Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/On the History and Remains of the Franciscan Friery, Reading

ON THE HISTORY AND REMAINS OF THE FRANCISCAN FRIERY, READING.

At the north-west extremity of the town of Reading, stands what was formerly the house of the Friers Minors. It was a religious foundation of the order of St. Francis, which was introduced into England in 1224, the eighth year of Henry III.[1], and was founded in Reading in 1233.

By a deed dated that year[2] July 14, Adam de Lathbury then abbot, and the convent of Reading granted to the Friers Minors in Reading, "a certain piece of waste ground near the king's highway leading to Caversham bridge, containing thirty-three perches in length, and twenty-three in breadth, with a permission to build and dwell there so long as they should continue without acquiring any property of their own:"— for as the deed recites,—"if at any time, by any accident, or by any means, it should come to pass that the Friers Minors should have any property, or any thing of their own, they have agreed for themselves and their successors for ever, that it shall be lawful for us and our successors, by our own authority, to expel them from every part of our land, without the hindrance of any contradiction or appeal."

Under the same penalty of expulsion, the friers "were bound not to seek any other habitation on any part of the abbey lands, nor to extend the limits of what was already granted them, nor to request any thing but what was gratuitously and spontaneously allowed them, nor to receive any oblations, tithes, or mortuaries, due to the abbey. If the Friers should be expelled by the monks of Reading abbey, for any other causes than those above mentioned, it was agreed that they should be reinstated by the king's authority, and enjoy in their own right what had been granted them by the abbey. If the Friers should voluntarily relinquish their habitation, the buildings and scite of the edifice should belong to the abbey."

By a subsequent deed another piece of ground was granted them, immediately contiguous to the area already occupied by them. The conditions are the same as in the former grant, except the addition of a clause restraining them from interring in their cemetery, church, or any other place, the bodies of the parishioners of any of the churches belonging to the abbey in the town of Reading, or elsewhere, without special license. This deed is dated the 7th before the kalends of June, in the year 1285.

In 1288[3], Robert Fulco left by will to the Friers Minors in Reading, certain void pieces of ground in New-street, now Friers-street, adjoining to their former possessions. Edward I. in his 33rd year, 1306, issued a precept to John de London, clerk, constable of his castle of Windsor, to this effect;—"Whereas our beloved and faithful subject Robert de Lacey, earl of Lincoln, hath given to our beloved in Christ, the friers minors residing at Reading, fifty-six oaks of the most proper for building timber, in his wood of Asherigge, which is within the limits of our forest of Windsor; we connnand you that you permit the said friers to cut down the said oaks, and carry them wherever they please, and consult their own convenience in the same. Witness, the king at Odyham, the 11th day of January."—The buildings for which this timber was required, were not completed before 1311, as Alan de Baunebury who died at Reading in that year, bequeathed by will, "operi fratrum minorum," to the work or building of the friers minors, five shillings. The house is said to have been dedicated to St. James; but the author of the Antiquities of the Franciscans, p. 26, part ii., says he could not learn "who was the founder here, what was the title of the house, or that it had any endowment of lands," he therefore presumed that the friers here subsisted wholly upon alms.

There are few notices of the history of this religious house to be met with, as none of the registers or leiger books belonging to it are known to exist. In Leland's Collectanea, vol. ii. p. 57, is a list of the following books which formed the library: Beda de Naturis Bestiarum; Alexander Necham super Marcianum Capellam; Alexandri Necham Mythologicon; Johannis Waleys Commentarii super Mythologicon Fulgentii. Small as this catalogue is, it was probably superior in number of books to many of the libraries belonging to this order in other places; for Leland says, "in the libraries of the Franciscans nothing was observable but dust and cobwebs, for whatever others may boast, they had not one learned treatise in their possession, for I myself carefully examined every shelf in the library, though much against the will of all the brethren."

We have no account of the building, nor of the number of the friers who resided in it; from the small extent of the ground it was neither roomy nor elegant; content, agreeably to the spirit of their order, with the meanest accommodation for themselves, their principal care seems to have been to erect a house of prayer suitable to the religion they professed, and this, being substantially built, is the only part of their possessions which has withstood the ravages of time.

ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FRIERY.

as we are informed by Dr. London, in a letter to Thomas Lord Cromwell, dated Sept. 17, at Reading, in the 30th year of Henry VIII., that "as soon as he had taken the friers surrender, the multitude of the poverty of the town resorted thither, and all things that might be had they stole away, insomuch that they had conveyed the very clappers of the bells." All that now remain of the chancel is the arch, with its mouldings and jamb-shafts, which is partly bricked up in the wall of an adjoining house. There are no remains of a porch, but it is not probable that so large a church could have been destitute of this essential feature. The south doorway is of two orders, deeply recessed, and consists of a succession of deep hollows, with two members of what has been called the "pear-shaped molding;" there are no jamb-shafts, but the moldings continue down the jambs, and die away on the plinth.

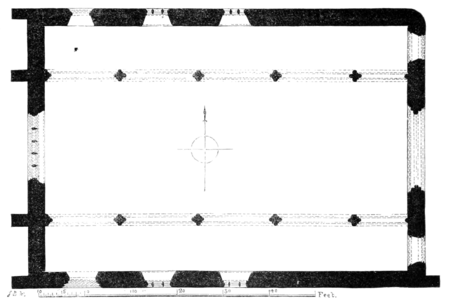

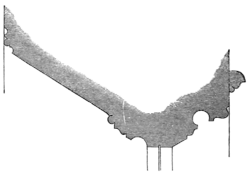

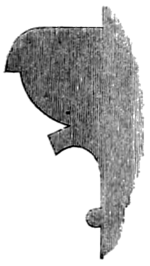

The walls are built of flint, with stone quoins, and plastered inside. Externally the flint work is laid in regular courses, and the flints split and squared. The skill and management of the old builders, and the ease with which they made the most rugged materials bend to their purpose, was never better displayed than in the construction of these walls; the thin, narrow joints, sharp surface, and beautiful appearance of the flint work, far surpasses the best attempts of modern days, and proves, whatever else the Church might have been, that it was at least the school of sound architects and good workmen. The aisles are separated from the nave by a stone arcade of five compartments, the arch nearest the chancel of each arcade being narrower and more acutely pointed than the others. The moldings of both pillars and arches are very well worked and in tolerable preservation, and belong, in common with nearly every other part of the church, to the style of architecture prevailing in the early part of the fourteenth century, now better known as the "Decorated."

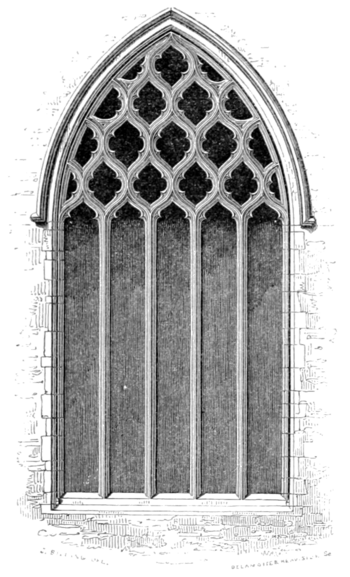

The west window is by far the finest part of the whole edifice, and even now, worn and dilapidated as it is, presents a beautiful appearance. The tracery is of a flowing character, simple but elegant, and when the west front was in its original state, with the roof complete, and the tower in the back ground completing the picture, the whole must have formed as perfect a composition as any of its kind.

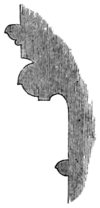

The aisle windows are of three lights, with segmental heads—the moldings are remarkably plain — but in this style we frequently find very beautiful and sometimes intricate combinations of tracery, with but meagre and shallow moldings—the heads are divided similarly to the west window, feathered and cusped. The label-mold to these windows, to the west window and arcades, is precisely the same in contour, differing only in size.

The aisles terminated with the nave, and were pierced with one east window in each; of what kind we can scarcely tell, one end being so completely covered with ivy, that it defies penetration, and the other bricked up, shews nothing but the mere outline of the window, which differs from the aisles inasmuch as it is longer and acutely pointed. There do not appear to have been any west windows to the aisles. No traces of the floor are visible, and, on digging, no remains of pavement or tiles could be discovered; the floor probably was taken up when the church was converted into a bridewell, the nave being divided off into airing yards.

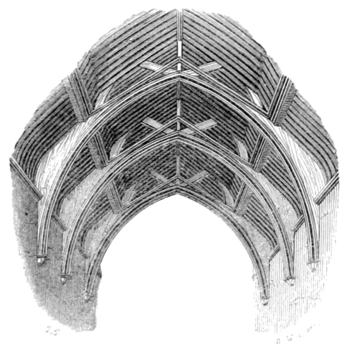

The molding upon the wall-plate, and two or three purlin braces and rafters over the aisles, are all that now remain on this site of the roof. But the roof of the nave is said to have been removed in 1786, and used instead of a new one to cover the nave of St. Mary's church; the character and appearance of the roof at present on that church, and the measurements of it, agree with this tradition, though we have not been able to obtain positive proof that it was so used.

It is to be lamented that this fine relic of ancient art is devoted to no better purpose than that of a prison. The present scanty church accommodation would be an ample reason for restoring it to a somewhat more decent state, and as the walls and arches are undisturbed, a small expenditure would render it at once fit for worship, and an ornament to the town. As before remarked, the style is "Decorated." The building was commenced in the reign of the first Edward, during whose reign, and that of the two succeeding monarchs of his name, Gothic Architecture having worked itself free from the trammels of the Norman, and the somewhat stiff though still elegant characteristics of the Early English, attained a degree of beauty and splendour unrivalled either before or since.

After existing for rather more than two hundred years, the Friery, in common with the possessions of the monks of this place, fell in the general wreck of this kind of property under Henry VIII., to whom, according to the deed of surrender, bearing the date of September 13th, 1539, the friers gave up the house with all its advantages, and finally relinquished their order.