Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography/Morse, Jedidiah

|

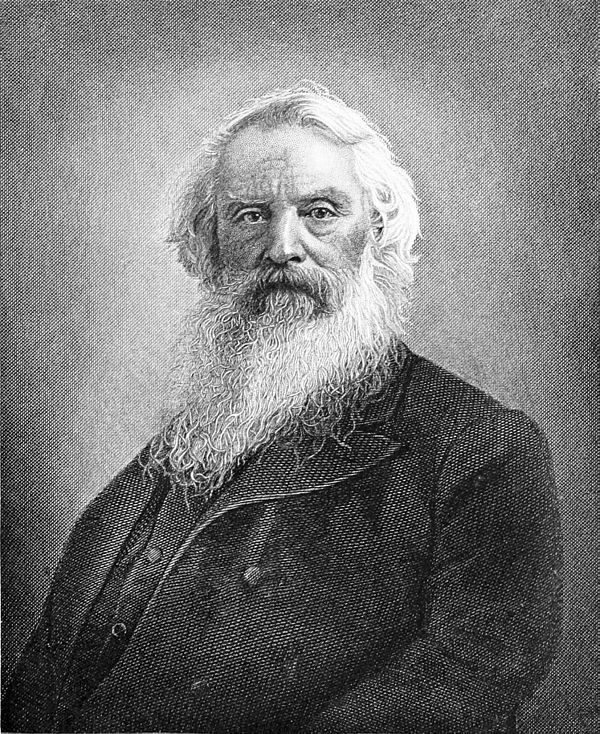

MORSE, Jedidiah, clergyman, b. in Woodstock, Conn., 23 Aug., 1761; d. in New Haven, Conn., 9 June, 1826. He was graduated at Yale in 1783, and in September of that year established a school for young ladies in New Haven, meanwhile pursuing theological studies under Dr. Jonathan Edwards and Dr. Samuel Watts. In the summer of 1785 he was licensed to preach, but continued to occupy himself with teaching. He became a tutor at Yale in June, 1786, but, resigning this office, was ordained on 9 Nov., 1786, and settled in Medway, Ga., where he remained until August of the following year. He spent the winter of 1787-'8 in New Haven in geographical work, preaching on Sundays to vacant parishes in the vicinity. In May, 1787, he was invited to preach at Charlestown, Mass., where he was installed on 30 April, 1789. This pastorate he held until 1820, when he removed to New Haven, and there spent the remainder of his life. He took great interest in the subject of civilizing and Christianizing Indians, and in 1820 he was appointed by the secretary of war to visit and observe various tribes on the border, in order to ascertain their actual condition, and to devise the most suitable means for their improvement. This work occupied his attention during two winters, and the results of his investigations were embodied in a “Report to the Secretary of War on Indian Affairs” (New Haven, 1822). In 1795 he received the degree of D. D. from the University of Edinburgh, and he was an active member of the Massachusetts historical society and of various literary and scientific bodies. Throughout his life he was much occupied with religious controversy, and in upholding the faith of the New England church against the assaults of Unitarianism. Ultimately his persevering opposition to the so-called liberal views of religion brought on him a persecution that affected deeply his naturally delicate health. He was very active in 1804 in the movement that resulted in enlarging the Massachusetts general assembly of Congregational ministers, and in 1805 unsuccessfully opposed, as a member of the board of overseers, the election of Henry Ware to the Hollis professorship of divinity in Harvard. Dr. Morse did much toward securing the foundation of Andover theological seminary, especially by his successful efforts in preventing the establishment of a rival institution in Newburg, which had been projected by the Hopkinsians. He participated in the organization of the Park street church in Boston in 1808, when all the Congregational churches of that city, except the Old South church, had abandoned the orthodox faith. In 1805 he established the “Panopolist” for the purpose of illustrating and defending the commonly received orthodoxy of New England, and continued its sole editor for five years. This journal still exists as “The Missionary Herald.” Dr. Morse published twenty-five sermons and addresses on special occasions; also “A Compendious History of New England,” with Rev. Elijah Harris (Charlestown, 1804); and “Annals of the American Revolution” (Hartford, 1824). He early showed considerable interest in the study of geography, and adapted from some of the larger English works a text-book that was so frequently copied by his pupils that he published it as “Geography Made Easy” (New Haven, 1784), and it was the first work of that character published in the United States. Subsequently he issued “American Geography” (Elizabethtown, 1789); “The American Gazetteer” (London, 1789); and “Elements of Geography” (1797). These books had an extensive circulation, and gained for him the title of “Father of American Geography.” — His son, Samuel Finley Breese, founder of the American system of electro-magnetic telegraph, b. in Charlestown, Mass., 27 April, 1791; d. in New York city, 2 April, 1872, was graduated at Yale in 1810, and in that institution received his first instruction in electricity from Prof. Jeremiah Day, also attending the elder Silliman's lectures on chemistry and galvanism. In 1809 he wrote: “Mr. Day's lectures are very interesting; they are upon electricity; he has given us some very fine experiments, the whole class, taking hold of hands, form the circuit of communication, and we all received the shock apparently at the same moment. I never took an electric shock before; it felt as if some person had struck me a slight blow across the arms.” His college career was perhaps more strongly marked by his fondness for art than for science, and he employed his leisure time in painting. He wrote to his parents during the senior year: “My price is five dollars for a miniature on ivory, and I have engaged three or four at that price. My price for profiles is one dollar, and everybody is willing to engage me at that price.” When he was released from his college duties, he had no profession in view, but to be a painter was his ambition, and so he began art studies under Washington Allston, and in 1811 accompanied him to London, where soon afterward he was admitted to the Royal academy. He remained in London for four years, meeting many celebrities and forming an intimate friendship with Charles R. Leslie, who became his room-mate. Under the tuition of Allston and Benjamin West he made rapid progress in his art, and in 1813 exhibited a colossal “Dying Hercules” in the Royal academy, which was classed by critics as among the first twelve paintings there. The plaster model that he made to assist him in his picture gained the gold medal of the Adelphi society of arts. This was given when Great Britain and the United States were at war, and was cited as an illustration of the impartiality with which American artists were treated by England. The first portrait that he painted abroad was of Leslie, who paid him a similar compliment, and later he executed one of Zerah Colburn. He then set to work on an historical composition to be offered in competition for the highest premium of the Royal academy, but, as he was obliged to return to the United States in August, 1815, this project was abandoned. Settling in Boston, he opened a studio in that city, but, while visitors were glad to admire his “Judgment of Jupiter,” his patrons were few. Finding no opportunities for historic painting, he turned his attention to portraits during 1816-'17, visiting the larger towns of Vermont and New Hampshire.

Meanwhile he was associated with his brother, Sidney E. Morse, in the invention of an improved pump. In January, 1818, he went to Charleston, S. C., and there painted many portraits, his orders at one time exceeding 150 in number. On 18 Oct., 1818, he married Lucretia Walker in Concord, N. H., but in the following winter he returned to Charleston, where he wrote to his old preceptor, Washington Allston: “I am painting from morning till night, and have continual applications.” Among his orders was a commission from the city authorities for a portrait of James Monroe, then president of the United States, which he painted in Washington, and which, on its completion, was placed in the city hall of Charleston. In 1823 he settled in New York city, and after hiring as his studio “a fine room on Broadway, opposite Trinity churchyard,” he continued his painting of portraits, one of the first being that of Chancellor Kent, which was followed soon afterward by a picture of Fitz-Greene Halleck, now in the Astor library, and a full-length portrait of Lafayette for the city of New York. During his residence there he became associated with other artists in founding the New York drawing association, of which he was made president. This led in 1826 to the establishment of the National academy of the arts of design, to include representations from the arts of painting, sculpture, architecture, and engraving. Morse was chosen its president, and so remained until 1842. He was likewise president of the Sketch club, an assemblage of artists that met weekly to sketch for an hour, after which the time was devoted to social entertainment, including a supper of “milk and honey, raisins, apples, and crackers.” About this time he delivered a series of lectures on “The Fine Arts” before the New York athenæum, which are said to have been the first on that subject in the United States. Thus he continued until 1829, when he again visited Europe for study, and for three years resided abroad, principally in Paris and the art centres of Italy.

During 1826-'7 Prof. James F. Dana lectured

on electro-magnetism and electricity before the

New York athenæum. Mr. Morse was a regular

attendant, and, being a friend of Prof. Dana, had

frequent discussions with him on the subject of his

lectures. But the first ideas of a practical application

of electricity seem to have come to him while

he was in Paris. James Fenimore Cooper refers to

the event thus: “Our worthy friend first

communicated to us his ideas on the subject of using the

electric spark by way of a telegraph. It was in

Paris, and during the winter of 1831-'2.” On 1

Oct., 1832, he sailed from Havre on the packet-ship

“Sully” for New York, and among his

fellow-passengers was Charles T. Jackson (q. v.), then lately

from the laboratories of the great French physicists,

where he had made special studies in

electricity and magnetism. A conversation in the

early part of the voyage turned on the recent experiments

of Ampère with the electro-magnet. When

the question whether the velocity of electricity is

retarded by the length of the wire was asked, Dr. Jackson

replied, referring to Benjamin Franklin's experiments,

that “electricity passes instantaneously over

any known length of wire.” Morse then said: “If the

presence of electricity can be made visible in any

part of the circuit, I see no reason why intelligence

may not be transmitted instantaneously by

electricity.” The idea took fast hold of him, and

thenceforth all his energy was devoted to the development

of the electric telegraph. He said: “If it

will go ten miles without stopping, I can make it go

around the globe.” At once, while on board the

vessel, he set to work and devised the dot-and-dash

alphabet. The electro-magnetic and chemical

recording telegraph essentially as it now exists was

planned and drawn on shipboard, but he did not

produce his working model till 1835 nor his relay

till later. His brothers placed at his disposal a

room on the fifth floor of the building on the corner

of Nassau and Beekman streets, which he used

as his studio, workshop, bedchamber, and kitchen.

In this room, with his own hands, he first cut his

models; then from these he made the moulds

and castings, and in the lathe, with the graver's

tools, he gave them polish and finish. In 1835 he

was appointed professor of the literature of the arts

of design in the University of the city of New

York, and he occupied front rooms on the third

floor in the north wing of the university building,

looking out on Washington square. Here he

made his apparatus, “made as it was,” he says,

“and completed before the first of the year 1836.

I was enabled to and did mark down telegraphic

intelligible signs, and to make and did make

distinguishable signs for telegraphing; and, having ar-

rived at that point, I exhibited it to some of my

friends early in that year, and among others to

Prof. Leonard D. Gale.” His discovery of the relay

in 1835 made it possible for him to re-enforce the

current after it had become feeble owing to its

distance from the source, thus making possible

transmission from one point on a main line, through

great distances, by a single act of a single operator.

In 1836-'7 he directed his experiments mainly to

modifying the marking apparatus, and later in

varying the modes of uniting, experimenting with

plumbago and various kinds of inks or coloring-matter,

substituting a pen for a pencil, and devising

a mode of writing on a whole sheet of paper

instead of on a strip of ribbon. In September,

1837, the instrument was shown in the cabinet of

the university to numerous visitors, operating

through a circuit of 1,700 feet of wire that ran back

and forth in that room. At this time the apparatus,

which is shown in the accompanying illustration,

was described by Prof. Leonard D. Gale as

consisting of a train of clock-wheels to regulate the

motion of a strip of paper about one and a half

inches wide; three cylinders of wood, A, B, and C,

over which the paper passed, and which were

controlled by the clock-work D that was moved by the

weight E. A wooden pendulum, F, was suspended

over the centre of the cylinder B. In the lower

part of the pendulum was fixed a case in which a

pencil moved easily and was kept in contact with

the paper by a light weight g. At h was an electro-magnet,

whose armature was fixed on the pendulum.

The wire from the helices of the magnet

passed to one pole of the battery I, and the other to

the cup of mercury at K. The other pole of the

battery was connected by a wire to the other cup of

mercury, J. The portrule represented below the

table contained two cylinders connected by a band.

M shows the composing-stick in which the type

were set. At one end of the lever O O was a fork

of copper wire, which was plunged when the lever

was depressed into the two cups of mercury J and

K, while the other end was kept down by means of a

weight. A series of thin plates of type metal, eleven

in number, having one to five cogs each, except one

which was used as a space, completed the apparatus.

His application for a patent, dated 28 Sept., 1837,

was filed as a caveat at the U. S. patent-office, and

in December of the same year he made a formal

request of congress for aid to build a telegraph-line.

The committee on commerce of the house of

representatives, to which the petition had been

referred, reported favorably, but the session closed

without any action being taken. Francis O. J.

Smith, of Maine, chairman of the committee,

became impressed with the value of this new application

of electricity, and formed a partnership with

Mr. Morse. In May, 1838, Morse went to Europe

in the hope of interesting foreign governments in

the establishment of telegraph-lines, but he was

unsuccessful in London. He obtained a patent in

France, but it was practically useless, as it required

the inventor to put his discovery into operation

within two years, and telegraphs being a government

monopoly no private lines were permissible.

Mr. Morse was received with distinction by scientists

in each country, and his apparatus was

exhibited under the auspices of the Academy of

sciences in Paris, and the Royal society in London.

After an absence of eleven months he returned to New York in May, 1839, as he writes to Mr. Smith, “without a farthing in my pocket, and have to borrow even for my meals, and, even worse than this, I have incurred a debt of rent by my absence.” Four years of trouble and almost abject poverty followed, and at times he was reduced to such want that for twenty-four hours he was without food. His only support was derived from a few students that he taught art, and occasional portraits that he was commissioned to paint. In the mean time, his foreign competitors — Wheatstone in England, and Steinheil in Bavaria — were receiving substantial aid, and making efforts to induce congress to adopt their systems in the United States, while Morse, struggling to persuade his own countrymen of the merits of his system, although it was conceded by scientists to be the best, was unable to accomplish anything. He persisted in bringing the matter before congress after congress, until at last a bill granting him $30,000 was passed by the house on 23 Feb., 1842, by a majority of eight, the vote standing 90 to 82. On the last day of the session he left the capitol thoroughly disheartened, but found next morning that his bill had been rushed through the senate without division on the night of 3 March, 1843. There were yet many difficulties to be overcome, and with renewed energy he began to work. His intention was to place the wires in leaden pipes, buried in the earth. This proved impracticable, and other methods were devised. Ezra Cornell (q. v.) then became associated with him, and was charged with the laying of the wires, and after various accidents it was ultimately decided to suspend the wires, insulated, on poles in the air. These difficulties had not been considered, as it was supposed that the method of burying the wires, which had been adopted abroad, would prove successful. Nearly a year had been exhausted in making experiments, and the congressional appropriation was nearly consumed before the system of poles was resorted to. The construction of the line between Baltimore and Washington, a distance of about forty miles, was quickly accomplished, and on 11 May, 1844, Mr. Morse wrote to his assistant, Alfred Vail, in Baltimore, “Everything worked well.” Among the earliest messages, while the line was still in an experimental condition, was one from Baltimore announcing the nomination of Henry Clay to the presidency by the Whig convention in that city. The news was conveyed on the railroad to the nearest point that had been reached by the telegraph, and thence instantly transmitted over the wires to Washington. An hour later passengers arriving at Washington were surprised to find that the news had preceded them. By the end of the month communication between the two cities was complete, and practically perfect. The day that was chosen for the public exhibition was 24 May, 1844, when Mr. Morse invited his friends to assemble in the chamber of the U. S. supreme court, in the capitol, at Washington, while his assistant, Mr. Vail, was in Baltimore, at the Mount Claire depot. Miss Annie G. Ellsworth, daughter of Henry L. Ellsworth, then commissioner of patents, chose the words of the message. As she had been the first to announce to Mr. Morse the passage of the bill granting the appropriation to build the line, he had promised her this distinction. She selected the words “What hath God wrought,” taken from Numbers xxiii., 23. They were received at once by Mr. Vail, and sent back again in an instant. The strip of paper on which the telegraphic characters were printed was claimed by Gov. Thomas H. Seymour, of Connecticut, on the ground that Miss Ellsworth was a native of Hartford, and is now preserved in the archives by the Hartford athenæum. Two days later the national Democratic convention met in Baltimore and nominated James K. Polk for the presidency. Silas Wright, of New York, was then chosen for the vice-presidency, and the information was immediately conveyed by telegraph to Morse, and by him communicated to Mr. Wright, then in the senate chamber. A few minutes later the convention was astonished by receiving a telegram from Mr. Wright declining the nomination. The despatch was at once read before the convention, but the members were so incredulous that there was an adjournment to await the report of a committee that was sent to Washington to get reliable information on the subject.

|

Morse offered his telegraph to the U. S. government for $100,000, but, while $8,000 was voted for maintenance of the initial line, any further expenditure in that direction was declined. The patent then passed into private hands, and the Morse system became the property of a joint-stock company called the Magnetic telegraph company. Step by step, sometimes with rapid strides, but persistently, the telegraph spread over the United States, although not without accompanying difficulties. Morse's patents were violated, his honor disputed, and even his integrity was assailed, and rival companies devoured for a time all the profits of the business, but after a series of vexatious lawsuits his rights were affirmed by the U. S. supreme court. In 1846 he was granted an extension of his patent, and ultimately the Morse system was adopted in France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Russia, and Australia. The following statement, made in 1869 by the Western Union telegraph company, the largest corporation of its kind in the world, is still true: “Nearly all the machinery employed by the company belongs to the Morse system. This telegraph is now used almost exclusively everywhere, and the time will probably never come when it will cease to be the leading system of the world. Of more than a hundred devices that have been made to supersede it, not one has succeeded in accomplishing its purpose, and it is used at the present time upon more than ninety-five per cent of all the telegraph-lines in existence.” The establishment of the submarine telegraph is likewise due to Morse. In October, 1842, he made experiments with a cable between Castle Garden and Governor's island. The results were sufficient to show the practicability of such an undertaking. Later he held the office of electrician to the New York, Newfoundland, and London telegraph company, organized for the purpose of laying a cable across the Atlantic ocean. While in Paris during March, 1839, Morse met Daguerre, and became acquainted with his process of reproducing pictures by the action of sunlight on silver salts. He had previously experimented in the same lines while residing in New Haven, but without success. In June of the same year, after the French government had purchased the method from Daguerre, he communicated the details to Morse, who succeeded in acquiring the process, and was associated with John W. Draper (q. v.) in similar experiments. For some time afterward, until the telegraph absorbed his attention, he was engaged in experimenting toward the perfecting of the daguerreotype, and he shares with Prof. Draper the honor of being the first to make photographs of living persons. Morse also patented a machine for cutting marble in 1823, by which he hoped to be able to produce perfect copies of any model. In 1847 he purchased property on the east bank of the Hudson, near Poughkeepsie, which he called “Locust Grove,” where, after his marriage in 1848 to Sarah E. Griswold, he dispensed a generous hospitality, entertaining eminent artists and other notable persons. Soon afterward he bought a city residence on Twenty-second street, where he spent the winters, and on whose front since his death a marble tablet has been inserted, bearing the inscription, “In this house S. F. B. Morse lived for many years and died.”

He had many honors. Yale gave him the degree of LL. D. in 1846, and in 1842 the American institute gave him its gold medal for his experiments. In 1830 he was elected a corresponding member of the Historical institute of France, in 1837 a member of the Royal academy of fine arts in Belgium, in 1841 corresponding member of the National institution for the promotion of science in Washington, in 1845 corresponding member of the Archæological society of Belgium, in 1848 a member of the American philosophical society, and in 1849 a fellow of the American academy of arts and sciences. The sultan of Turkey presented him in 1848 with the decoration of Nishan Iftichar, or order of glory, set in diamonds. A golden snuff-box, containing the Prussian golden medal for scientific merit, was sent him in 1851; the great gold medal of arts and sciences was awarded him by Würtemberg in 1852, and in 1855 the emperor of Austria sent him the great gold medal of science and art. France made him a chevalier of the Legion of honor in 1856, Denmark conferred on him the cross of the order of the Dannebrog in 1856, Spain gave him the honor of knighthood and made him commander of the royal order of Isabella the Catholic in 1859, Portugal made him a knight of the tower and sword in 1860, and Italy conferred on him the insignia of chevalier of the royal order of Saints Lazaro Mauritio in 1864. In 1856 the telegraph companies of Great Britain gave him a banquet in London. At the instance of Napoleon III., emperor of the French, representatives of France, Austria, Sweden, Russia, Sardinia, the Netherlands, Turkey, Holland, the Papal States, and Tuscany, met in Paris during August, 1858, to decide upon a collective testimonial to Morse, and the result of their deliberations was a vote of 400,000 francs. During the same year the American colony of France entertained him at a dinner given in Paris, over which John S. Preston presided. On the occasion of his later visits to Europe he was received with great distinction. As he was returning from abroad in 1868 he received an invitation from his fellow-citizens, who united in saying: “Many of your fellow countrymen and numerous personal friends desire to give a definite expression of the fact that this country is in full accord with European nations in acknowledging your title to the position of the father of the modern telegraph, and at the same time in a fitting manner to welcome you to your home.” The day selected was 30 Dec., 1868, and Salmon P. Chase, chief justice of the U. S. supreme court, presided at the banquet in New York. On 10 June, 1871, he was further honored by the erection of a bronze statue of himself in Central park. Voluntary contributions had been gathered for two years from those who in various ways were connected with the electric telegraph. The statue is of heroic size, modelled by Byron M. Pickett, and represents Morse as holding the first message that was sent over the wires. In the evening of the same day a reception was held in the Academy of music, at which many eminent men of the nation were present. At the hour of nine the chairman announced that the telegraphic instrument before him, the original register employed in actual service, was connected with all the wires of the United States, and that the touch of the finger on the key would soon vibrate throughout the continent. The following message was then sent: “Greeting and thanks to the telegraph fraternity throughout the land. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good will to men.” At the last click of the instrument, Morse struck the sounder with his own name, amid the most extravagant applause. When the excitement had subsided, the chairman said: “Thus the father of the telegraph bids farewell to his children.” The last public service that he performed was the unveiling of the statue of Benjamin Franklin in Printing house square, on 17 Jan., 1872, in the presence of a vast number of citizens. He had cheerfully acceded to the request that he would perform this act, remarking that it would be his last. It was eminently appropriate that he should do this, for, as was said: “The one conducted the lightning safely from the sky; the other conducts it beneath the ocean, from continent to continent. The one tamed the lightning, the other makes it minister to human wants and human progress.” Shortly after his return to his home he was seized with neuralgia in his head, and after a few months of suffering he died. Memorial sessions of congress and of various state legislatures were held in his honor. “In person,” says his biographer, “Prof. Morse was tall, slender, graceful, and attractive. Six feet in stature, he stood erect and firm even in his old age. His blue eyes were expressive of genius and affection. His nature was a rare combination of solid intellect and delicate sensibility. Thoughtful, sober, and quiet, he readily entered into the enjoyments of domestic and social life, indulging in sallies of humor, and readily appreciating and enjoying the wit of others. Dignified in his intercourse with men, courteous and affable with the gentler sex, he was a good husband, a judicious father, a generous and faithful friend.” He was a ready writer, and, in addition to several controversial pamphlets concerning the telegraph, he published poems and articles in the “North American Review.” He edited the “Remains of Lucretia Maria Davidson” (New York, 1829), to which he added a personal memoir, and also published “Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States” (1835); “Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration, and the Present State of the Naturalization Laws, by an American,” originally contributed to the “Journal of Commerce” in 1835, and published anonymously in 1854; “Confessions of a French Catholic Priest, to which are added Warnings to the People of the United States, by the same Author” (edited and published with an introduction, 1837); and “Our Liberties defended, the Question discussed, Is the Protestant or Papal System most Favorable to Civil and Religious Liberty?” (1841). See “Life of Samuel F. B. Morse,” by Samuel Iremeus Prime (New York, 1875). — Another son of Jedidiah, Sidney Edwards, journalist, b. in Charlestown, Mass., 7 Feb., 1794; d. in New York city, 24 Dec., 1871, was graduated at Yale in 1811, and studied theology at Andover seminary, and law at the Litchfield, Conn., school. Meanwhile he became a contributor to the “Columbian Centinel” of Boston, writing a series of articles that illustrated the danger to the American Union from an undue multiplication of new states in the south, and showing that it would give to a sectional minority the control of the government. These led to his being invited by Jeremiah Evarts and others to found a weekly religious newspaper, to which he gave the name “Boston Recorder.” He continued as sole editor and proprietor of this journal for more than a year, and in this time raised its circulation until it was exceeded by that of only two Boston papers. Mr. Morse was then associated with his elder brother in patenting the flexible piston pump and extending its sale. In 1823 he came to New York, and with his brother, Richard C. Morse, founded the “New York Observer,” now the oldest weekly in New York city, and the oldest religious newspaper in the state. He continued as senior editor and proprietor until 1858, when he retired to private life. Mr. Morse in 1839 was associated with Henry A. Munson in the development of cerography, a method of printing maps in color on the common printing-press. He used this process to illustrate the geographical text-books that he published, and in early life he assisted his father in the preparation of works of that character. The last years of his life were devoted to experimenting with an invention for the rapid exploration of the depths of the sea. This instrument, called a bathyometer, was exhibited at the World's fair in Paris in 1869, and during 1870 in New York city. His publications include “A New System of Modern Geography” (Boston, 1823), of which more than half a million copies were sold; “Premium Questions on Slavery” (New York, 1860); “North American Atlas”; and “Cerographic Maps, comprising the Whole Field of Ancient and Modern, including Sacred, Geography, Chronology, and History.” — Another son, Richard Cary, journalist, b. in Charlestown, Mass., 18 June, 1795; d. in Kissingen, Bavaria, 23 Sept., 1868, was graduated at Yale in 1812, and spent the year following as amanuensis to President Timothy Dwight, with whose family he resided. He then entered Andover theological seminary, and after his graduation in 1817 was licensed to preach in the same year. During the winter of 1817-'18 he acted as supply to the Presbyterian church on John's island, S. C., and on his return to New Haven he assisted his father in the preparation of his geographical works. In 1823, with his brother, Sidney E. Morse, he established the “New York Observer,” of which he continued associate editor and part proprietor until his death, contributing largely to its columns, especially French and German translations. In 1858 he retired from active life, and in 1863 removed to New Haven, where he spent his last years.