America's Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program/Part 1/Chapter 3

Federal Aid

for

Roads and Canals

Zone’s Trace—First Federally Aided Road

In March 1796, Colonel Ebenezer Zane, the founder of Wheeling, Virginia, petitioned Congress for permission to build a post road overland through the territory northwest of the Ohio River to the important river port of Limestone, Kentucky (now Maysville). Such a route, Zane said, would be 100 miles shorter than the windings of the Ohio River, on which 15 men with their boats were then engaged in transporting the mails, and would also be immune to interruption by floods, floating ice or low water. The road would afford far faster mail service while saving at least three-quarters of the $4,000 annual cost of operating the mail route. Furthermore, the proposed road would provide a shorter and safer route for travelers both to and from the West.

As his only compensation for building the road, Zane asked that he be allowed to locate United States military bounty land warrants totaling three square miles where his road crossed the Muskingum, Hockhocking, and Scioto Rivers.

Colonel Zane’s request was approved by Congress in the act of May 17, 1796, with the stipulation that Zane establish ferries upon the three rivers and operate them at rates of ferriage to be established by any two judges of the Northwest Territory.[1]

Zane’s first road was no more than a pack trail, but as soon as it was finished, the Government established a mail route over it from Wheeling to Maysville and beyond to Lexington, Kentucky, and eventually Nashville, Tennessee. Zane’s Trace played an important part in opening southeastern Ohio to settlement. It was also used by hundreds of flatboatmen returning on foot or horseback to Pittsburgh and upriver towns from downriver ports as far away as New Orleans.

By 1803, the road was chopped out wide enough for wagons to pass. The portion between Wheeling and Zanesville became a part of the National Road after 1825, and the rest became an important turnpike in the 1830’s.

The grant to Zane appears to be the first instance of local road subsidy by the Federal Government, but it did not have much influence on Federal policy afterward. Furthermore, the aid extended was not particularly generous, since, in any event, Zane had the legal right as a Revolutionary War veteran to exchange his warrants (and any he might buy from other veterans) for public land. In reality, the act gave Zane only the right to locate his lands in advance of the general public and at strategic locations where he could later profit from their resale to settlers.

Financing Roads in New States

The lack of roads, and the resources to build them, was a serious impediment to the development of the lands north and west of the Ohio River. The United States Government owned practically all of the undeveloped land, the sale of which was its main source of revenue. What could be more logical than to set aside a portion of the revenues from the sale of public lands for building roads and canals, thus, promoting not only the development of the new territories, but land sales as well?

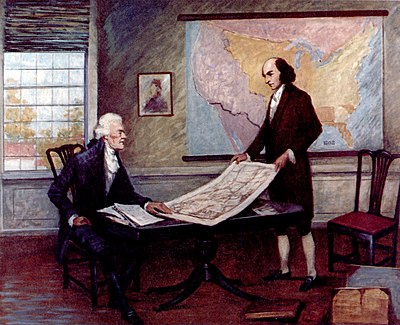

The Gallatin Report.

In 1801 Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, in a letter to Representative William B. Giles of Virginia, suggested that one-tenth of the net proceeds of public land sales be applied to the building of roads, but only with the consent of the States through which such roads might pass.[2] This idea was incorporated in the Ohio Statehood Enabling Act of 1802, except that only 5 percent of the proceeds of land sales was to be set aside for roads. Ohio’s constitutional convention modified the 5-percent plan by insisting that three-fifths of the road money be spent on roads “within” the State and under the control of the Legislature. This change was accepted by Congress in 1803 by an act which established a “2 percent fund” derived from the sale of public lands to be used under the direction of Congress for constructing roads “to and through” Ohio.[3]

Following the Ohio precedent, Louisiana, Indiana, Mississippi, Illinois, Alabama, and Missouri, on their admission to statehood, were given 3 percent grants for roads, canals, levees, river improvements, and schools. Congress later granted an additional 2 percent to these States, except Indiana and Illinois, which, with Ohio, had already received the equivalent in expenditures on the National Road. The additional 2 percent funds were used by these States for railroads.

The remaining 24 States admitted between 1820 and 1910 received 5 percent grants, except Texas and West Virginia, in which the Federal Government had no lands. Of the 22 States that received grants, 9 were authorized to use them for public roads, canals, and internal improvements and 13 for schools.[4]

The First National Transportation Plan

Secretary Gallatin, at the request of the U.S. Senate, made the first national inventory of transportation resources in 1807. Out of this study came his report on roads and canals in 1808, a remarkably comprehensive and forward-looking document which, unfortunately, had little immediate effect on U.S. transportation policy. Gallatin clearly understood the vital role of transportation for increasing the wealth of nations. As he stated in his report:

It is sufficiently evident that, whenever the annual expense of transportation on a certain route, in its natural state, exceeds the interest on the capital employed in improving the communication, and the annual expense of transportation (exclusively of tolls), by the improved route, the difference is an annual additional income to the nation. Nor does in that case the general result vary, although the tolls may not have been fixed at a rate sufficient to pay to the undertakers the interest on the capital laid out. They, indeed, when that happens, lose; but the community is nevertheless benefited by the undertaking. The general gain is not confined to the difference between the expense of the transportation of those articles which had been formerly conveyed by that route, but many which were brought to market by other channels will then find a new and more advantageous direction; and those which on account of their distance or weight could not be transported in any manner whatever, will acquire a value, and become a clear addition to the national wealth.[5]

Gallatin then went on to show that in developed countries, such as France and England, there is sufficient concentration of wealth and population that private capital will flow into undertakings, such as canals and turnpikes, offering only remote and moderate profit. By contrast, in underdeveloped countries, such as the United States, commerce will not support expensive roads and canals, except near a few seaport cities. Even these facilities will not be fully productive until they become integrated into larger networks which only the general government can finance and carry through.

Gallatin, therefore, proposed that Congress launch a great national program of roads, canals and inland navigations to be completed in 10 years and which he estimated would cost about $20 million. To finance this program, he recommended annual appropriations of $2 million, amounting to less than one-seventh of the Government’s annual income and less than half of the fiscal surplus at that time. This modest investment would, he said, not only stimulate internal development, but would also enhance the value of the yet unsold Federal lands by far more than the cost of the program, while contributing to the national defense. Lastly and most importantly, “Good roads and canals will shorten distances, facilitate commercial and personal intercourse, and unite, by a still more intimate community of interests, the most remote quarters of the United States. No other single operation, within the power of the Government, can more effectually tend to strengthen and perpetuate that Union which secures external independence, domestic peace, and internal liberty.”[6]

The works proposed by Gallatin were, first, a series of great canals along the Atlantic coast connecting the natural bays and estuaries into one continuous waterway for the carriage of heavy freight. Supplementing this waterway, there would be a light-duty turnpike from Maine to Georgia for passengers, mail and light goods hauling. The second part of the plan was to form communications between the four great Atlantic rivers and the Western rivers by river improvements, short canals and four heavy-duty freight turnpikes across the mountains. These would be supplemented by internal roads to Detroit, St. Louis and New Orleans. The third part was to open inland navigation between the Hudson River and the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, plus a canal around the Niagara rapids to open the Great Lakes to sloop navigation as far as the extremities of Lake Michigan.

The First National Plan For Financing Internal Improvements

Gallatin’s bold scheme was years ahead of its time and, further, it was proposed at a time when Congress was already divided by the Cumberland Road debate. It was shelved during the War of 1812. However, the plan had many friends in and out of Congress, chief of whom was John C. Calhoun, South Carolina.

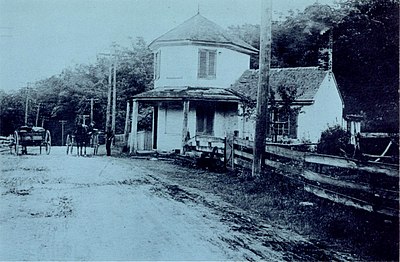

This scene at the Fairview Inn, near Baltimore, is typical of the heavy travel on the Cumberland Road. Heavily loaded freight wagons, herds of stock, stagecoaches, and buggies depended on the inns along the way for food and rest after long weary hours on the road.

Bridge over the Monocacy River near Frederick, Maryland, built about 1810 by Baltimore bankers on the road connecting Baltimore with the old Cumberland Road.

In 1816 the question of chartering a second National Bank was before Congress. Calhoun introduced a bill providing that the bonus of $1.5 million to be paid by the Bank for the new charter, plus the dividends on the Government’s stock in the Bank for the next 20 years, be set apart as a permanent fund for internal improvements. This fund was to be apportioned among the States in proportion to their representation in the lower House of Congress, and the improvements were to be built by the Federal Government with the assent of the States in which they might be located. Since the annual dividends on the Government’s $7 million of stock were $560,000, the bill would provide a 20-year program of nearly $13 million.

Urging adoption of this bill, Calhoun pointed to the need for roads for defense, but primarily to encourage commerce and cement political union:

If we look into the nature of wealth, we find that nothing can be more favorable to its growth than good roads and canals . . . Many of the improvements contemplated are on too great a scale for the resources of the States or individuals ; and many of such nature that the rival jealousy of the States, if left alone, might prevent.

Let us then bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space. It is thus the most distant parts of the Republic will be brought within a few days travel of the centre; it is thus a citizen of the West will read the news of Boston still most from the press. The mail and the press are the nerves of the body politic.[7]

Calhoun’s bill was bitterly opposed in both the House and Senate, not only by the strict constitutionalists, but also by those who thought the money should be applied to tax relief and retirement of the war debt. Others said the States might refuse assent to the improvements or try to dictate their location for political expediency and, thus, defeat the purpose of the plan. Still others branded the bill as a scheme to mulct the wealthy States in which adequate roads and canals had already been built at great expense, for the benefit of the poor and improvident States.

In the end, however, the bill passed both the House and Senate by narrow margins, to be vetoed on March 3, 1817, by President Madison, who declared it to be an improper interpretation of the constitutional power of the General Government to regulate commerce and provide for the national defense.[8] The motion to override the veto failed in the House, ending the first attempt to set up a continuing national plan for internal improvements.[9]

The Cumberland Road

On March 29, 1806, President Jefferson approved an act which directed that the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint three commissioners to lay out and build a road from the head of navigation on the Potomac River at Cumberland, Maryland, to a point on the Ohio River.[10] The act set certain minimum standards for the proposed road and appropriated $30,000 from the proceeds of Ohio land sales to finance the location of the road and to start construction. The debates attending the passage of this act exposed the bitter rivalries and jealousies between the eastern seaboard States over the development of the lands beyond the Ohio River.

The seaport cities in particular feared the advantage that a Government-financed road might give in competition for the western trade. Strict constructionists of the U.S. Constitution denied that the Federal Government had the authority to build roads at all, except possibly in the territories. Proponents of Federal roadbuilding on the other hand, asserted that authority to build roads was implied under the “general welfare” clause of the Constitution.

In the end, the issue was decided by those of both parties who felt strongly that the bonds between the East and the West should be strengthened in the interest of national unity, and the act passed the House by a narrow margin. At least one representative from every State voted in favor of the road.

President Jefferson lost no time in selecting the three commissioners and in applying to the legislatures of Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania for permission to build the road within their boundaries. The first two States gave their assent without restriction, but Pennsylvania held back and conditioned its approval on the road’s passing through the towns of Uniontown and Washington.[11]

It took the commissioners 4 years to select the route, and another 8 years to push the construction through from Cumberland to Wheeling, Virginia, the head of low-water navigation on the Ohio River. This road was 30 feet wide, with the central 20 feet paved by the Tresaguet method, that is, with several layers of small broken stone placed over a foundation of 7-inch stones. It was cleared 66 feet wide, ditched, and provided with drains and bridges. The cost, paid out of the Ohio 2 percent land fund, was about $1.75 million, or an average of $14,000 per mile.[N 1][12]

From the time the first section was opened in 1813, the Cumberland Road came under heavy traffic, so heavy in fact, that the stone surface was worn away almost as fast as it was built. The commissioners were unable, with the funds available, to provide the systematic and continual maintenance required by broken stone roads; and they were without power to protect the road from the depredations of travelers and local residents.[N 2] Consequently, the condition of the road steadily deteriorated, despite efforts to repair the worst damage.

- ↑ This cost included maintenance during the 8-year construction period.

- ↑ Freighters ripped up the shoulders by descending the steep hills with locked wheels. Local inhabitants fenced in parts of the right-of-way, dug into the banks, dragged logs over the road, and even stole broken stone from the road bed.[13]

Old Cumberland Road at Wills Creek just west of Cumberland, Md.

To provide a regular source of funds for maintenance, Congress in 1822 passed an act authorizing the collection of tolls from users of the road. President Monroe vetoed this act on the ground that it was an unwarranted extension of the power vested in Congress to make appropriations, “under which power, with the consent of the States through which the road passes, the work was originally commenced, and has so far been executed.”[14] Collection of tolls, the President said, implied a power of jurisdiction or sovereignty which was not granted to the Federal Government by the Constitution and could not be unilaterally conveyed by any State without a constitutional amendment. It was one thing to make appropriations for public improvements, but an entirely different thing to assume jurisdiction and sovereignty over the land whereon those improvements were made.[15] This has been the Federal position on highway grants to the States down to the present day.

Old Cumberland Road approaching Chestnut Ridge Mountains in Pennsylvania about 1899.

Transfer to State Control

In the 10 years following President Monroe’s veto, Congress made occasional and niggardly appropriations for maintaining the Cumberland Road, but these were inadequate to preserve it under ever-increasing traffic[N 1] The supporters of the road finally realized that there was little chance that a Congress bitterly divided over the issue of federally-financed internal improvements would ever make adequate provisions for keeping it in repair. State operation as a toll road seemed to be the only solution to the dilemma, and between 1831 and 1833, the Legislatures of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia agreed to accept and maintain their sections of the National Road. Maryland and Pennsylvania, which had the oldest and worst-worn sections conditioned their acceptance upon the Government’s first putting the road into a good state of repair and erecting toll gates.[19]

The Government spent nearly $800,000 in 1833, 1834, and 1835 for repairing the road east of the Ohio River, the work being done under the supervision of the Army Corps of Engineers. This work was principally rebuilding the pavement according to McAdams’ method, adding broken stone to replenish the wear of traffic. As soon as each section was reconstructed, the States assumed jurisdiction and maintenance. By the end of 1835 the National Road, from Cumberland to the Ohio-Indiana line, was national no longer.

- ↑ For the years 1823 to 1827, a total of $55,000 was appropriated for repairs, an average of only $88 per mile per year—hardly enough to keep the ditches open.[16] An idea of the traffic can be had from the fact that in 1822 one of the five commission houses at Wheeling unloaded 1,081 wagons, averaging 3,500 pounds of freight each, and the annual total freight bill from Baltimore to Wheeling was estimated at $390,000.[17] In addition, hundreds of stagecoaches and private vehicles used the road daily. Nineteen thousand pigs were driven over the road in 1831, some in droves of 600 animals.[18]

Westward Extension of the National Road

As soon as the Cumberland Road reached the Ohio River, there was agitation to extend it westward through Ohio and the newly-admitted States of Indiana and Illinois. These States, like Ohio, had provisions in their acts of admission for setting aside 2 percent of the income from sales of public lands for road improvements.

In 1820 Congress appropriated $10,000 for laying out a road between Wheeling and the left bank of the Mississippi River. However, the road did not officially get under way until 1825, when Congress made another appropriation to start construction and to extend the surveys to the permanent seat of government in Missouri, passing through the seats of government of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.[20] Thereafter, the Government spent slightly over $4 million to push the road as far west as Vandalia, then the capital of Illinois.

From Wheeling to Vandalia the road was laid out with Roman straightness in an 80-foot right-of-way, but except in eastern Ohio, it did not approach the high construction standard of the Cumberland Road east of the Ohio River. This was partly because of the scarcity of good roadbuilding stone, which had to be hauled long distances. In Indiana and Illinois the road was only a cleared and graded dirt track.

Old tollhouse on Cumberland Road near Frostburg, Md.

The annual appropriation bills continued to be bitterly opposed in Congress and passed by increasingly narrower margins. After 1832 there was sentiment in Congress to use the money appropriated for the National Road to build a railroad west from Columbus, Ohio, and an unsuccessful amendment to the appropriation bill for 1836 proposed to do just that. The last regular appropriation for the Road was in 1838, but construction continued until 1840 when the funds ran out.[21]

By its act of 1831, Ohio accepted the road as fast as it was completed by the Federal engineers and put it under toll. The road was never finished in Indiana and Illinois, and in 1848 Congress ceded to the former “all the rights and privileges of every kind belonging to the United States as connected with said road. . . .” A similar act for Illinois was passed in 1856. In 1879 Congress granted Ohio the right to make the road free, “Provided, That this consent shall have no effect in respect to creating or recognizing any duty or liability whatever on the part of the United States.”[22]

The National Road never reached the Mississippi, but petered out in the Illinois prairies. Its ultimate demise could have been forecast in 1831 when Congress agreed to turn the eastern sections over to the States for operation and maintenance. The end was due not so much to the constitutional and sectional objections that had plagued the road from the beginning, as to the growing feeling in the country and in Congress that roads and canals were already obsolete for long-distance transportation. The day of the railroad was at hand.

The Maysville Turnpike Veto

The course of highway policy in the United States was profoundly influenced by two presidential vetoes. President Monroe’s veto of Federal toll collections on the Cumberland Road has already been mentioned. President Jackson’s veto on May 27, 1830, of turnpike stock subscriptions established national policy with respect to internal improvements of purely local character.

In January 1827, the Kentucky Legislature petitioned Congress to provide Federal aid for an artificial road from Maysville to Lexington, Kentucky. This would be an extension of the mail route leaving the National Road at Zanesville, Ohio, and following Zane’s Trace to the Ohio River. In 1828 an appropriation bill in the U.S. Congress authorizing this road failed by only one vote in the Senate.[23]

The Legislature then incorporated the Maysville, Washington, Paris, and Lexington Turnpike Road Company to build the road, with the provision that 1,500 shares of stock be reserved for subscription by the U.S. Government. In a parallel action, Congress passed a bill authorizing the Secretary of the Treasury to subscribe to 1,500 shares in the Company in the name and for the use of the United States.[24]

1830—The Maysville Turnpike.

The President vetoed this bill on the ground that the proposed improvement was of purely local, and not national, importance.

It has no connection with any established system of improvements; it is exclusively within the limits of a State, starting at a point on the Ohio River and running out 60 miles to an interior town, and even as far as the State is interested conferring partial instead of general advantages.

However, he went on,

What is properly national in its character or otherwise is an inquiry which is often extremely difficult of solution . . .

If it be the wish of the people that the construction of roads and canals should be conducted by the Federal Government, it is not only highly expedient, but indispensably necessary, that a previous amendment to the Constitution, delegating the necessary power and defining and restricting its exercise with reference to the sovereignty of the States, should be made. . . .[25]

Jackson was not personally hostile to internal improvements; in fact, less than a year before in his first annual message to Congress he had recommended distributing the embarrassing annual surplus Federal revenue among the States to be used by them for internal improvements.

The Maysville Turnpike veto not only put an end to all thought of national aid to local road improvements, but it also forestalled any efforts that might be made to provide Federal aid to such genuinely national promotions as the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Over 20 years would pass before Congress would provide any significant subsidy for railroads.

The Maysville Turnpike was eventually completed with State and private funds. The road had long been a mail route, so the Government insisted it could run the mails over it without paying tolls. This question was settled by the courts in favor of the Turnpike Company in 1838; thereafter mail contractors paid the same fees as the general public.[26]

The Michigan Road

The first settlements in Indiana were along the Ohio River and the Wabash and White Rivers. By 1826 settlement had reached the southern limits of the Potowatomi Indian lands, which extended from the Wabash River to Lake Michigan. At this time the only overland communication with central Indiana was along a poor dirt wagon road from Indianapolis, the capital, to Madison on the Ohio River.

In October 1826, the U.S. Government concluded a treaty with the Potowatomi under which the Indians ceded a large area of northern Indiana and southern Michigan to the United States. Among other things this treaty provided that the State of Indiana should be given a strip of land 100 feet wide for a road commencing at Lake Michigan and extending to the Wabash River, plus a section (640 acres) of good land contiguous to every mile of the road, and in addition, a section of land for every mile the road was extended southward from the Wabash River. Congress, in March 1827, authorized Indiana to locate and build this “Michigan Road” in accordance with the treaty, from Lake Michigan to Indianapolis and southward to Madison, using funds from the sale of the designated Indian lands.[27] From 1830, when the Legislature authorized construction to begin, until 1840, the sale of the Indian lands yielded $241,332, with several hundred acres remaining to be sold. As noted earlier, Indiana also received grants from Congress under its Statehood Act from the proceeds of public land sales within the State. For a decade, these were the two principal sources of funds for wagon roads. When they were exhausted, Indiana, like its neighbors, turned to private financing and chartered plank road and turnpike companies to finish the job.

Land Grants to the States for Wagon Roads

The grant of Potowatomi lands to Indiana was not the first Federal land grant to a State for roads, or the last. The first significant Federal land grant was in February 1823 when Congress granted Ohio a 120-foot right-of-way for a public road from the lower rapids of the Miami River of Lake Erie to the western boundary of the Western Reserve. To finance the road, Congress gave the State all the public lands for 1 mile on each side of the road, with the proviso that they could not be sold for less than $1.25 per acre.[28]

Congress subsidized a toll turnpike from Columbus to Sandusky by another grant to Ohio in 1827. This grant gave the State every alternate section of land abutting the west side of the road.[29]

The Maysville Turnpike veto put an end to further wagon road subsidies, other than the National Road, until the Civil War. Between 1863 and 1869, however, Congress made 10 separate grants of land to Michigan, Wisconsin, and Oregon for certain “military” wagon roads. These, with the previous grants to Indiana and Ohio, totaled 3,560,000 acres,[30] or about 5,500 square miles—an area somewhat larger than Connecticut.

Federal Land Subsidies for Canals

Prior to President Jackson’s administration (1829–1837), Federal largesse extended not only to roads, but canal and river improvements as well. In March 1822, Congress granted Illinois a 180-foot right-of-way for a canal to connect the Illinois River and Lake Michigan. This act authorized the State to take construction materials from adjacent public lands and, in addition, granted Illinois one-half of the public lands in a strip 10 miles wide centered on the canal. In return, the State agreed that the canal would be “a public highway for the use of the Government of the United States, free from any toll or charge whatever, for any property of the United States, or any persons in their service.”[31]

This Illinois River-Lake Michigan Canal grant was the first land subsidy voted by Congress for internal improvements, and became a precedent for the subsequent granting of immense tracts of the public domain.

An act of May 24, 1828, which, as a subsidy to canals, granted Ohio 500,000 acres to be selected from any available public lands within the State, became the precedent for the general act of September 4, 1841, granting 500,000 acres each to Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Alabama, Missouri, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Michigan and to each public land State admitted thereafter.[N 1] These grants were to be used for specified internal improvements, such as roads, railways, bridges, canals, river improvements, and draining of swamps.[32]

Military Roads—The Natchez Trace

Until the construction of the Cumberland Road and the Pennsylvania Road, the only outlets for the produce of the Ohio River Valley were by packhorse trains across the mountains or downriver in flatboats and rafts. At New Orleans the crews sold the vessels and their cargoes and either embarked by sea for eastern ports or returned overland by foot or horseback through the lands of the friendly Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians, to the Mero Settlements, now Nashville, Tennessee. From here, they could find their way to the upper valley by trails through central Kentucky to Zane’s Trace and beyond.

In 1801 the Government negotiated agreements with the Choctaws and Chickasaws “ ‘to lay out, open, and make, a convenient wagon road through their land, between the settlements of Mero District (Nashville), in the State of Tennessee, and those of Natchez, in the Mississippi Territory.’ ”[33] Upon conclusion of these agreements, the Army began widening the old Indian trails, eight companies of infantry working south from Mero District and six companies northward from Natchez. This military road, later called the Natchez Trace, was completed in 1803.[34] Although it served a peaceful purpose to thousands of returning flatboat-men, this road was initially conceived with strategic military ends in view, in the event the United States should become embroiled with Spain over the port of New Orleans.

The Jackson Military Road

Following the War of 1812, Congress authorized a more direct military road from Nashville to New Orleans, which would shorten the distance between those cities by 220 miles.

The First and Eighth Infantry Regiments began work on this road in June 1817, completing it in May 1820. Two congressional appropriations totaling $15,000 were only a small part of the cost of this road. Over 75,800 man-days of labor were expended on it by the troops, and the total disbursement from military funds was well over $300,000. For this, the Army cleared a right-of-way 40 feet wide through dense forest, graded an earth road 35 feet wide, built 20,000 feet of corduroy causeways, and over 35 substantial bridges from 60 to 200 feet long. By 1824 most of this road south of Columbus, Mississippi, was grown over and abandoned.[35]

Military Roads on the Frontiers

The Army built more than 100 other military wagon roads in the period from 1807 to 1880, most of them in the territories. Their total length was well over 21,000 miles, and they cost at least $4 million, not counting the labor of the troops.[36] Some were built by the troops and some by hired labor.

- ↑ States admitted after 1889 received cash grants for educational and penal institutions instead of acreage.

1809—The Natchez Trace.

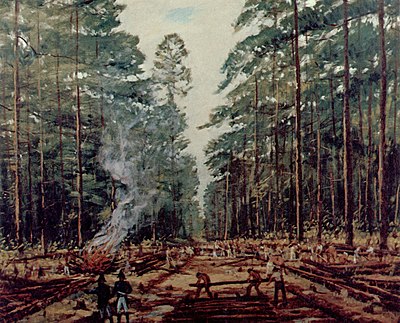

1820—General Jackson’s Military Road.

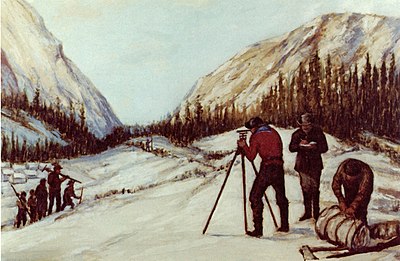

1862—The Mullan Road.

These roads were crude—mere wagon tracks across the prairies or traces chopped through the heavy timber of Florida or Wisconsin—but in the early years of settlement, they were often the only roads the settlers had. Among them were the famous Santa Fe Trail from Kansas City to Santa Fe, New Mexico, marked by the Army, following a route originally beaten by traders and trappers, and Colonel Cooke’s Road from Santa Fe to San Diego, pioneered by the Army in 1846. The Army reopened the 400-mile Old Spanish Trail from Pensacola to St. Augustine, Florida, in 1824–1830. Military roads radiated like the spokes of a wheel from strategic Detroit toward Chicago, Grand Rapids, Saginaw and Cleveland, and in 1838 a 512-mile wagon road was made from Ft. Snelling, Minnesota Territory, to Ft. Leavenworth in Kansas Territory.

One of the most remarkable of the military wagon roads was located and built by Lieutenant John Mullan in 1858 to 1862 from Fort Benton in Dakota Territory, the head of steamboat navigation on the Missouri River, across the Rocky Mountains to Old Fort Walla Walla on the Columbia River. For 20 years afterward, this road was the only way open to emigrants into western Montana and northern Idaho.[37]

In the single year 1866 there passed over the Mullan Road 20,000 persons travelling back and forth, including 2,000 miners stampeding into Montana, 1,500 head of horses, 5,000 head of cattle, 6,000 mules loaded with freight, 83 wagons and $1 million in money.[38]

During the overland migrations of the 1850’s and 1860’s, the Army improved and marked most of the pioneer wagon trails and used them to supply its garrisons. Between 1850 and 1869 some of these trails were transcontinental mail routes used by the Butterfield Overland Mail, the Pony Express, and other mail contractors.

After the Government divested itself of the National Road, military roads were practically the only Federal subsidies to local transportation. These were meager indeed, compared to the largesse that was distributed by Congress to the railroads. REFERENCES

- ↑ A. B. Hulbert, Historic Highways of America, Vol. 11 (Arthur H. Clark, Co., Cleveland, 1904) pp. 157, 158.

- ↑ P. D. Jordon, The National Road (Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1948) pp. 71, 72.

- ↑ A. Rose, Historic American Highways—Public Roads of the Past (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1953) p. 66.

- ↑ Office of Federal Coordinator of U.S. Transportation, Public Aids to Transportation, Aids to Railroads and Related Subjects, Vol. II (GPO Washington, D.C., 1938) p. 7.

- ↑ A. Gallatin, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on Roads and Canals, S. Doc. No. 250, 10th Cong, 1st Sess., p. 724 (1808).

- ↑ Id., p. 725.

- ↑ Annals of Congress, 14th Cong., 2d Sess. (Gales and Seaton, Washington, D.C., 1854) pp. 851–854.

- ↑ Id., pp. 1061, 1062.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra, note 3, p. 66.

- ↑ A. B. Hulbert, Historic Highways of America, Vol. 10 (Arthur H. Clark, Co., Cleveland, 1904) p. 26.

- ↑ Id., p. 54.

- ↑ P. D. Jordan, supra, note 2, p. 88.

- ↑ A. B. Hulbert, supra, note 11, pp. 58, 59.

- ↑ Id., p. 59.

- ↑ Id., pp. 194–197.

- ↑ P. D. Jordan, supra, note 2, p. 217.

- ↑ Id., p. 238.

- ↑ Id., p. 170.

- ↑ A. B. Hulbert, supra, note 11, p. 73.

- ↑ Id., p. 90.

- ↑ P. D. Jordan, supra, note 2, p. 175.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra, note 3, p. 57.

- ↑ Id., p. 58.

- ↑ A. B. Hulbert, supra, note 1, pp. 171, 172.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra., note 3, p. 58.

- ↑ A. C. Rose, The Michigan Road, Road Builders News, Vol. 38, No. 7, Aug. 1938, pp. 12–17.

- ↑ Off. of Fed. Coordinator, supra, note 4, p. 7.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Id., p. 8.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Id., p. 9.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra, note 3, pp. 44, 45.

- ↑ Id., p. 44.

- ↑ Id., p. 51.

- ↑ Military Roads. A Brief History of the Construction of Highways by the Military Establishment and a Gazetteer of the Military Roads in Continental United States (National Highway Users Conference, Washington, D.C., 1935) pp. 1-14.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra, note 3, pp. 80, 81.

- ↑ R. E. Huxt, Steamboats in the Timber (Binfords and Mart, Portland, 1952) App., p. 205.