A Wayfarer in China/Chapter 11

CHAPTER XI

FROM THE GREAT RIVER TO THE GREAT WALL

AT Ichang, a thousand miles from Shanghai, I met the West, modern comforts, bad manners, and all. Situated at the eastern end of the gorges, this town of thirty thousand Chinese inhabitants and a handful of Europeans is just where all the merchandise going upstream must be shifted from the light-draft steamers of the lower Yangtse to the native junks of forty to a hundred tons which are still the only freight boats that venture regularly through the rapids and whirlpools of the upper waters of the Great River. So the water front of Ichang is a busy scene at all times, and in the winter season the boats are packed together sardine fashion. When the railway is put through, all the river traffic will cease, but Ichang proposes to control the new route as it has the old, and already an imposing station has been completed, even though only a few miles of iron rail have been laid down.

I shifted my belongings directly from the wu-pan to the Kweilu, a Butterfield & Swire boat leaving the same evening. It was very comfortable, although crowded, as everything seems to be in China. Ichang stands at the extreme eastern edge of the tangle of mountains that stretch across Szechuan to the Tibetan plateau, and just below this point the scenery changes, the hills dwindle, and the valley opens into the wide flat plains of the lower Yangtse. It is a merciful arrangement, allowing the eyes and brain a chance to recover their tone after the strain of trying to take in the wonders of the gorges, and I was glad for the open, vacant land, thankful that there was nothing to look at.

The second morning in the early dawn we moored off Hankow, where I planned to stay a day or two before turning northward. Hankow, Hanyang, Wuchang, these three cities lie at the junction of the Han and the Yangtse, having, all told, a population of some two millions. Located on the Yangtse, at the mouth of the Han, one of the great waterways of China, halfway between Shanghai and Ichang, and a little more than halfway from Peking to Canton, and at present the terminus of the Peking railway, which in good time will be extended to Canton, the future of these cities is assured. Each of the three has some special claim to preëminence, but the greatest of them is Hankow. Hanyang's chimneys are preparing to rival those of Bombay, and it boasts the largest ironworks in China. Wuchang is the provincial capital, and the seat of the viceroy or governor, as it happens, and its mint and arsenal are the most important in the south, while Hankow is the trading centre, and the headquarters of the great banking and shipping concerns.

When I was there in early July of last year I noticed only the look of substantial prosperity about the place, and the comfortable bustle and stir in the streets. Chinese and Europeans alike seemed intent on making money, pound-wise or cash-wise. The one matter of concern was the high water in the river, here nearly a mile wide. Already it was almost up to the top of the "bund"; a few inches more and it would flood the lowland, destroying life and property, and stopping all business. There were no outward signs of commotion underneath, but in about three months the viceroy's yamen was in flames, shops and offices were looted, and the mint and arsenal in the hands of the Revolutionary party. One stroke had put it in possession of a large amount of treasure, military stores, and a commanding position.

I planned to stay in Hankow just long enough to pack a box for England, and efface a few of the scars of inland travel before confronting whatever society might be found in Peking in midsummer, but rather to my dismay I found the weekly express train left the day after my arrival. It was out of the question to take that, and apparently I would have to wait over a week unless I dared try the ordinary train that ran daily, stopping two nights on the road. But there seemed many lions in the way. It would be quite impossible to go by this train unless I could take all my things into the carriage with me; nothing was safe in the luggage van. It would be a long and tedious journey, and I could get nothing to eat on the way, and of course it would be impossible to put up at Chinese inns at night. But face the Eastern lions and they generally turn to kittens. Travelling by way trains had no terrors for me, it would give me a chance to see the country, and it was for that I had come to China, and I knew I could manage about my things; but the Chinese inn was something of a difficulty, as I was leaving interpreter and cook in Hankow. I jumped into a rickshaw and by good luck found the genial superintendent, M. Didier, at the station. Mais oui, I might stop in the train at night; mais oui, the little dog could be with me; mais oui, I could certainly manage a trunk in my compartment. And he did even better than his word, wiring ahead to the nights' stopping-places, Chu-ma-tien and Chang-te-ho, and when the train pulled in at each place, I was charmingly welcomed by the division superintendent with an invitation from his wife to put up with them; and so instead of two nights in the stuffy sleeping-compartment of the express train, I had two enjoyable evenings in French homes, and long nights in a real bed. It was indeed a bit of France that these delightful Frenchwomen had created in the plain of Central China; books and journals, dogs and wines from home, and French dishes skilfully prepared by Chinese hands. But the houses where they lived opened out of the strongly walled station enclosure; it would not take long to put it in condition to stand a siege. No one in China forgets the days of 1900.

The train was of the comfortable corridor sort. Most of the time I was the only European, and the only person in the first class, but the second and especially the third were crowded full, although the passengers did not seem about to flow out of the windows, feet foremost, as so often on an Indian railway. The Chinese is beset by many fears, superstitious fears or real mundane ones, but he has the wit to know a good thing when he sees it, and it does not take him long to overcome any pet fear that stands in the way of possessing it. In 1870 the first Chinese railway was built by the great shipowners of the East, Jardine, Mattheson & Co. It was only twelve miles long, connecting Shanghai with Woosung. At first there was no trouble, then certain native interests, fearing the competition, stirred up the people by the usual methods, finally clinching the opposition by a suicide (hired) under a train; so in the end the Government bought out the English firm and dismantled the railway. That was forty years ago, and to-day all that stands in the way of gridironing China with iron highways is the lack of home capital and the perfectly reasonable fear of foreign loans. The Chinese want railways, and they want to build them themselves, but they have not got the money, and for the moment they prefer to go without rather than put themselves in the power of European capitalists and European governments. And who can blame them?

The Six Power Railway Loan of 1908 proved the undoing of the Manchus, and the inevitable sequence, the appointing of European and American engineers,—to the American was assigned the important section between Ichang and Chengtu,—was bringing matters to a head before I left China. The Changsha outbreak in the early summer was directed against the Government's railway policy, represented for the moment in the newly appointed Director of Communications, the Manchu Tuan Fang, who visited the United States in 1906 as a member of the Imperial Commission. Many will remember the courteous old man, perhaps the most progressive of all the Manchu leaders. I had hoped to meet him in China, but on inquiring his whereabouts when in Shanghai I was told that he had been degraded from his post as Viceroy of Nanking and was living in retirement. A few weeks later the papers were full of his new appointment, extolling his patriotism in accepting an office inferior to the one from which he had been removed. But delays followed, and when the rioting occurred in Changsha he had not yet arrived at headquarters in Hankow. It was said openly that he was afraid. On my way north the train drew up one evening on a siding, and when I asked the reason I was told a special train was going south bearing His Excellency Tuan Fang to his post. He had just come from a conference at Chang-te-ho with Yuan Shih Kai, who was living there in retirement nursing his "gouty leg." If only one could have heard that last talk between the two great supporters of a falling dynasty.

And one went on his way south to take up the impossible task of stemming the tide of revolution, and before four months were past he was dead, struck down and beheaded by his own soldiers in a little Szechuan town, while the other, biding his time, stands to-day at the head of the new Republic of the East.

The Lu-Han railway, as the Peking-Hankow line is called, crosses three provinces, Hupeh, Honan, and Chihli. Save for low hills on the Hupeh frontier, it runs the whole way through a flat, featureless country, cultivated by hand, almost every square foot of it. Seven hundred miles of rice- and millet-fields and vegetable gardens unbroken by wall or hedge; nothing to cast a shadow on the dead level except an occasional walled town or temple grove! And the horrible land was all alive with swarming, toiling, ant-hill humanity. It was a nightmare.

On the second day we reached the Hoang Ho, China's sorrow and the engineer's despair. The much-discussed bridge is two miles long, crossing the river on one hundred and seven spans. As the train moved at snail's pace there was plenty of time to take in the desolate scene, stretches of mudflats alternating with broad channels of swirling, turbid water; and, unlike the Yangtse, gay with all sorts of craft, the strong current of the Yellow River rolled along undisturbed by sweep or screw.

Once across the Hoang Ho and you enter the loess country, dear to the tiller of the soil, but the bane of the traveller, for the dust is often intolerable. But there was little change in scenery until toward noon of the following day, when the faint, broken outlines of hills appeared on the northern horizon. As we were delayed by a little accident it was getting dark when we rumbled along below the great wall of Peking into the noisy station alive with the clamour of rickshaw boys and hotel touts. In fifteen minutes I was in my comfortable quarters at the Hôtel des Wagons Lits, keen for the excitement of the first view of one of the world's great historic capitals.

Peking is set in the middle of the large plain that stretches one hundred miles from the Gulf of Pechihli to the Pass of Nankow. On the north it is flanked by low hills, thus happily excluding all evil influences, but it is open to the good, that always come from the south. So from a Chinese point of view its location is entirely satisfactory, but a European might think it was dangerously near the frontier for the capital city of a great state. Years ago Gordon's advice to the Tsungli Yamen was, "Move your Queen Bee to Nanking." And just now the same thing is being said, only more peremptorily, by some of the Chinese themselves. But for the moment lack of money and fear of Southern influences have carried the day against any military advantage, and the capital remains where it is. Perhaps the outsider may be permitted to say she is glad, for Nanking could never hope to rival the Northern city in charm and interest.

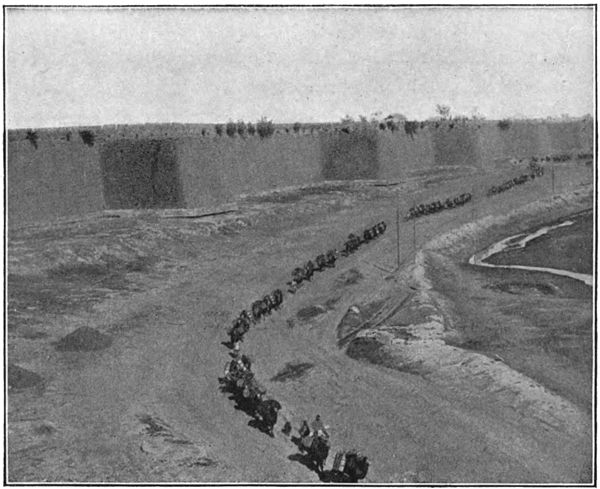

The most wonderful thing in Peking is the wall. That is what first holds your attention, and you never for a moment forget it. There it stands, aloof and remote, dominating the city it was set to defend, but not a part of it. Huge, massive, simple, it has nothing in common with the gaudy, over-ornamented, unrestful buildings of the Chinese, and as you enter its shadow you seem to have passed into a different world.

Often before breakfast I climbed to the top of the wall beyond the Water Gate for a run with Jack before the heat of the day set in. It was a glorious place for a morning walk. The wall is some forty feet high, and along the top runs a broad path enclosed by crenellated parapets. From here your vision ranges north and south and east and west; no smoke, no tall chimneys, no towering, hideous buildings to break and spoil the view.

North you look over the Tartar City, which is really three cities, all walled, and one within the other like the boxes of a puzzle, the Tartar City enclosing the Imperial City, and that in turn the Forbidden City. If you stand under the many-storied tower that surmounts the Chien-Men, you look straight along the road that leads through the vermilion walls, right into the Purple City, the heart of Peking. In Marco Polo's time the middle door of the great portal was never opened save to admit the emperor, and that was still true a few months ago, but last winter a day came when the bars rolled back, and there entered no emperor, no ruler, but the representative of the People's Assembly, and then a placard was posted announcing that hereafter the door was open to every one, for all China belonged to the people. For a matter-of-fact man the Chinese has a very dramatic way of doing things.

Turning southwards from the top of the wall you look beyond the Chinese City, which is nothing but a walled suburb, to the gleaming white walls of the Temple of Heaven, half buried in the trees. There each year the emperor comes to offer sacrifices to his ancestors, the crowning expression of China's truest religion, ancestor worship. In a few months only, Prince Ch'un, the Regent, whom you have just met driving in state through the Imperial City, standing among his ministers, and acting for the baby emperor, will take the oath, not to the people of China, nor to any representative assembly, but to the imperial ancestors to accept and obey the new constitutional principles. "I, your descendant, P'u Yi," he will say, "have endeavoured to consummate the constitutional programme, but my policy and my choice of officials have not been wise. Hence the recent troubles. Fearing the fall of the sacred dynasty I accept the advice of the National Assembly, and I vow to uphold the nineteen constitutional articles, and to organize a Parliament.…I and my descendants will adhere to it forever. Your Heavenly Spirits will see and understand."There is unfailing charm and interest in the view over Peking from the top of the wall. Chinese cities are generally attractive, looked down upon from above, because of the many trees, but here the wealth of foliage and blaze of colour are almost bewildering; the graceful outlines of pagoda and temple, the saucy tilt of the roofs, yellow and green, imperial and princely, rising above stretches of soft brown walls, the homes of the people, everything framed in masses of living green; and stretching around it all, like a huge protecting arm, the great grey wall. You sigh with satisfaction; nowhere is there a jarring note; and then—you turn your eyes down to the grounds and buildings of the American Legation at your feet, clean, comfortable, uncompromising, and alien. Near you paces to and fro a soldier, gun on shoulder, his trim figure set off by his well-fitting khaki clothes, unmistakably American, unmistakably foreign, guarding this strip of Peking's great wall, where neither Manchu nor Chinese may set foot. And then your gaze travels along the wall, to where, dimly outlined against the horizon, you discern the empty frames of the wonderful astronomical instruments that were once the glory of Peking, now adorning a Berlin museum, set up for the German holiday-makers to gape at. After all, there are discordant notes in Peking.

Down in the streets there is plenty of life and variety. Mongol and Manchu and Chinese jostle each other in the dust or mud of the broad highways. The swift rickshaws thread their way through the throng with amazing dexterity. Here the escort of a great official clatters by, with jingling swords and flutter of tassels, there a long train of camels fresh from the desert blocks the road. The trim European victoria, in which sits the fair wife of a Western diplomat, fresh as a flower in her summer finery, halts side by side with the heavy Peking cart, its curved matting top framing the gay dress and gayer faces of some Manchu women. And the kaleidoscopic scene moves against a background of shops and houses gay with paint and gilding. The life, the colour, the noise are bewildering; your head begins to swim. And then you look away from it all to the great wall. There it stands, massive, aloof, untouched by the petty life at its foot. And you think of all it has looked upon; what tales of men and their doings it could tell. And you ask the first European you meet, or the last,—it is always the same,—about the place and its history, and he says, "Oh, yes, Peking is full of historical memorials which you must not fail to see"; but they always turn out to be the spots made famous in the siege of the legations. To the average European, Peking's history begins in 1900; you cannot get away from that time, and after a while you tire of it, and you tire, too, of all the bustle and blaze of colour. And you climb again to the top of the wall that seems to belong to another world, and you look off toward the great break in the hills, to Nankow, the Gate of the South. On the other side the road leads straight away to the Mongolian uplands where the winds blow, and to the wide, empty spaces of the desert.

So you turn your back upon Peking, and the railway takes you to Kalgan on the edge of the great plateau. It is only one hundred and twenty-five miles away, but you spend nearly a whole day in the train, for you are climbing all the way. And time does not matter, for it is interesting to see what the Chinese can do in railway building and railway managing, all by themselves. The Kalgan-Peking railway was the first thing of the kind constructed by the Chinese, and the engineer in chief, Chang-Tien-You, did the work so well (he was educated in America, one of the group that came in the early seventies) that he was later put in charge of the railway that was to be built from Canton northwards. It seems to be an honest piece of work; at any rate, the stations had a substantial look.

At the grand mountain gateway of Nankow you pass under the Great Wall, which crosses the road at right angles, and as you slowly steam across the plateau on the outer side, you see it reappearing from time to time like a huge snake winding along the ridges. Old wall, new railway; which will serve China best? One sought to keep the world out, the other should help to create a Chinese nation that will not need to fear the world.

My first impression of Kalgan was of a modern European station, and many lines of rails; my last and most enduring, the kindness of the Western dweller in the East to the stray Westerner of whose doings he probably disapproves. Between these two impressions I had only time to gain a passing glimpse of the town itself. It is a busy, dirty place, enclosed in high walls, and cut in two by the rapid Ta Ho. A huddle of palaces, temples, banks lies concealed behind the mud walls that hem in the narrow lanes, for Kalgan has been for many years an important trading centre, and through here passes the traffic across the Gobi Desert. In the dirty, open square crowded with carts are two or three incongruous Western buildings, for the foreigner and his ways have found the town out. Of the small European community, missionaries of different nationalities and Russians of various callings form the largest groups. The energetic British American Tobacco Company also has its representatives here, who were my most courteous hosts during my two days' stay.

Kalgan stands hard-by the Great Wall; here China and Mongolia meet, and the two races mingle in its streets. Nothing now keeps them in or out, but the barrier of a great gulf is there. Behind you lie the depressing heat and the crowded places of the lowlands. Before you is the untainted air, the emptiness of Mongolia. You have turned your back on the walled-in Chinese world, walled houses, walled towns, walled empire; you look out on the great spaces, the freedom of the desert.