America's Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program/Part 1/Chapter 12

to the

Enactment

of the 1956

Federal-Aid Highway Act

Rapid Recovery of Motor Traffic to Prewar Levels

After the surrender of Japan, the American economy shifted from war to peace with remarkable speed. Huge wartime savings, some $44 billion, created an insatiable market for housing and for all kinds of goods, including new automobiles to replace the decrepit vehicles that had survived the war. Automobile production jumped from a mere 69,532 in 1945 to over 2.1 million in 1946, 3.5 million in 1947 and 3.9 million in 1948.[1]

Reflecting this vast increase in vehicle production, registrations increased 22 percent, from the wartime low of 30.6 million vehicles to 37.4 million vehicles in 1947. (In this period trucks increased by 34 percent.) With the end of rationing and emergency speed controls, highway travel reached its prewar peak in 1946 and began a steady climb of about 6 percent per year that was to continue for decades.[2]

The Nation’s highways were in poor shape to receive this traffic. Most of. the deficiencies disclosed in the 1941 survey of the strategic network still existed in 1946. Under wartime restrictions, the States could do little to remedy them, and, in fact, because of wide-spread operation of overloaded trucks and reduced maintenance, the State highway systems were in worse shape structurally after the war than before.

The Urban Traffic Problem

In and near the cities, hundreds of miles of highways were functionally obsolete because of narrow pavements, ribbon development and insufficient capacity. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, migration of the more affluent inhabitants to outlying suburban areas created expansive thinly spread residential communities surrounding the major cities. This movement to the suburbs, which began in the days of the steam and electric railroads, was greatly accelerated by the private automobile. As the street and highway networks expanded, more and more people found it convenient to live in the suburbs and drive to and from work, but the convenience decreased rapidly as the highways became congested with ever-increasing volumes of vehicles.

The city, county and State highway authorities tried to keep up with the traffic increase, first by widening streets and highways and then by providing special high-capacity roads such as parkways and expressways, commonly financed by bond issues.[N 1] These special facilities expanded the radius of suburban development and attracted so much more traffic that they too became seriously congested.

- ↑ In the prewar period, the outstanding examples of such deluxe facilities were the Westchester County Parkways and the Long Island State Parkway System. The latter, begun in 1925, by 1947 had expanded into a 158-mile network of commuter arteries tying western Long Island to downtown New York.[3] In the west, the Arroyo Seco Parkway between Los Angeles and Pasadena, opened in 1940, was a dramatic demonstration of what could be done to move large volumes of traffic to and from the suburbs.

With the postwar availability of VA housing and new automobiles, people began to move from the city to outlying suburban areas. Highway authorities tried to keep pace with the commuters, but the day was at hand for the rush-hour traffic jam.

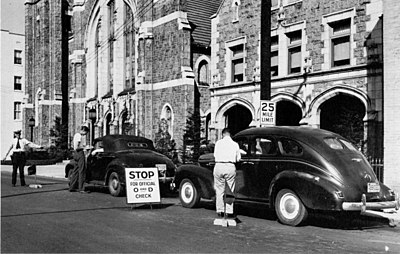

An “origin-and-destination” survey.

Before the war was over, many of the State highway departments became involved with the large cities and urban counties in the planning of costly schemes for expanding highway capacities. Most of the Federal aid provided by Congress for postwar planning went into urban highways.

Federal Aid for Urban Highways

In its early days, the Federal-aid program applied strictly to rural roads, “excluding every street and road in a place having a population, as shown by the latest available Federal census, of two thousand five hundred or more, . . .”[4] This exclusion was suspended in the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 and the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, and abolished altogether in the Hayden-Cartwright Act of 1934. Thereafter, the States enlarged their Federal-aid systems to include extensions of Federal-aid routes into and through municipalities and even new routes wholly within urban areas, but the main interest of the State highway departments was in the rural highway systems outside the cities.

Congress changed all this in 1944 by specifically earmarking $125 million annually for the first 3 post-war years for roads in urban areas. These funds were to be apportioned to the States in the ratio that their urban populations (cities of 5,000 or more inhabitants) bore to the national urban population. In the same Act, Congress established the National System of Interstate Highways and required that its routes should be selected by the States within the cities as well as between them. Thus, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 brought the State highway departments, and also the Public Roads Administration (PRA), actively into the field of city and regional transportation planning beside the city and county officials.[N 1]

- ↑ The Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) had pioneered in urban traffic studies in the Cook County Transportation Survey of 1924, the first comprehensive study of traffic in an urban region including a large city[5] and in the Cleveland Regional Area Traffic Survey of 1927. The latter was the first concerted study by all levels of government of the traffic problems of a single metropolitan region.[6]

Urban Traffic Studies

Before they could designate the urban Interstate System arteries with confidence, the planners needed to know a great deal more than they already knew about the movements of traffic within cities and between cities and their suburbs:

Traffic within an urban area is more complex than on rural roads. Traffic volumes are larger, and arteries are much more numerous. Parallel streets offer many alternate routes of travel, and it is not possible to tell from observing traffic volumes alone where the drivers really want to go. Drivers often travel considerable distances out of their way to use exceptionally attractive routes, or to avoid congested or unattractive routes. Examples of this have been noted in numerous cities and origin-and-destination surveys have shown that the facts were sometimes quite different from assumptions made by engineers with long familiarity with the local situation.[7]

The old techniques that had been developed in previous years during the cooperative State-BPE traffic surveys and the statewide highway planning surveys, such as driver interviews and postcard questionnaires, were too costly, too cumbersome or not sufficiently accurate. The planners needed a better method of estimating future traffic flows, and they found it in the “origin-and-destination survey,” a sampling technique developed in 1944 by the PRA with the help of the Bureau of the Census.[8] The origin-destination surveys were made by interviewing a sample of the urban population at their homes and obtaining from each family in the sample detailed information on the travel habits of its members. Samples varied from as small as 1 dwelling unit in 30 to as high as 1 in 3, but averaged about 1 in 10.

During 1944 and 1945 the State highway departments and local officials, with the help of the PRA, analyzed the needs of 30 large metropolitan areas and 135 cities of 50,000 or less population.

By providing the means to estimate the traffic volumes that will use any specific route, these studies serve to evaluate the merits of proposals advanced by different groups within an urban area, and to bring together the various local agencies in the support of a single plan. Availability of the facts often permits harmonizing the views of differing factions, each of whose proposals, in the absence of facts, is of necessity based on opinions.[9]

A Larger Share of the Highway Dollar for Non-Federal-Aid System Roads

As statewide traffic increased, so did gasoline tax revenues, and inevitably there was political pressure to distribute some of this revenue to the counties as State aid for their roads. In many States a considerable part of the State-collected road-user revenues was redistributed to the counties, and often in greater amounts than was generated within a specific county.[N 1]

As the State contributions increased, most counties reduced their own support for local roads (the revenues being derived mostly from property taxation) so that by 1947 local governments were carrying only about 40 percent of the cost of construction and maintenance where 20 years before they had carried over 80 percent.[11][N 2]

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and the Hayden-Cartwright Act of 1934 had provided emergency funds that could be spent on “secondary or feeder” roads off the Federal-aid system “to be agreed upon by the State highway departments and the Secretary of Agriculture.” Although not required by the legislation, the Secretary, through the Bureau of Public Roads, insisted that these funds be spent on connected road systems in each State as a condition for his agreement.[12] The States then, in selecting systems, for the most part, selected the roads carrying the most traffic, but not necessarily those most desired by the local officials. These systems totaled about 138,500 miles, and on them about $245 million of emergency relief and regular Federal-aid funds were spent by the States in the period from 1934 to 1943.

Nevertheless, there was widespread dissatisfaction with the county roads among rural residents, accompanied by an unwillingness to increase taxes to improve them. This feeling led to increased political pressure on the State governments for a larger share of road-user taxes and also pressure on Congress for direct Federal aid to the counties. In 1943 Senator A. T. Stewart of Tennessee introduced a bill to set up a Rural Local Roads Administration with $1.1 billion in Federal funds to be distributed among the counties without going through the State highway departments.[13] This bill never emerged from committee, but its supporters were able to include a very generous measure of assistance for local rural roads in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944.

The Federal-Aid Secondary Road System

The 1944 Act authorized the appropriation of $150 million in each of the first 3 postwar years for projects on the “principal secondary and feeder roads” but required that the funds be spent on “a system of such roads selected by the State highway departments in cooperation with the county supervisors, county commissioners, or other appropriate local road officials, and the Commissioner of Public Roads.” The money was to be apportioned to the States one-third according to State area, one-third according to rural population and one-third according to the mileage of rural mail delivery and star routes, and the Federal share of any project was limited to 50 percent.

Congress imposed no mileage or percentage limits on the secondary system, and it soon became apparent to the State highway departments that their previously selected secondary systems were not nearly large enough to satisfy the local authorities. However, the PRA arbitrarily set guidelines for selecting routes which had the effect of limiting the mileage. First, these guidelines required that the State Federal-Aid Primary System and the selected Secondary System be integrated to form continuous networks. Second, the PRA limited the mileage it would approve to a system not larger than could be constructed and maintained with the funds that “might reasonably be expected to be provided” according to past performance in the area.[N 3]

The system approved by the Commissioner of Public Roads in June 1946 totaled 217,073 miles, but this was just a beginning, as tens of thousands of miles of additional routes were then still under review. According to the PRA, “No route is approved without first assessing its importance by reference to the records made in the planning surveys showing locations of farms, schools, churches, and business establishments, type of existing road improvement, general population distribution, and the amount of traffic.”[14] By June 1947 the Secondary System had increased to 350,809 miles and by 1948 to 377,622 miles. It reached 502,676 miles in 1955.

- ↑ In 1944 it was estimated that nationally, about 61 percent of road-user revenues was going to the State highway departments, about 26 percent to the counties and cities for their roads and streets, and the rest to nonhighway uses.[10]

- ↑ In Delaware, North Carolina, West Virginia and Virginia (except for two counties), the highway departments are responsible for all roads outside of municipalities because the local governments succeeded in shifting the entire road burden to the State.

- ↑ Planning for the Federal-Aid Secondary Systems had the beneficial effect of forcing the States to reexamine and update their Primary Systems. Nationwide, about 40 percent of the Federal-aid secondary routes were already under State control or were immediately taken over by the States. The rest remained under local control.

The States Select Interstate System Routes

By the 1944 Act, Congress had limited the National System of Interstate Highways to 40,000 miles and had also provided that the routes should be selected by joint action of the State highway departments of each State and the adjoining States. All routes so selected were automatically to become part of the Federal-Aid Primary System without regard to previous mileage limits on that System.[N 1]

In February 1945 the PEA requested each State to submit recommendations for the Interstate System routes within its boundaries. When these recommendations were all in, they totaled 45,070 miles—considerably over the legal limit and far above the 33,920 miles recommended by the Interregional Highway Committee.[16] Two thousand miles were circum- ferential or distributing routes around the large cities. The PRA decided to defer consideration of these to a later date and concentrate on getting the States to agree on the main routes between the cities.

After weeding out the routes with the weakest justifications and adding a small mileage requested by the War Department, the PRA came up with a total of 37,324 miles for the main routes. In March 1946 the PRA sent each of the States a map showing this tentative integrated system and asked for their concurrence. The first State to concur was Nebraska, and by June 1946 acceptances had been received from 37 States.[17]

It required a year for the PRA and the remaining 11 States to iron out their differences, but agreement was finally reached on a 37,681-mile System, including 2,882 miles of urban thoroughfares. Some 2,319 miles were reserved for urban circumferential and distributing routes, to be selected later. The Federal Works Administrator approved this System on August 2, 1947.[18]

Interstate System Standards Adopted

While the States were selecting the Interstate routes, the PRA asked the American Association of State Highway Officials to propose standards to control the location and design of the Interstate highways. “There was no thought of requiring that every mile of the system be built according to a rigid pattern but it was believed essential that there be a high degree of uniformity where conditions as to traffic, population density, topography, and other factors are similar.”[19]

The projected routes of the Interstate System as approved by the Federal Works Administrator, 1947.

AASHO’s Committee on Planning and Design Policies had been formed in 1937 to review and evaluate the immense amount of research and operational information on highways that had accumulated since the 1920’s.[N 2] Between 1938 and 1944 the Committee summarized the existing knowledge of geometric design and good design practice in seven “Policies” which were adopted by the Association and became, in effect, the national design policies for highways. Because of this prior work, the Committee was able to recommend standards for the Interstate System by June 1945, and these were adopted by AASHO and approved by the Federal Works Administrator in August 1945.[N 3]

Of necessity, the Interstate standards were a compromise. A few States thought they were inadequate, pointing to the provision permitting three-lane highways for traffic volumes intermediate between those requiring a two-lane highway and those requiring a four-lane divided highway. Some criticized the weak provisions permitting grade crossings with railroads and other highways for low-traffic sections of the Interstate System. In these respects, the standards fell far below those for existing parkways and turnpikes which had been held up to the public by many people as the ideal for the Interstate System.

To get wide acceptance of the standards, the Committee equivocated on other elements of design by setting up “minimum” and “desirable” levels of de- sign. Thus, for level country, a State could elect to use either a 60- or 70-mile per hour design speed. For right-of-way, the “desirable” width for divided highways was 250 feet, but in a pinch the State could get by with the “minimum” of 150 feet.

- ↑ The Federal-aid system (later the Primary System) was limited to 7 percent of each State’s total highway mileage by the 1921 Act. Congress, in 1932, allowed 1 percent increments to be added as a State improved 90 percent of the entire Federal-aid system in that State.[15]

- ↑ Thomas H. MacDonald was chairman of this powerful committee from its inception until 1944. The Committee’s working staff of design experts was supplied by the BPR (and PRA) and functioned under Joseph Barnett, who was also secretary of the Committee.

- ↑ When the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act specifically called for adoption of uniform design standards for the Interstate System, these earlier standards were the basis for the new standards, permitting completion of the work in 2 to 3 months.

The lack of access control prevented free-flowing movement on this four-lane, undivided bypass of U.S. 101 in California.

Control of Access Recommended but Not Required for Interstate System

The most important deficiency in the standards concerned a matter over which AASHO had no control and little influence with the States. This was the control of access to the highway from abutting property. Two decades of experience had shown that new highways invariably attracted ribbon development by commercial enterprises catering to the traffic on the highway. Movements to and from these businesses disrupted the traffic stream on the highway and greatly increased accidents. Eventually, the ability of the highway to carry traffic was reduced far below its original capacity by the roadside activity. At the same time the cost of future widening was made prohibitive. Gradually, highway administrators began to realize that the only way to protect the capacity of the highway was to deny or restrict access to the road from the adjacent private property. This growing realization ran counter to the most deeply ingrained traditions of English common law and also most American statute law, which granted to abutters the very rights highway administrators now sought to take away.

The Bronx Kiver Parkway Commission acquired a broad expanse of parkland along each side of the parkway road. This practice effectively controlled access to the road while avoiding the question of the loss of access rights to abutting property owners. However, there was some doubt as to whether this was really sufficient, and the Westchester County Parkway Commission made it their practice to purchase access rights and specifically mention them in the deeds.[20] The Pennsylvania Legislature in the act creating the Turnpike Commission gave the Commission the power to acquire access rights, by eminent domain, if necessary. However, very few State legislatures conferred such rights on their highway commissions. By 1945 only 17 States had laws permitting the control of access to State highways.

The Committee on Planning and Design Policies skirted this ticklish question by saying,

Where State laws permit, control of access shall be obtained on all new locations and on all old locations wherever economically possible. . . In those States which do not have legal permission to acquire control of access, additional right-of-way should be obtained adequate for the building of frontage roads connecting with controlled access points, if and when necessary.[21]

Slow Start of the Postwar Highway Program

When the war ended, the States were well prepared with plans for the largest highway program in history. On the shelf ready to go were plans for $590 million worth of road improvements, and plans for another $2.5 billion worth of work were well advanced. A total of about $624 million in Federal aid was available from prewar and postwar authorizations, and most of the States had ample matching funds saved up during the war/[22] Most highway departments anticipated some difficulty in obtaining trained engineers and building contractors, but this did not seem at first to be a great obstacle.

On October 2, 1945, Congress, by concurrent resolution, declared that the war emergency had been relieved to such an extent that the postwar road program authorized by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 could proceed. About the same time most of the wartime restrictions on road building were lifted. Eager to launch the postwar program as soon as possible, and urged on by the PEA, the State highway departments advertised hundreds of jobs during the winter of 1945–46, some of them for very large bridges or urban expressways.

The result was, in some respects, a repetition of the 1920 experience. During World War II the inflation in road construction prices had been held to about 6 percent per year by price controls, and after 1943, by scarcity of work. A number of contractors had gone out of business, and those remaining were short of serviceable equipment and labor. The increased offerings of the State highway departments in 1945 and 1946 quickly saturated the available capacity of the construction industry and prices began to rise. At the same time materials scarcities developed, particularly in steel and lumber, which were in great demand for housing. The general uncertainty in prices and supplies resulted in higher bids, and by the end of 1946, the prices of highway structures had risen 24 percent over the 1945 level. Concrete pavement was up 12 percent.[23]

The States began rejecting the low bids that were far above preliminary estimates in an attempt to stem the tide of advancing prices. By the end of fiscal year 1946, only 1,958 contracts for $298 million of construction had been awarded—less than a third of earlier expectations. Twenty-two percent of all low bids received had been rejected as too high.[24] In some States, rejections ran as high as 30 percent of the low bids received.

This policy of rejecting low bids was ineffective, largely because the country was in the early stages of a building boom fueled not only by the State road programs, but also by large city expressway schemes, a huge increase in housing, and construction for industrial reconversion.

In August 1946, the Director of War Mobilization and Reconversion restricted highway construction to ease competition with the housing program for scarce materials. This restriction was lifted in October except for structural steel, but it had its effect along with rising prices in reducing State contract awards. Prices in 1947 reached a level 45 percent above 1945 prices and nearly double the prewar level. Unwilling to admit that prices had risen permanently to a new plateau, the States rejected 18 percent of all low bids received in fiscal year 1947.

Despite these difficulties, the States made a much better showing in 1947 than 1946, awarding contracts for 47,163 miles of road estimated to cost $817.7 million. Most of these were for rural primary or rural secondary roads and for simple projects such as repaving which did not require right-of-way or expensive plans.

The situation was quite different in the urban areas where most of the projects were arterial street widenings, new expressways or large bridges. Some of these schemes were very large indeed and required the acquisition and demolition of hundreds of buildings and the relocation of many families at a time when it was almost impossible to find other housing for them.

The State highway departments, usually in cooperation with the large cities or urban counties, started over a score of expensive expressway projects in 1947, each expected to cost in the millions. New York began clearing the way for the $34 million Cross-Bronx Expressway and the equally expensive Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Massachusetts began the Northern Circumferential Highway around the Boston metropolitan area, while Michigan launched the John C. Lodge Expressway and the Edsel Ford Expressway in Detroit, each expected to cost over $6 million per mile. In Chicago work began on the Congress Street Expressway, an eight-lane depressed freeway designed to accommodate 4,000 vehicles per hour in each direction, and estimated to cost $69 million. Expressways in Denver, Dallas, Fort Worth, Los Angeles, Oakland, Jacksonville, Miami, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Pittsburgh added to the huge total.

The shortages of contractors, labor, materials and equipment persisted through 1947, 1948, and into 1949. In addition, a severe shortage of highway engineers developed in 1946 and became worse as the highway departments expanded their programs. Most States had failed to raise their pay scales to keep in step with the inflation, and as a result, many engineers did not return to State service after the war or left for other employment in industry.

The Bronx River Parkway with controlled access and extensive parkland along each side.

Struggling against these handicaps and the continuing high prices, the States were able to obligate only 36 percent of their Federal-aid authorizations in fiscal year 1946, 62 percent in 1947, and 79 percent in 1948. It was necessary for Congress to extend the availability of the postwar authorizations by 1 year, and the unused backlog was so large that Congress made no authorization for fiscal year 1949 and reduced the authorizations for 1950 and 1951.

The Local Rural Road Problem

Although slow, there was improvement, and in 1949 the annual mileage of completed roads had reached the 1937 level of 21,000 miles, including about 14,000 miles of farm-to-market roads. But this did not satisfy the extreme rural road advocates.

The dissatisfaction in the counties found expression in two bills before Congress which would set up a Rural Roads Division in the Public Roads Administration with authority to dispense $100 to $200 million annually to the counties and local political subdivisions without going through the State highway departments.[25] There was also some rural sentiment for doing away with all system restrictions on rural roads so that their benefits could be more widely distributed among the rural population.

In testifying before the Senate Subcommittee on Roads on these bills, Commissioner MacDonald asserted that the proposed legislation would entail a “vast amount of costly supervision” on the part of the PRA to insure that the aided roads received proper maintenance. Rural roads, he said, were necessarily of light construction and required efficient and continuous maintenance to preserve their integrity. Past experience had shown that maintenance was the very aspect of road management in which the counties were weakest. Approval of the bills, according to MacDonald, would greatly dilute and weaken the fundamentally sound rural road program already in operation.[26] In May 1949, the Subcommittee requested Commissioner MacDonald to make a study of the rural road problem and report back to the Subcommittee by January 1950.

This rural road was widened but is still too narrow for 1953 traffic.

The PRA’s study, made with the help of the Board of County Consultants[N 1] and the State highway departments, did little to assuage the feelings of the extreme ruralists. The survey disclosed that of the 2.5 million miles of local roads in the United States in 1949, 323,000 miles were already on the Federal-Aid Secondary System. Another 100,000 miles carrying at least 100 vehicles per day could and should be transferred to the Federal-Aid Secondary System.[27] Another 400,000 miles was described as “wholly nonessential.” To bring the remaining 1.8 million miles up to acceptable standards and provide adequate main- tenance over a 20-year period would cost the local governments about $894 million per year. Since the local units were already spending $835 million per year on roads, the PEA concluded “It is apparent that a relatively small addition, with efficient management, applied to a planned program would be sufficient to accomplish the satisfactory improvement of local roads in a period of 20 years.”[28]

The report concluded that what local roads needed was not so much more money as improved administration. Federal cooperation and participation, the PRA thought, could best be achieved through coordination at the State level.

- ↑ In 1946 the Federal Works Administrator appointed a Board of County Consultants consisting of 10 county officials from the PRA’s 10 geographical administrative areas to advise the PRA on the secondary road program.

BPR “Driver Behavior” studies to measure speed, spacing, and lateral vehicle placement on the road, 1945.

Highway Needs Versus Financial Resources

In the early 1920’s some economists and even engineers predicted that the market for motor cars would become saturated. As the number of motor vehicles stabilized, road mileage and the need for road improvement would also stabilize. Eventually, the highway system would reach a state of “maturity” at which time there would be a diminishing need for capital expenditures, and most of the highway revenues would be used for maintenance.

This prediction was never realized. Instead, as national income increased, the automobile market expanded even more. The manufacturers were able to spend large sums on research, and they greatly improved the performance and reliability of motor vehicles. After World War I, motor trucks, which previously had operated only in cities, took to the highways and rapidly increased in numbers, size and speed.

As already noted, the highway administrators responded to this ever-increasing and continually changing vehicle population first, by upgrading the old wagon roads, and then by building improved new roads tailored to the motor vehicle. Finally, they invented new types of roads such as parkways and expressways to move huge volumes of traffic at high speeds. As the roads improved, the annual usage per vehicle increased, so that highway traffic built up faster than vehicle registrations in a self-reinforcing spiral. The highway system never reached maturity. The need for capital expenditures did not diminish, but increased enormously.

By the middle 1940’s, most States had accepted as a virtual certainty that their road systems would never be completed. They realized that they would have to plan highway improvements far into the future and establish a policy that would recognize future needs and provide for them:

Establishment of a highway policy that will result in adequate highway service in the future requires determination of the proper size and cost of systems of the different classes of highways needed. There must be an equitable plan for distribution of costs among highway users and general taxpayers, allocation of authority and financial responsibility among levels of government, and regulation of highway use to protect users and to obtain maximum service. Each element is so interrelated with others that complete facts on present conditions and most up-to-date results of transportation research are essential to develop an over-all analysis of highway needs to serve the interests of all in an equitable manner.[29]

In 1947, the California Legislature created a joint fact-finding committee from both houses to study the highway needs of the State “and to recommend a policy and means of putting that policy into action.”[30] The Michigan Good Roads Federation undertook a similar statewide needs analysis. Other States followed, and by 1950, 13 had published needs reports, and others were working on the complex studies for such reports.

The legislative and other fact-finding committees depended on their State highway departments, assisted by the BPR, to supply the factual information for their studies. Most of this factual material came from the tremendous bank of economic and traffic data assembled by the statewide planning surveys begun in the middle 1930’s. There was also a large amount of research information on driver behavior and the vehicle-carrying capacity of urban streets and rural roads that had been assembled before and after the war by the BPR, the States and the Highway Research Board’s Committee on Highway Capacity.

The compilation of future needs was simple in principle, but laborious in practice. First, the analysts had to forecast the traffic that might be expected in a future year and then assign the future traffic to the various roads in the several systems. Then, knowing the present condition of these roads and the desirable standards to handle the forecasted traffic, they could compile a list of “deficiencies.” Finally, they would compute the future cost of the construction needed to overcome these deficiencies. The sum of these costs was the estimate of needs for the particular year studied.

These predictions of future needs were necessarily painted with a broad brush. First, they depended on the continuation of past population, economic, vehicle registration, and traffic trends. And then there was considerable difference of opinion among the States as to what the standards should be to accommodate the future traffic. Nevertheless, there was a broad general agreement that the past trends would continue or even be exceeded and that the AASHO standards would be adequate or at least tolerable. The needs estimates were widely accepted as being well within the accuracy required for long-range financial plans and also for arousing popular support for the increased taxes and highway imposts that would be required to realize those plans.

It is safe to say that most of the State legislatures were astounded and dismayed by the size of the backlog of needs as shown by the needs studies. The California legislative committee found that it would cost $1.7 billion over a 10-year period to bring the State’s roads up to a reasonable standard. The cost in Washington was estimated at $509 million and in Oregon at $468 million.[31] The Michigan committee found needs that would cost $1.75 billion to remedy.[32] Connecticut, one of the smallest States in area, found needs exceeding $400 million, and in Massachusetts the needs exceeded $700 million.[33]

In 1950 AASHO made its own needs study and asserted that what was needed nationally to catch up with highway needs was a $4 billion annual program for 15 years ($1 billion for maintenance, $2.5 billion for construction and $500 million for interest, amortization and administration).[34] About the same time the Congressional Joint Committee on the Economic Report set the immediate national road needs at $41 billion.[35]

The reaction to the disclosure of these massive needs varied from State to State. The California Legislature immediately increased the gasoline tax by 1½ cents per gallon and radically amended the highway laws to speed up right-of-way acquisition and permit acquisition of land in advance of actual need to forestall speculative increases in land prices. Michigan raised its 3-cent gasoline tax to 5 cents per gallon and added 2 cents to the diesel fuel tax which, along with a hefty increase in the truck weight tax, raised an additional $135 million annually.[36] Other States looked to Congress to make up the difference between what they needed and what they could raise without pain with their current tax policies. Still others thought the solution was to get the Federal Government to withdraw from the taxing of fuel so that the States, without lowering the total tax, could use the Federal 2 cents per gallon for their own needs.

But most States decided on some form of credit financing to close at least a part of the gap. The Massachusetts Legislature authorized a $100 million bond issue backed by road-user revenues to improve the main highways and began looking into toll financing for some highways.[37] By a two-to-one vote, the voters of North Carolina approved a $200 million bond issue for rural roads. The bonds, backed by the faith and credit of the State, sold to yield an effective interest rate of only 1.52 percent.[38][N 1]

- ↑ By comparison North Carolina sold its road bonds in 1920 to produce an effective interest rate of 5 percent.

Traffic was concentrated around the cities, but the need to upgrade rural roads also demanded that limited funds be spread across the State, resulting in pavement widening projects such as this.

In New York, Governor Thomas E. Dewey, despairing of ever completing the Thruway System from diversion-depleted current revenues, authorized a study of revenue bond financing backed by tolls. When this study showed that tolls alone would not carry the project, the Legislature created the New York Thruway Authority and empowered it to sell $500 million in bonds backed by the State’s credit.[39]

Some State legislatures decided to wring as much as possible of the needed revenue from road users in the form of tolls on the theory that “every dollar that can be obtained from private sources to extend existing toll highways will mean a dollar of regular highway income released to match federal aid for highway building in some other part of the state.”[40] Other States, notably New Jersey, switched from pay-as-you-go financing to revenue bonds backed by tolls to build their most expensive and heavily traveled arteries. Between 1950 and 1954, the legislatures of 19 States created independent toll road authorities or authorized their State highway departments to build toll roads.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1950 permitted the States to borrow funds in the bond market against future Federal-aid apportionments. However, this authority did not make any new money available to the States or enhance their credit or change their own constitutional debt limits; and further, Congress carefully disclaimed any obligation to provide the future Federal-aid funds that might be used to redeem the bonds. Consequently, only a few States availed themselves of the privilege, and these for comparatively small amounts.

The Financial Dilemma of the State Highway Departments

The prices bid for highway construction peaked in late 1948 and then stabilized at about twice the prewar level. Highway maintenance costs also doubled because of the war and postwar inflation. This put the State highway departments in a double price squeeze at a time when highway traffic, and particularly truck traffic, was increasing alarmingly.[N 1] As the States put increasingly more of their income into maintenance, the money left for new construction, including Federal-aid matching, became less. The purchasing power of this remainder was only half that of the prewar period, yet the increased traffic demanded much heavier, wider and costlier roads than the prewar models.

Traffic growth was not uniform but was concentrated most heavily in the industrial States and, to a large extent, on a very small mileage near and between the large cities. Yet it was politically impossible for the highway departments to concentrate their funds on this small mileage. Their programs were designed to distribute highway work rather evenly over their States, and in a situation where all roads needed some improvement, it was not possible to deny some areas in order to build a few miles of costly superhighways near the cities.

Practically all of the States agreed that the most troublesome congestion was on the selected Interstate System routes. These had long been the most important traffic arteries and were now the oldest and most obsolete. Most of the highway departments made a determined effort to upgrade these old roads, and through fiscal year 1948 they channeled about 22 percent of their postwar primary and urban Federal aid and matching money, amounting to $384 million, into interstate projects. These totaled over 2,000 miles, including 800 bridges and grade separations, but this was a mere drop in the bucket compared to the obvious needs.

- ↑ In the 4 years from 1947 to 1950, registrations of privately owned vehicles increased by 11.2 million units—to a total of 48.60 million.[41] Annual vehicle miles of travel by passenger automobiles increased by 21 percent and by trucks 37 percent. In 1950, about 48 percent of the travel was in urban places, the rest on the rural roads.[42]

Congress Orders Reevaluation of Defense Highway Needs

As the States struggled to keep up with continual traffic increases, Western Europe was approaching economic collapse, and relations with the Soviet Union were deteriorating to a state of “cold war.” In 1947 Congress acted to provide massive military and economic aid for Turkey and Greece to help them resist Communist aggression. In April 1948 Congress approved the $17 billion Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe. In June 1948 the Soviets blockaded Berlin, and the United States responded with a massive air- lift to break the blockade.

In the tense atmosphere of these events, Congress became more conscious of the growing inadequacy of the country’s highways, and particularly the Interstate System to sustain a possible remobilization. It added a provision to the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1948 requiring the Commissioner of Public Roads to study the needs or potential needs of the Interstate System for national defense in cooperation with the Secretary of Defense, the State highway departments and the National Security Resources Board and report back to Congress not later than April 1, 1949.

The study began with a detailed inventory which disclosed an amazing diversity of geometric standards, widths and types of pavements, and dimensions and strengths of bridges among the 37,800 miles of existing roads in the System. The average age of the road surfaces was 12 years and 13 percent were more than 20 years old and nearing the end of their useful lives. In the rural sections, 6,000 miles had surfaces less than 20 feet wide and only 4,147 miles had more than two lanes. On 6,273 miles, the shoulders were less than 4 feet wide. There were 1,262 grade crossings with main line railroads and another 785 with branch lines and spur tracks. Of the 12,048 bridges on the System, only 677 were found to be below AASHO’s H 15 capacity, but there were many more of inadequate width, including 52 one-way bridges less than 18 feet wide. Of the existing bridges, 1,245, aggregating 29 miles in length, were of wooden construction.[43]

The PRA and the States measured the traffic using each section of the System and estimated the cost of upgrading each section to handle this traffic according to the standards proposed by AASHO for Interstate highways. They found that many sections would have to be completely relocated to meet the design speed, sight distance and gradient requirements and that the relocations would shorten the total length of the system by about 641 miles. All together, the investigators found that it would take an investment of $11.3 billion at 1948 prices to bring the Interstate System up to an acceptable standard to handle 1948 traffic. To meet this need in a 20-year period would require an investment of at least $500 million per year, according to the PRA’s report.

However, the report stated that the needs of the national defense would require a “substantially more rapid improvement,” and it pointed out that tremendous benefits to the civilian economy would flow from a faster rate of modernization. Rather than stretch out the work over 20 years, the PRA suggested credit financing with appropriations sufficient to amortize the bonds in 20 years. To this end, the report recommended that Congress consider permitting the States to borrow capital now to complete their sections of the Interstate System and use their future Federal-aid apportionments to repay the borrowings. To further promote rapid completion, the report suggested that Congress increase the Federal share of the cost of Interstate projects and also earmark funds specifically for the Interstate System. These earmarked funds should be apportioned so that the improvement of the System would proceed at about the same rate in all the States.[44]

In March 1950 Representative William M. Whittington of Mississippi introduced a bill to increase Federal aid for fiscal years 1952 and 1953 to $570 million per year, of which $70 million would be earmarked for the Interstate System, to be matched 75 percent Federal to 25 percent State. Whittington’s bill would also increase Federal participation in right-of-way costs to 50 percent and permit the States to use future Interstate apportionments to repay loans incurred to finance Interstate projects. This bill had the support of AASHO, except that AASHO had asked for $210 million for the Interstate instead of the paltry $70 million.[45]

Not all the State highway people were behind AASHO in this support. Led by the influential chief engineer of the Pennsylvania State highway department, the Association of Highway Officials of the North Atlantic States (AHONAS) passed a resolution opposing any further increase in Federal aid to the States, any further earmarking of funds for particular Federal-aid systems and any increase in the Federal share of projects. Increase in the Federal share would, AHONAS asserted, lead inevitably to more Federal control and intervention in State affairs.[46]

Other bills in the 2d session of the 81st Congress would have boosted Federal aid to $870 million annually with $100 million going directly to counties and townships. In the end, despite the continued unsettled conditions in Europe and the outbreak of war in Korea in June 1950, Congress left the road program substantially unchanged except for an increase of $50 million to restore the 1946–48 level of $500 million per year. There was no increase in the Federal matching share or any earmarking of funds for the Interstate System. The only important changes were raising Federal participation in right-of-way costs to 50 percent and the granting of permission for the States to use future Federal-aid apportionments to retire the principal of bonds issued to finance improvements on the Primary System, including the Interstate System.

Nearly 2 years passed before Congress took any further action on the PRA recommendations. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952 increased Federal support for the Primary and Secondary Systems to $550 million each for fiscal years 1954 and 1955 and also authorized $25 million for each of these years for the Interstate System. This token amount was to be apportioned according to the original Federal-aid formula and matched 50-50 by State funds.

Two years later in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954, Congress increased the whole Federal-aid program to $875 million per year, earmarking $175 million in fiscal years 1956 and 1957 for the Interstate System and increasing the Federal share to 60 percent on Interstate projects.

The reluctance of Congress to provide adequate funding for the Interstate System can be explained in part by a rising sentiment against the principle of Federal aid, and voiced by the 1953 Governors Conference which recommended that there be no further increases in aid, and that the Federal Government withdraw from the taxation of motor fuel.[47] However, the best excuse for congressional inaction was a strong indication from a number of States that they were well on the way to removing their worst traffic-bottlenecks by building roads without Federal assistance.

The Second Toll Road Era

The Pennsylvania Turnpike operated at a loss during the war years despite increased traffic. In 1944, 1.04 million vehicles used the turnpike and paid $1.78 million in tolls, yet the Authority lost $500,000 and had to draw on the reserve built up in 1940, 1941 and 1942.[48]

After the war, traffic increased rapidly, and this, with increased toll rates, quickly restored profitable operation. By 1948 the turnpike’s net operating revenue was $5.6 million per year. With the financial security of its original investment assured, the Pennsylvania Legislature authorized the Turnpike Commission to extend the turnpike 100 miles east to Philadelphia at an estimated construction cost of $75 million and 60 miles west to the Ohio State line for about $55 million.[49] The Commission had no trouble selling its bonds to eager investors.

Meanwhile Maine was pushing plans for a toll road to be built a few miles inland from U.S. Route 1 between the New Hampshire border and Portland. This road was expected to attract most of the summer traffic bound from New York and New England to the Maine resorts and thus take some of the pressure off congested Route 1. The Legislature thought this traffic would not mind paying a small toll to avoid the congestion on the old road.

As soon as wartime restrictions were lifted, the Maine Turnpike Authority sold $15 million of revenue bonds to finance the 47-mile road and began construction. Although the bonds were secured only by the future earnings of the turnpike, they sold readily at a net interest rate of only 2.64 percent. When the turnpike was opened in 1947, traffic exceeded estimates, and after some initial difficulties, the road operated in the black on a toll of about 1½ cents per mile.[50]

Building the New Jersey Turnpike.

With the completion by Massachusetts of a free expressway to the New Hampshire line and the opening of the Maine Turnpike, traffic congestion became intolerable on New Hampshire’s 15-mile portion of U.S. Route 1. Unable to obtain an increase in the gas tax from the Legislature to finance major improvements for the old winding road, the Highway Commission asked for authority to build a toll road financed by State bonds. The bonds, backed by the faith and credit of the State, sold for a net interest rate of only 1.58 percent. The toll road, built in only 1 year, opened to traffic in 1950 and was enormously profitable from the outset—so much so that the Legislature decided to build two more toll roads in other parts of the State.

In 1945 the New Jersey Legislature authorized a system of free expressways and parkways to relieve congestion in the densely settled New York–Philadelphia corridor. The system was started in 1946, but in a few years it became evident that highway revenues were insufficient to complete the system in any reasonable time. The Legislature then set up the New Jersey Turnpike Authority in 1949 to build the principal artery between the George Washington Bridge and the Delaware River, a distance of 117 miles. By-passing the New York bond houses, the Authority sold its revenue bonds to a consortium of 53 insurance companies in February 1950. It then embarked on a round-the-clock construction program that finished the $285 million toll road in less than 3 years.

From the opening of the first section in 1952, the turnpike was a resounding success and by 1953 was returning six times the operating expenses for a net operating revenue of $18.2 million per year. Traffic was 22 million vehicles during 1953 of which only about 12 percent were trucks and buses.

In 1947 the New York Legislature authorized Westchester County to collect a 10-cent toll on the Hutchinson River and Sawmill River Parkways provided the county reimbursed the Federal Government for the $2.15 million of Federal-aid funds spent on these parkways.[N 1]

The Toll Road Bandwagon Begins to Roll

The Pennsylvania, Maine, New Hampshire and New Jersey Turnpikes showed rather conclusively that the public was impatient with obsolete, congested highways and was willing to pay handsomely for modern freeways.[N 2] Other States, equally short of capital funds, began to consider credit financing schemes backed by tolls. Oklahoma in 1953 completed the 88-mile Turner Turnpike between Oklahoma City and Tulsa. New York, which had started its thruway as a free expressway, switched to toll financing in 1954 to accelerate construction. And West Virginia completed a 2-lane toll road from Charleston to Princeton in 1954. Colorado built the 17-mile Denver-Boulder Turnpike in 1952.

- ↑ The Hayden-Cartwright Act of 1934 authorized the expenditure of Federal-aid funds on “such main parkways as may be designated by the State and approved by the Secretary of Agriculture as part of the Federal-aid highway system.”

- ↑ In 1953 the average State gasoline tax was about 5 to 6 cents per gallon, and the Federal tax was 2 cents per gallon. Thus, the States and the Government were collecting ½ cent per mile for providing and maintaining the public highways. On top of this the toll roads collected about 1½ cents per mile in tolls so turnpikes cost their users about four times as much as free roads. There were, of course, offsetting economies in time, operating costs, and distance savings which made the turnpikes attractive.

New Jersey’s Garden State Parkway, one of the early examples of excellent design for high-speed, access-controlled roads.

Toll road authorities were created in Connecticut, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Kansas, Kentucky, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Texas and Virginia. By the end of 1954, these authorities had 1,382 miles of toll roads under construction at costs estimated to total $2.3 billion, and they were making plans and studies for 3,314 additional miles estimated to cost $3.75 billion. The 1,239 miles of toll roads already completed as of January 1955 represented an investment of $1.55 billion.[51]

With few exceptions, these toll roads followed the routes selected by the PRA and the States for the Interstate System, and they represented the heaviest trafficked portions of that System outside the cities. At the height of the toll road boom, the turnpike authorities were investing their funds in interstate highways at about three times the rate of the State highway departments.

It is not an exaggeration to say that most of the motoring public first learned the safety and comfort of driving on access controlled roads on the turnpikes. The toll roads provided the example that later led to mandatory control of access on the Interstate System. The toll roads were high-speed divided highways with wide rights-of-way. Their geometric standards equaled or bettered AASHO’s “desirable” standards for the Interstate System. In addition, the turnpike authorities spent considerable sums to provide amenities for their users—rest areas, landscaping, built-in safety features. A few, notably New Jersey’s Garden State Parkway and portions of the New York Thruway, were planned with the two roadways totally independent of and largely concealed from each other—an advanced technique of highway design pioneered by the PRA and the National Park Service on the Baltimore–Washington Parkway. Most toll roads, however, were built in the monotonous tradition of long tangents that had dominated highway engineering for decades. Nevertheless, the toll roads, as a class, set a high standard of excellence that was hard for the State highway departments with their limited budgets to match. They provided highly visible yardsticks by which to measure the glaring inadequacies of the public highways and whetted the public appetite for better free roads.

With the great success of many of the early turnpikes, their excess capital was used to build and support less profitable roads, appearing to establish a never-ending requirement for tolls.

Tolls Forever

The feasibility of the original Pennsylvania Turnpike was assured by Federal grants of $29.5 million which greatly reduced the part of its cost that would have to be financed by revenue bonds and recovered in tolls from the road users. The success of the turnpike convinced many proponents of toll roads in and out of Congress that the much-needed improvement of the main interstate highways could be achieved by Federal subsidy of toll roads, especially those with marginal revenue potential, or even by a system of federally owned toll roads. A bill was introduced in the 80th Congress to permit the use of Federal funds on toll roads, along with the perennial bill to authorize transcontinental Federal toll expressways.[52]

These proposals were opposed by the PRA and a long list of organizations representing highway users. The PRA’s argument was that toll roads were wasteful and solved only a part of the problem. To reduce the cost of collecting tolls, the access points had to be spaced far apart, denying the use of the road to local and short haul traffic[N 1] The States or counties would have to build duplicating parallel free roads to handle this local traffic at greater total expense than it would take to build a free expressway originally.

By 1948 business was so good on the Pennsylvania Turnpike that toll collections were running far ahead of the requirements for retiring the bonds. When the Legislature authorized the 100-mile extension east to the Delaware River, the Turnpike Commission merged the financing of this extension with that of the original toll road by floating new bonds, part of which were used to pay off the original bond issue. Later other extensions were all financially tied together so that revenue from the profitable sections of the system supported the weaker sections.

This pattern of financing, long used by the Port of New York Authority,[N 2] was copied in other States. Connecticut placed the income from the Merritt and Wilbur Cross Parkways and the Charter Oak Bridge in a revolving fund to support the bonds for a new toll expressway from Greenwich to Killingly. Maine applied the income from its first turnpike to finance a northern extension to Augusta.

This trend alarmed many State highway administrators who foresaw a situation of perpetual tolls on their main highways. In 1950 the Deputy Director of the New York Department of Public Works warned that the proliferation of toll roads would stifle free transportation and injure the national welfare.[53] The Engineering News-Record cautioned against the danger that toll authorities would perpetuate themselves long after the original excuse for their existance (shortage of funds) has passed. “As a result, the publicly owned toll highway of today can become just as pernicious an evil as the privately owned toll road of a century or more ago.”[54]

Congress Sets National Policy on Toll Roads

In 1954 the New York Thruway Authority and the New Jersey Highway Authority agreed to connect the thruway and the Garden State Parkway at the State line. However, trucks were prohibited on the parkway, which meant that southbound trucks on the thruway would have to exit at the State line and continue their journey on the public roads. Critics of toll roads pointed to this decision as one of many examples of uncoordinated regional planning by the toll authorities. The connection, they said, should have been made to the New Jersey Turnpike instead of the parkway, and the decision as to where to connect should have been made by the State highway authorities in Albany and Trenton rather than by the toll road authorities.[55]

There was also widespread criticism of allowing the toll roads to preempt the Interstate highway locations and thus condemn the free roads in those locations to a generation of inadequacy.

The Bureau of Public Roads had played a decisive role in coordinating the regional planning of the Federal-aid system by the States. However, the BPR had no influence with the toll authorities since they had not received any Federal funds. One of the reasons advanced by proponents of Federal aid for toll roads was that such aid would give the Government some control over them—at least to the extent of requiring that the roads be freed of tolls after the bonds were paid off.

The 83d Congress (1953–1954) considered the thorny problem of Federal aid for toll roads but left it unsettled by directing the Secretary of Commerce to make a study and report his recommendations to the next Congress. This report, Progress and Feasibility of Toll Roads and Their Relation to the Federal-Aid Program submitted to the 84th Congress in 1955, showed that on January 1, 1955, there were 1,239 miles of completed “arterial toll roads” in the United States, plus 1,382 miles under construction and an additional 3,314 miles authorized.[56] Many hundreds of miles in the third category had not been studied, and their possibilities for revenue bond financing were unknown.

The BPR analyzed all highways, toll or free, that were not already adequately improved for future traffic up to the year 1984 or definitely scheduled for such improvement. The analysts found that about 6,900 miles of heavy-traffic roads were feasible for revenue bond financing, and of these, 6,700 miles were on the Interstate System routes.[57] Whether there could be additional self-supporting toll roads, therefore, would depend upon the policies of the Federal Government and the States in the use of public funds to improve the Interstate System. “Assurance of public funds to provide reasonably early completion of the system would soon spell the end of revenue-bond financing of roads in the system. Continuation of the present inadequate allocation of funds to this system, however, can only serve to increase the mileage that would be potentially feasible as tool roads.”[58]

The report then went on to describe the inadequate local service given by toll roads and the resulting need for parallel free highways. “Thus, even though a toll road may be readily self-liquidating, it can never relieve some public agency from the responsibility of continuing to provide local service . . . On the other hand, a properly located and designed free road can serve both the through and local traffic.”[59]

The Secretary recommended that there be no Federal support or encouragement of new toll roads but that Congress permit the integration of existing toll roads into the System where they followed Interstate routes and met Interstate standards and where there were available reasonably satisfactory alternate free roads. No toll roads should be permitted on any other Federal-aid system.

Congress incorporated these recommendations in the new law, and also authorized the use of Federal funds on approach roads connecting acceptable toll roads to the free portions of the Interstate System. This last was conditioned on the State’s agreement to free the benefited section of toll road after retirement of the original bonds.

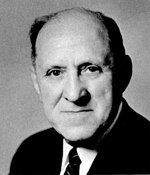

New Leadership for the Bureau of Public Roads

When Commissioner MacDonald reached the statutory retirement age in 1951, only a handful of the oldest employees could remember a time when he had not been in charge of the Bureau of Public Roads. The Bureau’s budget had increased from $69 million in fiscal year 1919, when he assumed control over what was then a minor bureau in the Department of Agriculture, to $485 million in 1951—about half of the Commerce Department’s total budget. In those 32 years, MacDonald had supervised the spending of over $6.6 billion of Federal aid and forest highway funds without a hint of impropriety, although not without controversy at times. He had served under six Presidents and up to that time had the longest continuous tenure of any important policymaking officer of the Government.

Under “the Chief,” as he was known for most of his career, the Bureau of Public Roads had grown from a small but capable and dedicated group of road experts to the most prestigious highway organization in the world.

When the Korean emergency developed into a national crisis, President Truman recognized the confidence MacDonald enjoyed with the Congress and with the State highway departments by persuading MacDonald to continue as Commissioner for the remainder of his Administration.

Commissioner MacDonald retired in March 1953. In his farewell remarks to the press, he emphasized the importance of continuing the traditional Federal–State partnership:

‘first, it is a workable plan to accomplish a continuing program that involves both local and national services; second, it sets a pattern in harmony with the concepts of federal government.’

The original Federal Highway Act of 1916, he said, ‘recognized the sovereignty of the states and the authority retained by the states to initiate projects. All through the legislation since then, the same mechanism of checks and balances has been maintained evenly so that the states and the federal government both have to agree before they can accomplish a positive program.’[60]

Freed from the inhibitions of his office, MacDonald went on to state that the Federal gasoline tax revenue should be returned to the States as Federal aid, and that “it is time to give serious consideration to a charge for use of what we may call extra facilities such as controlled access express highways.”

President Eisenhower appointed Francis V. duPont as Commissioner in April 1953. A civil engineer, duPont had been chairman of the Delaware Highway Commission for 23 years and was thoroughly familiar with Federal and State road policies. In announcing his appointment, Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks made a point of also declaring that the administration had no intention of recommending that the Government retire from the taxation of gasoline as had been so loudly demanded by the 1953 Governors Conference. He also said that there were no plans to make any serious changes in the Bureau of Public Roads or its functions.

Mr. duPont assumed control over the Bureau with the expressed intention of making changes slowly, and then only after a complete review of its operations. In his first appearance before the House Subcommittee on Roads he suggested few changes in national policy. Toll roads, he said, were economically feasible at only a very few locations and would not solve the overall road finance problem. Congress, he recommended, should accelerate a solution to the vexing truck size and weight problem not by threats, but by hints that Congress would act if the States and industry did not. He thought the Federal-aid apportionment formula should be changed to give greater weight to the population factor.[61]

The Drive for More Federal Aid

The Korean emergency coupled with the continuing steady increase in vehicle registrations imposed new strains on the highways. Freight carried by highways increased by one-third in a single year, from 107 billion ton-miles in 1949 to 142 billion ton-miles in 1950.[62] The traffic increases affected all classes of highways but were felt most acutely on the Interstate System, a number of sections of which were carrying over 50,000 vehicles per day.

Contractors were plentiful, and construction prices reasonably stable; still, the States were barely able to keep up with traffic, especially in the cities. Some States, with BPR approval, adopted a stage construction policy for urban expressways, building them in little pieces to “provide immediate relief at the most seriously congested points, with a view to subsequent construction of an entire facility.[63]

The real problem with all the States was a shortage of funds. Nearly all of them had increased their gasoline taxes and registration fees, but these increases barely offset the inflation in maintenance and construction costs. In their straitened circumstances, State resentment focused on the Federal gasoline tax which had originally been imposed by Congress as an emergency revenue measure but had been continued after the war and which was yielding about $1 billion annually. Some State governors also pointed to the Federal excise taxes on automobiles, trucks, tires, oils and greases which yielded another billion dollars to the Government. Since Federal aid to the States was currently only half a billion dollars, this in the eyes of the governors was diversion of road-user funds on a massive scale—the very practice penalized by the 1934 Hayden-Cartwright Act when indulged in by the States.

The congressional road committees held exhaustive hearings in 1953 in preparation for the 83d Congress biennial highway bill.

The legislation that emerged in 1954, without acknowledging any tie between Federal-aid appropriations and the Federal gasoline tax, boosted the appropriations 50 percent above any previous level, to $875 million for fiscal years 1956 and 1957, including $175 million specifically earmarked for the Interstate System and increased the Federal share on Interstate projects to 60 percent. Congress also requested a comprehensive study of the costs of completing the several systems of highways in the States—to be completed along with a new toll road study.

The House Subcommittee on Roads had argued the merits of toll financing, but in the end, Congress avoided the toll road problem in drafting the final version of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954 except to ask for a study and to allow Connecticut the right to charge tolls on its proposed expressway from Greenwich to Killingly after repayment of the Federal funds previously expended on the road.

In the 1954 Act, Congress, for the first time, relaxed some of the Government’s tight control over the spending of Federal-aid funds. For secondary road projects under the Secondary Road Plan, as it came to be known, the BPR was required to approve only system changes and programing of funds and to inspect and accept completed projects. By agreement between the State and the BPR, all other details of planning, contracting and building secondary roads could be handled by the State without detailed Federal supervision. This relieved the BPR of much tedious detail and enabled it to concentrate available personnel on primary and Interstate projects.

Inflation and shortage of funds during the Korean emergency made even simple maintenance difficult for the States.

The Grand Plan

Before the Secretary could prepare either the toll road study or the highway cost study requested by Congress, President Eisenhower announced his own plan for bridging the gap between highway construction and highway needs. Choosing the annual conference of State Governors as his forum, the President asked the governors for their cooperation and help to work out the details of “ ‘. . . a grand plan for a properly articulated system that solves the problems of speedy, safe, transcontinental travel—intercity communication—access highways—and farm-to-market movement—metropolitan area congestion—bottlenecks—and parking.‘ ’[64] To overcome the accumulated deficiencies, he called for spending $5 billion per year for 10 years, in addition to normal expenditures.[65][N 1]

The President’s bold plan was well received. The conference appointed a Governors Highway Committee to advise the President, particularly in the matter of financing the program. The conference also refrained from further attempts to get the Federal Government to retire from gasoline taxation.

At this time, the President did not have a detailed blueprint for his Grand Plan, and he realized that a great deal of study would be needed before a definite plan could be presented to Congress for action. He appointed a Federal Interagency Committee to study highway policy within the Government and also asked General Lucius D. Clay, who had served as military governor of Germany, to head up an advisory committee of prominent citizens to determine the needs and recommend a financing plan. The Clay Committee, as it was thereafter known, held hearings and enlisted the help of AASHO and outstanding experts from public agencies, the highway industry and highway user groups.

The best estimate of needs came from AASHO which, with the help of the BPR, had updated its estimate of the needs of the Federal-aid systems in 1953. That estimate was $35 billion to make the 673,137-mile Federal-aid system adequate for 1953 traffic. Projecting the needs ahead to 1964 and adding an allowance for other roads not on any Federal-aid system, AASHO and the Committee arrived at a figure of $101 billion for the total capital needs that would have to be met by 1964.[N 2] The Committee estimated that the existing sources of revenue would produce only $47 billion to meet these needs, leaving a financial gap of about $54 billion.[68]

The Clay Committee Report

In December 1954 the Governors Conference Special Highway Committee[N 3] submitted a report recommending that the Government assume the entire financial responsibility for the Interstate System and that Congress continue its 50-50 support for the remaining Federal-aid systems so long as the Government continued to levy excise taxes on motor fuels, lubricants and motor vehicles. The States and local governments, the report continued, should pay for the remaining costs, amounting to about 70 percent of the total program.[70]

The Clay Committee agreed substantially with the governors in this division of the financial burden, but recommended that the States pay 5 percent of the cost of the Interstate System. To finance the Federal share, which they estimated at $31 billion,[N 4] the Committee recommended that Congress create a Federal Highway Corporation with authority to issue $20 billion in 32-year bonds, paying the interest and amortization charges out of the future income from the Federal taxes on fuel and lubricants. The Committee estimated that the cost of the Interstate System financed by this method plus the cost of the regular Federal-aid authorizations continued at the current rate would about equal the yield of the fuel and lubricating oil taxes, projected without increase in rates to 1987.[72]

President Eisenhower received the Clay Committee report, A 10-Year National Highway Program, in January 1955. A few months earlier he had asked for and received from Congress a $6 billion increase in the national debt limit to cover deficits incurred in the Administration’s antirecession program. The President, therefore, welcomed the Clay proposal to finance most of the road program outside the budget, and he included it as a major feature of the Administration’s highway bill which he sent to Congress in March 1955.

Meanwhile, Senator Albert Gore of Tennessee, Chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Roads, was holding hearings on his own highway bill—an expanded version of the traditional biennial Federal-aid authorization providing $1.6 billion annually of Federal funds which the States would be required to match with $1.27 billion.

Both the President’s bill and the Gore bill came under strong attack in the committee hearings. Former Commissioner duPont testified that the old pay-as-you-go system was too little, too late to meet present needs: that it would take 32 years to complete the Interstate System at the rate proposed by Senator Gore.[73][N 5] The new Commissioner of Public Roads, Charles D. Curtiss, said that according to a poll of the State highway departments, only 19 States would be able to match the Federal funds proposed in the Gore bill, but 43 would be able to match the smaller amount in the Administration’s bill.[74] Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr., of Virginia, chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee denounced the Administration’s plan as a scheme to evade the debt limit and remove the highway program from the control of Congress. Asserting that it would cost $12 billion in bond interest, Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico called the Administration’s bill a “bankers bill” rather than a road bill. Rural interests branded the Administration’s proposal to pledge all Federal gasoline tax revenue above $622 million per year to back the Federal Highway Corporation's bonds as a 32-year strait-jacket for rural highways.

- ↑ In calendar year 1953, these normal expenditures amounted to $3.5 billion for State-administered highways, $1.2 billion for local roads and $1.2 billion for urban highways and streets—a total of $5.9 billion.[66]

- ↑ The BPR’s study ordered by Congress in 1954 showed that the total of the needs to reach adequacy of all highways by 1964 was $126.1 billion ($100.8 billion for construction, $19.4 billion for maintenance and $5.9 billion for administration).[67]

- ↑ This Committee was composed of Governor Walter J. Kohler, Jr., of Wisconsin, Chairman, and Governors Frank J. Lausche (Ohio), Howard Pyle (Arizona), John Lodge (Connecticut), Lawrence W. Wetherby (Kentucky), Paul Patterson (Oregon), Allan Shivers (Texas), and Robert F. Kennon of Louisiana, Chairman of the 1954 Governors Conference, ex officio.[69]

- ↑ This total was divided as follows: $25 billion for the Interstate System, including essential urban arterial connections; $3.15 billion for the remainder of the Primary System ; $750 million for the Federal-aid Urban System, $2.10 billion for the Federal-Aid Secondary System and $225 million for forest highways.[71]

- ↑ Mr. duPont resigned as Commissioner of Public Roads in December 1954 in order to give his full attention to promoting the President’s highway program. Charles D. Curtiss, a long-time career engineer who had served 11 years as deputy commissioner, was appointed to the vacancy January 14, 1955.

The Engineering News-Record came out strongly for the Administration bill, and particularly for the 10-year limit on completion of the Interstate System. “The real crux of the matter rests in the fact that we need a whole new system of highways just as soon as we can get it, and no adequate pay-as-you-go plan has yet been seriously proposed to assure that result.”[75] Proponents of pay-as-you-go financing, the article continued prophetically, were gambling that there would be no inflation in the 30 years or more it would take to build the Interstate System from current revenues.

Defeat of the President’s Plan