Archaeological Journal/Volume 7/Proceedings at the Meetings of the Archaeological Institute (Part 1)

Proceedings at the Meetings of the Archaeological Institute.

January 4, 1850.

Frederic Ouvry, Esq., F.S.A., in the Chair.

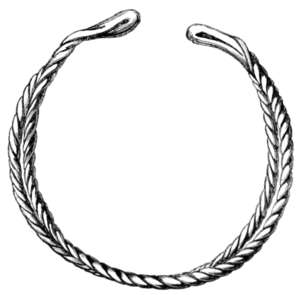

An account of the discovery, in the early part of the last year, of a remarkable collection of gold ornaments, was read; and these precious relics of antiquity, by the kind permission of Lord Digby, on whose estates in Dorsetshire they had been found, were submitted to the meeting. The discovery was made in January, 1849, at Whitfield Farm, in the parish of Beerhackett, five miles south of Sherborne. They consist of armillæ of various types; some of them of the class of tore ornaments, and others plain; they were brought under the notice of the Institute through the obliging mediation of Mr. William Ffooks, his Lordship's agent, in consequence of early notice of this curious discovery communicated to the Society by the Rev. C. Bingham. The accompanying representations exhibit the most interesting of the armillæ, and the fragments of a singular object of unknown use. The first (Fig. A) is formed of a round solid bar, without any ornament, slightly increasing in thickness towards the extremities where the ring is disunited, the ends being simply cut off and blunt. Its weight is 2 oz. 2 dwts. 21 gr. This armlet supplies a fresh example of the curious class of penannular gold ornaments, of frequent occurrence in Ireland, but more rare in this country. A specimen of the penannular gold ring, of smaller dimensions, found likewise in Dorsetshire, and now in Mr. Charles Hall's cabinet, has been given in the last volume of the Journal.[1] We are not aware that any plain gold armilla of the precise type now supplied had hitherto been found in England, their form being usually with the extremities considerably dilated, the inner side flat, or else the bar tapering considerably towards the ends.[2] The ring now found appears to present the first step from the penannular ornament formed of a simple hoop of equal thickness throughout (such as have been found in Ireland, of most massive dimensions[3]), towards the remarkable ornaments with the ends widely dilated, and forming cups, of which a specimen, found in Yorkshire, was communicated to the Institute by Capt. Harcourt.[4] It deserves notice that the weight of the penannular armlet here represented, 629 gr., is divisible by six (within a fraction—a single grain), in accordance with the rule asserted by Irish antiquaries in regard to the "ring-money" of the sister kingdom.

Fig. B.—An armlet formed of an annular piece of plain wire, fashioned so that the disunited extremities form loops, through which cither a lace or a metal hook might be passed, if any such means of attachment were desired. Weight, 11 dwt. 5 gr.—A second armlet, formed with a double wire, and looped extremities. Weight, 11 dwt. 12 gr. (276 gr. divisible by 6). This closely resembles the last, and no representation of it is given.

Fig. C. Weight, 6 dwt. 3 gr. Same size as the originals.

In the possession of the Right Hon. Lord Digby

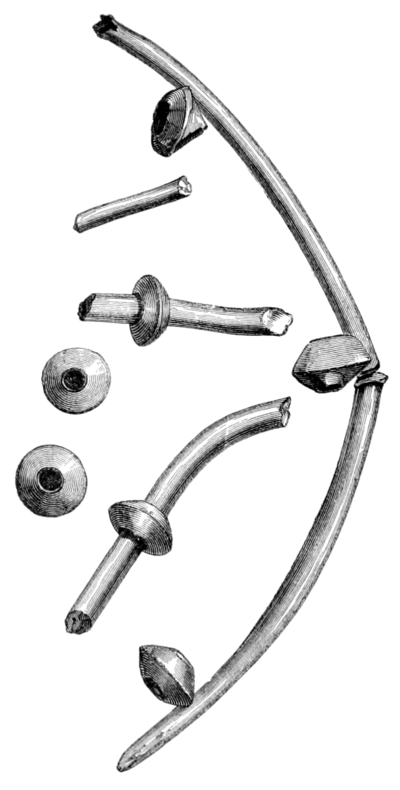

Fig. D. Fragments of tube, with beads attached, separate beads,

and portions of a solid rod of gold.

Weight, 19 dwt 7 gr. Same size as the originals.

In the possession of the Right Hon. Lord Digby.

Fig, D.—Fragments of a remarkable ornament of gold, the use of which, in its present imperfect state, it is difficult to conceive. They consist of pieces of a tube of gold, now slightly curved, and having, at intervals, hollow beads of gold attached to one side (see woodcuts). The weight of the tubes and beads, with four similar beads, not attached to the tubes, is 6 dwt. 13 gr. Also some solid portions of wire, ornamented at intervals, as if beads of similar form to those already mentioned (double truncated cones) were strung upon them. Weight of these fragments, 12 dwt. 18 gr.[6] A number of gold beads, precisely similar in form and average size, strung upon a bar of metal, were found in a cairn on Chesterhope Common, in the manor of Ridsdale, in 1814. They were presented to the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle, in the following year, by the late Duke of Northumberland.[7] His Grace stated that he had seen some similar beads of gold, placed loosely on a bar, forming the guard at the back of the handle of a sword, stated to be of the Saxon period, which had been exhibited to the Society of Antiquaries of London, some years previously. This description appears to indicate an object in some degree analogous to that now represented. Metal beads, of precisely similar form, found in Prussian Saxony, are figured by Kruse, in his "German Antiquities."[8]

The curious ornaments exhibited by Lord Digby, were found about eighteen inches beneath the surface, in digging drains in pasture land. Nothing else had been discovered near the spot, within a mile of which, in the parish of Lillington, several skeletons were found, laid side by side, one of them of extraordinary dimensions, about ten years since. Bones are often ploughed up there, and there is a tradition of battles fought near the place, of which the actual names of fields,—Redlands, Manslayers, &c.,—are in some degree confirmatory.

Mr. Charles Long communicated a Notice of the investigation of a British tumulus in Berkshire, directed by Mr. Henry Long and himself some years since, and he produced a portion of a diminutive vase, found with the interment, and of the class termed, by Sir Richard C. Hoare, "incense cups." From the fragments, aided by a representation drawn at the time, a careful restoration of the entire form has been obtained, and the accompanying illustration exhibits accurately the fashion of this curious little vessel, when complete. The barrow was situated near Stanmore Farm, at Beedon, south of the Ilsley Downs, and about two miles south of East Ilsley. On April 13, 1815, a considerable excavation was made on the south side, from which the farmer had previously taken a quantity of earth to fill up a pit, and at the depth of about ten feet a small interment was discovered. Amongst the burned bones, the fragments of the small urn were found. This deposit lay southward of the centre of the tumulus. The barrow was of the kind termed by Sir Richard Hoare "bell barrows;" throughout the soil of which it was composed there appeared veins of charred wood; the ditch which had surrounded the tumulus was much effaced by ploughing over it. The common people gave the name of Borough, or Burrow, Hill to it, and they had a vague tradition of a man called Burrow who was there interred in a coffin of precious metal. Operations having been resumed, in order to examine the centre of the hill, an excavation was made from the north side, to meet that previously cut on the south. The work was much impeded by the abundance of flints found in the soil, as also by a violent thunder-storm, which the country people regarded as in some manner caused by the sacrilegious undertaking to disturb the dead. One of the labourers employed left the work in consequence, and much alarm prevailed. After passing the flints, the cutting entered upon the clay, which again was characterised by the appearance of charred wood. Two fragments only of bone were found, near the upper part of the hill. After making a considerable excavation, a regular horizontal layer of charred wood appeared, placed on a stratum of red clay, probably the natural soil on which the tumulus had been raised, for no appearance of disturbance could be traced. The workmen found seven perpendicular holes, formed almost in a circle, around the centre of the barrow; they were about a foot in depth, and two inches in diameter, and were partly filled with charred wood. Further excavations were made, but no other interment was brought to light. It had been reported that an attempt was made twenty years previously, by night, to open the hill on the cast side, in search of treasure, but it was frustrated by the occurrence of a thunder-storm.

An earthen pitcher of ordinary glazed ware was subsequently dug up on the west side, apparently indicating some previous disturbance, but the even state of the layer of charcoal, above-mentioned, clearly showed that the centre of the hillock had remained hitherto untouched. The observations of Sir Richard Hoare have shown that the interment was not invariably central; and he remarks that the examinations of the larger tumuli generally proved unsuccessful, He alludes to the feeling of superstitious dread with which the peasantry regard such rifling of the tomb; a feeling to which very probably it may be due, that tumuli have so generally remained undisturbed, notwithstanding the prevalent tradition of concealed treasure. He mentions the dismay caused by a thunder-storm on one occasion, which the rustics of Wiltshire seem to have concluded, like those of Berks, to be a judicial visitation. It was with considerable difficulty that Mr. Long could prevail upon the tenant-farmer to give consent; his wife, moreover, had dreamed of treasure concealed on the east side, "near a white spot."[9] The Urn discovered at the Worcestershire Beacon, near Great Malvern.

Scale, half original size.

Now in the possession of Edward Lees, Esq.

The excavation was filled up, an earthen vessel, containing some coins and a memorial of the search thus carried out, having been deposited.

The little vase (of which a representation, half orig. size, is here given), is of ashy grey ware, the scorings very strongly marked, and defined with considerable care by a sharp point. A cup, of similar, but more rude fashion, was found by Sir Richard, with an interment of burnt bones, in a tumulus on Gorton Downs, Wilts.[10] Another specimen, of like form, with perforations at the sides, and remarkable as being a double cup, having a division in the middle, so that the cavity on either side is equal, was found at Winterbourn Stoke;[11] and a few other examples may be noticed, found in Wiltshire, of which one, with perforated sides, is covered by rows of bosses like nail-heads.[12] These little cups occasionally have only the lateralholes, as if for suspension; sometimes the bottom is pierced like a cullender, and sometimes they are fabricated with open work, like a rude basket, of which the most elaborate example is one found at Bulford, given in this Journal (Vol. vi., p. 319). They appear to have been destined for various uses besides that of thuribula, and deserve to be classified by aid of more detailed investigation.

Mr. Jabez Allies reported an interesting discovery illustrative of the same subject, and supplying an example of these diminutive British fictilia, hitherto almost exclusively noticed in Wiltshire tumuli. He communicated also a detailed account, with drawings supplied by Mr. Edwin Lees, of Worcester, in whose possession the urn is now preserved. In November, 1849, Mr. Lees visited the Worcestershire Beacon, on the range of heights immediately above Great Malvern, and met with some of the party engaged upon the new Trigonometrical Survey, who showed him part of a human cranium, found three days previously in excavating on the summit of the beacon to find the mark left as a datum during the former Survey. On uncovering the rock, about nine inches below the surface, just on the outer edge towards the south of the pile of loose stones, the small urn (here represented) was found in a cavity of the rock, with some bones and ashes. The urn was placed in an inverted position, covering part of the ashes, and the half-burned bones lay near and around it. Its height is 212 inches; breadth, at top, 3 inches. The bottom of this little vessel is nearly three-quarters of an inch in thickness. The impressed markings are very deficient in regularity. Another deposit of bones, but without an urn, was also found on the north side of the heap of stones, marking the summit; and this heap, although renewed in recent times as a kind of beacon, very probably occupies the site of an ancient cairn.

The discovery was made by Private Harkiss, of the Royal Ordnance Corps, who gave the fragments of the urn to Mr. Lees. On further examination of the spot, some bones were collected; and, being submitted to anatomical examination, they were pronounced to be the remains of an adult human subject, which had undergone cremation. The urn is of simple form, somewhat different in character to any found in Wilts; it bears a zigzag corded line both externally and within the lip, impressed upon the surface, as shown in the representations. (See Woodcuts, half orig. size.)

No discovery of any British urns or interments upon the Malvern Hills, had, as Mr. Allies observed, been previously made. The conspicuous position of the site where this deposit was found, being the highest point of the range in the part adjoining Great Malvern, seems to indicate that it was the resting-place of some chieftain or person noted at an early period of our history. The jewelled ornament of gold found, about 1650, in the parish of Colwall, and the more recent occurrence of a vase containing Roman coins, as related by Mr. Allies in this Journal,[13] are the chief discoveries on record as made upon the Malvern range.

The Hon. William Owen Stanley communicated notices of recent discoveries, indicative of ancient metallurgical operations in North Wales. About eighteen years since, an old working was broken into at the copper mines at Llandudno, near the Great Ormes Head, Caernarvonshire, north of Conway. A broken stag's-horn, and part of two mining implements, or picks, of bronze, were found, one about three inches in length, which was in the possession of Mr. Worthington, of Whitford, who at that period was lessee of the mines. The smaller, about one inch in length, was sent by Mr. Stanley for exhibition. About the month of October last, the miners broke into another ancient working of considerable extent. The roof and sides were encrusted with beautiful stalactites, to which the mineral had given beautiful hues of blue and green. The workmen, unfortunately, broke the whole in pieces, and destroyed the effect, which was described as very brilliant when torch-light was first introduced. On the ground were found a number of stone mauls, of various sizes, described as weighing from about 2 lb. to 40 lb., and rudely fashioned, having been all, as their appearance suggested, used for breaking, pounding, or detaching the ore from the rock. These primitive implements are similar to the water-worn stones or boulders found on the sea-beach at Penmaen Mawr, from which, very probably, those most suitable for the purpose might have been selected. Great quantities of bones of animals were also found, and some of them, as the miners conjectured, had been used for working out the softer parts of the metallic veins. This, however, on further examination, appeared improbable. These reliquiæ have been submitted to Mr. Quekett, Curator of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy at the College of Surgeons, who pronounces them to be wholly remains of animals serving for the food of man. He found amongst them bones of the ox, of a species of deer, larger than the fallow deer (possibly the red deer), of goats, and of a small breed of swine. It had been imagined also, that the bones had been taken into the cavern by wolves or foxes, but Mr. Quekett distinctly refuted this notion, no trace of gnawing being found. They were evidently the vestiges of the food of the old miners, and were in many instances coloured by the copper, which gave a bright green tinge both to the bones and the stone hammers, above described. A semi-globular object of bronze was found, about 114 in. diameter, having on the concave side the stump of a shank or spike, as it appeared, by which it might have been attached to some other object. This relic, with a stone maul, had come into the possession of Lady Erskine; they were kindly sent by her for examination. On another stone hammer appeared marks which had been conjectured to be rude characters. These simple but effective implements seem to have been employed generally by the miners of former times. Mr. Stanley stated that he had seen several nearly similar to that exhibited, and he had obtained one, still in his possession, found in ancient workings at Amlwch Parys Mine, in Anglesea. It is of hard basalt, measuring about a foot in length, and evidently chipped at the extremity in the operation of breaking other stony or mineral substances. The miners at Llandudno observed, however, that their predecessors of former times had been unable to work the hardest parts of the rock, in which the richest ore is found, for they have recently obtained many tons of ore of the best quality from these ancient workings. The original entrance to these caverns is not now to be traced. There was some appearance of the effects of fire or smoke upon the sides and roof of the cavern, when first discovered. Mr. Stanley sent, with the relics above mentioned, another rudely-shaped implement of stone, found near Holyhead. Some of these mauls were described as "two-handed;" and Mr. Worthington supposed, from the appearances, that their use had been to drive wedges, which might serve to split the rock.

Pennant, in his notices of ancient mining in North Wales, in Roman times, states that miners have on former occasions found the marks of fire in ancient mines, which he seems to attribute to the practice of heating the rock intensely by great fires, and then splitting it by sudden application of water. He was in possession of a small iron wedge, 514 inches long, found in working the deep fissures of the Dalar Goch strata, in the parish of Disert, Flintshire. Its remote age was shown by its being much incrusted with lead ore. He states that clumsy pick-axes, of uncommon bulk, have been found in the mines, as also buckets, of singular construction, and other objects of unknown use.[14]

Mr. Buckman offered some interesting remarks on the discoveries recently made at Cirencester, of which a full account is in preparation for the publication announced by himself and Mr. Newmarch, as noticed in the last volume of the Journal. He exhibited a full-sized coloured tracing of the fine female head, an impersonation of Summer, and called attention to the chaplet of ruby-coloured flowers around her head, which, when the pavement was first found, were of a bright verdigrease-green colour, as shown in a drawing submitted to the Institute at a former meeting. On subsequent examination, it was found that these parts had become incrusted, by decomposition, with a green ærugo, the colouring matter of the ruby glass being protoxide of copper. This incrustation had been removed, and the vivid original colouring brought to light, converting the chaplet of leaves into a garland of summer flowers. Mr. Buckman has kindly promised a detailed account, with some valuable particulars regarding ancient colouring materials, the result of careful analysis, to be given in a future Journal.[15]

Mr. W. A. Nicholson, of Lincoln, communicated notices of certain rudely-shaped cylinders of baked clay, found near Ingoldmells, on the coast of Lincolnshire. These singular objects, locally called "hand bricks," having been apparently formed by squeezing a portion of clay in the clenched hand, are found in no small quantity washed up after gales of wind, by which they are dislodged from the beds of black mud off that coast, in which the hand-bricks are imbedded. The sea, as it is supposed, has encroached largely on the shores in that part of the eastern coasts, and local tradition affirms that foundations of two parish churches, submerged in the German Ocean, may still be seen at very low titles, off the neighbourhood of Ingoldmells. The hand-bricks measure in length about 312 to 4 inches, the diameter is mostly greater at one extremity, apparently the base, formed by a sudden pressure on a flat surface: it is about 212 inches, and the lesser diameter about 112 or 2 inches. It is remarkable that they appear to have been formed mostly with the left hand. Fragments of rude pottery have occasionally been found with the bricks. Mr. Nicholson presented a specimen of the bricks to the Museum of the Institute, (See Woodcut.) Another was exhibited by the Rev. T. Reynardson, in the Museum formed at Lincoln during the meeting of the Institute. It was precisely similar in fashion, and was described as having been found amongst the vestiges of a submerged church, near Wainfleet, being supposed to have been used in its construction.Mr. Franks laid before the meeting another "hand-brick," found in Guernsey, and closely resembling those which have been noticed in Lincolnshire: in general appearance and dimensions they are identical. It had been given to him by Mr. Lukis; and Mr. Franks stated that, according to the opinion of that distinguished archaeologist, these cylinders had served some purpose, probably as supports for the ware when placed in the kiln, in ancient potteries in the Channel Islands. The occurrence of fragments of fictilia with the bricks found in Lincolnshire, appears to corroborate this conjecture regarding their use in the operation of firing ware.

It has been stated that vestiges of Roman occupation may be traced on the coast of Lincolnshire. In the district of East Holland, there is an ancient embankment, commencing south of Wainfleet, and following the line of the coast, towards lugoldmells, designated as the "Roman bank."

Mr. Edward A. Freeman, Author of the "History of Architecture," communicated an interesting account of the Anglo-Saxon remains existing in the church at Ivor, Bucks, discovered during recent works of restoration. Some portions of masonry, apparently of an earlier age than the Norman work of that fabric, were brought to light, with indications that the original building had been destroyed by fire. This memoir will be given in a future Journal.

The Rev. Francis Dyson laid before the Meeting a detailed plan of recent discoveries at Great Malvern, at the eastern end of the Abbey Church, accompanied by notices of the progress and results of late excavations, in the direction of which he had taken an active part. The foundations of the Lady Chapel and some adjacent buildings have been brought to light; the only indication which had been preserved of the form of that portion of the structure, is given by Thomas, in the plan taken about 1725. (Antiquitates Prioratus Majoris Malverne, &c.) The dimensions proved to be inaccurately laid down. The remains of a crypt and the springers of a groined roof were found, of an earlier period than the existing conventual church. Some indication of this crypt had previously been noticed in the appearance of a small doorway in the eastern wall of the church, and of a descent from it. Subsequent investigation has brought to light other vestiges, with the foundations of the Chapel of St. Ursula, forming a kind of transept on the south side; also portions of tile-pavement and details which, on the conclusion of this interesting examination, will be more fully described, with the plan kindly presented to the Institute by Mr. Dyson. The remains of the crypt were considered to be of the Early English period, but fragments of tracery and mouldings found in it, probably the debris of the superstructure (the Lady Chapel), were of a later style.

Antiquities and Works of Art exhibited.

By the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.—A bronze fibula, of Roman workmanship, with enamel of red and blue colour inlaid on the central boss, A fibula of similar fashion, but varied in the enamelled design, may be seen in Montfaucon, Ant. tome iii. pl. 29. A bronze fibula, of the harp shape, found with Roman remains at Stanford Bury, near Shefford, Bedfordshire, in 1834. An account of the discoveries there made, is given in the Transactions of the Cambridge Society, in a Memoir by Sir Henry Dryden, Bart., p. 20. A curious fibula, formed of one piece of brass wire, 512 inches in length, the elastic spring of the acus being contrived by four convolutions of the wire. It was found at Pirton, Bedfordshire (Ib., p. 21.) Two round white stones, or pellets of vitreous paste, convex at top, the under side flat. Four of a white colour, and one black one were discovered together, with various Roman remains, " Samian" ware, &c., at Stanford Bury, near Shefford. The late Mr. Inskip supposed that they had been used for some game. In a fresco at Pompeii, representing Medea meditating the murder of her children, they appear playing with black and white calculi on a table resembling our draught-board. They may, however, have been used for the abacus or counting-board. The representation here given is of the same size as the original. Also a tessera (?) or round counter, impressed with the letter E, and Roman numerals XII. It is of burnt clay, of a red colour, and well compacted. Numerous round counters of this description have been found in various places, and occasionally with Roman remains. On one found in Northamptonshire, and communicated by the Rev. Abner Brown, of Pytchley, the like initial E appears over the numeral III. There are several in the Museum of the Hon. Richard Neville. Their true age and intention remain to be determined.

With these antiquities were also exhibited two very interesting circular fibula), of the "saucer" form, found by the late Mr. Inskip at Shefford.[16] They have been supposed to belong to the Anglo-Saxon period, and were discovered in an ancient cemetery, in which numerous Anglo-Roman vases and remains were found, but the interments were probably of successive periods of occupation. These interesting brooches were gilt, the centre chased with a peculiar design (see Woodcuts of fibulæ), surrounded by impressed ornament. The decoration was similar in both examples. The acus had been of iron. Fibulæ of this type are rare: the finest examples known are in the possession of the Hon. Richard Neville, and were formerly in the Museum at Stowe. They were found at Ashendon, Bucks, and are of very unusual size, diam. 314 inches. They are jewelled, and the arrangement of ornament is cruciform. A bronze fibula, of the same type, found at Stone, in Bucks, is engraved in the Archæologia, Vol. xxx., p. 545. Two others, found in Gloucestershire, are given in the Journal of the Archaeological Association, Vol. ii,, p. 54, and Vol. iv., p. 53.

By Dr. Mantell.—A beautiful gold ring, set with an uncut sapphire, found on Flodden Field.—The seal of the Deanery of Paulet, co. Somerset, found near Winchester.

By the Rev. E. Venables, Local Secretary in Sussex.—Impression from the sepulchral brass of an ecclesiastic, in the mass-vestment, from the church of Emberton, Bucks. The figure measures 3012 inches long. From the upraised hands proceeds an inscribed scroll—"Ion preyth' the sey for hȳ a pat' nost' & an aue." The inscription beneath the feet is singular, commemorating the benefactions of the deceased in service-books given to certain churches—"Orate p' aīa M'ri Johīs Mordon al's andrew quond'm Rectoris isti' eccl'ie qui dedit isti eccl'ie portos missal' ordinal' p's oculi in crat' ferr' Manual' p'cessional' & eccl'ie de Olney catholicon legend aur' & portos in crat' ferr' & eccl'ie de Hullemortoñ portos in crat' ferr' & alia ornamenta. qui obijt (blank) die Mens' (blank) Au° dñi M°. CCCC°. X (blank) cuius aīe p'piciet' deus Amē." The dates have never been inserted, this sepulchral portraiture having been placed in his lifetime, probably before 1420, and in commemoration of his donations, possibly as a security for their preservation, as was frequently sought by the anathema, "quicunque alienaverit." The term crat' ferr' has not been explained, and some conjectural interpretations were suggested. Crata or crates is a grating, such as the inclosure of a tomb or chancel; the trelliced railing near an altar is termed "craticea ferrea." It may perhaps imply a kind of iron frame or lectern on which the Porthose (portiforium) missal, ordinal, and other books thus given were placed, or a grated receptacle for their safe preservation.[17] The donor possibly took his alias from Hill-Morton, a parish in Warwickshire, to which he gave a portiforium and ornaments of sacred use,—ornamenta, a term denoting the vessels or customary appliances of the altar.

By Mr. Way.—Impressions from several incised slabs existing in France, comprising the effigies at St. Denis, attributed to two abbots of that monastery (see the representations given in this Journal, p. 48), and the fine figure of the architect by whom the earlier portions of the Abbey Church of St. Ouen, at Rouen, were built,—namely, the choir and chapels surrounding it. The work commenced A.D. 1319. No record of his name has been ascertained. He holds a tablet, on which is traced a window and cornice, resembling precisely the work attributed to his design. Also, the beautiful figure of John, Chancellor of Noyon, who died 1350. This slab is preserved at the Palais des Beaux Arts, Paris, and is represented admirably in "Shaw's Dresses and Decorations."

By Mr. Magniac.—A beautiful casket of the choicest enamelled work of Limoges, of the sixteenth century. The cover is ridged, like the roof of a house; dimensions, 634 inches by 412 inches; height about 5 inches. The paintings are in grisaille, with slight flesh tints, green and blue tints are partially employed. The subjects are chiefly from Old Testament History, representing the death of Abel, Lot leaving Sodom, Moses and the Golden Calf, the Israelites gathering Manna, David and Goliath, Daniel in the Lions' den, Daniel destroying the dragon Bel, the Burning of the Magical Books, and the preservation of the Scriptures concealed in a receptacle like a tomb or vault;—"SEP. LARCHO: DV. VIES. TESTEMAN."

By Mr. Webb.—An enamelled reliquary of the work of Limoges, in the twelfth or thirteenth century. Its dimensions are 6 inches by 214 inche ; height, 734 inches, including a pierced crest. The form is that of the high-ridged shrine. It exhibits, at the ends, two figures of saints, with red nimbs, apparently a male and a female figure; at the sides are demi-figures, bearing books; it is enriched with imitative gems, uncut, and has tranverse bands of exquisite turquoise-coloured enamel.

February 1, 1850.

Octavius Morgan, Esq., M.P., in the Chair.

Mr. W. Wynne Ffoulkes communicated notices of his investigations, during the past summer, of certain ancient remains in the interesting district of the Clwydian Hills, Denbighshire, and he laid before the meeting various fragments of fictile vessels there discovered, interesting as evidence of the age and people to whom these vestiges are to be assigned. The excavations were made in an encampment crowning the summit of Moel Feulli, a conical hill south of Moel Famma, about three miles west of Ruthin. Portions of ancient ware, of various kinds, were brought to light, not many inches below the original surface of the ground, and underneath the rampart on the north-east of the camp, the side of which it was necessary to scarp away for about six inches, in order to reach these remains: there were ashes mixed in the adjacent soil. The specimens appear to be all of Anglo-Roman fabrication, and of the coarser kinds of ware; one is incrusted with small particles of hard stone, as found on the inner surface of some "Samian" vessels and mortaria. Mr. Ffoulkes stated, that there is an urn preserved in the Caernarvon Museum which is incrusted in like manner. Another specimen was decorated with scroll patterns, laid on superficially in thick slips of a lighter colour than the vase itself. Some researches were also made at Moel Gaer, part of Moel Famma, and at Moel Arthur, to the northward of it. In these two encampments fragments of Roman pottery were found, of a red colour, and other ordinary wares of the coarser description, but sufficing amply to show that these singular hill-fortresses, on the confines of Denbighshire and Flintshire, had been occupied by the Roman invaders, although, probably, coustructcd as places of security in much earlier times. Mr. Neville, on examining the portions of various ware exhibited, expressed his persuasion that they were all of Anglo-Roman fabrication, and similar in character to those which had become so familiar to him in the course of his frequent excavations at Chesterford. Mr. Ffoulkes intimated his intention of prosecuting his investigation at some future occasion.

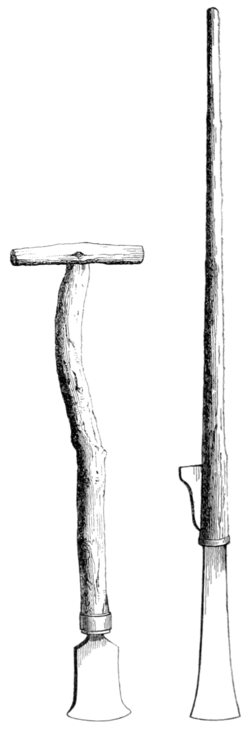

Mr. Yates read an interesting communication, which he had received since the publication of his Memoir on the use of Bronze celts, from Dr. C. J. Thomsen, of Copenhagen. He had kindly sent two drawings, copied in the annexed wood-cuts, which show the form of the "paalstav," now used in Iceland, and called there by that name.[18] They are drawn one-eighth of the real size: the blade is, consequently, about 8 centimetres (rather more than three inches) broad. The larger of the two implements is 1⋅09 metre long, including its haft. The only circumstance in which it differs from the ancient celt of Mr. Du Noyer's fourth class, is that, instead of being attached to the haft by thongs or cords, as Mr. Yates had supposed to have been the case anciently, in these implements the bottom of the shaft is bound by an iron ring; and there seems to be no reason to doubt that a metallic ring may have been used occasionally in ancient, just as in modern times. Dr. Thomsen remarks, that these palstaves are used to break the ice in winter, and to part the clods of earth, which, in Iceland, is dug and not ploughed. This presents a striking coincidence with the precepts of Roman writers on agriculture: "Nee minus dolabra quam vomere bubulcus utatur;" and "Glebæ dolabris dissipandæ." The reader will observe in the larger of these two figures a confirmation of Mr. Yates' conjecture respecting the use of the vangila. In addition to the numerous localities mentioned in his Memoir, Dr. Thomsen has heard that palstaves have been found in ancient stone quarries in Greece.

Mr. Yates exhibited also drawings of some remarkable bronze celts, preserved at Paris, in the Museums of Antiquities at the Louvre and at the Bibliotheque Nationale. They are novel types, unknown among English antiquities of this nature. Another bronze object, which he had noticed on the continent, appeared to have been intended to form the core of a mould.

Mr. Birch communicated a memoir illustrative of an interesting fragment of basalt, portion of an ancient Egyptian calendar, in the form of a circular vase, and sculptured with hieroglyphics, amongst which occur twice the cartouches containing the name and titles of Philip Arrhidæus. This fragment comprises the month Tybi, corresponding to November, with part of October. Its value consists in its being an addition to the small number of monuments of the early period of the sway of the Lagidæ in Egypt. Mr. Birch fixes its date as between B.C. 323—306. No monument of the reign of Arrhidæus exists in the British Museum. This curious relic had been recently found amongst the antiquarian collections of the late Ambrose Glover, the Surrey Antiquary, at Reigate, and it was brought before the Institute by Thomas Hart, Esq., of that town, its present possessor.[19]

Dr. Thurnham gave a report of the recent examination of tumuli in Yorkshire, some of which have been assigned to the Danish period. See this Notice at a previous part of this Journal, p. 33.

The Rev. J. L. Petit communicated a memoir on the remarkable features of Gillingham Church, accompanied by numerous beautiful illustrations, reserved for publication in a future number.

Major Davis, 52nd Regt., gave an account of churches in Brecknockshire, illustrated by many interesting drawings. It will be found at a previous page. He exhibited also several drawings of choice enamelled objects, views of architectural remains in Ireland, and other subjects.

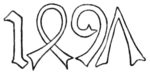

The Rev. Edmund Venables, referring to the early examples of the use of Arabic numerals, cited in the last volume of the Journal,[20] and that existing at Heathfield Church, Sussex, 1445, stated to be the earliest observed on any architectural work, expressed the wish that further investigation of this curious subject might be encouraged, and that the members of the Institute should be invited to send notices of any other dates of the fifteenth century, in other parts of the country. He sent two dates, one (only three years later than that noticed at Heathfield) from the Lych-gate at Bray, Berkshire, the other from a quarry in the window of a passage leading from the kitchen to the hall, at St. Cross, Hants. The first is the date 1448, carved on one of the wooden posts supporting the Lych-gate, on the left hand on entering the church-yard; the wood is much weathered by exposure, and the surface too rough to admit of a very precise facsimile being taken. The annexed representation, however, gives an accurate notion of the forms of the numerals. The originals measure about 112 inch in height. The Lych-gate itself is a structure of considerable interest, having two ancient chambers over it, connected with some charitable bequest.[21] It has been partly modernised, the plaster panel-work having given place to brick. An account of Bray and of this building has been given by the Rev. G. Gorham. in the "Collectanea Topographica."The date at St. Cross (see wood-cut, next page) occurs with the motto—"Dilexi sapientiam." being that of Robert Shirborne, Master of the Hospital, collated to the see of St. David's in 1505. The singular appearance of the numerals had perplexed many visitors, but the difficulty was solved by Mr. Gunner, who ascertained that the window having been re-leaded, the quarry was reversed, the coloured side being now the external one. The date proves accordingly to be 1497.[22] These numerals measure about 114 inches in height.

The Rev. W. Gunner sent also rubbings from two other dates at St. Cross, carved on stone, .and of the times of the same Master. One of these is in the porter's lodge, the other on the mantle-piece of the fire-place in an upper chamber, now called "the Nun's room," part of the old Masters' lodging, supposed to have been the work of Robert Shirborne. It is carved on a scroll, as follows—"R S Dilexi Sapiēciam anno doi 1503.[23]" The date is the same in both instances, and the unusual form of the 5 (similar to the letter h) renders it deserving of special notice. This form occurs, however, in the "chiffres vulgaires de France," given by De Vaines.[24] It is found in the date of the sepulchral brass of Robert Mayo, in the church of St. Mary, Coslany, Norwich, given in Mr. Wright's curious memoir "on the antiquity of dates expressed in Arabic Numerals," in the Journal of the Archaeological Association.[25] It is identical with the character quinas, the fifth of the numerical symbols used by Gerbert, in the system of calculation introduced about the close of the tenth century.

The curious piece of plate presented by the same Bishop Langton to Pembroke College, Cambridge (as stated by Godwin), and still there preserved, usually termed the "Anathema cup," bears' an inscription, in which both Roman and Arabic numerals are found united. It is as follows:—C. langton winton' eps aule penbrochie olim soci' dedit hāc tassēā coop'tā eidē aule 1 • 4 • 9 • 7 qui alienaberit anathema sit. lxbii. bnc̄.

The anathema has not availed for the preservation of the cover of this tassea. A representation of the cup is given in Mr. Smith's interesting "Specimens of College Plate," (Transactions of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, vol. i.)

Mr. Ouvry presented to the Institute a plaster cast of another date, 1494, in Arabic numerals, which is seen over the west door of the church of Monken Hadley, Middlesex. A representation is given in Camden's "Britannia." The church is supposed to have been erected by Edward IV., as a chantry for the performance of masses for the souls of those who fell at the battle of Barnet, in 1491. On the dexter side of the date is a rose, and on the other a wing, which have been explained as a canting device for the name Rosewing, one of the priors (?) of Walden, to which house Hadley belonged. The same device occurs over one of the arches of Enfield church, also dependent on Walden.[26]Antiquities and Works of Art exhibited.

By Mr. William W. E. Wynne, of Sion.—A round buckler of thin bronze plate, with a central boss, on the reverse of which is a handle; it is ornamented with seven concentric raised circles. It was found in a peat moss, at a depth of about 12 inches, near a very perfect cromlech, about 400 yards south-east of Harlech, and lay in an erect position, as Mr. Wynne had clearly ascertained by the marks perceptible in the peat where it was found. One part, being near the surface, had, in consequence, become decayed, but the remainder is in excellent preservation. (See woodcut.) It measures, in diameter, 22 inches. Several bronze shields have been found in Great Britain at various times. The example most analogous to that now noticed, was found near Ely, in 1846, and is preserved in the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Cambridge, in whose transactions it is represented, with notices of similar objects. Sir Samuel Meyrick designated the circular bronze buckler of this description as the tarian; the more common type presents concentric rings, beaten up by the hammer, with intervening rows of knobs, imitating nail-heads. He speaks also of such objects as the "coating" of shields, but the position of the central handle seems ill adapted if such were the intention. Mr. Wynne exhibited some bronze spear-heads, found, in 1835, near the Wrekin, as related by Mr. Hartshorne, in his "Salopia Antiqua."[27] Also an iron weapon found in the peat at the Wildmores, near Eyton, Salop, a kind of bill, with the point formed into a hook, supposed to have been used either to catch or to cut the bridle in a conflict between footmen and cavalry. Length 12 inches. Mr. Neville remarked that he had discovered one of precisely similar form, but rather smaller, in excavations at Chesterford.

By the Hon. Richard Neville.—An intaglio of very superior art to that usually displayed on gems found in sites of Roman occupation in England. The gem is a red jasper. It represents "Lætitia Autnmni"? a figure bearing ears of wheat, and game. It was discovered in the course of recent excavations at Chesterford.

By Mr. Newmarch.—Several very striking drawings of large dimensions, exhibiting more perfectly than the tracings displayed at former meetings, the beauty and variety of design so much admired in the tessellated pavements lately found at Cirencester, of which there are fac-simile representations of the size of the originals. They have been prepared with the utmost care for the forthcoming work on Corinium.

By Mr. Evelyn Philip Shirley.—A small plate, of champ-levé enamel, circa 1350, intended to decorate some piece of metal-work, possibly affixed to a belt, or inlaid in the centre (or "bussellus," the little boss) of the round dish or charger formerly much in use. It was found in January, 1850, in the ground close to the manor-house of Nether Pillerton, Co. Warwick, belonging to the Rev. Henry Mills, in whose possession this curious little relic remains. The accompanying woodcut accurately shows its form and the heraldic charge, being the coat of Hastang, a Warwickshire family of ancient note. The bearing, however, here appears with some difference of colouring. Hastang bore, Azure, a chief gules, over all a lion rampant Or. On this plate the chief is azure, and the field was evidently gules, when freshly enamelled; but a chemical change has taken place,—the cupreous base of the red colouring having been converted into a green incrustation, under which traces of gules may be discerned. This may be an accidental error of the enameller's, or perhaps a difference used by some branch of the family, although not recorded. Dugdale states, that Sir John Hastang, the last of the family, died 39 Edw. III , leaving two daughters, his heirs, who married into the families of Stafford and Salisbury. The parish of Wellesbourne Hastang, where the family held possessions, is not far from Pillerton; they gave also their name to Lemington Hastang, Warwickshire, where may be still seen in a north window a scutcheon of their arms, in brilliant ruby and azure. Mr. Shirley remarked, in regard to ancient heraldic differences in tinctures, that the Roll, t. Edw. II., edited by Sir Harris Nicolas, gives several cases exactly in point. Sir John Strange (p. 6) bore. Gules, two lions passant, argent. Sir Fulk, argent, two lions passant gules.—Sir Fulk Fitzwarin, quarterly, argent, and gules, indented, a mullet sable. Sir William, quarterly, argent and sable, indented. Many other examples might be cited. The Roll cited gives the coats of five of the Hastang family, but none of them have the chief azure.

By Mr. Edward Hoare, Local Secretary at Cork.—A representation of a remarkable bronze fibula, formerly in the Piltown Museum, formed by the late Mr. Anthony.[28] It was found, in 1842, in the Co. Roscommon, and isaccurately pourtrayed by the accompanying woodcut, half the size of the original. This type of fibula appears, as Mr. Hoare remarked, to be almost peculiar to Ireland, and the example here given is one of the largest of the kind. The diameter of the ring is 412 inches; length of the acus, 714 inches. It had evidently been much worn. The precise mode of use of these singular ornaments has been often a matter of discussion; Mr. Hoare expressed the opinion that they might have been worn in the hair, to fasten the luxuriant tresses for which the Celtic race of the Irish women are still remarkable, and have served the same purpose as the spintro commonly used by the females of Italy. The peculiar form of these ancient fibulæ, of which several specimens of extreme richness have been figured by Mr. Fairholt, in the Gloucester Volume of the Archaeological Association, may seem to present some analogy to that of the various "penannular" ornaments found in Ireland.By the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.—Several ancient signet rings, found in Cambridgeshire; the cross-bar, or frame, of an aulmoniére, of metal curiously inlaid with niello; and other relics found near Cambridge.

By the Rev. William Gunner.—Three ponderous iron hammers, and two objects described as small anvils, supposed to have been used by armourers, and found in the ancient entrenchment at Danebury Camp, near Stockbridge, Hants. Mr. Hewitt, however, stated that these relics presented no indication of having been destined for the purpose conjectured.

Numerous impressions of sepulchral brasses were exhibited, and presented to the collection of the Institute, comprising the following.

By Mr. Lowndes.—From Dunstable Church, Bedfordshire.—Lawrence Cantelowe and six sisters; circa, 1420. A figure of a lady, concealed by a pew; circa, 1480. Henry Fayrey and his wife, shrouded figures, 1516. Richard Pynfold and his wife, 1516. A shrouded figure, early sixteenth century; and a woman with her two husbands; circa, 1600.

From Luton Church.—Figure of Hugh atte Spetyle, inscription to the memory of himself, his wife, and son, a priest; circa, 1410. A lady, veiled and barbed; the figure is placed under a triple canopy; circa, 1430. Edward Sheffeld, canon of Lichfield, 15. John Acworth, Esq., and two wives, 1513. John Lylam and two M-ives, 1513. Robert Colshill and wife, 1524.

By Mr. W. W. Wynne.—From Puttenham, Surrey.—A small figure of Edward Cranford, Rector, in the mass vestment; 1431.

By Mr. Charles Long.—From Lambeth.—A figure of a man in armour; circa, 1520. Lady Catharine Howard, in an armorial mantle, 1535.—From Draycot Cerne, Wilts.—Sir Edw. Cerne and his wife; circa, 1395, hands conjoined.—From Dauntsey.—Sir John Danvers and his wife, 1514. A figure in secular costume, and his wife.

By Mr. C. Desborough Bedford.—A MS. volume, containing genealogical and heraldic evidences relating to the ancient French family of the Comte de Lentilhac Sediére.[29]

By Mr. W. Jenvey, Churchwarden of Romsey.—A small jewelled cross, appended to a chain, found in September, 1839, amongst some rubbish taken from the roof in the south transept of Romsey Abbey Church, Hants. It is of the Latin form, the terminations of the limbs quatrefoiled, the face being set with garnets (?) and the reverse ornamented with transparent blue enamel. Also, a collection of jettons, or Nuremburgh counters, found during the repairs of that structure, a half-groat of Henry VIII., minted at York, two tokens of the Corporation of Romsey, and one of Southampton.

By Miss Isabella Strange.—An elegantly-enamelled ring, probably of Oriental workmanship, the enamel being laid upon the gold in considerable relief, representing birds and flowers, as if embossed on the surface. It had been long preserved in the family of the distinguished engraver, Sir Robert Strange.

By Mr. Way.—A copy of the Book of Common Prayer, printed by R Jugge and Cawood, London, 1566, which has been viewed with interest, as bearing the arms, emblazoned in colours, and the initials, of William Howard, first Baron Howard of Effingham, created by Mary in 1553. The arms, impressed on both sides of the binding, and painted, are those of Howard, quartering Brotherton, Warren, and Bigot. The escutcheon is surrounded by a Garter, and beneath is the old family motto, "sola virtus invicta." It has been preserved in the Reigate Public Library, in a chamber over the vestry, north of the chancel. This distinguished statesman possessed by descent from the Warrens a moiety of the manor of Reigate; and he appears to have had a residence in the neighbourhood. His son, the Earl of Nottingham, "Generall of Queene Elizabethe's Navy Royall att sea agaynst the Spanyards invinsable Navy," was interred in Reigate Church, as were many of his noble house, by some of whom this Book seems to have been used, subsequently to the death of the first lord, in 1573 (whose initials it bears), a copy of the Old Version of the Psalms, printed by G. M., 1637, having been inserted at the end, and the original binding preserved.

By Mr. Ormsby Gore, M. P.—An oriental vessel of tutenag? and bronze, elegantly ornamented with bands at intervals, engraved and partly enamelled. It was found in Willow-street, Oswestry.

By Mr. Forrest.—A covered cup, on a foot like a rummer, supposed to be of wood of the ash, considered to be gifted with certain physical virtues. Various devices, some of them apparently heraldic, and quaint inscriptions, are slightly incised upon it. On the cover is an elephant, placed on a torse, like an heraldic crest, a bird upon his back; an ostrich, with a horse-shoe in its beak; a porcupine; and a gryphon. Around the rim is inscribed, "Giuo thankes to God for all his Gyfts, shew not thy selfe vnkinde: and suffer not his Benifits to slip out of thy minde: consider What he hath Done for you." On the bowl of the cup appear the lion statant, the unicorn (under which is the date 1611), a dragon placed on a torse, and having in its beak a human hand couped,—and a hart lodged, ducally gorged and chained. Around the rim of the bowl and the foot are inscriptions of a similar kind, as also on the under side of the foot. The height of the cup with its cover is 1112 inches. It had been conjectured that this cup might have served in some rural parish as a chalice; this might seem probable from the following distich inscribed upon the foot:—

"Most Worthy Drinke the Lord of lyfe Doth Giue,

Worthy receivers shall forever Line."

A wooden cup, of like form, height 14 in., bearing the elephant, gryphon, porcupine, and salamander, on the cover; on the bowl, the ostrich, unicorn, wivern, and stag statant, with date, 1620, and inscriptions differing from those found on this cup, was in the possession of Mr. W. Rogers, and was exhibited to the Society of Antiquaries, in 1843. (Described in their printed Minutes, vol. i., p. 15.)

By Mr. Farrer.—A remarkable triptych altar-piece, representing the Resurrection and final Judgment. This striking work of art bears the monogram of Albert Altdorfer, born at Altdorf, in Bavaria, 1488. In the foreground are a series of kneeling figures, exhibiting very curious peculiarities of armour and costume. They appear to be of three generations—the eldest bears arg. a lion rampant guardant, or, impaling barry of six, arg. and sa. His wife kneels near him. The son (?) bears on his breast the same lion, and, on his armorial tabard, his maternal coat; behind him is his wife, her arms are, Gu. a bend arg. between six fleurs de lys. Behind them appears their daughter, and on the opposite side, behind the first pair, is her husband. Several children are seen near them; their patron Saints, with other curious details, Paradise and eternal punishment, complete this highly interesting early example of the German school.

By Mr. Webb.—A remarkably fine enamelled painting, of the earlier part of the fifteenth century, with rich transparent colours, the enamel laid upon foil, or paillons, imitating gems, and admirably illustrative of the style of art previously to the introduction in France of an Italian character of design. The subject is the Annunciation. The Virgin appears kneeling at a fald-stool, on which is a book; in front is seen Gabriel, kneeling on one knee, and pointing with a jewelled sceptre to a figure of the Almighty, above, represented with the Papal tiara, and orb; the Holy Spirit descending from his bosom. There are several attendant angels, and an arched canopy studded with sparkling paillons, rests on an architrave supported by columns. On the architrave are figures of two aged men, with scrolls inscribed, "O mater dei memento mei." The accessories and hangings of the chamber are singularly elaborate; in front stands a vase, with a lily. The transparent enamels of the robes are of great brilliancy.

Also an enamel, painted by Leonard Limousin, in 1539: the portrait of Martin Luther; a choice specimen of the art of Limoges.—An ewer, of the peculiar fabrication termed "faïence de Henri II.," of the greatest rarity,[30] It is an admirable specimen, and in the most perfect state of preservation. This kind of manufacture is attributed to some of the Italian artists brought to France by Francis I., the precursors of the revival of decorative fictile works in that country, in the time of Bernard Palissy.—An exquisite sculpture in wood, representing the Virgin and Infant Saviour. It is the work of Hans Schaufelein, a painter and skilful engraver on wood, in the style of Albert Durer, and who, like that great artist and others, hiscontemporaries, occasionally executed small sculptures in wood or stone. He died about 1550.—An exquisite Flemish carving, in pear-wood, representing Adam and Eve in Paradise, surrounded by a frame of most elaborate and delicate workmanship, in which is introduced, above, the Lamb slain and placed on the altar, with the words, "Dlam is van aendegin gedoot." On one side is the conflict of the Demon with Man, on the other the Demon victorious. Beneath,—"Invidia autem diaboli mors introivit in orbem terrarum, imitantur autem illum qui sunt ex parte illius." Date, about 1600.

By Mr. J. H. Le Keux.—Two pairs of knives and forks, beautiful examples of highly-finished English cutlery. The silver-mounted ivory handles are curiously inlaid with silver filagree: one pair have inserted on the handles small silver coins of Charles II., James II., and Queen Anne.

March 1, 1850.

Sir John P. Boileau, Bart., V.P., in the Chair.

On opening the proceedings, the Chairman took occasion to advert to the preparations for the Exhibition of works of Ancient Art, already prosecuted with the most satisfactory effect, under the auspices of a very distinguished Committee of Management, over which H.R.H. Prince Albert had graciously consented to preside. The high interest of such a collection, and the important influence which it was calculated to produce upon the taste and design of present times, had been, as was anticipated, warmly recognised. Sir John Boileau regarded with satisfaction that the recent diffusion of an enlightened taste for Archaeological inquiries had insured the signal success of an undertaking, which, in former times, would have been attended with many difficulties, or even viewed with contempt. The cordial interest with which the proposal had been entertained, was mainly due to the zealous endeavours, during the past six years, of the Archaeological Institute and the British Archaeological Association, whose meetings and publications had given so powerful an impulse to the extension of antiquarian science. He felt assured that the members of the Institute would cordially co-operate in giving full effect to the interesting exhibition about to be opened by the Society of Arts.

A memoir was communicated by Mr. Harrod, Local Secretary at Norwich, describing the curious remains supposed to be the vestiges of a British village of considerable extent, in Norfolk. The result of his observations, which were admirably illustrated by a large map of the locality, known as the "Weybourn Pits," will be published, on the completion of Mr. Harrod's careful investigations, in the series of contributions to "Norfolk Archaeology," produced by the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society. The village of Weybourn is near the sea, at the northern extremity of a range of cliffs extending towards Yarmouth. The pits are mostly circular, from 7 to 12 feet in diameter, and 2 to 4 feet in depth. Occasionally two or three pits are connected by a trench. The floors are carefully made with smooth stones. No pottery or remains have been found. The pits are very numerous, and are doubtless the vestiges of primeval habitations. They are formed in a dry sandy spot, overlooking a fertile district. To the north are numerous small tumuli.

A notice was then read, relating to the fine collection of antiquities brought before the meeting by the Hon. Richard Neville. They consisted of bronze vases, of exquisite form, cinerary urns of glass, a bronze lamp, and some other remarkable remains, discovered some years since near Thornborough, Bucks, on the estates of the Duke of Buckingham, in a tumulus, which proved to be the depository of the richest series of Romano-British remains hitherto explored, with the exception, perhaps, alone of the Bartlow Hills, in Cambridgeshire, excavated by the late Mr. Rokewode. An interesting account of a discovery recently made by Mr. Neville, in the prosecution of his researches at Chesterford, was also contributed by Mr. Oldham. An olla had been brought to light, covered by a large dish of "Samian" ware, and containing a small vase, of rather unusual shape, in an inverted position amongst the ashes with which the large urn was filled.[31] In the "Museum Disneianum," there is a like example, as Mr. Disney stated to the meeting, of a large cinerary urn, enclosing a small one: these had proved, on anatomical observation, to contain the remains of an adult, and a very small child, respectively, supposed to have been a mother and her infant. These urns were found at Hanningfield Common, Essex.[32] Such deposits are not very usual; the Dean of Westminster is in possession of a large globular urn, or dolium, in which an olla of moderate dimensions was found enclosed. This discovery was lately made near Stratford-le-Bow. We hope to give a detailed account of Mr. Neville's discoveries in the next Journal.

A precious relic of ancient Irish art was brought before the Institute by the kindness of the Duke of Devonshire, being the enamelled pastoral staff, or rather the decorated metal case, enclosing a pastoral staff, supposed to have been used by St. Carthag, first Bishop of Lismore. Mr. Payne Collier, to whose charge this invaluable object had been entrusted by his Grace for this occasion, stated that it had been long preserved in connexion with the estates at Lismore, which had descended to him. Mr. Collier read the correspondence with the eminent Irish antiquaries. Dr. Todd and Mr. O'Donovan, expressive of the opinion that the date of the work, as indicated by inscriptions upon it, is A.D. 1112 or 1113, the year of the death of Nial Mac Mic Aeducain, Bishop of Lismore, for whom it appears to have been made. The name of the artist "Nectan fecit," is recorded in these inscriptions, which will form part of the Collections preparing for publication by Mr. Petrie. Some skilful antiquaries had been inclined to assign an earlier date to part of the decorations; this is not improbable, as relics of this nature in Ireland, long held in extreme veneration, were constantly encased in works of metal, which from time to time were renewed, or replaced by more costly coverings.

On a vote of thanks to the Duke of Devonshire being moved by Sir John Boileau, with the request that Mr. Payne Collier would convey to his Grace the assurance of the high gratification which his kind liberality had afforded to the Institute, Mr. Collier begged to express his conviction, by constant experience, that there is no possession of Literature or Art in his Grace's collections, which he is not most ready to render available for any object of public information, or for the advancement of science.

Mr. Westwood stated that there was much difficulty in determining the age of ancient objects of art, or MSS. executed in Ireland, owing to the isolation of that country, and the consequent long-continued prevalence there of conventional and traditional styles of ornament; thus, the triangular minuscule writing of the early ages has been continuous and is still used for writing the Irish language; whilst, in all the other nations of Western Europe, the early national styles were absorbed by the regular gothic. Still, however, slight modifications in the traditional styles of ornamentation were adopted, which, together with the inscriptions upon many of these ancient objects of art (in which occur the names of the parties by and for whom they were made), enable us to fix their date without any doubt, the ancient annals of Ireland (which have been in so many instances indirectly corroborated) affording very satisfactory means of identification of the persons mentioned in such inscriptions. This is the case with the Lismore crosier, and as there is no question that its entire ornamented metal covering is of one date, and that the inscriptions on it are also coeval, there seems no reason for doubting that its real date is the early part of the twelfth century, assigned to it by Dr. Todd and by Mr. O'Donovan. The "yellow cross of Cong," in the collection of the Royal Irish Academy, is also of the same date; a drawing of this was exhibited by Mr. Westwood, as well as figures of the pastoral staves of the abbots of Clon Macnoise, in the same collection, and the head and pomel of a crosier in the British Museum. The very similar ornamentation on the tomb of Mac Cormac, in the cathedral of Cashel, also affords additional means of judging of the date of the eleventh and twelfth century work in Ireland. The very short form of the Lismore crosier was alluded to and illustrated by a drawing of a small bronze figure of an ecclesiastic, in the same collection, found at Aghaboe, as well as by the figures of ecclesiastics on the ornamental cover, or cumdach, of the Irish missal formerly in the Duke of Buckingham's collection, now in that of Lord Ashburnham. The Lismore and Clon Macnoise staves were very remarkable for the row of dog-like animals on the outside of the crooked part. The former was, however, ornamented with small tessellated and enamelled ornaments, which do not appear on the Clon Macnoise crosier, but very similar details are found on a beautiful relic of unknown use in the collection of Mr. Hawkins, of Bignor Park, Sussex, a metal bason, found in the bed of the Witham, near Washingborough, and exhibited in the museum formed at Lincoln, as also, on this occasion, to the members of the Institute.

Mr. Westwood moreover thought, that the opinion which had been held, that the crosier contained within it the original simple wooden pastoral staff of the first bishop of Lismore, was correct, it being the constant habit of the Irish ecclesiastics to cover these relics with fresh ornamented metal work from time to time. Such is the case with the singular arm-like reliquary engraved in the Vetusta Monumenta; such are the various cumdachs; and such are the different portable hand-bells of the Irish Church, described by Mr. Westwood in the Archaeologia Cambrensis. Of two of the most highy ornamented of those relics full-sized coloured drawings were exhibited by him on the present occasion.

Mrs. Green communicated transcripts from several interesting letters connected with the eventful history of the latter part of the fifteenth century in England. They were recently found by her in a collection preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale, in Paris. These curious memorials will be given hereafter.

Mr. Ashurst Majendie, in presenting to the Institute a copy of the curious "Rapport au Conseil Municipal de Bayeux," by M. Pezet, on behalf of the Commission charged with the Conservation of the "Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde," in 1838, called attention to the singular fact, that in 1792 the tapestry had actually been taken to serve the unworthy purpose of a covering for a baggage-waggon. It was happily rescued, after the vehicle was on the route, by the spirited exertions of one of the citizens of Bayeux, who obtained some coarse cloth, which he succeeded in substituting for the venerable relic. The tapestry at a later time was removed to Paris, and exhibited in Notre Dame, to stimulate popular feeling in favour of the project of a second conquest of Albion.

The Rev. Joseph Hunter, in reference to the frequent notices recently communicated concerning Arabic numerals, offered the following interesting remarks on the earliest instances of their practical use in England.

He observed, that greatly superior as in every respect, and particularly for facilitating calculation, is the Arabic method of the notation of numbers above the Roman, it was not till a recent period that it superseded the mode which had been long in use. In the public accounts this notation was rarely used in England before the seventeenth century, and in private accounts the use of it is not at all common before that century.

Even stray and casual instances of the use of it, either entire or intermixed with characters in the Roman notation, are very rarely found in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. One has been observed by Sir Francis Palgrave, of the 10th year of King Edward the First, 1282. It is only the character for three; trium being written thus,—3um. See Parliamentary Writs, vol. i., p. 232.

Mr. Hunter laid before the Institute a fac-simile of a public document of the 19th year of King Edward the Second, 1325, in which the date of the year is expressed in one part in Roman numerals, and in another in Arabic. The document is a warrant from Hugh le Despenser to Bonefez de Peruche and his partners, merchants of a company, to pay forty pounds. Dated February 4, 19th Edw. II. (1325).

It is expressed as follows—"Hugh' le Despens' a nr'e bien amez Bonefez de Peruche & ses compaîgnons Marchauntz de la dite comp' . . . (torn) saluz, No'vo' maundoms q'de den's (deners) q' vo' auez du nr'e en garde facez liu'er a nr'e ch' compaignon Mons' . . . (torn) liures desterlinges questes no' lui auoms p'stez. Et voloms q' ceste Ir'e vo' soit garaunt de la h . . . (torn) le .iiij. iour de ffeu'er, Lan du regne le Roi Edward, fitz au Roi Edward, xixo." Indorsed—"Per istam literam solverunt Roberto de Morle militi. xl. li. i. per recogn' in cancellar' factam." And, in a different hand, on the dorse, is a memorandum of the payment, with a date February, 1325, as here represented. It is to be observed, however, that this indorsement is not written by an Englishman, but by one of the Italian merchants, to whom the warrant was addressed. Yet it shows that this notation was sometimes applied in England at the beginning of that century to purposes of business.

Sir Robert de Morle was much engaged in public affairs in the reign of Edward II., and was in various expeditions, t. Edward III., in France, where he died, in 1359. He acquired large estates in Norfolk by marriage with the heiress of le Marshall, in whose right he had also the Marshalship and lands in Ireland. The warrant here given seems to have been issued about the time when Queen Isabel with Prince Edward were in France, caballing against Edward II. and the Despenser faction. By distribution of great gifts amongst the French, a feeling unfavourable to Isabel was excited, and she left Paris for Hainault, whence she set forth in September following with a large force, and landed at Orwell.

The companies of Florentine and other Italian merchants were long encouraged in England, and supplied frequent loans to the Crown. (See Archæologia, vol. xxviii., p. 308.) The "mercatores de Societate de Perruch' de Florentia," occur 17 Edw. II., and subsequently; but the name of Bonefez does not appear in the numerous documents there cited.

Mr. Spencer Hall communicated a notice of sepulchral memorials of the family of Echingham, or Etchingham, accompanied by some architectural notes of the church of that name, in Sussex. He exhibited a curious series of sepulchral brasses. This Memoir is reserved for a future occasion.

Lieut. Walker, of Torquay, called the attention of the Society to the state of the ancient castle on St. Michael's Mount, Cornwall. A part of the foundation having been neglected has given way, and the building isconsequently in danger. It is stated that the proprietor (of the St. Aubyn family,) proposes to take down a portion in order to save the rest; it has, however, been affirmed, that this venerable structure might be preserved entire, by aid of buttresses or by underpinning the walls, and the interest attached to the castle appears to entitle it to every care.

The Rev. Dr. Nicholson, Rector of St. Albans, communicated an account of recent works of restoration in the Abbey Church, which have been carried on with the greatest care for the due preservation of that noble fabric. The stone used in the ornamental parts of the church is almost wholly from Totternhoe, where no quarry has been worked for many years. Dr. Nicholson, however, had fortunately purchased a large quantity in blocks, the foundation of an old barn, and probably once part of the conventual buildings. With this material he had completed many string-courses which were broken, hood-mouldings of arches, and other details which could, without risk of deviation from original authority, be replaced. The appearance of many parts had been greatly benefited by the removal of accumulated white-wash and paint. The floor and steps of wood, which disfigured the access from the south aisle into the choir, as also the unsightly wooden floor of the choir itself, have been suitably replaced by stone steps and a chequered floor; and the Saint's Chapel, as also Abbot Wheathampsted's Chantry, have been thrown open to view by the removal of a screen of modern wood-work which concealed them. The ancient decorative tiles have been brought together in the Saint's Chapel. Two of three large arches, filled up with rubble more than 3 ft. thick, and forming the east wall of the parish church on the Dissolution of the monastery, have been disencumbered of this mass, and a 9 in. wall substituted, so as to show their deep recesses. In this operation an altar, surrounded by mural painting, has been discovered, with a figure of an archbishop (S. Willielmus) in good preservation, assigned by Mr. Bloxam to t. Hen. III. This curious relic of art quickly faded on exposure, although Dr. Nicholson, with his customary vigilance, had caused it to be protected by glass. An engraving from this curious subject will shortly be produced. The original will still compensate the antiquary for the trouble of a visit to this interesting fabric, in the conservation of which Dr. Nicholson has shown so much judgment and good taste.

Antiquities and Works of Art exhibited.

By Mr. Charles Long.—Three "arrow-heads" of black silex, from the field of Marathon. They measure about an inch in length, and are now pointless, the edges sharp, one side is formed with two facets, the other is flat, so that the section would be a very obtuse-angled triangle. They were found in tumuli, and have been described by Col. Leake, who states that he found them likewise in other parts of Attica. The specimens exhibited were discovered by Mr. Henry Long, who called attention to the fact that Herodotus states that the points of the arrows, used by Ethiopians, in the armies of Xerxes, were of the stone with which they engraved their gems. He speaks also of another tribe who used stone-headed arrows.

Mr. C. Long exhibited also several silver coins, of Constantius, Valens, Valentinian, and Gratian, part of a hoard (about one hundred in number) discovered in the parish of Chaddlesworth, Berks, deposited in an earthen vase, of which a fragment only was preserved. The spot is on a bye-road about two miles north of the "Upper Baydon Road," which appears to be a continuation of the Ermine Street, leading from Corinium to Speen (Spinæ.) The old "Street Way" also runs about three miles to the northward, in the direction of Wantage. The discovery has been noticed in the Gentleman's Magazine. Mr. Long communicated a note of a mural painting discovered in September, 1849, over the chancel arch in Chelsworth Church, Suffolk. It represents the Day of Doom, the Saviour enthroned on the rainbow; the Virgin Mary at his right intercedes for the departed spirits; eleven Apostles, and various persons, some of them wearing crowns, appear behind her. On the left stands St. Peter, bearing the keys and a scroll. There is also a representation of Hell, with demons of grotesque forms, and the wicked tortured by chains worked by a windlace.[33]

By the Hon. Richard Neville.—Three remarkable bronze fibulæ, of the Anglo-Saxon period, from the Stowe Collection, two of them of the "saucer-shaped" type, and set with imitative gems. They are of large dimensions, diam. 314 in. The third consists of a circular ornament, chased and jewelled, appended to a long acus, and resembling certain ornaments found in Ireland. They were discovered at Ashendon, Bucks.

By the Rev. T. F. Lee.—Specimens of Roman and medieval pottery discovered at St. Albans. He presented to the Institute rubbings from a brass in St. Michael's Church, in that town, which had been concealed by pews, and that of Richard Pecock, 1512, at Redburn.

By Mr. Wiiincopp. — A metallic speculum, in remarkable preservation, discovered on the Lexden-road, near Colchester. It has a handle, according to the usual fashion of Roman mirrors; but objects of this kind have rarely been found in England. A small vase of fine "Samian" ware, exceedingly perfect, found at Colchester in 1848; the bottom, on the inside, bears the stamp ARC. OF. A very perfect cylix of brownish-coloured ware, with embossed ornaments; found in the Thames, Sept. 1847. A diminutive Roman vase, in singular preservation (height 212 inches), found in an urn at Colchester, 1837. A small vessel, or patera, of fine smalt-blue glass, found in an urn at the same place, apparently compressed by exposure to fire. A curious bronze armlet, with engraved ornament, several beautiful rings of various periods, with other ornaments of gold, and two silver armillæ of Anglo-Saxon workmanship. A standing cup, of ashwood (?) date about 1600; and some specimens of medieval pottery. A gold ring, with portrait of Charles I., inscribed C. R., 1648.

By the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.—A very curious carving in walrus-tooth, probably part of the binding of a Textus, or book of the Gospels. It represents the Saviour, within an aureola of the pointed-oval form, surrounded by figures of the Virgin, St. John, apostles, and angels. This specimen has been assigned to the eleventh century.

By Mr. Godwin, of Winchester, through Mr. Gunner.—A small carving in ivory, a roundel of open work, representing foliage and birds, probably of the thirteenth century. It was found in excavations in St. Thomas-street, Winchester, close to the site of the old parish church, now demolished. It was stated, that the workmen first met with a flooring of "encaustic" tiles, and on removing this there appeared beneath a pavement formed of large tiles, such as were used in Roman constructions. In the rubbish near this the ornament of ivory appeared, which very probably had been attached to some object of sacred use.

By Mr. Richard Hussey.—Several specimens, illustrative of ancient practices connected with architecture. They comprised a portion of the mortar formed of gypsum, without any use of lime, employed at St. Kenelm's Chapel, near Hales Owen; a specimen of tiles prepared for forming coarse unglazed pavements, resembling those of late Roman times; the quarry being cut through part of its thickness whilst the clay was soft, so that after firing it might readily be broken up into tessellæ of suitable size. This was found at Hartlip, Kent.—Also fragments from Danbury, Essex, showing the ancient use of terra-cotta in England for forming mouldings, as described by Mr. Hussey in the Journal (Vol. v., p. 34). They are flat portions, with a chamfered edge, so that several being arranged one over another, the angle of the chamfer alike in all, a set-off, or splayed surface, might readily be formed. Mr. Hussey presented also to the Society a small Sanctus, or sacring, bell, found during recent repairs at St. Kenelm's Chapel.

By the Rev. H. T. Ellacombe.—Sketches of two corbels, from the tower of Bitton Church, Somerset, sculptured heads probably intended to represent Edward III. and Queen Philippa. They were originally of good character, unfortunately now much impaired by exposure or injury, but interesting as contributing to fix the age of the fabric; Mr. Ellacombe considers the lower part of the tower to have been erected, circa 1377. He observed that very interesting series of regal portraits might be selected from sculptures of this kind, existing in various parts of England.