Admiral Phillip/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

For Phillip the sea-captain, the anxieties of a long voyage under unusual and trying circumstances were ended, and his weather-beaten ships safely anchored; for Phillip the Governor (not in its present quasi-ornamental interpretation, but what is signified by the word's real meaning), the work was now to begin. 'The commander over men; he to whose will our wills are to be subordinate and loyally surrender themselves, and find their welfare in doing so, may be reckoned the most important of Great Men.'

If Phillip, in his small way, so governed that his subjects did loyally surrender themselves, and found their welfare in so doing, then he may take rank with the 'most important of Great Men.' But as yet he had other things to consider than methods of governing—chief among them the site of the settlement—for Botany Bay, he found, would not do. The very appearance of the country must have been disheartening, for Botany Bay is about as unlovely a spot as can be imagined; and indeed the whole coast line of New South Wales, even at that season of the year—the middle of summer—presented a monotonously repellent and forbidding aspect to people whose eyes were used to the soft beauties of the scenery of their native land.

Phillip went expeditiously to work. There was no shifting of responsibilities upon the authorities; no waiting for instructions from the Home Office. He had to decide at once, at the very beginning of the business, where, after his eight months' voyage, he should land his thousand subjects. And no doubt he congratulated himself that he had taken care before he left England to have liberty to change the intended site of the settlement.

His first despatch, dated Sydney Cove, 15th May 1788, tells Lord Sydney his reasons for making the change. Almost as soon as the Supply had anchored, he began to examine Botany Bay, which, though an extensive expanse of water, afforded no shelter from easterly winds—the 'disaster' wind of the eastern Australian seaboard. Then, too, the water was shallow, for the most part, except near the entrance, and his seaman's eye was quick to note that ships would be exposed to a heavy sea when easterly weather set in. Creeks of fresh water were plentiful (until quite recently the greater part of the water supply of Sydney was derived from the Botany Bay swamps), but the lowlands were spongy and swampy, and Phillip did not see 'any situation to which there was not some very strong objection,' though there were spots whereon a small number of people might have been settled. Yet even the most eligible situation, he considered, would be unhealthy by reason of the swamps, and he decided to examine Port Jackson, fifteen miles to the northward. But so that no time should be lost, in case his search for a better harbour and site for a settlement should prove fruitless, he at once gave orders for a certain area of ground 'near Point Sutherland, to be cleared, and preparations made for landing under the direction of the Lieutenant-Governor.'

The story of his discovery of the site of the future settlement may well be left to himself:—'I went round' (from Botany Bay) 'with three boats, taking with me Captain Hunter and several officers, that by examining different parts of the port at the same time less time might be lost. We got into Port Jackson early in the afternoon, and had the satisfaction of finding the finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security, and of which a rough survey, made by Captain Hunter and the officers of the Sirius after the ships came round, may give your Lordship some idea. The different coves were examined with all possible expedition. I fixed on the one that had the best spring of water, and in which the ships can anchor so close to the shore that at a very small expence quays may be made at which the largest ships may unload. This cove, which I honoured with the name of Sydney, is about a quarter of a mile across at the entrance, and half a mile in length.'

Three days later he returned to Botany Bay, and immediately made preparations to leave. Ordering Hunter to follow him with the transports, he sailed in the Supply for Port Jackson on 25th January—seven days after he had first anchored in Botany Bay—and on the following evening all the transports were safely moored in Sydney Cove.

Whilst the ships were lying at Botany Bay, the Boussole and the Astrolabe, two French exploring ships commanded by the ill-fated La Pérouse, appeared and dropped anchor. Learning that La Pérouse was anxious to send letters to Europe by the returning transports, Phillip sent an officer over to him to receive the despatches. This meeting with La Pérouse was the last occasion on which the Frenchmen were seen, and the despatches sent by the French Admiral through the English exiles contained the last news the French received of their exploring expedition until forty years later, when the relics of the fortunate ships were discovered on the island of Vanikoro.

The task of clearing the ground and erecting storehouses was begun as soon as the ships arrived in Port Jackson—'a labour of which it will be hardly possible,' says Phillip, 'to give your Lordship a just idea.' Then troubles came thick and fast; yet he does not dilate upon the worry and incessant strain he must have undergone from the day he landed his people to the date of his letter to Lord Sydney, a period of sixteen weeks. Here is a long extract:—'The people were healthy when landed, but the scurvy has, for some time, appeared amongst them, and now rages in a most extraordinary manner. Only sixteen carpenters could be hired from the ships, and several of the convict carpenters were sick. It was now the middle of February; the rains began to fall very heavy, and pointed out the necessity of hutting the people; convicts were therefore appointed to assist the detachment in this work.

'February the 14th the Supply sailed for Norfolk Island, with Philip Gidley King, second lieutenant of His Majesty's ship Sirius, for the purpose of settling that island. He only carried with him a petty officer surgeon's mate, two marines, two men who understood the cultivation of flax, with nine men and six women convicts. … I beg leave to recommend him as an officer of merit, and whose perseverance in that or any other service may be depended upon. …

'Your Lordship will not be surprized that I have been under the necessity of assembling a Criminal Court. Six men were condemned to death. One, who was the head of the gang, was executed the same day; the others I reprieved. They are to be exiled from the settlement, and when the season permits I intend they shall be landed near the South Cape, where, by their forming connexions with the natives, some benefit may accrue to the public. These men had frequently robbed the stores and the other convicts. The one who suffered and two others were condemned for robbing the stores of provisions the very day they received a week's provisions, and at which time their allowance … was the same as the soldiers, spirits excepted; the others for robbing a tent, and for stealing provisions from other convicts.

'The great labour in clearing the ground will not permit more than eight acres to be sown this year with wheat and barley. At the same time the immense number of ants and field-mice will render our crops very uncertain. Part of the live stock brought from the Cape, small as it was, has been lost, and our resource in fish is also uncertain. Some days great quantities are caught, but never sufficient to save any part of the provisions; and at times fish are scarce.'

'The very small proportion of females makes the sending out an additional number absolutely necessary, for I am certain your Lordship will think that to send for women from the Islands, in our present situation, would answer no other purpose than that of bringing them to pine away in misery.

'Your Lordship will, I hope, excuse the confused manner in which I have in this letter given an account of what has past since I left the Cape of Good Hope. It has been written at different times, and my situation at present does not permit me to begin so long a letter again, the canvas house I am under being neither wind nor water proof.'

In reading these extracts, it should be remembered that all previous knowledge of Port Jackson is summed up in these words from Cook's Voyages: 'At this time (noon, 6th May 1770) we were between two and three miles distant from the land and abreast of a bay or harbour in which there appeared to be a good anchorage, and which I called Port Jackson.'

Phillip was not the man to waste words in his despatches, and so he says nothing of the interesting ceremony at the inauguration of the settlement. On this subject latter-day historians have not been so reticent, and one writer in a book published thirty-five years ago put an up-to-date speech into the mouth of the Governor, in which, among other things equally remarkable, he is made to discourse of the country's 'fertile plains, tempting only the slightest labours of the husbandman to produce in abundance the fairest and richest fruits; its interminable pastures, the future home of flocks and herds innumerable; its mineral wealth, already known to be so great as to promise that it may yet rival those treasures which fiction loves to describe. Enough for any nation, I say, would it be to enjoy those honours and those advantages, but others, not less advantageous, but perhaps more honourable, await the people of the state of which we are the founders.'

Collins, Tench, White, and the author of the semi-official publication, Phillip's Voyage, all supply full accounts of the ceremony, and young Southwell gives in one of his letters what appears to be a verbatim report of Phillip's speech:—

'On the 26th of January' (still observed as a public holiday in the colony), 'the day after the arrival of the ships from Botany Bay, the Union Jack was hoisted at the head of Sydney Cove, the marines saluted and fired three volleys, and the Governor, the centre of a little group of officers, proposed the toasts of "The King and the royal family," and "Success to the new colony."'

On the 7th February, everyone belonging to the settlement having been landed from the ships, the colonists to the number of 1030 were all assembled, the convicts seated in a half circle, the marines paraded in front of them, and the officers in a group in the centre. Then Collins, the Judge-Advocate, read the Governor's commission, the other officers' commissions, the Act establishing the colony and the rest of the formal documents, the marines fired three volleys, and silence was commanded.

Phillip stepped forward, and in a hearty, simple manner thanked the marines for their good conduct, and then turning towards the convicts, according to Southwell, he thus addressed them:—

'You have now been particularly informed of the nature of the laws by which you are to be governed, and also of the power with which I am invested to put them into full execution. There are amongst you, I am willing to believe, some who are not perfectly abandoned, and who, I hope and trust, will make the intended use of the great indulgence and lenity their humane country has offered; but at the same time there are many, I am sorry to add, by far the greater part, who are innate villains and people of the most abandoned principles. To punish these shall be my constant care, and in this duty I ever will be indefatigable, however distressing it may be to my feelings. Not to do so would be a piece of the most cruel injustice to those who, as being the most worthy, I have first named; for should I continue to pass by your enormity with an ill-judged and ill-bestowed lenity, the consequence would be, to preserve the peace and safety of the settlement, some of the more deserving of you must suffer with the rest, who might otherways have shown themselves orderly and useful members of our community. Therefore you have my sacred word of honour that whenever you commit a fault you shall be punished, and most severely. Lenity has been tried; to give it further trial would be vain. I am no stranger to the use you make of every indulgence. I speak of what comes under my particular observation; and again I add that a vigorous exercise of the law (whatever it may cost my feelings) shall follow closely upon the heels of every offender.'

After some other words tending to this effect, they had liberty to disperse, and the Governor then passed up and down through the ranks of the marines upon parade, and having been saluted by them with due honours, went, together with the principal officers, to partake of a cold repast that had been previously prepared in a marquee. During the whole ceremony, at intervals, the band played, and 'God Save the King' was performed after the commissions were read.

According to Phillip's Voyage, the Governor concluded his speech by particularly noticing 'the illegal intercourse between the sexes as an offence which encouraged a general profligacy of manners and was in several ways injurious to society.' To prevent this, he strongly recommended marriage, and promised 'every kind of countenance and assistance to those who by entering[1] into that state should manifest their willingness to conform to the laws of morality and religion.' He formally declared 'his earnest desire to promote the happiness of all who were under his government, and to render the settlement in New South Wales advantageous and honourable to his country.'

It is clear that Phillip had ample reason to complain of the conduct of the prisoners.

'Many of them,' says Collins, 'tried to desert to the French ships' (the Boussole and Astrolabe) 'before they left Botany Bay, and it was soon found that they secreted at least one-third of their working tools, and that any sort of labour was with difficulty procured from them. The want of proper overseers principally contributed to this. … Petty thefts among themselves began soon to be complained of. The sailors from the transports brought spirits on shore at night, though often punished for so doing, and drunkenness was the consequence.'

The first despatch of the Governor has already given some idea of the progress of the settlers for the first few weeks after they landed. Before that letter left for England in one of the returning transports, it was becoming apparent to Phillip that the colony would not be self-supporting for a long while to come.

Phillip kept a regular journal, sending a copy of it, brought up to date, by each transport as the ship left for England by way of China. In July he despatched a very long letter to Lord Sydney, and these extracts from it will be of interest:—

'Thus situated, your Lordship will excuse my observing a second time that a regular supply of provisions from England will be absolutely necessary for four or five years, as the crops for two years to come cannot be depended on for more than what will be necessary for seed. … I should hope that few convicts will be sent out this year or the next, unless they are artificers, and … I make no doubt but proper people will be sent to superintend them. The ships that bring out convicts should have at least the two years' provisions on board to land with them, for the putting the convicts on board some ships and the provisions that were to support them in others, as was done … much against my inclination, must have been fatal if the ship carrying the provisions had been lost.

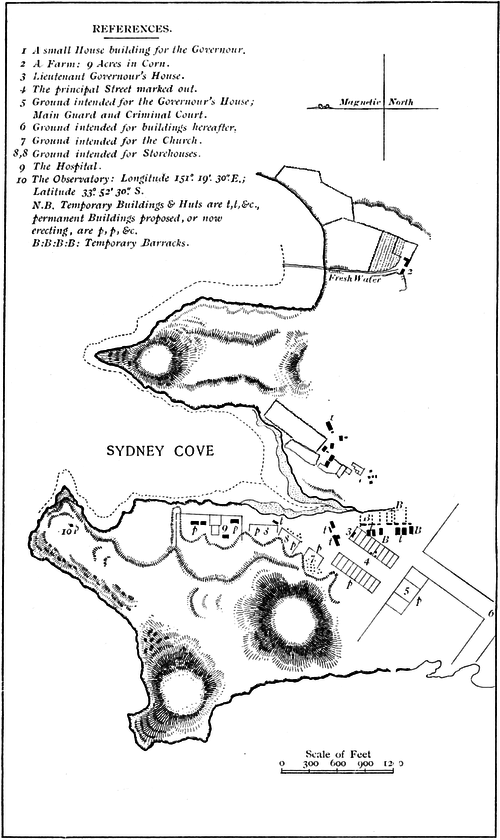

'I have the honour to enclose your Lordship the intended plan for the town.[2] The Lieutenant-Governor has already begun a small house, which forms one corner of the parade, and I am building a small cottage on the east side of the cove, where I shall remain for the present with part of the convicts and an officer's guard. The convicts on both sides are distributed in huts, which are built only for immediate shelter. On the point of land which forms the west side of the cove an Observatory is building, under the direction of Lieutenant Dawes,

Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, 1788

who is charged by the Board of Longitude with observing the expected comet. The temporary buildings are marked in black; those intended to remain, in red. We now make very good bricks, and the stone is good, but do not find either limestone or chalk. … The principal streets are placed so as to admit a free circulation of air, and are two hundred feet wide. …' Then follows a detailed account of the progress made so far in building operations generally.

'Of the convicts,' he writes, '36 men and 4 women died on the passage, 20 men and 8 women since landing—11 men and 1 woman absconded; 4 have been executed, and 3 killed by the natives. The number of convicts now employed in erecting the necessary buildings and cultivating the lands only amounts to 320—and the whole number of people victualled amounts to 966—consequently we have only the labour of a part to provide for the whole. …

'I could have wished to have given your Lordship a more pleasing account of our present situation; and am persuaded I shall have that satisfaction hereafter; nor do I doubt but that this country will prove the most valuable acquisition Great Britain ever made; at the same time no country offers less assistance to the first settlers than this does; nor do I think any country could be more disadvantageously placed with respect to support from the mother country, on which for a few years we must entirely depend.'

From a private letter of the same date to Under-Secretary Nepean, we may extract the following passages:—

'I am very sorry to say that not only a great part of the cloathing, particularly the women's, is very bad, but most of the axes, spades, and shovels the worst that ever were seen. The provision is as good. Of the seeds and corn sent from England, part has been destroyed by the weevil; the rest in very good order. …

'If fifty farmers were sent out with their families, they would do more in one year in rendering this colony independent of the mother country, as to provisions, than a thousand convicts. There is some clear land, which is intended to be cultivated, at some distance from the camp, and I intended to send out convicts for that purpose, under the direction of a person that was going to India in the Charlotte transport, but who remained to settle in this country, and has been brought up a farmer, but several of the convicts (three) having been lately killed by the natives, I am obliged to defer it untill a detachment can be made.'

Here is another complication, and a description of the climate:—

'The masters of the transports having left with the agents the bonds and whatever papers they received that related to the convicts, I have no account of the time for which the convicts are sentenced, or the dates of their convictions. Some of them, by their own account, have little more than a year to remain, and, I am told, will apply for permission to return to England, or to go to India, in such ships as may be willing to receive them. If lands are granted them, Government will be obliged to support them for two years; and it is more than probable that one-half of them, after that time is expired, will still want support. Until I receive instructions on this head, of course none will be permitted to leave the settlement; but if, when the time for which they are sentenced expires, the most abandoned and useless were permitted to go to China, in any ships that may stop here, it would be a great advantage to the settlement.

'The weather is now unsettled, and heavy rains fall frequently; but the climate is certainly a very fine one, but the nights are very cold, and I frequently find a difference of thirty-three degrees in my chamber between 8 o'clock in the morning and 2 o'clock in the afternoon, though the sun does not reach the thermometer, which is at the west end of my canvas house.'

Notwithstanding all his troubles, the Governor still kept a good heart, for he ends with a cheery declaration that neither patience nor perseverance, in the laborious task before him, will be wanting on his part. It will be seen in what follows how well this promise was fulfilled.