Archaeological Journal/Volume 2/Notices of New Publications: The Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral

Notices of New Publications.

The high reputation of Professor Willis will suffer no diminution from the present work; on the contrary, the accurate research shewn in it, and the careful application of the information thereby acquired to the practical purpose of elucidating the history of this interesting Cathedral, would be sufficient to establish the reputation of an author previously unknown. It is not too much to say that we here have the first step towards a real history of architecture in England. Many attempts have indeed been previously made, and some of them with great pretension; an approximation to the truth has doubtless of late years been obtained, but no one hitherto has established the leading facts on the same firm and secure basis that we here find them fixed. Compared with this standard, all previous writers have been floundering in the dark, blind leaders of the blind; even the best informed differing strangely from each other as to the precise periods at which the principal changes took place, and no one feeling confidence in the results obtained from such uncertain premises. Professor Willis leaves no room for doubt: he demonstrates beyond all question every fact which he wishes to establish. It happens fortunately that the exact history of this celebrated building can be better ascertained from cotemporary authorities, than perhaps any other, and the acuteness with which the minute descriptions of Gervase and others are applied to the existing structure, is beyond all praise. After following the Professor in his comparison of the building itself with the details given by the chronicler, we feel that we can without hesitation affix a positive date to every stone of the church.

The work must become a standard of reference for all who wish to obtain accurate information on the very interesting subject of the progress of the art of building in England. It begins from the earliest period, and the first chapter relates "the history of the building, and the events which bore upon its construction, arrangement, and changes, in the words of the original authors as much as possible." The translation is remarkably close, and preserves all the spirit and life of the originals; those who had the pleasure of hearing that of Gervase read at the meeting at Canterbury, will not easily forget the thrilling effect which it produced, the rapturous manner with which it was received, or the clear and lucid explanations by which it was accompanied. The whole of these are here embodied, and the large diagrams which were hung over the Professor's head, and so often referred to in that interesting lecture, are here also presented to us and very clearly engraved, though on a small scale, with the date of the year when each part was built.

To those who were not fortunate enough to be present at the Canterbury Meeting, the following extracts will give some idea of the nature and value of the work. The earliest are from Edmer the singer, whose work is now in part first published from a manuscript in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

"A.D. 602.—When Augustine (the first archbishop of Canterbury) assumed the episcopal throne in that royal city, he recovered therein, by the king's assistance, a church which, as he was told, had been constructed by the original labour of Roman believers. This church he consecrated in the name of the Saviour, our God and Lord Jesus Christ; and there he established an habitation for himself, and for all his successors." p. 7. from Bede.

"A.D. 940 to 960.—In the days of Archbishop Odo (the twenty-second) the roof of Christ Church had become rotten from excessive age, and rested throughout upon half-shattered pieces: wherefore he set about to reconstruct it, and being also desirous of giving to the walls a more aspiring altitude, he directed his assembled workmen to remove altogether the disjointed structure above, and commanded them to supply the deficient height of the walls by raising them." p. 3. from Edmer.

"A.D. 1011.—In the primacy of Archbishop Elphege (the twenty-eighth) the sack of Canterbury by the Danes took place. During the massacre of the inhabitants, the monks barricaded themselves in the church. The archbishop at length rushed out, and appealed in vain to the conquerors, in favour of the people: he was immediately seized, and dragged back to the churchyard. 'Here these children of Satan piled barrels one upon another, and set them on fire, designing thus to burn the roof. Already the heat of the flames began to melt the lead, which ran down inside, when the monks came forth,' and submitted to their fate: four only of their number escaped slaughter. 'And now that the people were slain, the city burnt, and the church profaned, searched and despoiled,' the archbishop was led away bound, and, after enduring imprisonment and torture for seven months, was finally slain." p. 7. from Osbern.

"It must be remarked, however, that the church itself at the time of the suffering of the blessed martyr Elphege, was neither consumed by the fire, nor were its walls or its roof destroyed. "We know indeed that it was profaned and despoiled of many of its ornaments, and that the furious band attacked it, and applied fire from without to drive out the pontiff" who was defending himself inside. But when they had laid hands upon him on his coming forth, they abandoned their fire, and other evil deeds which were addressed to his capture, and after slaying his monks before his eyes, they carried him away."

"A.D. 1067.—After these things, and while misfortunes fell thick upon all parts of England, it happened that the city of Canterbury was set on fire by the carelessness of some individuals, and that the rising flames caught the mother church thereof. How can I tell it?—the whole was consumed, and nearly all the monastic offices that appertained to it, as well as the church of the blessed John the Baptist, where the remains of the archbishops were buried." p. 9. from Edmer.

"This was that very church (asking patience for a digression) which had been built by Romans, as Bede bears witness in his history, and which was duly arranged in some parts in imitation of the church of the blessed Prince of the Apostles, Peter; in which his holy relics are exalted by the veneration of the whole world." p. 10. from Edmer, and quoted by Gervase.

Of this Saxon church we are then furnished with a full description, accompanied by a ground plan, and for the sake of comparison a plan also of the ancient basilica of St. Peter at Rome, from which the design had been copied; but of this church it is clearly established that not a vestige now remains, and it is important to bear this in mind when comparing the history of other buildings with the severe test of Canterbury.

"Now, after this lamentable fire, the bodies of the pontiffs (namely, Cuthbert, Bregwin, and their successors) rested undisturbed in their coffins for three years, until that most energetic and honourable man, Lanfranc, abbot of Caen, was made archbishop of Canterbury. And when he came to Canterbury, (A.D. 1070,) and found that the church of the Saviour, which he had undertaken to rule, was reduced to almost nothing by fire and ruin, he was filled with consternation. But although the magnitude of the damage had well nigh reduced him to despair, he took courage, and neglecting his own accommodation, he completed, in all haste, the houses essential to the monks. For those which had been used for many years were found too small for the increased numbers of the convent. He therefore pulled down to the ground all that he found of the burnt monastery, whether of buildings or the wasted remains of buildings, and, having dug out their foundations from under the earth, he constructed in their stead others, which excelled them greatly both in beauty and magnitude. He built cloisters, cellerers' offices, refectories, dormitories, with all other necessary offices, and all the buildings within the enclosure of the curia, as well as the walls thereof. As for the church, which the aforesaid fire, combined with its age, had rendered completely unserviceable, he set about to destroy it utterly, and erect a more noble one. And in the space of seven years, he raised this new church from the very foundations, and rendered it nearly perfect." p. 14. from Edmer.

"After the death of Lanfranc, he (Ernulf) was made prior, then (in 1107) abbot of Burgh, (Peterborough,) and finally, (A.D. 1114,) bishop of Rochester. While at Canterbury, having taken down the eastern part of the church which Lanfranc had built, he erected it so much more magnificently, that nothing like it could be seen in England, either for the brilliancy of its glass windows, the beauty of its marble pavement, or the many coloured pictures which led the wondering eyes to the very summit of the ceiling." p. 17. from Will. Malms.

"This chancel, however, which Ernulf left unfinished, was superbly completed by his successor Conrad, who decorated it with excellent paintings, and furnished it with precious ornaments." p. 17.

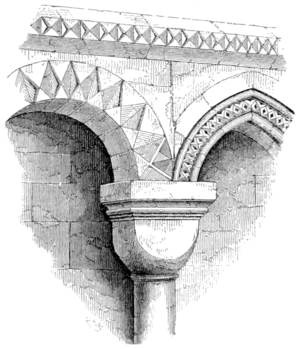

The oldest portions of the cathedral now standing are therefore of the time of Lanfranc, and of this period little more than a few fragments remain; the principal part of the old work previous to the great fire is the work of Ernulf and Conrad; the distinct character of this early Norman work is admirably brought out and contrasted with the late Norman and Transition work after the fire; this is well shewn in the annexed cut of part of the crypt, where the pillar had been introduced after the fire, the plan of the superstructure not being the same as that of the ancient crypt, so that additional strength was required to carry the weight in its new position. But the words of Gervase are so explicit that there is no need to add to them.

"It has been above stated, that after the fire nearly all the old portions of the choir were destroyed and changed into somewhat new and of a more noble fashion. The differences between the two works may now be enumerated. The pillars of the old and new work are alike in form and thickness but different in length. For the new pillars were elongated by almost twelve feet. In the old capitals the work was plain, in the new ones exquisite in sculpture. There the circuit of the choir had twenty-two pillars, here are twenty-eight. There the arches and every thing else was plain, or sculptured with an axe and not with a chisel. But here almost throughout is appropriate sculpture. No marble columns were there, but here are innumerable ones. There, in the circuit around the choir, the vaults were plain, but here they are arch-ribbed and have keystones. There a wall set upon pillars divided the crosses from the choir, but here the crosses are separated from the choir by no such partition, and converge together in one keystone, which is placed in the middle of the great vault which rests on the four principal pillars. There, there was a ceiling of wood decorated with excellent painting, but here is a vault beautifully constructed of stone and light tufa. There, was a single triforium, but here are two in the choir and a third in the aisle of the church. All which will be better understood from inspection than by any description." pp. 58—60, from Gervase."The capitals of the columns of the crypt are either plain blocks or sculptured with Norman enrichments. Some of them, however, are in an unfinished state. These figures represent one of the columns with the different sides of its capital." p. 69.

"Of the four sides of the block two are quite plain, as at A. One (as B) has the ornament roughed out, or "bosted" as the workmen call it, that is, the pattern has been traced upon the block, and the spaces between the figures roughly sunk down with square edges preparatory to the completion. On the fourth side, as at C, the pattern is quite finished. This proves that the carving was executed after the stones were set in their places, and probably the whole of these capitals would eventually have been so ornamented had not the fire and its results brought in a new school of carving in the rich foliated capitals, which caused this merely superficial method of decoration to be neglected and abandoned. In the same way some of the shafts are roughly fluted in various fashions. The figure shews one of them, and the plain ones would probably have all gradually had the same ornament given to them, had not the same reasons interfered." p. 70.

The vivid and minute description of the great fire by Gervase, is literally translated in a manner which leaves nothing to be desired.

"In the year of grace one thousand one hundred and seventy-four, by the just but occult judgment of God, the church of Christ at Canterbury was consumed by fire, in the forty-fourth year from its dedication, that glorious choir, to wit, which had been so magnificently completed by the care and industry of Prior Conrad." p. 32.

"Meantime the three cottages, whence the mischief had arisen, being destroyed, and the popular excitement having subsided, everybody went home again, while the neglected church was consuming with internal fire unknown to all. But beams and braces burning, the flames rose to the slopes of the roof; and the sheets of lead yielded to the increasing heat and began to melt. Thus the raging wind, finding a freer entrance, increased the fury of the fire; and the flames beginning to shew themselves, a cry arose in the church-yard: 'See! see! the church is on fire.'

"Then the people and the monks assemble in haste, they draw water, they brandish their hatchets, they run up the stairs, full of eagerness to save the church, already, alas! beyond their help. But when they reach the roof and perceive the black smoke and scorching flames that pervade it throughout, they abandon the attempt in despair, and thinking only of their own safety, make all haste to descend.

"And now that the fire had loosened the beams from the pegs that bound them together, the half-burnt timbers fell into the choir below upon the seats of the monks; the seats, consisting of a great mass of wood-work, caught fire, and thus the mischief grew worse and worse. And it was marvellous, though sad, to behold how that glorious choir itself fed and assisted the fire that was destroying it. For the flames multiplied by this mass of timber, and extending upwards full fifteen cubits, scorched and burnt the walls, and more especially injured the columns of the church." p. 33.

After the fire "the brotherhood sought counsel as to how and in what manner the burnt church might be repaired, but without success; for the columns of the church, commonly termed the pillars, were exceedingly weakened by the heat of the fire, and were scaling in pieces and hardly able to stand, so that they frightened even the wisest out of their wits.

"French and English artificers were therefore summoned, but even these differed in opinion. On the one hand, some undertook to repair the aforesaid columns without mischief to the walls above. On the other hand, there were some who asserted that the whole church must be pulled down if the monks wished to exist in safety. This opinion, true as it was, excruciated the monks with grief, and no wonder, for how could they hope that so great a work should be completed in their days by any human ingenuity.

"However, amongst the other workmen there had come a certain William of Sens, a man active and ready, and as a workman most skilful both in wood and stone. Him, therefore, they retained, on account of his lively genius and good reputation, and dismissed the others. And to him, and to the providence of God was the execution of the work committed." p. 35.

Gervase goes on to describe the church of Lanfranc and the choir of Conrad, and to compare them with the new work, by which means we are now enabled to identify all that still exists of the earlier work. He afterwards describes the operations of each successive year of the construction of the new work, and here the skill of his translator and annotator is eminently shewn in applying his descriptions, and thus enabling us to identify in the existing structure the work of each year from 1175 to 1184. It is not a little remarkable that the earlier work partakes much more of the Norman character; thus the work of 1175 is pure Norman, with the exception only of the pointed arch, while in 1184, after having traced the progressive change, we have in the Trinity chapel and the corona almost pure Early English work. It must be remembered that in 1178 William of Sens was so much injured by the fall of a scaffold on which he was at work, at the height of fifty feet from the ground, that he was unable to continue the work.

"And the master, perceiving that he derived no benefit from the physicians, gave up the work, and crossing the sea, returned to his home in France. And another succeeded him in the charge of the works; William by name. English by nation, small in body, but in workmanship of many kinds acute and honest." p. 51.

The Early English work is therefore the work of William the Englishman, not of William of Sens; this may be accidental, but the main point is clearly established, that it was at this precise period the great change of style took place in England, and we may fairly assume in France also, since it is hardly possible that if the new style was known in France at the time William of Sens came over, he would be ignorant of it, and if acquainted with it, he would certainly have adopted it at once in his new work, instead of leaving it to be fully developed by his successor.

The subsequent history of the cathedral is perhaps less interesting, but every period is made out with equal clearness from the Registers and other documents; for instance, "'Anno 1304 and 5. Reparation of the whole choir with three new doors, a new screen or rood-loft, (pulpitum,) and the reparation of the chapter-house with two new gables . . . . 839l. 7s. 8d.' These entries must refer to the beautiful stone enclosure of the choir, the greatest part of which still remains. The three doors are the central or western one, and the north and south doors." p. 97.

The elegant diaper-work on the south side of the choir near the high Altar is supposed to have been part of St. Dunstan's shrine, and probably also the work of De Estria.

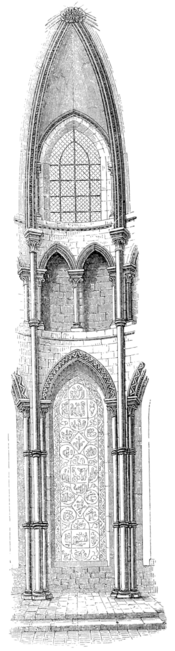

The fine decorated window in St. Anselm's chapel, said to have been erected in 1336, of which the bill is printed from the archives, bears so close a resemblance to the east window of Chartham church, a few miles only from Canterbury, that it must be considered as the work of the same hand, Henry de Estria, but as he died in 1331 there must be some error in the date of this window, which certainly looks earlier than 1336.

"The Nave.—In December of the year 1378, Archbishop Sudbury issued a mandate addressed to all ecclesiastical persons in his diocese en- joining them to solicit subscriptions for rebuilding the nave of the church, and granting forty days' indulgence to all contributors. The preamble states that the nave, on account of its notorious and evident state of ruin, must necessarily be totally rebuilt, that the work was already begun, and that funds were wanting to complete it." p. 117.

"A.D. 1381-96.—In the Obituary it is recorded that Archbishop Courtney gave more than a thousand marks to the fabric of the nave of the church, the cloister, &c.; and that Archbishop Arundell (A.D. 1396-1413.) gave five sweet sounding bells, commonly called 'Arundell ryng,' as well as a thousand marks to the fabric of the nave." p. 118.

"A.D. 1390-1411.—Of Prior Chillenden, the same document states that 'he, by the help and assistance of the Rev. Father Thomas Arundell, did entirely rebuild the nave of the church, together with the chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary, therein situated, and handsomely constructed.' Also the cloister, chapter-house, and other buildings enumerated.

"The epitaph of this prior, preserved by Somner, confirms this statement, by saying, 'Here lieth Thomas Chyllendenne, formerly Prior of this Church . . . who reconstructed the nave of the Church and divers other buildings . . . and who, after holding the priorate twenty years, twenty-five weeks, and five days, completed his last day on the assumption of the Blessed Virgin, (Aug. 25) A.D. 1411.'" p. 119.

"The Lady Chapel, south-west Tower, and Chapel of St. Michael.—The Obituary records of Prior Goldston, (A.D. 1449-68,) that 'he built on the north side of the church a chapel in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in which he was buried. He completely finished this chapel, with a stone vault of most artificial construction, a leaden roof, glass windows, and all other things belonging to it. He also constructed the walls of the courtyard, 'atrium,' of the said chapel, with a lead roof but no vault."—'Moreover, he finished with beautiful workmanship the tower or campanile which was on the south part of the nave; from the height of the side-aisle of the church upward.'" p. 123.

"The central Tower, or Angel Steeple.—(A.D. 1495-1517.)—In the year 1495 Prior Sellyng was succeeded by a second Thomas Goldston, who like his namesake was a great builder, and the Obituary records many works of his. But that which he added to the church will be best stated in the exact words of the original.

"'He by the influence and help of those honourable men. Cardinal John Morton and Prior William Sellyng, erected and magnificently completed that lofty tower commonly called Angell Stepyll in the midst of the church, between the choir and the nave,—vaulted with a most beautiful vault, and with excellent and artistic workmanship in every part sculptured and gilt, with ample windows glazed and ironed. He also with great care and industry annexed to the columns which support the same tower, two arches or vaults of stone work, curiously carved, and four smaller ones, to assist in sustaining the said tower.'" p. 126.

We cannot take leave of the learned Professor and his interesting work without expressing a confident hope that he will continue thus to give the Institute the benefit of his talents and researches, and to allow the world to profit by them afterwards in a similar manner.