Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/Antiquities Found at Woodperry, Oxon

ANTIQUITIES FOUND AT WOODPERRY, OXON.

Woodperry[1], a hamlet or tithing of the parish of Stanton St. John, in the neighbourhood of Oxford, appears, by the numerous antiquities of many periods there discovered, to have been a place of popular resort by successive races from the earliest times, until the church and village, as traditionally reported, were totally destroyed by a conflagration. The neighbourhood abounds with Roman remains, amongst which may be included the newly discovered villa at Wheatley, described in No. 8 of the Journal; and at the distance of about half a mile ran the line of the great road between Eboracum and Clausentum, given in the 18th iter of Ricardus Corinensis, a portion of which has been ably illustrated by Mr. Hussey[2]; but there was no suspicion of any thing Roman existing on this particular spot, until the discovery chanced to take place, in the course of a different, though not less interesting inquiry, the search for a church, churchyard, and village, supposed to have formerly existed there. As far as regards the objects for which they were made, these researches were completely successful, establishing the fact of the existence of a church, and cemetery around it; disclosing also some little remaining portion of the foundation of the former, with fragments of the edifice itself, uninscribed monumental stones, and encaustic tiles, nearly all of which would afford probable conjectures as to dates; while the colour and nature of the soil shewed with tolerable accuracy how far the building had extended. Around, and without it, the number of bodies, and their regular position, left no doubt as to the existence of a churchyard; while lower down in the field, the remains of buildings scattered thickly over part of it, and entering into a little close below, which itself reaches up to the Horton road, and the change visible in the quality of the soil, here naturally a cold clay, into a rich black mould of some depth, afforded convincing proofs of long continued inhabitancy. But amongst the discoveries which the spade brought to light, not the least unlooked for and curious was the fact, that the Romans had been amongst the original occupants of the spot, as was abundantly proved by the remains of their pottery in endless varieties, fragments of vessels, cinerary urns, trinkets, and coins found here. There were also evidences of what may be called a transition state; for the inhabitants of a later period had pounded the red and thick Roman tiles, appearing here in very great quantities, and worked them up with lime for their new building. These remains, it should be observed, were principally discovered, not on the site of the church, but amongst the scattered ruins of the village.

There is a passage in Hearne's Diaries, now preserved in the Bodleian Library, which is valuable as describing the state of the place in his time. He is writing on Nov. 15, 1732[3]. "One Mr. Mendi," he says, "a Joyner, a good cleaver Workman, who works at Woodbury Farm by Beckley, told me last night of Foundations of old buildings, frequently dug up there, and that there is a Tradition that there hath been a Town there. He said an earthen Pot was sometime since found there, but that 'twas broke, and nothing found in it but ashes and dust and one silver piece. From his account I took the said piece to be a Roman Denarius, and the Vessel to be an urn, and indeed there was a Branch of a Roman Way came along this way on the East side of Stowe Wood[4]. The Foundations they find are of Stone, strangely rivetted into the roots of Trees sometimes.

"Woodbury belongs to one Mr. Morse, who hath built a new House there. He is a single man, a batchelor, about 74 years of age. He is reported to be worth three hundred thousand pounds. He hath estates in other places, and is still purchasing others."

The result of subsequent researches has confirmed the probability of Hearne's conjecture as to what the earthen pot and coin really might have been: but it is much to be regretted, that, with very few exceptions, all objects of a fragile nature found upon this spot of late years have been broken into pieces, and these again dispersed. The cause, whatever it was, and whether an accidental fire, (as is reported,) or not, which brought destruction upon the church and village, can hardly be supposed to have effected this; it must be owing to subsequent digging amongst, and removal of, the ruins. No cottages, it is true, have sprung up to supply the place of those which once stood here; but the "new House" which Hearne mentions to have been built by a Mr. Morse, remains, and has a very considerable extent of stone wall running round the kitchen garden and pleasure grounds attached to it, which adjoin the ruins, and the materials of these not improbably may have been borrowed from "the old Town." The trees have in a great degree disappeared, and in their removal would occasion the displacement of other stones beneath those "strangely rivetted into the roots;" while in later years re- course has been had to this spot as a general quarry for supplying materials for the roads and other purposes; so that it is no wonder if in turning over the stones, in order to select the largest and best, and in digging down for the same object, any weaker substance lying amongst them should have been injured or crushed.

Amongst the very few fictile articles which had wholly escaped damage was an earthen pan, (literally such,) found nearly above the spot where the Altar may be supposed to have stood, and carefully covered over with a piece of ashlar stone: it was a little injured by the workman's pick-axe, but the situation, the size, and evident care with which it had been deposited, caused much to be expected from the contents; yet upon removing the covering they were found to be nothing but earth; neither was there the slightest reason, as far as could be judged, to suspect any dishonesty on the part of those who had discovered it.

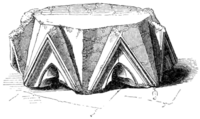

The pan was turned in a lathe, of very thin red ware, not glazed, except at the bottom of the inside, similar in shape to those now in common use, and strengthened externally towards the upper rim by nine ornaments of a fillet pattern, running upwards at equal intervals, with a greater projection towards the top, but dying into the substance of the vessel at about one third from its bottom. The diameter of the top of the pan was 1512 inches, of the bottom 1034, and the depth 812. The stone which covered it was 1512 inches by 1412, and 312 thick.

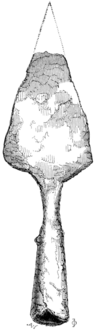

| Figs. 2, 3. Iron Arrow-heads. | |

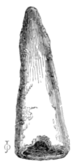

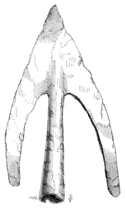

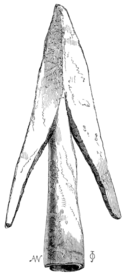

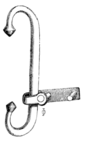

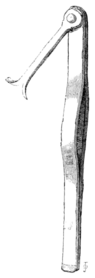

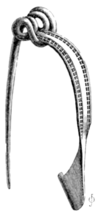

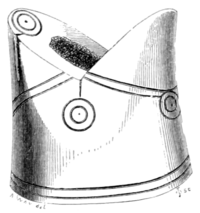

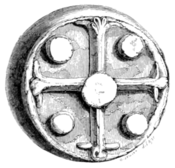

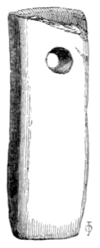

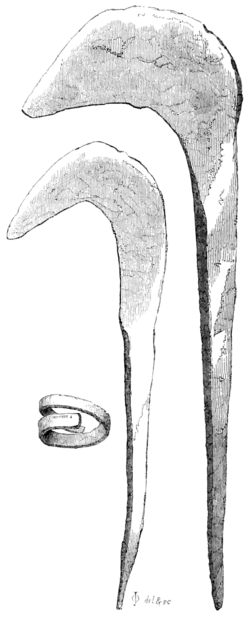

Arrow-heads of considerable variety in form and dimension, have from time to time been found at Woodperry (fig. 1.) Amongst them may be noticed one of simple conical shape, measuring in length 134 inches; it was formed of bone, and rudely ornamented with incised lines, crossing each other fret-wise. Two similar arrow or bolt-heads formed of iron (figs. 2, 3), tapering gradually to a blunt point, were also discovered, and other examples of the same metal, Bone Arrow head. some fashioned with a flat triangular blade (fig. 4), not barbed, and others furnished with barbs of unusual length (figs. 5, 6, 7), in one instance measuring about 134 inches[5]. Several large

(Figs. 4, 5, 6) Iron Arrow heads | |||

signaculum of lead, on which is the inscription, AVE MARIA GRA (fig. 17). Several small vessels of earthenware have been found at Woodperry, which may be regarded as curious examples of medieval date; the ware being wholly distinct from the remains of "Samian," or Anglo-Roman fabrication, of which beautifully ornamented fragments have occurred; and some even superior, though in the same style of ornament, were discovered by the late Sir Alexander Croke, nearly six or seven years since, in the middle of a wood, now called "the New Wood," on the brow of the opposite hill, about a mile distant; but these excavations were not pursued so far as might have been desired, and the traces of buildings were in fact but faint and inconsiderable. A very common form of these medieval vessels will be found represented in the plate, page 62 of No. 9 of the Journal, being that of the two smallest of the four, though the neck in general is somewhat narrower. Very many fragments of them occur, and of different sizes, the ordinary height being about six inches, as near as can be guessed from the more perfect specimens: it is, however, to be observed of all, that they are tinted with green colour and slightly glazed, immediately below the neck. Of pottery, however, really Anglo-Roman, the varieties were very many, especially of the finest or Samian ware; for beginning with that on which figures had been worked in relief, fragments of plain pateræ were turned up of almost every degree of fineness, the best being composed of a highly coloured red clay, and other specimens presenting a fainter and fainter hue, precisely in proportion to their goodness, the palest being always the worst. Still, in every case, the clay had been admirably well tempered; and it should be observed, by the way, that what is found at Brill, between four and five miles distant, is considered to be of excellent quality, and this had probably been procured from that quarter. Be this, however, as it may, there certainly was a Roman pottery five or six miles to the north, at Fencot upon Otmoor[6]; and if that situation did not offer the very finest materials, the establishment at least gave the opportunity of baking vessels which had been manufactured from better clay found elsewhere. In addition to what may be called, by way of distinction, the red ware, other fragments of pottery discovered, presented a great variety of form and pattern, and indeed it may be almost added, of material. Very many were of dusky blueish hue, supposed to be produced by some process in the burning; some coarse, thick and pale, and painted internally in concentric circles of a red colour; others, on the contrary, very thin, dark, and glazed on the outside, and elegantly marked, as if with a graving tool, something in the style of a British urn, only infinitely better. Fragments of a cinerary urn were found, (such an one probably as Hearne's earthen pot), pieces of which being observed to correspond, have since been cemented together, and are sufficient to give an idea of what it must have been, when perfect. It appears to have borne in some degree the shape of that engraved in Tab. xv. No. 24. of Plot's Oxfordshire, but had no foot, and stood on a plain bottom, which was not less than ten inches in diameter: the height, perhaps, was nearly the same, and the mouth seven or eight inches across. It was thin, but strong; visibly marked on the outside by the action of flame, and contained red earth or ashes, mixed with many pieces of some white substance, perhaps bone, all of which had obviously been burnt. Fragments of Roman tiles, of all kinds, were very numerous; none of them, indeed, in situ, as they were set by the mason, but some had still mortar adhering to them; and in one spot were the traces of a circular furnace or fireplace, about four feet in diameter, which might have been used for supplying hot air to apartments. Not far above it was a well in good preservation, about twenty feet deep; which being cleared out, afforded nothing more interesting than the bones of many horses and dogs; and lower again, was a smith's shop, as was conjectured from a heap of cinders and many keys found there. Mixed up with other remains were bones and antlers of deer, horns of oxen, bones of pigs, portions of vessels turned in stone, a stone much broken appearing to have belonged to a hand-mill, and frequent fragments of iron slag, or the refuse of an iron foundry; a substance also observed at Drunshill, near Woodeaton, in the neighbourhood[7], where again the Romans have been, as is attested by many remains of their pottery, and by a brass coin of Vespasian, in good preservation, which was picked up there in 1841. The coins found at Woodperry have been nearly all in second, with one or two in third, brass ; and were of Domitian, Hadrian, Diocletian, Maximian, Constantine, and Claudius Gothicus. A second brass of Nero was discovered in the beginning of 1842, in a ploughed field called Upper Stafford Grove[8], near the line of the Roman road, the stones of which, the farmer, with little reverence for antiquity, was then removing. During the continuance of the same operation, and not far from the same spot, scarcely a foot under the surface of the ground, the labourers came upon a human skeleton. It lay parallel to the Roman road, about forty yards from it, and was deposited north and south, the head towards the south, but presented nothing remarkable either in size or otherwise, being that of a person of low stature.

In this part of the subject it should be mentioned, as connected with the neighbourhood, that a silver coin of the gens Plautia was picked up near a footpath, in an adjoining parish, a few months since; and very lately, a third brass of Constantine, not far from the course of the Roman road through Beckley. Holton has afforded many specimens; but the greatest discovery was made at Shotover, upon the estate of G. V. Drury, Esq., in the month of May, 1842, when 560 coins were at once disclosed by the wheel of a waggon breaking the pot in which they had been deposited. They were given up to the proprietor.

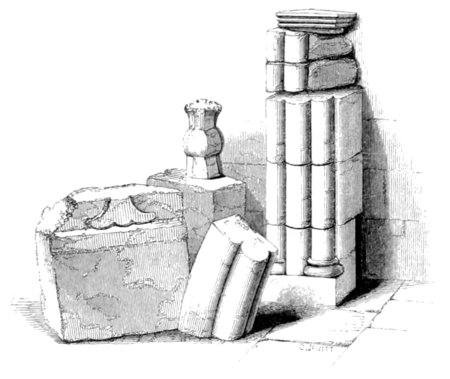

The consideration of ecclesiastical remains may not be thought to belong so properly to our pages as to a work dedicated expressly to that subject[9], but having been favoured with the use of the plates, some few notices respecting the objects they represent may not be unacceptable.

Woodperry, now a hamlet of Stanton St. John, as has been already stated, appears originally to have been a distinct, though small, parish. By what means or at what period it became united to its neighbour, is unknown, nor have the records of the diocese of Lincoln, within which it was once comprised, thrown any light upon the point. It is usual to commence topographical inquiries by a reference to the Norman Survey; and a conjecture has been advanced that Woodperry may be found noticed in that record under the designation of PEREGIE, holden by Rogerius of the bishop of Bayeux[10], Waterperry being admitted to be described as PEREIVN. One reason for this idea, and that of but little weight, is, that Peregie occurs immediately after the mention of Fostel or Forest-hill; it may be more to the purpose to observe, that the quantity of land (four hides) stated in Domesday Book, agrees with that assigned to Woodperry at a later period in the Rotuli Hundredorum[11]; there is also the indirect proof, that PEREGIE has been attributed to no other place. Forming a member of the honor of S. Walery, within which Stanton St. John was not included, it was holden in capite by Richard earl of Cornwall, and afterwards king of the Romans, by the service of one knight's fee, Roger d'Aumari being sometime his tenant[12]. From Richard the honor descended to his son Edmund; and on the death of the latter without issue in 1300, his manors, &c., fell to the crown; when, in the very first year of his reign, Edward II. granted the whole earldom of Cornwall (Woodperry included) to Piers Gaveston. On the death of the latter, the property reverting, was immediately granted again in 1312, to a new favourite, Hugh Despencer the elder; on whose attainder, in 1326, it came again into the royal hands.

In 1330 Edward III. granted the honor of S. Walery, including Woodperry, to his next brother John de Eltham, whom he had previously advanced to the earldom of Cornwall. He too dying without issue, the same king in 1360 granted the manor of Wodepery to his faithful soldier John, or Sir John, Chandos. He also perished childless in the wars in France; and what became of the estate does not clearly appear, until at the beginning of the sixteenth century, it came by purchase into the hands of its present owners.

One purpose of the above notices has been to throw some little light upon the architectural history of the church. The fragments found present an extraordinary variety of dates; for, beginning with part of the arch of a Norman doorway, they terminate in a fragment of the square head- moulding of a door or window in a style apparently that of the 14th century, or possibly much later. If then the first-mentioned arch, joined with the fact of Richard's armorial bearings as earl of Poictou, (a lion rampant crowned,) and as king of the Romans, (the spread eagle,) being found depicted on the encaustic tiles, would afford a plausible conjecture as to the time the building was erected,—on the other hand, the style of the fragment of moulding, compared with Hearne's report in 1732, that there was a tradition, and a tradition only, all remembrance being lost, "that there had been once a town here," over which he describes timber trees then to grow, would give us limits, and not very wide ones, for the period of its destruction.The abbat and canons of Oseney had a portion of tithes here, small indeed, as being worth at the Dissolution only 10s. per annum, but sufficient to give them an interest in the place, and justify their application to Richard, or a less wealthy proprietor, for assistance in raising the house of God. And as no traces of an established ecclesiastical benefice appear, it is probable that the cure was served, as was not unusual, by members of their house; and that those who rest under the three tombstones, yet remaining within the limits of the walls of the edifice, may have been chaplains who ended their days in the performance of their duties on the spot.

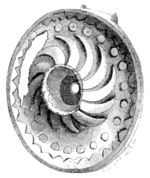

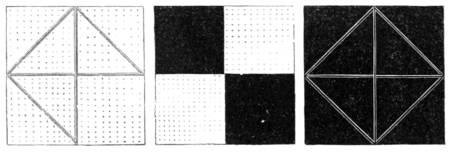

It should be observed that the greater part of the encaustic pavement was not set as before an altar, but between the tombstones represented; many smaller fragments being found dispersed. It had on the east side a border of similar tiles, each 5 inches square, and marked checquer-wise across the middle, so as to form four divisions, which were coloured alternately yellow and black, or very deep brown. The effect was by no means pleasing; but it is a curious fact, that the same border is found represented on some painted glass, known from several circumstances to be of very high antiquity, now placed in the church of Rivenhall, Essex. It was purchased from a church near Lisieux in Normandy, and fixed where it may be seen at present, at the expense of the Rev. Bradford Hawkins, curate of the parish.

The intersecting and diagonal lines do not seem to be merely ornamental, but were made before the tile was burnt, for the purpose, it is supposed, of enabling the mason to break off with his trowel certain portions of a prescribed shape.

J. W. - ↑ This name is so spelt in conformity with the modern usage and pronunciation; but the earlier forms give Wodehury, pire, pery, &c., with one R, which is the case also with Waterpery, a village not far distant.

- ↑ An account of the Roman road from Allchester to Dorchester, by the Rev. Robert Hussey, B.D., 8vo. 1841, Oxford, for the Ashmolean Society.

- ↑ Vol. 137, pp. 99, 100.

- ↑ Hearne is wrong here; not in the course of the road, but in calling it a branch, since it was the main line from Eboracum mentioned before. No one, however, from its appearance would conjecture it to becmore than a diverticulum; and the work of Richard, from which only we learn its extent and importance, was not printed until 1757, nor known long before.

- ↑ In the armoury at Goodrich Court are preserved two iron piles of arrows, with four-sided points, and an "unique specimen of the ancient British arrow," discovered at the base of Clifford's Tower, York, the head resembling in form one of those which were found at Woodperry. Sir Samuel Meyrick considers this missile as having been used during the wars of the Roses. Skelton's Goodrich Armoury, I. pl. xvi, xxxiv.

- ↑ See Mr. Hussey's Roman Road, already quoted, p. 34.

- ↑ Mr. Hussey's R. Road, pp. 38, 39, 40.

- ↑ Mr. Hussey's R. Road, pp. 11, 12.

- ↑ Guide to the Architectural Antiquities in the Neighbourhood of Oxford.

- ↑ Fol. 156. a.

- ↑ Vol. ii. 38.

- ↑ Rott. Hundd., ii. 39, 717.