn, the head of the lake, and was given originally to Plympton, where are the remains of a castle, and where are still to be seen the iron rings to which vessels were moored. But just as the Taw-ford (ridd) has contributed a name to the river Torridge, above the ford, so has Pen-lynn sent its name down the stream and given it to Plymouth. Pelynt in Cornwall is likewise a Pen-lynn.

What the original name of the river was is doubtful. Higher up, where it comes rioting down from the moor, above the Dewerstone is Cadover Bridge, not the bridge over the Cad, but Cadworthy Bridge. Perhaps the river was the Cad, so called from caed, contracted, shut within banks, very suitable to a river emerging from a ravine. A witty friend referring to "the brawling Cad," the epithet applied to it by the poet Carrington, said that it was not till the institution of chars-a-bancs and early-closing days in Plymouth that he ever saw "the brawling cad" upon Dartmoor; since then he has seen a great deal too much of the article.

Plymouth as a town is comparatively modern. When Domesday was compiled nothing was known of it, but there was a Sutton—South Town—near the pool, which eventually became the port of old Plymouth.

It first acquired some consequence when the Valletorts had a house near where is now the church of S. Andrew.

There was, however, a lis or enclosed residence of a chief, if we may accept the Domesday manor of Lisistone[1] as thence derived. And there have been early relics turned up occasionally. But no real consequence accrued to the place till the Valletorts set up house there in the reign of Henry I.

The old couplet, applied with variations to so many places in the kingdom, and locally running:

"Plympton was a borough town

When Plymouth was a vuzzy down,"

was true enough. Plympton at the time of the Conquest was head of the district, and there were then canons there in the monastery, which dates back at least to the reign of Edgar, probably to a much earlier period. The priors of Plympton got a grant of land in Sutton, which they held as lords of the manor till 1439. was not till the end of the thirteenth century that the name of Plymouth came to knowledge and the place began to acquire consequence. But it was not till the days of good Queen Bess that the place became one of prime importance.

"In the latter half of the sixteenth century," says Mr. Worth, "Devonshire was the foremost county in England, and Plymouth its foremost town. Elizabeth called the men of Devonshire her right hand, and so far carried her liking for matters Devonian, that one of the earliest passports of Raleigh to her favour was the fact that he talked the broadest dialect of the shire, and never abandoned it for the affected speech current at court."[2]

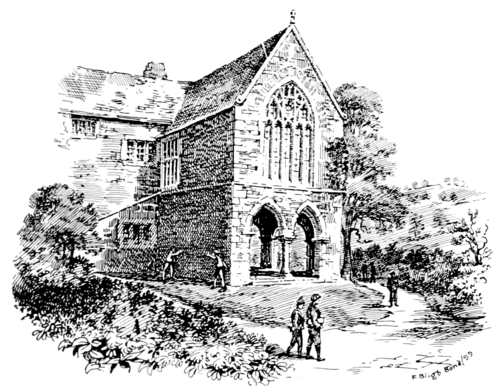

GRAMMAR SCHOOL

IN PLYMPTON

The importance of Plymouth as a starting-point for discovery, and as the cradle of our maritime power, must never be forgotten.

Old Carew says:—

"Here have the troops of adventurers made their rendezvous for attempting new discoveries or inhabitances, as Thomas Stukeleigh for Florida, Sir Humfrey Gilbert for Newfoundland, Sir Richard Grenville for Virginia, Sir Martin Frobisher and Master Davies for the North-West Passage, Sir Walter Raleigh for Guiana."

It is indeed no exaggeration to say that in the reign of Elizabeth Plymouth had become the foremost port in England.

"If any person desired to see her English worthies, Plymouth was the likeliest place to seek them. All were in some fashion associated with the old town. These were days when men were indifferent whether they fought upon land or water, when the fact that a man was a good general was considered the best of all reasons why he should be a good admiral likewise. 'Per mare per terram' was the motto of Elizabeth's true-born Englishmen, and familiar and dear to them was Plymouth, with its narrow streets, its dwarfish quays, its broad waters, and its glorious Hoe."

The roll of Plymouth's naval heroes begins with the Hawkins family, and one looks in vain in modern Plymouth for some statue to commemorate the most illustrious of her sons.

These Hawkinses were a remarkable race. "Gentlemen," as Prince says, "of worshipful extraction for several descents," they were made more worshipful by their deeds.

"For three generations in succession they were the master-spirits of Plymouth in its most illustrious days; its leading merchants, its bravest sailors, serving oft and well in the civic chair and the Commons House of Parliament. For three generations they were in the van of English seamanship, founders of England's commerce in South, West, and East, stout in fight, of quenchless spirit in adventure—a family of merchant statesmen and heroes to whom our country affords no parallel."[3]

The early voyages of Sir John Hawkins were to the Canary Isles. In 1562 he made his first expedition in search of negroes to sell in Hispaniola, so that he was not squeamish in the matter of the trade in human flesh. But in 1567 he made an expedition ever memorable, for his were the first English keels to furrow that hitherto unknown sea, the Bay of Mexico. He had with him a fleet of six ships, two of which were royal vessels, the rest were his own, and one of these, the Judith, was commanded by his kinsman, Francis Drake. Whilst in the port of S. Juan cle Ulloa Hawkins was treacherously assailed, and lost all the vessels, with the exception of two, of which one was the Judith. When his brother William heard of the disaster he begged Elizabeth to allow him to make reprisals on his own account; and on the return of John "it may fairly be said that Plymouth declared war against Spain. Hawkins and Drake thereafter never missed a chance of making good their losses. The treachery of San Juan de Ulloa was the moving cause of the series of harassments which culminated in the destruction of the Armada. For every English life then lost, for every pound of English treasure then taken, Spain paid a hundred and a thousand fold."

In the following year, at Rio de la Flacho, whilst getting in supplies, he was attacked by Michael de Castiliano with a thousand men. Hawkins had but two hundred under his command; however, he drove the Spaniards back, entered the town, and carried off the ensign, for which, on his return, he was granted an addition to his arms—on a canton, gold, an escalop between two palmers' staves, sable.

In 1573 Hawkins was chosen by the queen "as the fittest person in her dominions to manage her naval affairs," and for twenty-one years served as Controller of the Navy. It was through his wise provision, by his resolution, in spite of the niggard-liness wherewith Elizabeth doled out money, that "when the moment of trial came," says Froude, "he sent her ships to sea in such condition—hull, rigging, spars, and running rope—that they had no match in the world."

About the Armada presently.

In 1595 Hawkins and Drake were together sent to the West Indies in command of an expedition. But they could not agree. Hawkins wanted at once to sail for America, Drake to hover about the Canaries to intercept Spanish galleons. The disagreement greatly irritated old Sir John, unaccustomed to have his will opposed. Then he learned that one of his vessels, named the Francis, had been taken by the Spaniards. Grief at this, and annoyance caused by the double command, brought on a fever, and he died at sea, November 15th, 1595.

Old Prince says, in drawing a parallel between him and Drake, "In their deaths they were not divided, either in respect of the cause thereof, for they died both heart-broken; the one, for that being in joint commission with the other, his advice and counsel was neglected; the other, for the ill success with which his last voyage was attended. Alike they were also in their deaths; as to the place, for they both died on the sea; as to the time, they both expired in the same voyage, the one a little before the other, about the interspace of a few months; and lastly, as to their funerals, for they were both buried in the ocean, over which they had both so often rid in triumph."

The elder brother of Sir John, William, the patriarch of the port, was Mayor of Plymouth in the Armada year. William's son, Sir Richard Hawkins, sailed in 1593 from Plymouth with five vessels to the South Seas, and was taken by the Spaniards. From various causes the fleet was reduced to the single vessel the Dainty, which he himself commanded. Manned by seventy-five men

only, she was assailed by eight Spanish vessels with crews of 1300. Nevertheless, like Sir Richard Grenville, of the Revenge, he showed lusty fight, which was kept up for three days, and he did not surrender till he had himself been wounded six times, and then only when he had secured honourable terms, which the false scoundrels broke, by sending

SUTTON POOL

their prisoners to Spain, instead of allowing them, as was undertaken, to return to England.

He is one of those to whom the ballad is supposed to relate:—

"Would you hear of a Spanish lady,

How she wooed an English man?"

But it is also told of a member of the Popham family, by whom the lady's picture, and her chain and bracelets, mentioned in the ballad, were preserved.

Next to the Hawkins heroes we have Drake, a Plymothian by adoption, the son of a yeoman near Tavistock. Camden calls him, "without dispute the greatest captain of the age."

Many strange stories are told of him, as that he brought water to Plymouth by pronouncing an incantation over a spring on Dartmoor, and then riding direct to the seaport, whereupon the water followed him, docile as a dog. When he was building Buckland Abbey, every night the devils carried away the stones. Drake got up into a tree and watched. When he saw the devils at work he crowed like a cock. "Dawn coming?" exclaimed a devil. "And there comes the sun!" cried out another, for Drake had lit his pipe; and away they scampered.

Another story is, that he left his wife at Lynton, and was away for so long that she believed him dead, and was about to be married again, when Sir Francis, who was in the Bristol Channel, fired a cannon-ball, that flew in at the church window and fell between her and her intended "second." "None could have done that but Sir Francis," said the lady with a sigh, and so the ceremony was abruptly broken off.

Drake was brought up at sea under Hawkins, and accompanied him on the voyage of 1567, which ended so disastrously. His first independent expedition was in 1572, when he made his memorable expedition to Nombre de Dios.

Four years later Drake started on his voyage of circumnavigation, with five vessels. Disaster and disaffection broke up the little fleet, but he persevered, and on September 26th, 1580, brought the Pelican safely back to Plymouth again; the first English captain who had sailed round the world. Plymouth turned out to welcome him, headed by the Mayor, and S. Andrew's bells rang a merry peal.

The Pelican was crammed with treasure. Drake went to the Thames in her, and was received graciously by the queen. "His ship," says Camden, "she caused to be drawn up in a little creek near Deptford, as a monument of his so lucky sailing round the world. And having, as it were, consecrated it as a memorial with great ceremony, she was banqueted in it, and conferred on Drake the honour of knighthood."

Singularly enough the Spanish Ambassador complained, on the part of his Government, of Drake having ventured into the Pacific; but the queen spiritedly replied that she did not acknowledge grants of strange lands, much less of foreign seas made by the Pope, and that, sail where they might, her good mariners should enjoy her countenance.

In 1585 Drake, with a fleet of twenty-five sail, made another expedition to the West Indies; and his next exploit, performed in 1587, was what he called "singeing the King of Spain's beard." With his fleet he ravaged the coast of Spain, and delayed the sailing of the Armada for a year. The Invincible Armada, as the Spaniards designated it in their pride, set sail from the Tagus on May 29th. It consisted of 130 vessels of all sizes, mounting 2431 guns, and carrying, in addition to the mariners, nearly 20,000 land troops, among whom were 2000 volunteers of the noblest families in Spain. But the fleet was overtaken by a storm off Coruña, and four large ships foundered at sea; on hearing which, that stingy old cat, Elizabeth, at once ordered the admiral, Lord Howard of Effingham, to lay up four of his largest vessels, and discharge their crews. The admiral had the spirit to disobey, saying that rather than do that he would maintain the crews at his own cost. On July 19th, one named Fleming, a Scottish privateer, sailed into Plymouth, with intelligence that he had seen the Spanish fleet off the Lizard. At the moment most of the captains and officers were on shore playing bowls on the Hoe. There was instant bustle, and a call to man the boats. "There is time enough," said Drake, "to play the game out first, and thrash the Spaniards afterwards."

Unfortunately the wind was from the south, but the captains contrived to warp out their ships. On the following day, being Saturday, the 20th of July, they got a full sight of the Armada standing majestically on, the vessels drawn up in the form of a crescent, which, from horn to horn, measured some seven miles.

Their great height and bulk, though imposing to the unskilled, gave confidence to the English seamen, who reckoned at once upon having the advantage in tacking and manoeuvring their lighter craft. The miserable parsimony of Elizabeth, who did not allow a sufficiency of ammunition to the fleet, interfered sadly with the proceedings of the defenders of the English shores. But the story of the Armada belongs to general English history, and need not be detailed here. It is a story, read it often as we may, that makes the blood dance in one's veins.

It has served as the topic of many lines. I will give some not usually quoted, by John O'Keefe, which were set to music by Dr. Arnold:—

"In May fifteen hundred and eighty-eight,

Cries Philip, ' The English I'11 humble;

I've taken it into my Majesty's pate,

And the lion, Oh! down he shall tumble.

The lords of the sea!' Then his sceptre he shook;

'I'll prove it all arrant bravado,

By Neptune! I'll sweep 'em all into a nook,

With th' Invincible Spanish Armado.'

"This fleet started out, and the winds they did blow;

Their guns made a terrible clatter.

Our noble Queen Bess, 'cos her wanted to know,

Quill'd her ruff, and cried, 'Pray what's the matter?'

'They say, my good Queen,' replies Howard so stout,

' The Spaniard has drawn his toledo.

Odds bobbins! he'll thump us, and kick us about,

With th' Invincible Spanish Armado.'

"The Lord Mayor of London, a very wise man,

What to do in the case vastly wondered.

Says the Queen, ' Send in fifty good ships, if you can,'

Says the Lord Mayor, 'I'll send you a hundred!'

Our fire ships soon struck every cannon all dumb,

For the Dons ran to Ave and Credo;

Don Medina roars out, ' Sure the foul fiend is come,

For th' Invincible Spanish Armado.'

"On Effingham's squadron, tho' all in abreast,

Like open-mouth'd curs they came bowling;

His sugar-plums finding they could not digest,

Away they ran yelping and howling.

When Britain's foe shall, all with envy agog,

In our Channel make such a tornado,

Huzza! my brave boys! we're still lusty to flog

An Invincible . . . . Armado."

And here the dotted line will allow of Gallic, Russian, or German to be inserted. Of Spanish there need be no fear. Spain is played out.

A fine bronze statue of Sir Francis by Boehm is on the Hoe, the traditional site of the bowling match, but it is only a replica of that at Tavistock, and lacks the fine bas-reliefs representing incidents in the life of Drake; among others, the game of bowls, and his burial at sea. On the Hoe is also a ridiculous tercentenary monument commemorative of the Armada, and the upper portion of Smeaton's Eddystone lighthouse.

This dangerous reef had occasioned so many wrecks and such loss of life, that Mr. Henry Winstanley, a gentleman of property in Essex, a self-taught mechanician, resolved to devote his attention and his money to the erection of a lighthouse upon the reef, called Eddystone probably because of the swirl of water about it. He commenced the erection in 1696, and completed it in four years. The structure was eminently picturesque, so much so that a local artist at Launceston thought he could not do better than make a painting of it to decorate a house there then in construction (Dockacre), and set it up as a portion of the chimney-piece. The edifice certainly was not calculated to withstand such seas as roll in the Channel, but Winstanley knew only that second-hand wash which flows over miles of mud on the Essex coast, which it submerges, but above which it cannot heap itself into billows.

Winstanley had implicit confidence in his work, and frequently expressed the wish that he might be in his lighthouse when tested by a severe storm from the west. He had his desire. One morning in November, 1703, he left the Barbican to superintend repairs. An old seaman standing there warned him that dirty weather was coming on. Nevertheless, strong in his confidence, he went. That night, whilst he remained at the lighthouse, a hurricane sprang up, and when morning broke no lighthouse was visible; the erection and its occupants had been swept away. Three years elapsed before another attempt was made to rear a beacon. At length a silk mercer of London, named Rudyard, undertook the work. He determined to imitate as closely as might be the trunk of a Scotch pine, and to give to wind and wave as little surface as possible on which to take effect. Winstanley's edifice had been polygonal; Rudyard's was to be circular. Commenced in 1706 and completed in 1709, entirely of timber, the shaft weathered the storms of nearly fifty years in safety, and might have defied them longer but that it was built of combustible materials. It caught fire on the 2nd December, 1755. The three keepers in it did their utmost to extinguish the flames, but their efforts were ineffectual. The lead wherewith it was roofed ran off in molten streams, and the men had to take refuge in a hole of the rock. When they were rescued one of the men went raving mad, broke away, and was never seen again. Another solemnly averred that some of the molten lead, as he stood looking up agape at the fire, had run down his throat as it spouted from the roof. He died within twelve days, and actually lodged within his stomach was found a mass of lead weighing nearly eight ounces. How he had lived so long was a marvel.

Twelve months were not suffered to pass before a third lighthouse was commenced—that of Smeaton. This was of stone, dovetailed together. It was commenced in June, 1757, and completed by October, 1759. This lighthouse might have lasted to the present, had it not been that the rocky foundation began to yield under the incessant beat of the waves.

This necessitated a fourth, from the designs of Mr. (now Sir J.) Douglass, which was begun in 1879 and completed in 1882. The total height is 148 feet. The Breakwater was begun in 1812, but was not completed till 1841.

The neighbourhood of Plymouth abounds in objects of interest and scenes of great beauty. The Hamoaze, the estuary of the Tamar and Tavy combined, is a noble sheet of water. The name (am-uisge), Round about the water, describes it as an almost land-locked tract of glittering tide and effluent rivers, with woods and hills sloping down to the surface. Mount Edgcumbe, with its sub-tropical shrubs and trees, shows how warm the air is even in winter, in spots where not exposed to the sea breeze.

Up the creek of the Lynher (Lyn-hir, the long creek) boats pass to S. Germans, where is a noble church, on the site of a pre-Saxon monastery founded by S. Germanus of Auxerre. The little disfranchised borough contains many objects to engage the artist's pencil, notably the eminently picturesque almshouses.

The noble church has been very badly "restored." The Norman work is fine.

Cawsand, with its bay, makes a pleasant excursion. This was at one time a great nest for smugglers. An old woman named Borlase had a cottage with a window looking towards Plymouth, and she kept her eye on the water. When a preventive boat was visible she went down the street giving information. There was another old woman, only lately deceased, who went by the name of Granny Grylls. When a young woman she was wont to walk to the beach and back carrying a baby that was never heard to wail.

One day a customs officer said to her, "Well, Mrs. Grylls, that baby of yours is very quiet."

"Quiet her may be," answered she, "but I reckon her's got a deal o' sperit in her."

And so she had, for the baby was no other than

ALMS HOUSES, S. GERMANS

a jar of brandy. She was wont by this means to remove "run" liquor from its cache in the sand. A man named Trist had been a notorious smuggler. At last he was caught and given over to the press-cane to be sent on board a man-of-war. Trist bore his capture quietly enough, but as the vessel lay off Cawsand he suddenly slipped overboard and made for a boat that was at anchor, shipped that, and hoisted sail. His Majesty's vessel at once lowered a boat and made in pursuit. After a hard row the sailing smack was come up with and found to be empty. Trist had gone overboard again and swum to a Cawsand fishing smack, where he lay hid for some days. As there was quite a fleet of these boats on the water, the men in His Majesty's service did not know which to search. So Trist got off and was never secured again.

Near Cawsand is a rock with a white sparry formation on it, like the figure of a woman. This is called Lady's Rock, and the fishermen on returning always cast an offering of a few mackerels or herrings to the ledge before the figure.

A curious custom on May Day exists at Millbrook, once a rotten borough, of the boatmen carrying a dressed ship about the streets with music.

An excursion up the Tamar may be made by steamer to the Weir Head. The river scenery is very fine, especially at the Morwell Rocks. On the way Cothele is passed, the ancient and unaltered mansion of the Edgcumbes, rich in carved wood, tapestry, and ancient furniture. It is the most perfect and characteristic mansion of the fifteenth century in Cornwall. Lower down the river is S. Dominic.

Early in the eighth century Indract, with his sister Dominica, Irish pilgrims, and attendants arrived there, and settled on the Tamar. A little headland, Halton, marks a spot where Indract had a chapel and a holy well. The latter is in good condition; the former is represented by an ivy-covered wall. However, the church of Landrake (Llan-Indract) was his main settlement, and his sister Dominica founded that now bearing her name. In the river Indract made a salmon weir and trapped fish for his party. But one of these was a thief and greedy, and carried off fish for his own consumption, regardless of his comrades. There were "ructions," and Indract packed his portmanteau and started for Rome. Whether Dominica accompanied him is not stated, but it is probable that she would not care to be left alone in a strange land, though I am certain she would have met with nothing but kindly courtesy from Cornish-men. The party—all but the thief and those who were in the intrigue with him—reached Rome, and returning through Britain came as far as Skapwith, near Glastonbury, where a Saxon hanger-on upon King Ina's court, hearing that a party of travellers was at hand, basely went to their lodgings and murdered them at night in the hopes of getting loot. Ina, his master, who was then at Glastonbury, came to hear of what had been done, and he had the bodies moved to the abbey. Whether he scolded the man who murdered them, or even proceeded to punish him, we are not told.

Bere Ferrers has a fine church, with some old glass in it and a very singular font, that looks almost as if it had been constructed out of a still earlier capital. Bere Alston was once a borough, returning two members.

On the east side of Plymouth is the interesting Plympton S. Mary, with a noble church; Plympton S. Maurice, with a fine modern screen, and the remains of a castle. Here is the old grammar school where Sir Joshua Reynolds received his instruction, and here also is the house in which he was born. He gave his own portrait to the town hall of the little place—for it also was a borough, and, to the lasting disgrace of Plympton be it recorded, the municipality sold it. The old house of Boringdon has a fine hall. The house has twice been altered, and the last alterations are incongruous. One half of the house has been pulled down. Above it is a well-preserved camp. Ermington Church deserves a visit; it has been well restored. It has a bold post-Reformation screen. Holbeton has also been restored in excellent taste. On Revelstoke a vast amount of money has been lavished unsatisfactorily. Near Cornwood station is Fardell, an old mansion of Sir Walter Raleigh, with a chapel.

The same station serves for the Awns and Dendles cascade, and for a visit to the Stall Moor with its long stone row, also the more than two-mile-long row, leading from the Staldon circle, and the old blowing-houses on the Yealm at Yealm Steps. There the old moulds for the tin lie among the ruins of two of these houses, one above the steps, the other below. A further excursion may be made into the Erme valley, with its numerous prehistoric remains, and to the blowing-house at the junction of the Hook Lake. This is comparatively late, as there is a wheel-pit.

North of Plymouth interesting excursions may be made to the Dewerstone, perhaps the finest bit of rock scenery on Dartmoor, or rather at its edge, where the so-called Plym bursts forth from its moorland cradle. The summit of the Dewerstone has been fortified by a double line of walls. A walk thence up the river will take a visitor into some wild country. He will pass Legis Tor with its hut circles in very fair preservation, Ditsworthy Warren, and at Drizzlecombe, coming in from the north, he will see avenues of stones and menhirs and the Giant's Grave, a large cairn, and a well-preserved kistvaen. By the stream bed below is a blowing-house with its tin moulds. Shavercombe stream comes down on the right, and there may be found traces of the slate that overlay the granite, much altered by heat. From Trowlesworthy Warren a wall, fallen, extends, in connection with numerous hut circles, as far as the Yealm. For what purpose it was erected, unless it were a tribal boundary, it is impossible to discover.

A visitor to the Dewerstone should not fail to descend through the wood to the Meavy river, and follow it down to Shaugh Bridge.

An interesting house is Old Newnham, the ancient seat of the Strode family.

Hard by is Peacock Bridge. Here a fight took

place, according to tradition, between a Parker and a Strode, with their retainers, relative to a peacock, and Strode had his thumb cut off in the fray.

Buckland Monachorum also is within reach, the church converted into a mansion.

Meavy Church contains early and rude carving. Sheepstor stands above an artificial lake, the reservoir that supplies Plymouth with water. This occupies the site of an ancient lake, that had been filled with rubble brought down by the torrents from the moor.

A delightful walk may be taken by branching from the Princetown road to Nosworthy Bridge, passing under Leather Tor and following Deancombe, then ascending Combshead Tor to an interesting group of prehistoric remains, a cairn surrounded by a circle of stones, and a stone row leading to a chambered cairn. By continuing the line north-east Nun's or Siward's Cross will be reached in the midst of utter desolation. Far away east is Childe's Tomb, a kistvaen.

The story is that Childe, a hunter, lost himself on the moor. Snow came on, and he cut open his horse, and crept within the carcass to keep himself warm. But even this did not avail.

So with his finger dipp'd in blood,

He scrabbled on the stones:

"This is my will, God it fulfil,

And buried be my bones.

Whoe'er he be that findeth me,

And brings me to a grave,

The lands that now to me belong

In Plymstock he shall have."

END OF VOL I.

PLYMOUTH

WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON

PRINTERS