A history of the gunpowder plot/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

SUBORDINATE CONSPIRATORS

OF Christopher Wright,[1] the younger brother of John, little is known. He was actively engaged in the Essex revolt, and had been employed as one of the delegates of the Jesuits on the mission to the Court of Spain. Born in 1571, he seems to have followed faithfully the fortunes of his brother, but to have taken no leading part in the management of the plot. Robert Keyes, his friend, deserves greater attention, for he commenced life as a pronounced Protestant, his father being a Protestant clergyman, but his mother, a daughter of Sir Robert Tyrwhit, came of a Roman Catholic stock, though whether she influenced him in his resolve to become a Roman Catholic we are not told. He married Christiana, widow of Thomas Groome, and for some years previous to the plot lived with her at Turvey, Bedfordshire, the residence of Lord Mordaunt, a Catholic peer, to whose children his wife was governess. According to Father Gerard, he was 'a grave and sober man, and of great wit and sufficiency, as I have heard divers say that were well acquainted with him. His virtue and valour were the chiefest things wherein they could expect assistance from him; for, otherwise, his means were not great.' His close intimacy with Lord Mordaunt brought that nobleman into grave trouble with the Government, in the same way as Percy's intimacy with his patron, Northumberland, proved injurious to that unsuspecting peer. At Catesby's advice, the care of the conspirators' house at Lambeth, used by them as their London rendezvous, was entrusted to the stern and undaunted Keyes.

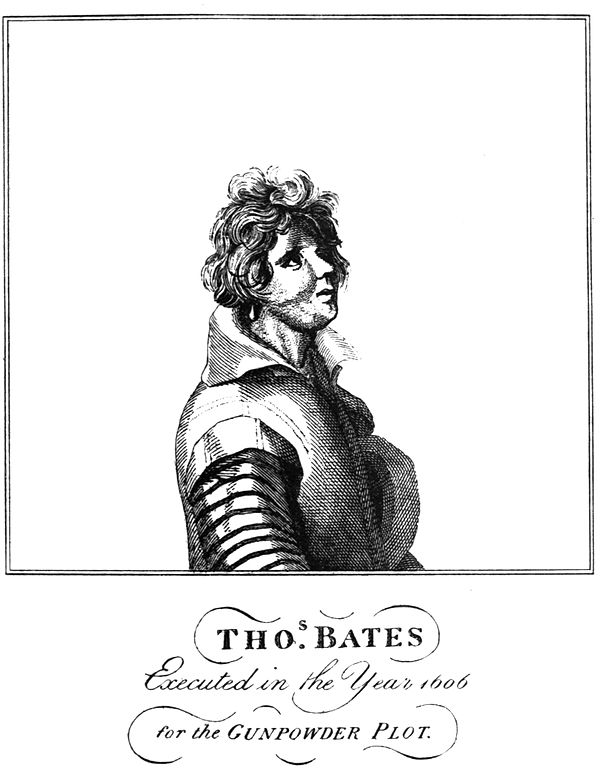

Thomas Bates sprang from a very different origin to that of his confederates. He was an old and faithful servant of Catesby, to whom he was devotedly attached, and by whom he was admitted into the confederacy, as one upon whom his powerful master could implicitly rely, and who would prove useful as a humble messenger carrying despatches between the conspirators. According to Sir Edward Coke (Attorney-General), who appeared for the Crown at Bates's trial, the manner of his reception was as follows—

'Concerning Thomas Bates, who was Catesby's man, as he was wound into this treason by his master, so was he resolved, when he doubted of the lawfulness thereof, by the doctrine

'Bates answer'd," that he thought they went about some dangerous matter, whatsoever the particulars were: whereupon they asked him again what he thought the business might be; and he answered that he thought they intended some dangerous matter about the Parliament House, because he had been sent to get a lodging near unto that place.

'Then did they make the said Bates take an oath to be secret in the action; which being taken by them, they then told him it was true, that they were to execute a great matter; namely, to lay powder the Parliament House to blow it up.'

John Grant was a Warwickshire gentleman, his residence, Norlook, being situated between Warwick and Stratford. He was well descended, and connected with several old families in the shires of Warwick and Worcester. Although, according to Father Greenway, of a taciturn disposition, he was of a very fierce and mettlesome temper, in the opinion of Gerard. He was implicated with his friends in the Essex rebellion.[3] Catesby's chief reason for enrolling him as a member of the confederacy, seems to have been the fact that Grant's 'walled and moated' residence would provide an excellent rendezvous for those of the conspirators who were to foment an armed rising in the Midlands. He was a devout Roman Catholic, and on the eve of his death on the scaffold expressed himself 'convinced that our project was so far from being sinful' as to afford an 'expiation for all sins committed by me.'

Robert Winter was the elder brother of Thomas, and was a son-in-law of John Talbot,[4] of Grafton, an influential Roman Catholic, whom the conspirators tried vainly to inveigle into connection with their schemes. He possessed the estate of Huddington, in Worcestershire.[5] On first hearing of the plot, he expressed his utmost detestation of the whole concern; but eventually permitted himself to be cajoled into joining it, probably at the instance of his brother, His heart, however, was never in the business, and he took no part in stowing away the gun-powder. He deserted Catesby before the last stand was made at Holbeach. He cannot be considered in the light of either an active or a willing conspirator, but merely of one who possessed an unhappy, though guilty, knowledge of what was going on; for which, after months of terrible anxiety and perplexity, he paid forfeit with his life.

Ambrose Rookewood, born in 1577, was a gentleman of an old family in Suffolk, which had remained Roman Catholic, notwithstanding the severe persecution of several of its members under Elizabeth.[6] Ambrose was the eldest son of his parents, and on his father's death, some four years before he joined the conspiracy, he became a very wealthy man. His wife, Elizabeth Tyrwhit, was a lady of remarkable beauty, by whom he had two sons. The elder of these quickly wiped out the stain on his name incurred by his father's treason, and was actually knighted by the very king whom his father had plotted to destroy. Rookewood was drawn into the plot by Catesby, whom he 'loved and respected as his own life' and who overcame his scruples against 'taking away so much blood' by assuring him, so it seems, that the scheme had received the approbation of his confessor. In Rookewood's stable at Coldham Hall there was an especially fine stud of horses, and Catesby, who selected each conspirator for some particular reason likely to prove advantageous to his plans, had long coveted Rookewood's steeds.

That a man like Ambrose Rookewood should have been seduced into treason is to be deplored. Notwithstanding his persecution at the hands of the Government, he was so circumstanced as to have every expectation, after his father's death, of leading a happy and prosperous life. Married to a young and lovely wife, the bearer of an ancient name, the owner of a great estate, the father of two little boys, it was especially hard that, listening to the temptations of scoundrels, he should be hanged, like a common cutthroat or pickpocket, at the early age of twenty-eight.[7]

Unlike the majority of his confederates, Ambrose Rookewood, it should be noticed, had always been, without a break, a staunch and bigoted Roman Catholic, from his childhood upwards; and, in order to obtain a thorough religious education, in strict accordance with the tenets of his faith, he had been educated abroad. Ambrose Rookewood's mansion, Coldham Hall, still stands, and is remarkable for containing at least three secret chambers, which are reputed to have been used to conceal priests. In the curious chapel, Mass was undoubtedly said in the presence of Ambrose and his family. On joining the conspiracy, Rookewood moved, in order to be within closer reach of the abodes of Catesby, Tresham, Digby, Grant, and the Winters, from Suffolk into Warwickshire, where he rented Clopton Hall. This house, besides 'priest's holes,' had a little chapel hidden in the roof, where Mass was often said. [8]

- ↑ 'And soone after we tooke another unto us, Christopher Wright, having sworn him also, and taken the Sacrament for secrecie' (Guy Faukes's confession).

- ↑ Of this there is no proof beyond Coke's ipse dixit. He confessed, however, his intentions, and the design of the plotters, to Greenway.

- ↑ It is an extraordinary fact that so many of the plotters should have been engaged in the Essex rebellion. This suggests that Lord Essex was secretly supported by the Jesuits.

- ↑ Heir to the Earldom of Shrewsbury.

- ↑ Near Droitwich.

- ↑ Elizabeth's ingratitude to Edward Rookewood was base in the extreme. After being entertained by him at great expense, she sent him to prison, and ruined him with fines.

- ↑ Ambrose, nevertheless, was not the last conspirator of his ill-fated race, as his grandson, also named Ambrose, was hanged in 1696, for being concerned in a plot to kill or kidnap King William III.

- ↑ For an account of the houses (containing secret chambers) used by the conspirators, the reader cannot do better than refer to Mr. Allan Fea's superb book, Secret Chambers and Hiding-Places. (Mr. Fea is, however, in error when he states that Sir Everard Digby was captured at Holbeach.)