Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/On some Anomalies observable in the Earlier styles of English Architecture

THE

Archaeological Journal.

DECEMBER, 1846.

ON SOME ANOMALIES OBSERVABLE IN THE EARLIER

STYLES OF ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE.

It has been usual with those who have made enquiries into the style of our early ecclesiastical buildings, to assign all those exhibiting marks of long and short work to the period of the Anglo-Saxons. Yet it may be reasonably doubted whether construction of this nature, taken by itself, affords sufficient evidence to favour such conclusions: and unless this kind of masonry be found united with proofs of another character less ambiguous, there is great room for disbelieving such buildings to have been erected before the Norman Conquest.

It is indeed not a little remarkable that the church of Brixworth, a building whose claims to priority of age are better established than most others by historical inference, is entirely deficient in the marks so universally assumed to be decisive of the question.

This church, as it is well known, does not shew the least fragment of this peculiar kind of construction, yet there is perhaps more extrinsic evidence in favour of its age, than most other buildings that can be adduced. The history of its erection seems simply to have been this, that from its scite having been fixed upon close to a great Roman thoroughfare leading from the Watling Street, at Stoney Stratford, through Northampton to Leicester, as is sufficiently indicated by the direct trending of the line, and the etymologies of the places bordering upon it, such as, Potterspurry, Alderton, Barrow Dykes, Lamport, Market Harboro', Stonyland, Stony Gate, &c.; and also being on the very edge of a Roman single walled entrenchment, there were already on the spot most of the materials which the Romans themselves had used for building purposes. Within this entrenchment, some kind of building had existed, and the bricks that were employed were found, when the church was in progress of erection, extremely useful to work up with the bad materials already dug. We are told by William of Malmesbury, that Benedict Bishop on his return from Rome introduced a new kind of architecture into this country, what he calls building more Romano; now in whatever sense these two words are interpreted, I think they will still be applicable to the masonry of Brixworth church, and this, coupled with the casual passage quoted in Leland's Itinerary, will go very far to confirm its Anglo-Saxon pretensions; in fact it is more evidence of an early practical kind than can be brought to bear upon any other building of a Christian character in England.

It is now some years since I became entirely convinced that Brixworth church presented no proof whatever of being a Roman building. I have examined its foundations, its construction, and the nature of its cements, all of which are totally unlike the substructions, the masonry, and the mortar so invariably adopted by the Romans.

Whilst, however, its Roman claims are completely untenable, it certainly offers very strong marks in favour of an Anglo-Saxon origin. They are not only as convincing as any we may ever hope to obtain elsewhere, but they are moreover capable of being divided into two periods.

It has already been stated that Brixworth does not present any specimen of long and short work; this peculiarity is not visible in any portion of the building. It is desirable to state this distinctly, because having presumptive historical evidence of being an Anglo-Saxon church, it is deficient in that feature which is accounted the leading characteristic of Anglo-Saxon architecture.

It is not my intention to disprove (for that would be a difficult matter) the title to great antiquity those churches may claim, where long and short coignings are used, but I wish to throw out a caution to enquirers, lest this appearance should lead them to assign all these buildings to the same age.

That they are for the most part early structures there can be no doubt, and this epithet may be even extended above the Norman Conquest, if we are justified in applying the words lapidei tabulatus, as used by William of Malmesbury in his description of Benedict Bishop's churches, to those towers rising in stages from the perpent blocks of stone that run transversely on their four sides.

For instance, at Earl's Barton and Barnack this system occurs, at both of which places the towers rise in stages, diminishing as they rise, and forming separate divisions or stories, marked also by the horizontal bands of perpent stone, from which the superior portions of the building alternately spring.

This mode of construction was clearly borrowed from the Romans, who, as is sufficiently known, employed bonding courses of brick, running parallel with the ground, to strengthen their walls, so that the inferior materials used in the intervening space might become more effectually tied together.

The Romans, as may be observed in all their military buildings now remaining in England, used their bonding courses horizontally; the Anglo-Saxons used them perpendicularly. At Pevensey there are courses of tile laid flat, at fixed intervals; at Earl's Barton there are perpent stones placed upright, also at fixed intervals. The object of both was the same, namely, to supply the want of good building materials by such materials as would hold them best together, and the English masons, placing these large blocks of Shelly oolite or Barnack Rag (for Earl's Barton is supplied with this Shelly oolite from that distance), had merely to fill in the rubble between them, much in the same manner as brick-work is used in timber-framed houses.

The talus table of Colchester castle is geologically of this formation, and, owing to the want of native materials, the architect used the Roman bricks he found in such abundance on the spot, both for coigns and bonds, in the same way as they were used in the castle church at Dover, and in nearly all the town churches of Colchester, and in several of the neighbourhood.

This being, as I conceive, the origin of long and short work, and its primary intention, I come next to consider two varieties that are observable, which shews that, taken by itself, it furnishes no criterion of early date.

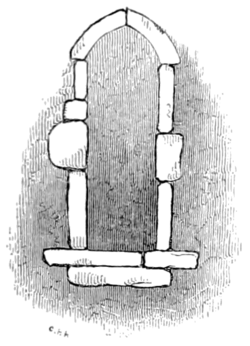

Long and short work is, first, that used for coigning; secondly, that used for upright bonding, and appearing like strips on the face of the wall.

Of the former kind there are examples in the towers at Barnack, Earl's Barton, Brigstock, and Green's Norton, and in the nave and chancel at Wittering. Of the latter kind, they may be seen at Barnack, Earl's Barton, and Stowe Nine churches, all in Northamptonshire; also at Sompting, in Sussex, Headbourn Worthy, in Hampshire, and Stanton Lacy, in Shropshire. At each of these four last-mentioned places, the long and short differs from the previous examples at Barnack, Brigstock, Earl's Barton, and Wittering. The difference may be thus described. In the Northamptonshire churches the long and short work is an important member of the angle of the towers, whilst the short stone considerably projects beyond the Hue of the long one: in the other examples both long and short stones are in the same line.

Of the second kind of long and short, namely, that used for perpendicular bonds, apparently only ornamental strips, but in reality very essential for the stability of the building, we have numerous examples besides those at Sompting, Headbourn Worthy, and Stanton Lacy. It is to some of these examples that attention shall now be directed. In the first place, by stating my conviction that the buildings where they occur are not, in reality, churches of so early a period as the preceding ones, although presenting certain marks of resemblance common to each other; and in the next, their resemblance to work of a later, in fact the Early English period, may be readily shewn.

In illustration of this I have selected examples taken from the churches of Headbourn Worthy and Stanton Lacy, which shall be contrasted with the masonry of these Northamptonshire churches, as well as with the upper portion of Oxford castle. It will be at once seen that these, although in some measure analogous to parts of Barnack and Earl's Barton, do yet materially differ from them in appearance, whilst they are also the creations of a later time.

For instance, though in Headbourn Worthy we find the perpendicular long and short bonds as at Earl's Barton, they are in conjunction with work belonging to the time of Henry III., or Edward I., that is, long and short work in union with equilateral arches; or as in the uppermost stage of the castle at Oxford, long and short work united with late Norman, or as at Stanton Lacy with earlier Norman.

It might naturally have been supposed that a reference to the Domesday Survey would have tended to settle a question of so much obscurity as the age of several of these rude and unquestionably early churches. But little that is conclusive is supplied from this source. The precept issued for the direction of the surveyors laid no injunction upon them to make a return of churches, and therefore their notice is extremely irregular, and for this reason no direct conclusion can be drawn, nor can the question be settled by reference to this document. It mentions about 1700 churches, but whilst 222 are returned from Lincolnshire, 243 from Norfolk, 364 from Suffolk, 7 from the city of York, 84 from the county, only about 20 are returned from Shropshire, one from Cambridgeshire, and none from Lancashire, Cornwall, or Middlesex. Yet it cannot be doubted that all the counties which are passed over without any mention of their ecclesiastical structures, possessed them like those enumerated. This will at once raise the number of Anglo-Saxon churches existing at the time of the Conquest, not to the extent of 45,011, mentioned by Sprott in his Chronicle, which seems incredible, but to a very considerable number, since certainly the other counties would have a proportionable amount. Is it probable that these structures were all built in the short reigns of the Confessor, Canute, and Ethelred, a period extending only over eighty-eight years? If this period should be found too short for the completion of all these buildings, then we must suppose several to belong to what may be termed the pure age of Anglo-Saxon architecture, and then it will be a consideration whether or not several buildings now held to be Norman be not in fact of an earlier date. Again, contrast the large number of edifices throughout the country which are commonly called Norman, let the style range to the accession of John (1199), with the number mentioned in the Survey, and enquire whether all these reputedly Norman buildings were likely to have been erected in the course of a hundred and thirty-three years? And may it not be probable that several of them belong to an earlier age than we have latterly been accustomed to assign them to? Nor are these all the difficulties of the question, for of the churches mentioned in Domesday, few of those reputed by as at present to be Anglo-Saxon are noticed, although churches generally through those particular counties where they exist, are comprehended in the Survey. For instance, the Northamptonshire churches of Barnack, Earl's Barton, Wittering, Brigstock, Stowe Nine churches, and Green's Norton, which all contain long and short work, are passed over. Nor yet have I been able to trace in the Survey the names of any other Anglo-Saxon churches, presumed to he so from their having long and short work, than those at Bretford in Wiltshire, Stow in Lincolnshire, Rapendune (Repton) in Derbyshire, and Stanton belonging to Roger de Lacy in Shropshire. On the other hand, no notice occurs of the church of Dorchester in Oxfordshire, although the seat of a bishopric had been removed from it but a short time before the Survey was taken. These facts, it will be observed, apply in different ways to the question before us, and it is for this reason they are adduced for examination.

Two sources of information bearing upon the history of ecclesiastical architecture seem hitherto to have met with little, if indeed any, attention. The abbatial chartularies of Great Britain probably contain a vast amount of matter bearing on this subject that deserves both carefully sifting, and comparing with the buildings to which it relates. This manuscript knowledge might very profitably be brought to bear on churches that are known to have been connected with those great establishments. To the importance of viewing ecclesiastic architecture by the aid of manorial history, as exhibited in the Inquisitiones post mortem, a more decided testimony may be borne. These illustrations may be very briefly, but conclusively, explained by the following examples, where such a method has been pursued. Passing over the noble specimens of regal architecture of a military description at Harlêch, Conway, Beaumaris, and Caernarvon, where the identity of styles, age, molds, and architecture, must be undisputed, we cannot help being struck with the extraordinary resemblance in certain points of detail existing betwixt the churches of Crick in Northamptonshire, and those of Bilton and Astley in Warwickshire, all built or re-edified by Sir Thomas Astley. The same method of comparison will also be found deserving attention when applied to the churches built or enlarged by Sir Ralph Crumbwell, the lord treasurer to Henry VI., at Colly Weston in Northamptonshire, Lambley in Nottinghamshire, and Tattershall in the county of Lincoln: and equally so the works of Bishop Burnell at Acton Burnell in Shropshire, and the chancel of the great collegiate church of Wolverhampton in Staffordshire, one of the twenty-eight manors belonging to this talented and wise prelate. The buildings in Sussex marked by the Pelham badge and buckle are well known. The students of William of Wykham's works will probably find no difficulty in detecting at St. George's chapel, Windsor, at Adderbury and Hanwell in Oxfordshire, and probably at Wolverhampton, the same kind of analogy. This may, when pursued out fully, also tend to explain further the family likeness that exists between village churches throughout particular parts of a county. It is well known that the Cistercian and Cluniac orders had their own peculiar ritual and monastic arrangements, and is it therefore too unreasonable a supposition, that the friends of those and other orders likewise should have endeavoured to copy on a smaller scale the ornaments, the decorations, and the mouldings they admiringly observed at the great church of the district? At the present day the handling of a chisel indicates to his fellow labourers the workman who was employed: the style of a building often shews by unmistakeable marks in its proportion, its design, or general character, who is the architect; and it is not hoping too much when I express the conviction that we may still obtain, by means of the present practical knowledge so generally diffused on these subjects, if united to a research of the foregoing nature, a clearer insight into, a better classification, and a positive assignment of certain structures to the piety of tenants in capite whose mouldering effigies still lie within the walls themselves, or else to other individuals whose memory may only be preserved by the national archives.

These examples will not unappropriately serve to shew how desirable it is to refrain from drawing crude and hasty generalisations, from attempting to affix precise dates to structures simply because there are found co-existing in them some features in common with similar ones elsewhere. For this reason then, caution should be observed in coming to conclusions from anomalous or isolated portions of a building, seeing that as yet we have much enquiry to make from careful measurement, as well as from records, knowing that churches were progressive in their erection, built by degrees, as the money could be obtained for the purpose, or as the masons could proceed with their undertaking, frequently commenced by one person and finished by his successor, or built by one, and improved and decorated by another. An instance in proof of this occurs in the church of Stratford in Suffolk; the lower part of the north aisle shewing in the flint-work the name of the builder and the date of 1430, whilst the porch where the inscription terminates is marked 1432. This will at once explain why incongruities so frequently exist, why we see such perpetual modifications and adaptations, and it will supply the reasons for those transitional appearances that exist at Romsey, at St. Alban's, and at many other of our most important edifices. Nor is it undeserving consideration, when chronological difficulties arise, that many of our parish churches were built by country workmen, by men who had little creative genius, and few opportunities of examining the purest ecclesiastical models, and who therefore were constrained to copy the best things near them, (which I think will at once help to account for local styles,) and whilst they were necessarily to a certain extent imitators, they would often, through negligence or through a want of fully appreciating the merits of the original, disfigure their own works by introducing into them some of its defects, probably reducing the depth of the mouldings, or disregarding the relative proportions on which much of its beauty might depend, or depriving it of those decorations which enchanted the eye, and caused it to dwell with admiration on the harmony that prevailed throughout the whole structure.

There is also another reason why we should be cautious in drawing direct and positive conclusions respecting the age of village churches, namely, that the styles were always in advance in cathedral or collegiate, whilst they were retrograde in parochial buildings. It was with architectural taste as with modern fashions, the rural population were the latest in catching the new mode.

It has, indeed, often excited astonishment, that so many beautiful fabrics should have been erected in the middle ages, when the difficulty of finding resources to build a church at the present day is so well known that the fact only needs stating. But the surprise will be diminished upon considering the altered circumstances of each period. When monastic buildings and parish churches were erected, the ecclesiastics were both influenced by different feelings than what guide them at present, and their condition also was dissimilar. At that earlier time, it is true, they were personally more indigent, especially the parish priests, but they had fewer wants, necessarily fewer from the vow under which many of them lived; they were also more zealous and skilful in carrying on the architectural works that surrounded them; they lived moreover amongst those who were animated by kindred feelings, amongst brethren, equally enthusiastic and self-denying, who sympathized and helped in the labour; thus, whilst it constituted a part of their duty, as it were, it became one of their recreations to decorate the religious house where they worshipped; and this again caused them to infuse the same ardour and the same taste at once into their superiors and their dependants.

The materials that were wanting for the purpose were usually at hand, and cost them little; the stone and the marble and the wood were easily wrought by their own tenants, whose unremitted toil they could always command; or when wages were paid they were extremely low, an opinion which is not to be negatived by urging that human wants must always keep pace with human demands and expectations, and that the difference in this respect between different periods is merely in terms of money. For after all the fact is not true; the wants of these men were the wants of nature, less artificial than those of the same class at present: their fare was coarser and simpler, beans supplied the place of wheaten food, their beverage was less stimulating and expensive, and their general habits of life were disproportionably cheaper than those of a modern artizan; added to which, these poor men believed themselves, whilst occupied in such works, to be serving the cause of God and religion, and therefore they submitted to privations and toil with patience and even joy.

Et patiens operum, exiguoque assueta juventus

Sacra deum, sanctique patres.

The persevering spirit of the priesthood was another reason. They were satisfied to begin a great work, and content to leave the merit and the fame of accomplishing it to their successors. This unselfish and unambitious spirit will at once account for its durability. Theirs was an uniform aim directed to the same object by several in succession, and all of them being imbued with the like feelings, and concentrating their means upon a common purpose, they became enabled to accomplish the great works which now call forth our admiration.

In military buildings we behold nothing at all parallel, no successive additions, no intermingling of styles, no needless decorations or profuseness of ornament, but evidences of cotemporary workmanship carried throughout the whole fortress, every part presenting the appearance of having been run up simultaneously, as if it were designed to meet a sudden emergency, which in point of fact was usually the origin of its existence. And here again the exigency was provided for by a state of things unlike any existing at present: for the barons of these noble castles had on their estates numbers of slaves, personal and prædial, whose services they could enforce; such were the subinfeudatories who held their cottages or their petty fiefs by these and similar tenures.

Again, when necessities of a more urgent nature arose, the ecclesiastics made the same appeals to the consciences or to the generosity of men that would still be adopted. The sale of articles to increase the building funds of a church was not unattempted in the fourteenth century, and by resorting to this method John de Wisbeach, a simple monk of Ely, was enabled to procure money enough to build the chapel of the Virgin Mary attached to that cathedral. For twenty-eight years and thirteen months, as the chronicle states, he was not ashamed to take whatever he could procure for the continuance of the work, not only by asking, but by begging through the country, and thus passing his life in various labours in furtherance of his pious design: by begging, and offering from a large pack at his back, such wares as he was licensed by his order to expose for sale, he completed the beautiful fabric, and transmitted his office unburdened of debt to his successor.

Again, the foundation of chantry chapels produced much of the irregularity that swells the size of churches, the gift of mortuaries, the bequest of sums of money, in some cases so profusely given, that among the wills preserved at Lynn, I have found as many as twenty churches thus enriched by the liberality of the same individual, not to mention more particularly the sale of pardons and indulgences, and the offerings left by pilgrims and devotees at the shrines of those who had a widely spread reputation for sanctity. These and similar causes were in active operation for four or five centuries, and they were in themselves productive of vast political and moral effects. It would be unfair to conceal the results of such a system; its defects were apparent in the popular insurrections that from time to time broke out and marked a progressive extension of liberty, in the gradual emancipation of the human mind, and in the naturally inherent right of following up private conviction by private judgment; it is needless to do more than barely allude to what followed. Yet in concluding the explanation I have offered it would be incomplete if I did not add that the spirit of the age was both warlike and devotional at the same time, and whilst a love of military glory inflamed the mind and aroused the fiercest passions, it was the influence of the religious orders that served to soften and lull them again to rest.

A conquering aristocracy took possession of all things, feudalism was the only form society would accept. Both Church and State were alike under its influence; the clergy alone sought to claim, on behalf of the community, a little reason and humanity. He who held no place in the feudal hierarchy, or who had not won his territory by the Sword, had no other asylum open to him than the sanctuary of the church, nor any other protector than its priests. It was a feeble protection, but the best that an enslaved people could obtain, and to a certain extent it became powerful, inasmuch as here some food was offered to the moral nature of man, and such abilities as he possessed had also the usual chance that profession offers for temporal advancement[1].

The sight of those sacred buildings which still rear their hoary pinnacles in silent praise to heaven, inspired our countrymen of old, as they should us, with a veneration for holy places. And we discharge no superstitious debt of gratitude by separating the exalted deeds of our forefathers from the lawless confusion that was mixed up with many of their actions, and giving them praise for executing the buildings we must all admire, and but vainly hope to excel.

It was no selfish or sordid spirit that was then so actively at work, no mercenary desire to aggrandise themselves by nicely balanced calculations, no speculative visions of worldly profit, from sharing in which others were excluded, but the motive power impelling them onwards through their earthly journey, was untainted by avaricious love of gain, or private gratification. The rising church absorbed every consideration; within its walls was entombed the love of native home, and family attachment and personal ambition; and thus the strongest affections, being withheld in their natural current, they were poured forth with all the increased energy of impassioned devotion upon the service of God.

- ↑ Guizot.