A history of the gunpowder plot/Chapter 17

CHAPTER XVII

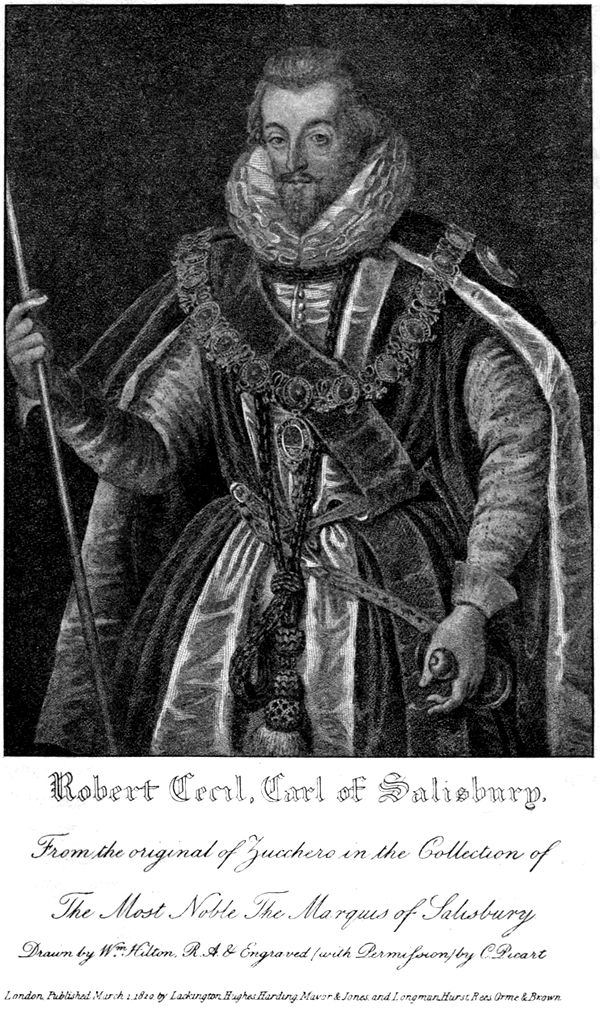

LORD SALISBURY'S ACCOUNT OF THE PLOT

ROBERT CECIL, Earl of Salisbury, Secretary of State, has left behind him an account of the Plot, which may certainly claim to be the earliest historical record of the great event, for the manuscript is dated only four days later than the fatal fifth of November. This account is contained in a letter sent by him to Sir Charles Cornwallis, the British Ambassador in Spain.[1] I reproduce below the whole of the despatch, which is of great interest and historical importance—

'It hath pleased Almighty God out of his singular goodness to bring to light the most cruel and detestable Conspiracy against the person of his Majesty and the whole state of this Realm that ever was conceived by the heart of man, at any time or in any place whatsoever. By the practice there was intended not only the extirpation of the King's Majesty and his royal issue, but the whole subversion and downfall of this Estate; the plot being to take away at one instant the King, Queen, Prince, Council, Nobility, Clergy, Judges, and the principal gentlemen of the Realm, as they should have been altogether assembled in the Parliament-House in Westminster, the 5th of November, being Tuesday. The means how to have compassed so great an act, was not to be performed by strength of men, or outward violence, but by a secret conveyance of a great quantity of gunpowder in a vault under the Upper House of Parliament, and so to have blown up all out of a clap, if God out of his mercy and just revenge against so great an abomination had not destined it to be discovered, though very miraculously, even some 12 hours before the matter should have been put into execution. The person that was the principal undertaker of it is one Johnson, a Yorkshire man, and servant to one Thomas Percy, a Gentleman-Pensioner to his Majesty, and a near[2] kinsman to the Earl of Northumberland.

'This Percy had about a year and a half ago hired a part of Vyniard House in the Old Palace, from whence he had access into this vault to lay his wood and coal; and, as it seemeth now, had taken this place on purpose to work some mischief in a fit time. He is a Papist by profession, and so is his man Johnson,[3] a desperate fellow, who of late years he took into his service. Into this vault Johnson had at sundry times very privately conveyed a great quantity of powder, and therewith  FAWKES' LANTERN.

FAWKES' LANTERN.

(Preserved at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) filled two hogsheads, and some 32 small barrels; all which he had cunningly covered with great store of billets and faggots; and on Monday, at night, as he was busy to prepare his things for execution, was apprehended in the place itself,[4] with a false lantern,[5] booted and spurred. There was likewise found some small quantity of fine powder for to make a train, and a piece of match, with a tinder-box to have fired the train when he should have seen time, and so to have saved himself from the blow, by some half an hour's respite that the match should have burned.

'Being taken and examined, he resolutely confessed the attempt, and his intention to put it into execution (as is said before) that very day and hour when his Majesty should make his oration in the Upper House. For any complices in this horrible act, he denieth to accuse any; alleging, that he had received the Sacrament a little before of a Priest, and taken an oath never to reveal any; but confesseth that he hath been lately beyond the seas, both in the Low Countries and France, and there had conference with divers English priests; but denieth to have made them acquainted with this purpose.

'It remaineth that I add something, for your better understanding, how this matter came to be discovered. About 8 days before the Parliament should have begun, the Lord Mounteagle received a letter about six o'clock at night (which was delivered to his footman in the dark to give him) without name or date, and in a hand disguised; whereof I send you a copy, the rather to make you perceive to what a strait I was driven. As soon as he imparted the same unto me, how to govern myself, considering the contents and phrase of that letter I knew not; for when I observed the generality of the advertisment and the style, I could not well distinguish whether it were frenzy or sport; for from any serious ground I could hardly be induced to believe that that proceeded, for many Reasons; 1st., because no wise man could think my Lord [6] to be so weak as to take any alarm to absent himself from Parliament upon such a loose advertisement: secondly, I considered, that if any such thing were really intended, that it was very improbable that only one nobleman should be warned and no more. Nevertheless, being loath to trust my own judgment alone, and being always inclined to do too much in such a case as that is, I imparted the letter to the Earl of Suffolk, Lord Chamberlain, to the end I might receive his opinion;[7] whereupon perusing the words of the letter, and observing the writing (that the blow should come without knowledge who hurt them), we both conceived that it could not be more proper than the time of Parliament, nor by any other way like to be attempted than with powder, whilst the King was sitting in that Assembly; of which the Lord Chamberlain conceived more probability, because there was a great vault under the said chamber, which was never used for any thing but for some wood and coal, belonging to the Keeper of the Old Palace. In which consideration, after we had imparted the same to the Lord Admiral, the Earl of Worcester, the Earl of Northampton, and some others, we all thought fit to impart it to the King, until some 3 or 4 days before the Sessions. At which time we shewed his Majesty the letter, rather as a thing we could not conceal because it was of such a nature, than anything persuading him to give further credit unto it until the place had been visited.

'Whereupon his Majesty, who hath a natural habit to contemn all false fears,[8] and a judgment so strong as never to doubt anything which is not well warranted by Reason, concurred thus far with us, that seeing such a matter was possible, that should be done which might prevent all danger or nothing at all. Hereupon it was moved, that till the night before his coming, nothing should be to interrupt any purpose of theirs that had any such devilish practice, but rather to suffer them to go on till the end of the day.[9] And so, Monday, in the afternoon, the Lord Chamberlain, whose office is to see all places of assembly put in readiness when the King's person should come, taking with him the Lord Mounteagle, went to see all the places in the Parliament House, and took also a slight occasion to peruse the vault; where, finding only piles of billets and faggots heaped up, his Lordship still inquiring only who owned the same wood, observing the proportion to be somewhat more than the housekeeper was likely to lay in for his own use: And when answer was made that it belonged to one Mr. Percy, his Lordship straight conceived some suspicion in regard of his person; and the Lord Mounteagle taking some notice, that there was great profession between Percy and him, from which some inference might be made that it was the warning of a friend, my Lord Chamberlain resolved absolutely to proceed in a search, though no other materials were visible. And being returned to the Court, about 5 a clock took me up to the King and told him, that though he was hard of belief that any such thing was thought, yet in such a case as this, whatsoever was not done to put all out of doubt was as good as nothing. Whereupon it was resolved by his Majesty, that this matter should be so carried as no man should be scandalized by it, nor any alarm taken for any such purpose. For the better effecting whereof, the Lord Treasurer, the Lord Admiral, the Earl of Worcester, and we two agreed, that Sir Thomas Knyvet, should under a pretext for stolen and embezzled goods both in that place and other houses thereabouts, remove all that wood, and so to see the plain ground under it.

'Sir Thomas Knyvet going thither about mid-night unlocked for into the vault, found that fellow Johnson newly come out of the vault, and without asking him more questions stayed him; and having no sooner removed the wood he perceived the barrels, and so bound the catiff fast; who made no difficulty to acknowledge the act, nor to confess clearly, that the morrow following it should have been effected. And thus have you a true narration from the beginning of this, which hath been spent in examinations of Johnson, who carrieth himself without any fear or perturbation, protesting his constant resolution to have performed it that day whatsoever had come of it; principally for the institution of the Roman religion, next out of hope to have dissolved this Government, and afterwards to have framed such a State as might have served the appetite of him and his complices. And in all this action he is no more dismayed, nay scarce any more troubled, than if he were taken for a poor robbery upon the highway. For notwithstanding he confesseth all things of himself, and denieth not to have some partners in this particular practice, (as well appeareth by the flying of divers Gentlemen upon his apprehension known to be notorious Recusants), yet could no threatening of torture draw from him any other language than this, that he is ready to die, and rather wisheth ten thousand deaths, than willingly to accuse his master or any other; until by often reiterating examinations, we pretending to him that his master was apprehended, he hath come to plain confession, that his master kept the key of that cellar whilst he was abroad; had been in it since the powder was laid there, and inclusive confessed him a principal actor in the same.

'In the meantime, we have also found out, (though he denied it long) that on Saturday night the third of November, he[10] came post out of the north; that this man[11] rid to meet him by the way; that he dined at Sion[12] with the Earl of Northumberland on Monday; that as soon as the Lord Chamberlain had been in the vault that evening, this fellow went to his master about six of the clock at night, and had no sooner spoken with him but he fled immediately, apprehending straight that to be discovered, which at that time was held rather unworthy belief, though not unworthy the after trial. In which I must need do my Lord Chamberlain his right, that he could take no satisfaction until he might search that matter to the bottom; wherein I must confess I was much less forward; not but that I had sufficient advertisement, that most of those that now are fled (being all notorious Recusants) with many other of that kind, had a practice in hand for some stir this Parliament; but I never dreamed it should have been in such nature, because I never read nor heard the like in any State to be attempted ingross by any conspiration, without some distinction of persons.

'I do now send you some proclamations, and withal think good to advertize you, that those persons named in them, being most of them gentlemen spent in their fortunes, all inward with Percy and fit for all alterations, have gathered themselves to a head of some four score or 100 horse, with purpose (as we conceive) to pass over  Seas; whereupon it hath been though meet in policy of State (all circumstances considered) to commit the Earl of Northumberland to the Archbishop of Canterbury, there to be honourably used, until things be more quiet: Whereof if you shall any judgment made, as if his Majesty or his Council could harbour a thought of such a savage practice to be lodged in such a Nobleman's breast, you shall do well to suppress it as a malicious discourse and 'invention, this being only done to satisfy the world, that nothing be undone which belongs to policy of State, when the whole Monarchy was proscribed in dissolution; and being no more than himself discreetly approved as necessary, when he received the sentence of the Council for his restraint.

Seas; whereupon it hath been though meet in policy of State (all circumstances considered) to commit the Earl of Northumberland to the Archbishop of Canterbury, there to be honourably used, until things be more quiet: Whereof if you shall any judgment made, as if his Majesty or his Council could harbour a thought of such a savage practice to be lodged in such a Nobleman's breast, you shall do well to suppress it as a malicious discourse and 'invention, this being only done to satisfy the world, that nothing be undone which belongs to policy of State, when the whole Monarchy was proscribed in dissolution; and being no more than himself discreetly approved as necessary, when he received the sentence of the Council for his restraint.

'It is also fit that some martial men should presently repair down to those countries where the " Robin Hoods" are assembled, to encourage the good and to terrify the bad. In which service the Earl of Devonshire is used, and commission going forth for him as General; although I am easily persuaded, that this faggot will be burned to ashes before he shall be 20 miles on his way. Of all which particulars I thought fit to acquaint you, that you may be able to give satisfaction to the State[13] wherein you are; and so I commit you to God.

'Your assured loving friend,

'(Signed) SALISBURY.

'From the Court at Whitehall.

'Postscript.

'Although all ports and passages are stopped for some time as well as for Ambassadors as others, yet I have thought good to advertize you hereof with the speediest, the rather because his Majesty would have you take occasion to advertize the King his brother[14] of this miraculous escape.

'Postscript.

'Since the writing of this letter, we have assured news that those traitors are overthrown by the Sheriff of Worcestershire, after they had betaken themselves for their safety in a retreat to the house of Stephen Lyttleton in Staffordshire. The house was fired by the Sheriff; at the issuing forth Catesby was slain; Percy sore hurt, Grant and Winter burned in their faces with gunpowder; the rest are either taken or slain; Rookewood or Digby are taken.'

It is much to be deplored that this letter to Cornwallis has not met with closer attention at the hands of historians, for to those able to read, as it were, between the lines, the contents reveal some important facts about the discovery of the Plot.

For example, this letter completely contradicts the old story that the Government knew nothing of a Plot till the arrival of Mounteagle's letter, for Lord Salisbury distinctly says, 'I had sufficient advertisement that most of those that now are fled (being all notorious Recusants) with many other of that kind, had a practice in hand for some stir this Parliament.' As to the writer's excuse that he was less forward in causing a strict inquiry to be made than the Lord Chamberlain, it is easy to see that Lord Salisbury's object was not to show his hand too much, but to let others obtain some credit for discovering what was already known to him. That Lord Salisbury was well posted up in the facts, and felt quite secure as to the result of his preparations, is evident from the account he renders as to how he determined not to inform the King until the last moment. His astuteness in making no open move thus deceived Catesby, and culminated in the ruin of the unsuspecting conspirators.

Salisbury's language in regard to Percy ends, if further contradiction were necessary, the absurd theory propounded by a Jesuit author that the Government did not wish Percy to be taken alive because he 'knew too much.' Lord Salisbury's anxiety, on the contrary, to capture Percy alive is obvious. He evidently hoped that under examination, and probably after torture, Percy would be compelled to incriminate his patron, Lord Northumberland. How little the Government knew of Faukes, well posted up though they were as to the antecedents of the other plotters, can be gathered from the circumstance that Salisbury terms him 'Johnson' throughout the letter.

- ↑ Cornwallis was our Ambassador from 1605 till 1609. In 1614 he was imprisoned in the Tower. He died in December, 1629. A man of straightforward character, he was badly treated by King James.

- ↑ This he was not, and the false statement illustrates Salisbury's unscrupulous methods of incriminating the innocent Northumberland.

- ↑ Guy Faukes.

- ↑ This does not tally with other accounts, which say that he was captured outside the building.

- ↑ This lantern is now preserved in the Ashmolean collection at Oxford.

- ↑ Lord Mounteagle.

- ↑ Cecil's story that the receipt of the letter took him entirely by surprise, and that its contents proved an enigma to him, is very cleverly told, but is a concoction not to be believed. He omits the fact that, although the letter was received late at night, he lost not a minute in placing it before his colleagues, who were all (suspiciously) close at hand when Mounteagle arrived post haste from Hoxton.

- ↑ This the King most certainly had not. He was ever suspicious, and prone to take unnecessary alarm.

- ↑ This stratagem resulted in the capture of the plotters, for it deceived them into thinking that their particular plan had not been discovered, and encouraged them to persevere to the end.

- ↑ Thomas Percy.

- ↑ Faukes.

- ↑ Sion House, Isleworth.

- ↑ Spain.

- ↑ The King of Spain.