America's National Game/Chapter 18

CHAPTER XVIII.

1888-89

AN EVENT of considerable importance in its influence upon the American national game was the world's tour of Professional National League Base Ball Players in the winter of 1888-89. Base Ball had been advancing in popularity with such rapid strides in our own land during preceding years, that I felt the time had come when this great pastime should be introduced wherever upon the globe conditions were favorable to our peculiar form of outdoor sport. The first Base Ball tour abroad, it will be remembered, had been to the British Isles in 1874. It was quite natural, therefore, that, in mapping out this new enterprise, attention should be diverted to the opposite direction. It was known that many Base Ball lovers lived in the Hawaiian Islands, and that the British colonists of the South Pacific Isles, New Zealand and Australia, were nearly all devotees of field sports, for they had a racial love for outdoor games and enjoyed a climate that made their playing possible nearly the entire year. To the Antipodes, then, the tour was first proposed, and Mr. Leigh S. Lynch, who had wide experience as a manager of dramatic enterprises, was sent to Australia, via Honolulu and New Zealand, with instructions. His duty was to make arrangements, secure accommodations, schedule exhibitions, and prepare the public for the unusual visitation.

The securing of teams for this voyage in the interests of Base Ball missionary effort was not easy. It was proposed to take the players of the Chicago team, of which club I was then President, with one or two additions, as a whole, and no difficulty was experienced in interesting them; but the forming of an opposing nine, to be selected from the best players in other National League organizations, was beset with many obstacles. To openly ask for volunteers was out of the question, because it would be certain to result in a deluge of applications from undesirable players in the fraternity. To choose those best equipped to play the game meant the asking of many who could not go. It was absolutely essential that all who did go should be men of clean habits and attractive personality, men who would reflect credit upon the country and the game. Finally, when the ranks had been filled, it was found that several, on one pretext or another, were determined to withdraw, and it became necessary to fill their places hurriedly. Happily, however, capable men were available, and the corps lost nothing in playing capacity by reason of the action of those who dropped out.

The teams as completed for the voyage were composed of the following players:

Chicagos—Mark Baldwin and J. K. Tener (now Governor of Pennsylvania), pitchers; Tom Daly, catcher; A. C. Anson, first base and captain; N. F. Pfeffer, second base; Thomas Burns, third base; E. N. Wilhamson, short-stop; M. Sullivan, left field; J. Ryan, center field; Robert Pettit, right field.

All-Americas—John Healy, Indianapolis, and E. W. Crane, New York, pitchers; J. C. Earl, Cincinnati, catcher; G. A. Wood, Philadelphia, first base; F. H. Carroll, Pittsburgh, second base; H. Manning, Kansas City, third base; John M. Ward, New York, shortstop and captain; Jas. Fogarty, Philadelphia, left field; Ed. Hanlon, Pittsburgh, center field; Tom Brown, Boston, right field.

Other members of the party were: My mother, Mrs. Harriet I. Spalding; Mrs. Anson, Mrs. Williamson, Mrs. Lynch, Harry Clay Palmer, of the New York Herald; Newton Macmillan, of the New York Sun, and Mr. Good-friend, of the Chicago Inter-Ocean. George Wright and W. Irving Snyder also accompanied the party, Wright officiating as umpire at most games played.

Our special train, which consisted of two Pullman sleepers and a dining car, left Chicago for San Francisco on the 20th of October, 1888, following the close of the Base Ball season of that year. En route across the continent the teams played exhibition games at St. Paul, Minneapolis, Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, Omaha, Hastings, Denver, Colorado Springs and Salt Lake City. On the Pacific Coast, games were played at Los Angeles and San Francisco. Everywhere on this land journey the Base Ball Missionaries received splendid ovations.

On Sunday, the 18th of November, we sailed out through the Golden Gate, on the steamer "Alameda," bound for Honolulu, our first port of call, After a full

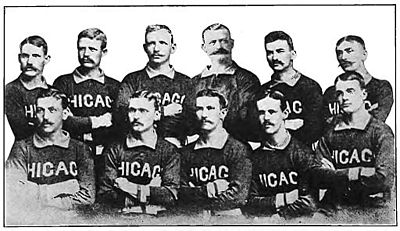

Burns Daley Pettit Sullivan Baldwin Tener Healy Carroll Wood Brown Manning

Williamson Pfeffer Anson A.G. Spalding Ward Fogarty Simpson

Mascot George Wright Ed. Hanlon Earl

A game of Base Ball between the great American teams had been announced for Saturday. It was now Sunday. Honolulu had the "lid on." What was to be done?

The American game had at that time, nearly a quarter of a century ago, taken a strong hold of the popular heart at Honolulu. Here was the home of Alexander J. Cartwright, founder of the first Base Ball club ever organized—Father of the famed Knickerbockers. Many Americans were there who had played the game at home, and the natives also were developing some skill at the pastime. The widely-heralded news of our coming, accompanied by the assurance that the game would be presented by its most celebrated and proficient exponents, had created interest among lovers of the sport and had aroused much curiosity on the part of the general public. Everybody wanted to witness the game; but, alas, it was Sunday. We were to leave late that evening; therefore it was Sunday—or never. Petitions came flooding in upon me for a Sunday game. I at once made an investigation, which satisfied me that the missionaries who were looking after the moral welfare of the natives had closed the doors against Sunday entertainments good and tight. There was no doubt about it; Sunday ball was as "taboo" in Honolulu as had been a whole lot of things when the heathens were in full control of their island. I was importuned, almost with tears, to ignore the law. I was assured that the authorities were not likely to interfere in the face of such a popular clamor. A purse of $1,000 had been raised as a bonus for the game. That money was greatly needed just then, for we had embarked on an enterprise which would involve the expenditure of much cash.

We had counted on some gate receipts at Honolulu; but here was the law forbidding Sunday ball. There was only one thing to do. We obeyed the letter and spirit of the law, called the game off, and left a lot of disgruntled Americans and disappointed Kanakas, to say nothing of the much-coveted shekels.

I may as well take occasion here to define my views on the subject of Sunday ball playing. I am not, nor have I ever been, opposed to Sunday ball so far as the game itself is concerned. I believe in many of the arguments advanced in favor of the playing of League games on that day. I know it is the one day in the week when a great many of those who care for the game can have leisure, without too great loss, to witness the sport. I know it is a better way for the average American to pass Sunday afternoon than many others resorted to by the average American for entertainment on that day. I know that boys and men, by hundreds and thousands, who regularly patronize Sunday ball would be engaged in practices much more inimical to their wellbeing if no games were played on Sunday. I know the need of the money that is received for Sunday games by the management, especially of minor league clubs, whose gate receipts on weekdays are inadequate to meet expenses. All this I know, and yet I also know that it is of paramount importance that the laws of every city and state and country should be respected and upheld; that the youth of every community should be educated to honor and obey the laws. And so, whenever this problem presents itself for my decision, I first ask the question, "Is Sunday ball playing legal?" If it is, I say "Play Ball." If not, my answer is the same as that given to the petitioners at Honolulu. This rule obtained throughout our world tour. Wherever and whenever the law forbade, we played no games. Wherever and whenever the law allowed, we played games on Sunday.

Notwithstanding the mutual disappointment of visitors and visited at Honolulu as regards the failure to pull off a game of Base Ball, there was no law forbidding King Kalakaua, then on the Hawaiian throne, to entertain our party, which he certainly did in royal manner.

Sailing from Honolulu on Monday morning, November 26th, we were on the Pacific for over two weeks before reaching Auckland, New Zealand, on the 10th of December. Here a game was played to the great delectation of the New Zealanders, very few of whom had ever seen it, though many were proficient at cricket.

Leaving Auckland, we sailed direct for Sydney, Australia, where we arrived December 14th. We were now in "topsy-turvy" land for sure. It was the middle of December, and right in the midst of summer's heat, with Christmas only ten days off and the fields ripe with the golden glow of harvest. We played at Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Ballarat, being received everywhere with demonstrations of welcome, and much interest in the game was elicited at all points in the great island continent.

Originally our tour had been planned to end in Australia, retracing via Honolulu, as we had sailed; but before leaving the Pacific Coast I had been studying the situation and found that the distance from Australia around the world to New York was about the same as via San Francisco. During the voyage I had discussed the matter with the players, and as they were unanimously and enthusiastically in favor of the globe trip, we decided to return home that way.

Therefore, on the morning of January 8th, 1889, we left Melbourne homeward bound via Suez Canal, taking the steamer "Salier." Sixteen days later we arrived at the Island of Ceylon, and, upon landing at Colombo, we startled the natives of that far-off island of the seas by an exhibition of American ball playing, on January 26th, 1889.

Following this came the "flight into Egypt," with a game on the desert's sands in front of the Great Pyramids, and near enough to use one for a backstop. Afterwards the whole company was photographed en groupe on the Egyptian Sphinx, to the horror of the native worshippers of Cheops and the dead Pharaohs.

On the 19th of February, having reached the Bay of Naples, we went ashore, and under the shadow of Vesuvius showed the Italians how to play the great American game.

Rome was naturally our next point to visit, and there we played in the Villa Borghese, formerly the beautiful home of an Italian prince. The visit to Rome was one of the most enjoyable of the entire tour, so much was there to see of historic interest. King Humbert of Italy honored our game by his presence, and a number of American students at the great Roman College of the Catholic Church were in attendance. Following the visit to Rome, we played a game at Florence, and then departed for France.

One of the events of the European trip was the game played at Paris, within the shadow of the great Eiffel Tower, then under process of construction for the Exposition soon to occur. The American colony was out in full force at this game; but the Parisians did not seem to catch on to any appreciable extent, though many were present.

The reception of our company in England was one of the great triumphs of the world tour. This function took place at the club house of the Surrey County Cricket Club. It was the occasion of the first public welcome of the tourists to Great Britain, and there were present the Duke of Beaufort, the Duke of Buccleugh, the Earls of Sandsborough, Coventry, Sheffield and Chesborough, together with Lords Littleton, Oxenbridge and Hawke, beside Sir Reginald Hanson, Attorney General Sir W. C. Webster, with the Lord Mayor of London, the American Consul and others of note.

It is worthy of note that the English hosts of this and other occasions were astonished to see the professional American ball players enter into the spirit of these receptions, not only attired in full evening dress, but with a degree of familiarity with social requirements that was quite foreign to professional cricketers.The inaugural game in London was played at Kennington Oval grounds, and though the day was a typical London day in March, cold, wet and foggy, making ball playing difficult and its enjoyment almost impossible, there was a large crowd present to see the Americans. Soon after the contest opened the Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward) and his brother-in-law. Prince Christian, came upon the field. The game was suspended while the American ball players gave three cheers and a tiger for the Prince, which demonstration was heartily seconded by the multitude, the Prince bowing his acknowledgments.

The party was escorted to the royal box, and; when the game was resumed, at the request of one of the gentlemen-in-waiting I took my place between the brother princes to explain to them the points of the game, with which, of course, they were not familiar. They asked me numerous questions bearing upon the various plays as the sport proceeded. The Prince of Wales became particularly animated in his appreciation of the activity of the pastime.

"What's that for?" "Why is he doing that?" and similar queries, came frequently from his lips.

Now it happened that day that the Prince, who was short of stature, had a carbuncle or boil, or some sort of swelling on his neck, making it very difficult for him to turn his head. Standing at his side, I found it extremely awkward, from my height of six feet two, to keep him advised without bending low and talking in his ear. Under these circumstances, I did the perfectly natural thing for an American sovereign to do—just what I would have done had President Taft been witness of the game and needed instruction—which, of course, he would not. Stepping to one side, where I had observed an empty chair, I brought it over, placed it between their Royal Highnesses, sat down and resumed my comments in answer to their interrogatories.

As the game progressed, the scions of the great House of Guelph became more and more impressed, so that when Anson made one of his long hits and started for third, the Prince, with an ejaculation inspired by intense interest, slapped me on the leg and exclaimed, "That was a hard clip!" or something to that effect. And when Williamson, a moment later, on a swift grounder, right past first baseman, but far enough out so that Wood couldn't get it, reached his base by a pretty slide, I felt perfectly justified in returning the familiarity, and, tapping the late King of England on the shoulder, asked him, "What do you think of that?"

Now there have been a good many printed versions of this story. It may be, as claimed by some who were present, that all Britain held its breath while I took a seat in the presence of Royalty. I distinctly remember that Hon. Newton Crane, the American Consul, laughed immoderately that evening, as he and I drove together from the grounds, at what he termed my breach of "court etiquette." However, as I recall the incident after this lapse of years, I see nothing in it to cause me to blush. If I violated the code of court etiquette, I must plead that I was not at court, but at an American ball game. If I sat in the presence of Royalty, it is certain that Royalty sat in mine. If I tapped the future King of Great Britain on the shoulder, it was nothing more offensive than a game of tag, for he had first slapped me on the leg. If British Royalty honored us by its presence, which I am willing to concede, we repaid it by a splendid exhibition of our National Game. No, I am not able to see wherein honors were not quite even.

It was at this game that the Prince of Wales wrote his oft incorrectly quoted critique on the game.

The New York Herald—or rather, the London edition of that paper—had presented each spectator upon entering the grounds with a card, containing several questions calculated to draw out a consensus of English opinion on the game of Base Ball. The reporter of this paper explained to the Prince in my presence the object of these cards and expressed the wish that the Prince would give his opinion. The reporter, pencil in hand, stood ready to jot down the replies of the Prince when the latter said:

"Give me a card."

He then hurriedly wrote something and handed the card over to me that I might see how he had answered the questions. As I recall them from memory, his words were briefly as follows:

"I consider Base Ball an excellent game; but Cricket a better one."

Dignified courtliness, amiable courtesy, tactfulness and honest conviction are all forcefully presented in the hastily penned sentence of the Prince. They well illustrate the qualities that made King Edward famous as one of the world's great diplomats.

"The King is dead; long live the King."

It is estimated that at least 60,000 people witnessed the games of Base Ball played at this time in the British Isles at London, Bristol, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford, Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool, Belfast and Dublin.

The welcome given our party on the return home by devotees of the game at New York was one of the great events of the remarkable tour. It was held at Delmonico's. A. G. Mills, President of the National League, presided. At his right sat A. G. Spalding, Chauncey Depew, Daniel Dougherty, Henry E. Howland, W. H. McElvey, and U. S. Consul W. Griffen. On his left were Mayor Chapin, of Brooklyn—the Mayor of New York was unable to be present; Mayor Cleveland, of Jersey City, Mark Twain, Rev. Joseph Twitchell, and officers of the New York and Manhattan Clubs. Among the guests were also members of the alumni of Harvard, Yale and Princeton Universities. Theodore Roosevelt, afterward President, was present at this banquet. As may readily be understood, the after-dinner speeches, from such a galaxy of talent, were replete with brilliant and witty thoughts.

Such, briefly, is the story of the world's tour of 1888-89. In all respects it was a splendid success. In a financial way, it cost in round figures the sum of $50,000, and the receipts were ample to pay all expenses. It presented exhibitions of the American National Game in foreign lands belting the globe. It created interest in the game in countries where it had never been seen before, and where from that day to this the sport has been growing in popular favor. It gave to the masses everywhere an opportunity to witness a pastime peculiarly American, and it showed to all the world that one may be at the same time a professional ball player and a gentleman.

Mike Kelly, in reminiscent mood, one day near the close of his great career gave out this interview to the New York Sun:

"The lightest I ever played ball was 157 pounds with my uniform on. I had India rubber in my shoes then. I was like I was on springs, and I was playing with the best ball team ever put together—the Chicagos of 1882. I bar no team in the world when I say that. I know about the New York Giants, the Detroits and the Big Four, the 1886 St. Louis Browns and all of them, but they were never in it with the old 1882 gang that pulled down the pennant for Chicago. Then was when you saw ball playing, away up in the thirty-second degree. That was the crowd that showed the way to all the others. They towered over all ball teams like Salvator's record dwarfs all the other race horses. Where can you get a team with so many big men on its pay roll? There were seven of us six feet high, Anson, Goldsmith, Dalrymple, Gore, Williamson, Flint and myself being in that neighborhood. Larry Corcoran and Tommy Burns were the only small men on the team. Fred Pfeffer was then the greatest second baseman of them all. All you had to do was to throw anywhere near the bag, and he would get it—high, wide or on the ground. What a man he was to make a return throw; why, he could lay on his stomach and throw 100 yards then. Those old sports didn't know much about hitting the ball either; no, I guess they didn't. Only four of us had led the League in batting—Anson, Gore, Dalrymple and myself. We always wore the best uniforms that money could get, Spalding saw to that.. We had big wide trousers, tight-fitting jerseys, with the arms cut out clear to the shoulder, and every man had on a different cap. We wore silk stockings. When we marched on a field with our big six-footers out in front it used to be a case of 'eat 'em up, Jake.' We had most of 'em whipped before we threw a ball. They were scared to death."