Balthasar Hübmaier/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII

THE SUPPRESSION OF THE MORAVIAN ANABAPTISTS

HÜBMAIER'S death was popularly likened to that of John Hus, and like the Bohemian leader, he was regarded as an innocent martyr—we have the word of his friend Faber for that. The evangelical Christians mourned the loss of a man of light and leading; Catholics rejoiced that one of their most formidable opponents had been for ever silenced. The testimonies borne to the rank of Hübmaier as an evangelical leader, praises of his learning and eloquence, are numerous, emphatic, and convincing. Kessler spoke of him as "the αρχικαταβαπτιστα of Nikolsburg," and he probably imagined that to be Greek, and to mean "chief Anabaptist." Vadian, the burgomaster of St. Gall, says that he was eloquentissimum sane et humanissimum virum (assuredly a very eloquent and cultivated man). Bullinger describes him as wohl beredet und ziemlich belesen gewesen aber eines unstäten Gemüts, mit dem er hin und her fiel (a man of good repute and become tolerably well read, but of an unstable disposition, through which he was much misled).[1]

As to the estimate of him by the Roman Church, the letter of Faber, written to two of his friends on the very day of Hübmaier's martyrdom, is a good example:

"As to Vienna, I can give you no news, except this one item: we must henceforth fight the plague of the Anabaptists. You already know how, after the destruction of one of their heads, numerous others straightway grow up! So their Dr. Balthazar, who has been a long time in prison because of his heretical doctrines, has now suffered the death penalty. We ought to hope that a large part of the heretics will vanish from the earth, so soon as an example has been made of the man who was the head of the Anabaptists and the inspirer of other criminals."[2]

THE TOWER OF THE CASTLE AT NÜRNBERG, IN WHICH ANABAPTISTS WERE IMPRISONED.

It would be useless to deny that the death of such a man was a heavy blow to the Anabaptist cause in Moravia, and to the Nikolsburg church in particular, but it was by no means fatal. Lord Leonhardt Lichtenstein and his brother were permitted in due time to return to their estates, and apparently continued their connection with the Anabaptists. It is certain that they could not be induced to do anything to persecute the brethren, even if they partially withdrew from them. But the death of Hübmaier was the signal for active measures to be undertaken against all Anabaptists by Ferdinand's Government, which the Moravian nobles might do nothing actively to help, but which, on the other hand, they dared not openly oppose. At the same time, they did what they could to discourage the more extreme and fanatical among the Anabaptists, and thus lessen the pretext for severe measures against them; though we do not again read of so energetic proceedings as the imprisonment of Hans Hut in the Nikolsburg Castle.

As the danger of a Turkish invasion became more pressing, in the summer of 1528 it became more and more a practical question among the Nikolsburg brethren whether a Christian man could lawfully take up arms in self-defence, or pay a war-tax for defence against this foe. The party that had agreed with Hübmaier became known as the Schwertler, or men of the sword; while their opponents were named the Stäbler, or men of the staff, i. e., of peace and non-resistance. Jacob Widemann was the leader of the Stäbler, and gradually the idea of community of goods became even more important in their eyes than opposition to the sword. It was at length with them the doctrine of a standing or falling Church, since they were firmly convinced that a true Christian brotherhood could exist on no other basis. Peace was not so much disturbed among the Nikolsburg brethren as made impossible, unless all would adopt the views of Widemann and make their practice conform thereto.

Lord Lichtenstein used every effort to induce greater moderation on the part of the Stäbler, and to restore unity in the brotherhood. He seems finally to have intimated that this faction must either be less contentious or leave his domains, and so they chose to leave. According to the chronicle, he rode with them to the boundary, drank a parting glass with them, and wished them God-speed. They went their way to Austerlitz,—a town about thirty miles to the north, near Brünn, the capital of the province,—in later years the scene of one of Napoleon's great victories. Here they established themselves.

The proprietors of Austerlitz were ready to welcome them and to afford them entire liberty. It is even said that waggons were sent to meet them at the boundary, where they had been dismissed by Lord Lichtenstein, and to help them on their way. They were given permission to build houses and to live their lives in their own way; and the experiment of an Anabaptist community was forthwith begun. For some years they suffered no interference, and so the experiment was conducted under most favourable conditions. The nobles were glad to encourage them, for population was sparse, labour was scarce, and apart from their religious notions the Anabaptists were known to be settlers of the most desirable sort, sober and industrious. The Austerlitz colony did not long remain the sole Anabaptist community: a colony soon went forth and settled at Auspitz, nearly midway between Nikolsburg and Austerlitz, and gradually others "swarmed," until there are said to have been by 1536 no fewer than eighty-six settlements, mostly numbering several hundred persons each, one being as large as two thousand. And in every case these communities seem to have enjoyed a uniform, steady prosperity.

Socialistic ideas often found advocates during the Reformation period, but here in Moravia was the most conspicuous, if not the only, instance of a practical experiment in the working out of these ideas. Jacob Huter is credited with the chief part in the organisation of these Moravian communities, for Widemann, though a born agitator and a would-be despot, proved himself to have no real gifts of leadership and organisation. Huter came to Moravia from the Tyrol soon after the establishment of the Austerlitz community, and for the next seven years spent much of his time there, permanently impressing his ideas of organisation on the communities.

The unit of all these communities was the "household," consisting in most cases of several hundred souls, all occupying a common building. Over each of these groups was a general superintendent, the "householder." The community idea was carried into all the details of living: the household had a common kitchen, a common bakehouse, a common brewhouse, a common schoolhouse, a common lying-in room, a common nursery, a common sick-room, and an order of "sisters" were nurses of the children and the sick. There was also a common dining-room, but in other respects each family lived its own separate life. [4] Clothing and bed-linen and such personal effects were treated as individual property, but all else was owned in common. There must necessarily have been much interference with personal liberty under such a system. For example, marriage outside of the community was strictly forbidden and was punished by instant expulsion. The young sisters who manifested some reluctance to marrying the only eligible suitors were virtually compelled to matrimony.

Economically the experiment was successful—as to that the testimony is ample and unanimous. There were no drones allowed in these busy hives, and there was no poverty. The socialist ideal of equal effort by all, and equal sharing by all in the fruits of labour, was fully realised. Industry and frugality, together with good management, had their reward, and the communities without exception became prosperous, not to say rich. It cannot be safely argued from this fact, however, that a general socialistic organisation of a nation would be economically successful; for these were a picked people in more respects than one, with much less than their due proportion of the aged and disabled and incorrigibly lazy, and far more than their proportion of able and willing workers.

Primarily these communities were agricultural. Their fields were the best cultivated and bore the largest crops in all the region. Moravia was then as now celebrated for its breed of horses, and those sent to market from these communities were esteemed the best and brought the highest prices. Men from these households were sought by the landowners of the region as managers of their farms, stables, vineyards, mills. But though primarily agricultural, the communities were skilled in the handicrafts also, and in a little time gained almost a monopoly of certain manufactures—as tailors, smiths, weavers, they had no superiors. The knives, scythes, shoes, stockings, bolting-cloths, handkerchiefs, and similar wares sent forth from these centres of industry were highly esteemed and eagerly bought. They were known to be honest goods, at fair prices.

Ecclesiastically, these communities differed from any others called Anabaptists. They had a chief pastor or bishop, an officer not found among others of the sect, and perhaps adopted from the Bohemian Brethren. Under this head there were in each community "ministers of the word" (generally, not necessarily, a plural eldership) and "ministers of necessities," or deacons. One of the ministers of the word was usually the "householder." Nobody might preach until he had been called to this office by the vote of the community, even though he had been an honoured preacher elsewhere, and this rule was rigidly enforced. The preacher was a man of much authority among them—indeed, he might easily become, and in too many cases actually was, a despot.

But though economically prosperous, these communities cannot be regarded as in other respects a satisfactory realisation of the Anabaptist ideal. Nor did they realise their own ideal of a perfect brotherhood; in proportion as the community prospered, the spirit of real brotherly love declined. Nowhere among Anabaptists, seldom anywhere among Christian people, has a more unlovely spirit developed. The selfish domineering of the "householder" preachers: the strife between those who wished to be preachers and those who, already occupying that office, refused to share their power with others; the murmurings and bickerings and jealousies among the members; the harsh intolerance shown to those who failed to abide by the community rules; the unchristian severity with which the excluded were treated—these and suchlike things have seldom been paralleled, and they are the harder to forgive since they were done in the name of a more perfect Christian brotherhood. All Anabaptists seem disposed to a reckless use of the "ban," but these communities alone would, in Christ's name, expel an erring brother and leave him to starve, rather than give him food or drink. Their Roman Catholic persecutors were not more cruel to these "brothers" than they were to each other.

The success of these socialistic Anabaptists, and the shelter given to them in Moravia for some years, led to a great immigration of the brethren from the surrounding regions. Historians, not too favourably inclined towards the sect, estimate the total membership of these groups as high as seventy thousand.[5] The noble landowners were glad to encourage their coming, for never had they been able to obtain labourers so satisfactory on their estates. Moravia was in that day, as in our own, one of the most fertile provinces of Austria, and it was experiencing a great access of prosperity in the growth of these Anabaptist communities. The testimony to the sober, law-abiding character of the people composing them is unbroken by any accusation of offence, even from their bitterest foes, save the form of religion that they professed and practised. This, however, was a continual offence, and the wonder is that they were unmolested so long.

The downfall of the communities began in 1535. By that time Ferdinand was sufficiently freed from his various embarrassments, chiefly immediate fear of the Turk, to permit him to give serious attention to matters never long absent from his thoughts—first among them the clearing of his dominions of all heretics. A fierce persecution was begun in the Tyrol, that ended in the martyrdom of Jacob Huter at Innsbruck, February 24, 1536, and the destruction or scattering of his followers. A simultaneous attempt was made to eject the Anabaptists from

A ROOM IN THE TOWER AT NÜRNBERG.

"It is a well-known fact that in the Netherlands the Anabaptists, committed to prison and held in subjection, have in the sequel begun to rebel against authority. Accordingly, neither Lutherans nor Zwinglians, nor, in fine, any sect, will suffer among them these heretics; it is, therefore, the will and intention of his Majesty not to suffer them any more in Moravia."[6]

Against their own wishes probably, against their own interests certainly, the Moravian nobles yielded to the royal command, and the Diet issued an order for the banishment of all Anabaptists. There was the less disposition to resist the royal policy, doubtless, because of the excesses that the Anabaptists were now committing at Münster. True, these people in Moravia had shown no such lawless and violent tendencies, but were they not also Anabaptists? And what might they not do if they had the opportunity? The argument was, at any rate, sufficiently plausible to silence objections and quiet tender consciences, if such there were among the persecuting party.

The landlords, who had hitherto given these groups willing harbourage, were now obliged to withdraw their protection and give notice to the "households" to leave their domains at once. Vainly did the innocent victims protest against this injustice; the utmost concession they could obtain was permission to take with them their movable property. The decree was executed by military force, pitilessly, and these unfortunate people were compelled to abandon the homes they had built, even the harvests they had sown, and find refuge where they might, in a region where every Government declared them outlaws. The dense forests of Moravia, the valleys in the mountains of Bohemia, gave them temporary hiding.

But, though scattered, they did not scatter in panic or disorder; there was a wise method in their flitting. They broke up into little groups, preserving their organisation, and wherever one of these groups settled, there was the nucleus of a new community. For a considerable time, therefore, though the persecution caused great personal distress and yet greater financial loss to the "households," it had little or no effect in diminishing their numbers. In fact, according to their chronicles, their numbers actually increased under the stress of this trial. Their meekness and patience in bearing this great injustice doubtless had due effect on the people, and won converts from those who might otherwise have been untouched.

In spite of the general spirit of meekness shown by them, there was one spirited protest against this cruel and unjust treatment. This took the form of a letter to Johann von Lipa, Marshal of Moravia, who had before this been one of their protectors, and had protested against the royal decree so long as protest was of any avail; and who now found himself in the hateful predicament of being compelled to enforce a decree of banishment against a people with whom at heart he sympathised. This protest, though probably from the pen of Huter, is written in the name of the entire brotherhood, and is the only official apology of the Anabaptists of this period.

"After these things we came into Moravia, and for some time have dwelt here in quietness and tranquillity, under your protection. We have injured no one, we have occupied ourselves in heavy toil, which all men can testify. Notwithstanding, with your permission, we are driven by force from our possessions and our homes. We are now in the desert, in woods, and under the open canopy of heaven; but this we patiently endure, and praise God that we are counted worthy to suffer for his name. Yet for your sakes we grieve that you should thus so wickedly deal with the children of God. The righteous are called to suffer; but alas! woe, woe to all those who without reason persecute us for the cause of divine truth, and inflict upon us so many and so great injuries, and drive us from them as dogs and brute beasts! Their destruction, punishment, and condemnation draw near, and will come upon them in terror and dismay, both in this life and in that which is to come. For God will require at their hands the innocent blood which they have shed, and will terribly vindicate his saints according to the words of the prophets.

"And now that you have with violence bidden us forthwith to depart into exile, let this be our answer: We know not any place where we may securely live; nor can we longer dare remain here for hunger and fear. If we turn to the territories of this or that sovereign, everywhere we find an enemy. If we go forward, we fall into the jaws of tyrants and robbers, like sheep before the ravening wolf and the raging lion. With us are many widows, and babes in their cradle, whose parents that most cruel tyrant and enemy of divine righteousness, Ferdinand, gave to the slaughter, and whose property he seized. These widows and orphans and sick children, committed to our charge by God, and whom the Almighty has commanded us to feed, to clothe, to cherish, and to supply all their need, who cannot journey with us, nor, unless otherwise provided for, can long live—these we dare not abandon. We may not overthrow God's law to observe man's law, although it cost gold, and body and life. On their account we cannot depart; but rather than they should suffer injury we will endure any extremity, even to the shedding of our blood.

"Besides, here we have houses and farms, the property that we have gained by the sweat of our brow, which in the sight of God and men are our just possession: to sell them we need time and delay. Of this property we have urgent need in order to support our wives, widows, orphans and children, of whom we have a great number, lest they die of hunger. Now we lie in the broad forest, and if God will, without hurt. Let but our own be restored to us, and we will live as we have hitherto done, in peace and tranquillity. We desire to molest no one; not to prejudice our foes, not even King Ferdinand. Our manner of life, our customs and conversation, are known everywhere to all. Rather than wrong any man of a single penny, we would suffer the loss of a hundred gulden; and sooner than strike our enemy with the hand, much less with the spear, or sword, or halbert, as the world does, we would die and surrender life. We carry no weapon, neither spear nor gun, as is clear as the open day; and they who say that we have gone forth by thousands to fight, they lie and impiously traduce us to our rulers. We complain of this injury before God and man, and grieve greatly that the number of the virtuous is so small. We would that all the world were as we are, and that we could bring and convert all men to the same belief; then should all war and unrighteousness have an end.

We answer further: that if driven from this land there remains no refuge for us, unless God shall show us some special place whither to flee. We cannot go. This land, and all that is therein, belongs to the God of heaven; and if we were to give a promise to depart, perhaps we should not be able to keep it; for we are in the hand of God, who does with us what he wills. By him we were brought hither, and peradventure he would have us dwell here and not elsewhere, to try our faith and our constancy by persecutions and adversity. But if it should appear to be his will that we depart hence, since we are persecuted and driven away, then, even without your command, not tardily but with alacrity, we will go whither God shall send us. Day and night we pray unto him that he will guide our steps to the place where he would have us dwell. We cannot and dare not withstand his holy will; nor is it possible for you, however much you may strive. Grant us but a brief space: peradventure our heavenly Father will make known to us his will, whether we are to remain here, or whither we must go. If this be done, you shall see that no difficulty, however great it may be, shall deter us from the path.

"Woe, woe, unto you, O ye Moravian rulers, who have sworn to that cruel tyrant and enemy of God's truth, Ferdinand, to drive away his pious and faithful servants! Woe, we say to you! who fear more that frail and mortal man than the living, omnipotent and eternal God, and chase from you, suddenly and inhumanely, the children of God, the afflicted widow, the desolate orphan, and scatter them abroad. Not with impunity will you do this; your oaths will not excuse you, or afford you any subterfuge. The same punishment and torments that Pilate endured will overtake you: who, unwilling to crucify the Lord, yet from fear of Caæsar adjudged him to death. God, by the mouth of the prophet, proclaims that he will fearfully and terribly avenge the shedding of innocent blood, and will not pass by such as fear not to pollute and contaminate their hands therewith. Therefore great slaughter, much misery and anguish, sorrow, and adversity, yea, everlasting groaning, pain and torment, are daily appointed you. The Most High will lift his hand against you, now and eternally. This we announce to you in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, for verily it will not tarry, and shortly you shall see that we have told you nothing but the truth of God, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, and are witnesses against you, and against all who set at nought his commandments. We beseech you to forsake iniquity, and to turn to the living God with weeping and lamentation, that you may escape all these woes.

"We earnestly entreat you, submissively and with prayers, that you take in good part all these our words. For we testify and speak what we know, and have learned to be true in the sight of God, and from that true Christian affection which we follow after before God and men. Farewell."[7]

The fierceness of this persecution soon declined, since there was no adequate local sentiment to sustain it, but it was again renewed in 1547, and from this time to Ferdinand's death, in 1564, was a period of suffering known in the Anabaptist literature as "the time of the great persecution." The reign of Maximilian II. (1564-1576) and the first half of his successor's reign (Rudolf II., 1576-1612) was a time of comparative freedom from molestation, and is called in the chronicles "the good time of the church." Once more their communities flourished, under the protection of the Moravian nobles, who successfully withstood the occasional demands of Austria's rulers that the Anabaptists should be driven out of the land.

In the meantime Nikolsburg had continued to be, in some sort, the headquarters of the Anabaptists. The House of Lichtenstein had not ceased to grant them countenance and protection, so far as possible, nor is there any hint that Lord Leonhardt ever withdrew from the body. There does not seem to have been any radical change in the attitude of the House towards the brethren during the lifetime of his son, Christopher, though it is not known that the latter was a member of the body. The Lichtensteins, and for the most part the other Moravian nobles, pretty uniformly returned a non possumus to all their monarch's edicts of persecution; and, if they did not openly protest, their capacity for passive resistance was practically unlimited. Unless the Austrian Government was prepared to send soldiers into Moravia, little could be done towards the dispersal of the Anabaptists.

But with the death of Christopher von Lichtenstein, in 1572, a marked change came over Nikolsburg. He left no heir,[8] and the estates, therefore, reverted to the Crown; and in 1576 the Emperor sold them to Adam von Dietrichstein, whose descendants, subsequently raised to princely rank, still hold them. The new lord of Nikolsburg belonged to a distinguished Romanist family, one of whom was later Bishop of Olmütz and a Cardinal. It was not to be expected that a man of such antecedents, known himself to be an ardent Catholic, should tolerate in his domains those who were so much despised and contemned by the Church as

INTRUMENTS OF TORTURE AT THE TOWER OF NURNBERG.

There were at this time in Nikolsburg and adjacent towns 3720 persons known or reputed to be Anabaptists. A historian of the period records the success of Dietrichstein's efforts to purify the region. Nikolsburg had been the refuge of all sorts of pernicious heretics, who had so flourished as to give the town a bad name everywhere. It had passed into a proverb: "He is from Nikolsburg, therefore he is an Anabaptist." Dietrichstein brought to pass in a few years so great a change that it might be said with equal truth: "He is from Nikolsburg, therefore he is a Roman Catholic and Jesuit Christian."[9]

This is, however, the usual and perhaps pardonable exaggeration of the eulogist. The new lord, like the proverbial new broom, swept clean—as clean as he could—but he did not accomplish so complete an alteration in the character of Nikolsburg as the partial historian represents. His successors were less given to the policy of "Thorough," and the Anabaptist chronicles contain proofs in plenty that these repressive measures were only partially effective. No longer could the brethren be said to flourish in Moravia, but they still endured. The seventeenth century, however, was to witness their all but complete destruction. The Jesuits had obtained the ear of the Austrian Court, and had established their emissaries in important ecclesiastical posts throughout Moravia. The motive power for steady persecution was thus supplied; against their persistent malignity and sleepless vigilance no heretics might long stand.

In 1623 a new royal decree for the persecution of Anabaptists was issued through Cardinal Dietrichstein, and from this time forward there was little intermission of severity. Prince Liechtenstein, now a Roman Catholic and Marshal of Moravia, was active in the work, which was part of the reactionary policy of the Thirty Years' War wherever the Austrian and Imperial power extended. In this terrific persecution many thousands perished—there is no adequate and trustworthy record of the number. A list in one of the chronicles, drawn up about 1581, gives the number of martyrs among the brethren up to that time as 2169, but this is only a small fraction of the number who lost their lives for the truth's sake before the persecution was ended. Another chronicle thus describes their sufferings:

"Some were torn to pieces on the rack, some were burned to ashes and powder, some were roasted on pillars, some were torn with red-hot tongs, some were shut up in houses and burned in masses, some were hanged on trees, some were executed with the sword, some were plunged in the water, many had gags put into their mouths so that they could not speak and were thus led away to death. Like sheep and lambs, crowds of them were led away to be slaughtered and butchered. Others were starved or allowed to rot in noisome prisons. Many had holes burned through their backs and were left in this condition. Like owls and bitterns they dared not go abroad by day, but lived and crouched in rocks and caverns, in wild forests, in caves and pits. Many were hunted down with hounds and catchpoles."

By means of such measures, the number of Anabaptists in Moravia was sensibly decreased; most of the brotherhood who survived these fiery trials found a home elsewhere. The depopulation of the country, owing mainly to these persecutions, was so frightful that the Diet passed a special statute giving to every man in Moravia the extraordinary privilege of taking two wives, that the country might be repeopled![10] Nevertheless, even so a remnant of the brethren survived and continued to live in the province, in ever-diminishing numbers, for at least a century longer. Some found refuge in Bohemia and Hungary, where a few colonies are said to survive until this day. One group made their way into southern Russia, where they remained until 1874, when they emigrated in a body to South Dakota, and there, in several communities, they seem to be renewing their former prosperity. Even in Moravia itself it is doubtful when they became entirely extinct, for traces of them were found by Dr. Beck as late as the year 1815; but no community is known to exist there now. [11]

In the sequel, therefore, we see the almost complete destruction of the fabric that Hübmaier and his associates reared with so great effort and at so costly sacrifice. The traces of them and their labours disappeared as utterly as the wake of a vessel in the ocean. Shall we, therefore, declare that they lived and laboured in vain? Did such as Hübmaier give their lives for naught? Not so. Hübmaier's contribution to the gradual progress of the truth, to the slow emancipation of man, to the final triumph of religious and civil liberty, was not only considerable but lasting. His name, his example, and his teachings were long cherished by the brotherhood; and when his name and example had faded from recollection, his teachings lived on. In an age of credulity and superstition he stood for the gospel proclaimed by the Apostles. Among people groaning under the exactions of an effete feudalism and oppressed by despotic and selfish princes, he advocated justice and mercy on the part of rulers, sobriety and obedience on the part of subjects. At a time when intolerance and persecution were universal, his was the voice of one crying in the wilderness for restoration of the God-given right of every man to study the Scriptures for himself, and to follow whithersoever they might lead.

"TRUTH IS IMMORTAL"

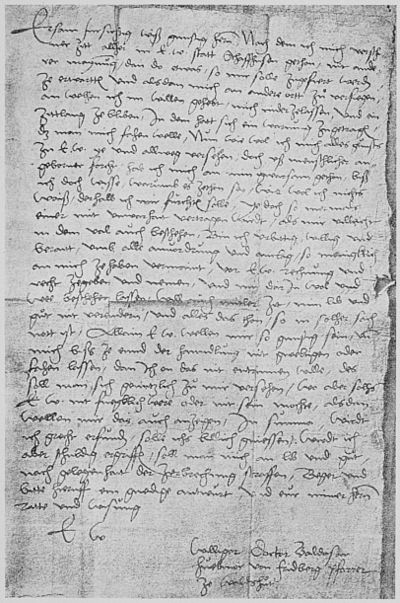

FACSIMILE OF HUBMAIER'S FIRST APPEAL TO THE COUNCIL OF SCHAFFHAUSEN.

ORIGINAL IN THE SCHAFFHAUSEN ARCHIVES.

- ↑ One of the Anabaptist chronicles speaks of him as in Latenische Grichischer und Hebräischer sprach wol erfaren. Beck, Geschichts-Bücher, p. 52. But we have seen reason to conclude that his acquirements in Greek and Hebrew were limited.

- ↑ Quoted by Loserth, p. 157.

- ↑ In the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, drawn up in 1619 for the Spanish Inquisition by Archbishop Bernhard of Sandoval, he is named four times: Balthasar Pacimontanus, Balthasar Hubmaier, Balthasar Hilcmerus, Balthasar Isubmarus. His name stands fourth among the hereticorum capita aut duces, preceded only by those of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. Schwenckfeld is the only other heretic named.

- ↑ This "household" is an anticipation of the phalanstery of Fourrier, so complete in its details as almost to justify a suspicion that some account of these Moravian communities had become known to the French economist.

- ↑ Hast, Geschichte der Wiedertäufer, p. 212.

- ↑ Quoted by Heath, Anabaptists, p. 75. Similar edicts, of various dates, are given in the chronicles. Beck, Geschichts-Bücher, p. 177 et al.

- ↑ This document is given by Ott, Annales Anabaptistici, pp. 75-78, and in several other collections of Anabaptist documents. There can be no doubt of its genuineness. The above translation, with some changes, is from the Martyrology of the Hansard Knollys Society, i., 149-153.

- ↑ A younger branch of the family remained Protestant through the sixteenth century, in spite of the severe persecutions to which all were subject who resisted the Roman Church. About 1604, Count Charles Lichtenstein became a convert to the Catholic faith, and was rewarded by being raised to the rank of Prince in 1608, and in 1621 was made Regent of Bohemia. The family has ever since remained one of the most distinguished and powerful in Austria, and possesses large estates in various parts of the Empire. Only a few miles from Nikolsburg are the castles of Feldsburg and Eisgrub, still owned by Prince Liechtenstein (to use the modern orthography), the latter situated in the midst of a magnificent park of over a hundred square miles. The family has in recent years risen to royal rank, for since 1866 Liechtenstein has been an independent principality—one of the smallest kingdoms in Europe, with an area of only sixty-five square miles and a population not exceeding ten thousand souls, situated between the Tyrol and Switzerland. But a king is a king, even if his kingdom is no larger than a pocket-handkerchief!

- ↑ Christopher Erhard, in Sampt angetruckten Gespräch, Ingolstadt, 1586, p. 31. Quoted by Loserth, Communismus, p. 55.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, art. "Moravia," historical sketch.

- ↑ It has not been thought necessary to give authorities for most of the several statements of this chapter. The materials are derived, about equally, from Loserth's continuation of his biography of Hübmaier, Der Communismus der Mährischen Wiedertäufer, Wien, 1894, and Beck's Geschichts-Bücher.