Burmese Textiles/Section 1

The Geographical Situation of the Shan States.

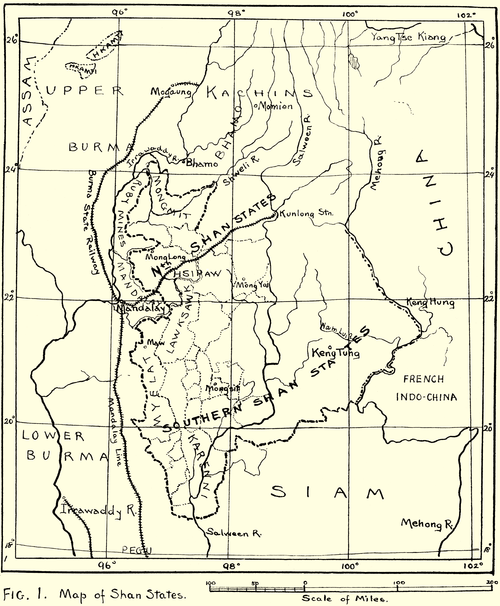

The country between Assam and China is the point from which a number of great rivers, the Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Salween, Mekong and Yang-Tze start southwards in parallel courses, finally spreading out into a fan shape which covers the country from the Yellow or China Sea, to the Bay of Bengal.

The rivers run in deep, narrow channels, separated by mountain chains which also run in the same direction, north and south. These ranges, at first sharply defined, gradually widen out and the river valleys widen also, until, with their tributary streams, they form a series of flat bottomed valleys, leaving between the Irrawaddy and the Salween (Fig. 1) a plateau, between 2,000 and 3,000 feet high, known as the Shan plateau.

The Shan States extend eastward beyond the Salween to the Mèkong, which forms the boundary between them and French Indo-China for about 100 miles. The area of these States has been estimated at between 40,000 and 50,000 square miles and, roughly speaking, may be said to lie between the 19th and 24th parallels of latitude, and the 96th and 102nd of longtitude. Their shape is approximately that of a triangle, with its base on the plains of Burma and its apex on the Mèkong River (Fig. 1).

The Salween runs almost centrally through the British Shan States. Its mountainous banks have always formed a serious barrier; so that the branches of the Tai or Shan race on either side differ in name, dialect, written character and costume.

The History of the Shans or Tai.

The Tai or Shan race is the most widely spread of any in the Indo-Chinese peninsula, and it is also the most numerous. It extends beyond the peninsula for the Li, who inhabit the interior of Hainan, are almost entirely pure Tai, having similar tribal customs to the Shans and a written character very like theirs.

Siam is now the only independent Tai State in existence, and of the people occupying that district previously to A.D. 1350 there is no record.

The remaining Shan tribes inhabit the Northern and Southern Shan States, the Tai Mao or Chinese Shan and the Burmese Shan districts.

Burma is under the political control of the Government of India and is ruled by a lieutenant-governor. For administrative purposes the country is divided into two parts, Upper and Lower Burma, and the Shan States are treated as semi-dependencies under the Commissioner for Upper Burma. Although, therefore, no part of Burma can be said to be under native rule, the petty chieftains in the Shan States and in the Chin, Arakan and Kachin hills have considerable influence over their sometimes turbulent followers.

The Tai race formed the dominating power in Yünnan for many centuries, and their migration into Burma probably began 2,000 years ago. These first movements were most likely due to restlessness of character, but later, larger and more important migrations were due to the pressure of Chinese invasion and conquest.

Most Northern Shan chronicles begin with the legend that, in the middle of the sixth century, two brothers descended from heaven and took up their abode in the valley of the Shewli, or the Irrawaddy, or some other valley in which local pride desires to place the settlement; there they found a people which immediately accepted them as Kings.

A great wave of immigration certainly did descend from the mountains of Southern Yünnan into the Shewli, or Nam-Mao valley, in the sixth century, and this legend is the folks-myth fashion of stating an historical fact. At any rate all traditions and chronicles so far discovered assert that the Shewli valley and its neighbourhood was the first home of the Shans in Upper Burma. (The Shewli river is an important tributary of the Irrawaddy, flowing in from the Shan States and China.)

From this valley the Shans spread south-east over the present Shan States, north into the Hkamti region (Fig. 1) and west of the Irrawaddy into all the country lying between it and Assam, finally, some centuries later, 1229, conquering that country also.

About the end of the thirteenth and during the fourteenth centuries, wars with China and Burma were frequent and caused great loss. There was no central Shan power, the various principalities possessing semi-independence, and of these Mong Kawng (Mogaung) was the farthest from China, and seems to have been the most powerful.

Chinese invasions in A.D. 1582 and 1604 put a final end to the Mao Shan dynasty, and Shan history then becomes merged in Burmese. The Shan principalities, although restive under the rule of Burma, never threw off the yoke.

The town of Mogaung still bears every appearance of having once been a large and thriving centre, much bigger than Bhamo. It suffered greatly in wars with Burma in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and its sack by the Kachins in 1883 would have brought permanent ruin had it not been for the British annexation in 1886.

The Appearance of the Shans and their Dress.

The Shans resemble both the Siamese and Burmese in general appearance, but are frequently fairer. They are muscular and well formed, having eyes almost lineal in position, a small nose and a large mouth. Their hair is long, lank and black, and they practise tatu.

The dress of the men generally consists of a pair of trousers and a jacket, the pattern of the former varying considerably amongst different tribes, sometimes being like the Chinese with well-defined legs, sometimes, especially among the well-to-do classes, being so voluminous as to look like a skirt. White turbans are worn in the North, variously coloured ones in the South, whilst the Chinese Shan wears blue and the Shan trader of British territory a broad-brimmed, limp, woven grass hat of Chinese manufacture (Fig. 2).

The men usually tatu with isolated patterns in red on the chest, back and arms, in some cases continuing the tatuing as far as the middle of the calf.

The Shan women (Fig. 3) do all the indoor and much of the field work, they are strong, healthy, and fair-skinned; being fine specimens of Eastern female beauty.

They wear a skirt consisting of a straight length of cloth fastened by a half-hitch at the waist so that the opening falls at the side, GS 17 (Fig. 17), GS 15 (Fig. 20), GS 21 (Fig. 21). In some cases the length of cloth is joined up so that the skirt is closed, GS 62 (Fig. 15), GS 24 (Fig. 22). Jackets are worn by some tribes, GS 57.

(WEAVING, pp. 8, 9.)

The Shans are seldom found away from the alluvial basins and do not regard themselves as hill people. They are good traders, though only on a small scale, but since the pacification of the country under British rule the volume of traffic has steadily increased. Everywhere cultivation is more careful and laborious than in Burma. Rice is the chief crop, but cotton, tobacco, leguminous crops and ground nuts are grown in most parts, and in certain special districts tea, sugar-cane and chillies are cultivated. Rice is exported in large quantities, and cotton to China in a lesser degree.

The Arts of Weaving and Dyeing, with a note on Native Design and Methods of Decoration.

Although at the time of writing foreign cloths are being imported to a certain extent into the Shan States, it is the custom for all Shan women to weave cloth for their own garments and those of their families. All the cloth used in the garments forming the George Collection are of native manufacture with the exception of some used entirely for decorative purposes, such as the red flannel, GS 58 (Fig. 9), GS 23 (Fig. 16), GK 8 (Fig. 38), and some Chinese silk brocade, GS 24 (Fig. 22).

The cotton from which the cloths are made is grown locally and prepared by the women. The date of the introduction of the cotton seed into Burma is unknown, but Mr. G. F. Arnold relates how "The Shans tell of eight Brahmas, four male and four female, who came down long since from above, and eating of the earth became human. Denied a return to heaven, they took up their abode in Burma, and, multiplying there, introduced among the people the cultivation of cotton, and the arts of spinning and weaving."

It is most probable that cotton was introduced from India, where it was used at a period much earlier than there is any record of its use in China. Notwithstanding the length of time for which cotton has been cultivated in the Shan States, and Burma in general, the methods employed in weaving are still very primitive.

In Shan villages nearly every house has a loom, made sometimes of bambu, sometimes of heavy wood, and generally kept on the ground in the open space beneath the living rooms.

The raw cotton is prepared by drying the balls in the sun, extracting the seeds by passing them through the usual small two-roller gin, and then opening it out by catching the partly cleaned cotton up from the revolving basket in which it is placed, by means of an instrument shaped like the bow of a violincello (Fig. 4a, p. 5). After the cotton fibres have been separated in this way, they are made into slivers and wound round a stick about eight inches long and three-quarters of an inch thick, from which the cotton is converted into thread by a form of spinning jenny. The thread is wound into hanks, soaked in rice water to give it firmness, and placed in the sun again to dry.

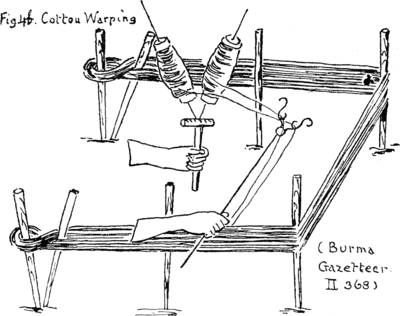

The natural comb on the inside of the fruit called "Satthwabin," which, when dry, is somewhat like a sponge, is used to make the threads more even before being wound on bobbins. The web is next warped by winding the skein off two hand-reels round four short posts fixed firmly in the ground, from twenty to thirty feet apart, according to the length of stuff to be woven (Fig. 4b). When sufficient has been wound the web is lifted off, carried to the loom and beamed. The arrangement of the warp is similar to that described as in use in Syria in Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms[1] except that it is tied to a beam instead of being weighted.[2]

The cloths are narrow, seldom exceeding fifteen inches (38 cm.) in breadth and often being narrower. In many of the heavier ones the effect of a poplin or repp weave is produced by having about three times as many warp threads to the inch than there are weft. This results in the warp forming the surface of the cloth and, of course, minimises the amount of labour.

A Shan woman can weave about five yards of this plain cloth in a day and, unless there is to be a design, the yarn is not dyed but the complete cloth is soaked in an infusion of the indigo.plant, dried, washed and steeped again until the result is sufficiently dark in colour.

Pattern Weaving and the Materials Used.

The weaving of patterns, of which there are an endless number, is performed by passing several shuttles with threads of different colours at intervals along the web. This is a form of "brocade or inlay weaving," and it is probable that, like the cotton plant, it was introduced from India, where even the elaborate patterns of Cashmere shawls were produced by this method, from four to fifteen hundred needles taking the place of the shuttles. In brocade weaving each separate piece of design has its own shuttle which is worked backwards and forwards to the shape of the ornament between the picks of the plain weft. In order to obtain the best effect, the brocading weft is usually passed only under one or two warp threads and over a much larger number, varying according to the patterns, GS 21. The number of ordinary picks between each line of brocading also varies, thus throughout GS 21 (Fig. 21) there are two picks between, whilst in GS 15 the number varies from one to four and thus directly influences the width of the pattern (Fig. 20).

Such a process requires great care and skill on the part of the person weaving, and a space of several minutes sometimes elapses while the numbers of little shuttles [or bobbins] are passed along the breadth of the web.

Dyed spun silks, both twisted and non-twisted (floss) are used in working the patterns on the Shan cloths, but dyed cotton is chiefly used by the Kachins for the same purpose, with a resulting dullness ot colour.

In the patterns on some of the Kachin bags and for the stripes on GS 55n, a fine, silvery, natural, non-spun grass fibre has been used with good effect. On the bags it has been dyed but still retains its lustre. In many of the finer pieces of work the whole gamut of Oriental colour known as "the perfect seven" is used, indigo, porcelain blue, green, yellow, orange, rose and red; relief and general harmony are also sometimes accentuated by an outline as in GS 17 (Fig. 17).

Designs.

Mr. George considers that many of the patterns are traditional, and that "the Shan designs of the nineteenth century are probably identical with those of the fourteenth, and are still modifications of the lozenge, square, fret and stripe."[3] The combinations and variations of these elementary forms are endless, and the cloth ground is frequently covered with most intricate patterns made up from these motives; GS 15 (Figs. 20, 20a), GS 21 (Fig. 21), GS 86 (Fig. 25), GS 15a (Fig. 26), GK 39a (Fig. 34).

In nearly all the work that universal motive "the swastika or fylfot" can be found, generally with its arms going from left to right, GK 39a (Fig. 34a), but also sometimes in the opposite direction GS 15 (Fig. 20a), GS 15a (Fig. 26).

Judging from the patterns on the cloths in the collection, there are certain differences between the Shan and Kachin use of the swastika and fret. Generally speaking the swastika is found by itself in the Shan cloths, GS 15 (Fig. 20a) although more elaborate patterns may be derived from it, but in Kachin cloths it is usually surrounded by a border GK 39a. (Figs. 34a and 34b).

The fret is used by itself amongst the Shans, or as a running border (Fig. 20a) and in groups, frequently of three, by the Kachins. The latter arrangement is most unusual, and does not appear on any but Kachin cloths, GK 39 (Fig. 33), GK 39a (Figs. 34, 34a), GK 8 (Fig. 38). Many other developments of the fret can be traced in the Kachin cloths and in the decorations of some of their wallets, GK 5 (Fig. 39).

The patterns in Kachin designs seem to be nearly always worked upon a basis of squares, whilst the Shan patterns have the lozenge as a foundation. GS 21 (Fig. 21) is an exception to this generalisation, but is not a typical Shan design.

Representations of animals and birds, common in Persian, Chinese, Japanese and Indian work, are scarce in Shan and Kachin decoration. The representations of a dog in the borders on several of the Kachin bags, GK 1 (Fig. 35a, b, c), GK2 (Fig. 37) and GK 3n and the peacock in GS 17 (Fig. 17) are the only examples which occur in this collection.

Shan waistbands and head-dresses frequently have a series of borders at the end, GS 15a (Fig. 26), GS 22 (Fig. 27) GS 55n; and the patterns on skirts run in a series of vertical stripes, narrow as though compressed, GS 15 (Fig. 20).

Kachin Cloths.

The cloth manufactured by the Kachins is of a coarse but strong texture, the thread being dyed previously to being woven. Two forms of loom are in use, one similar to that described as in use by the Shans, the other much more primitive. In the latter, one end of the warp is held in position by pegs driven into the ground, the other fastened on to a breast beam, the whole being kept taut by means of a broad leather belt fastened round the back of the woman weaver as she sits on the ground. A shed stick is evidently used, but whether the weft thread is carried by a shuttle or a spool is not clear. Anderson[4] says "the tool is thirty inches long," so it is probably a spool.

A strong, thick, narrow cloth is produced into which patterns are woven in Indian red, brown, green, yellow, white and black, the body of the cloth being frequently of a reddish brown or terra cotta colour, GK 39, GK 3ga. Occasionally the warp is arranged in coloured stripes, and as, owing to the slackness of the work when in progress, the warp largely forms the surface of the cloth, these stripes have a marked influence upon the patterns which cross them, GK 39 (Fig. 33b and c).

The Kachins are adepts at embroidery in silk and cotton, and their skill is often to be seen in the wallets carried by them. In the art of dyeing they are not so skilled as the Shans and their more limited range of colour is very noticeable.

Dyeing and Dyes.

H. G. A. Leveson, in the Upper Burma Gazetteer gives an account of the dyes used in the Shan States of which the following is an extract:—" Dyeing as an industry is seldom the sole objection of an individual or household. With the exception of indigo, which is cultivated in odd corners of vegetable gardens, the majority of plants used for dyeing are found wild.

The cloths are, for the most part, home-dyed and the results depend on chance and the fancy of the operator.

Indigo. Two varieties of plants are recognised, both give an equally good dye varying from blue to black.

Sticklac is cultivated generally in the Karenni district (Fig. 1); elsewhere if a tree is attacked the deposit is cultivated when it is formed. It gives a crimson dye.

The other dyes are not produced in large quantities, but the following are the chief:—

- Purplish Red is obtained from the heart wood of the sappan tree.

- Terracotta from the root of the niba plant,

- Bright Red from the root of the mai hsalak tree.

- Red from the berry of the mak hpawag.

- Yellow from turmeric roots dried and pounded.

- Yellow from the roots of the saffron plant.

- Light Blue from the bark of the 'green bark' tree.

Light Green is obtained by a combination of the blue with saffron.

Many of the dyes mentioned are used in connection with each other and with indigo. Various shades of green are produced by using different proportions of indigo with turmeric or saffron, and of purple and orange with these and niba or hsalak."

Mr. T. H. Giles says that "the Karenni women use the leaves, bark and roots of the dankyat as mordants for fixing crimson, the fruit of the Phyllanthus embelia, the fruit of the paw, a species of the terminalia genus of plants, and the fruit of the hog plum are all used for fixing green and yellow."

Although exquisitely soft colours are obtained by the use of these dyes, aniline colours are being imported more and more into the country, and are used as far east as Kengtung. They are gradually superseding the native productions, although some trade is done in cutch, sticklac and sappan wood with the Burmese.

Methods of Decoration other than pattern weaving.

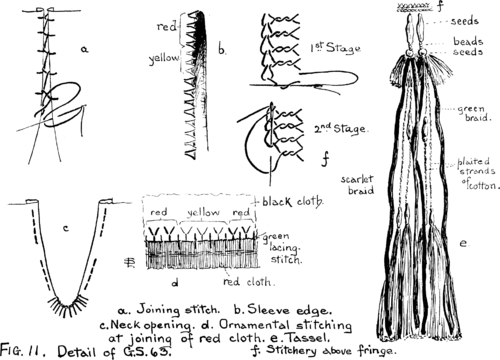

Amongst the examples of Shan and Kachin garments in the George collection other methods of decoration besides brocade weaving are to be found; of these, embroidery, appliqué of different materials to form patterns, and the addition of fringes and tassels form the chief.

The embroidered decorations fall into three classes:—

Dyed cottons and silks are the materials chiefly used in the embroidered decoration.

Panelled borders formed of various imported stuffs, scarlet flannel from England, silk and metallic brocades from China, are a form of appliqué popular as a skirt trimming (Fig. 3), GS 24 (Fig. 22). Variously and beautifully dyed native cloths are also arranged to form elaborate appliqué patterns of which the borders on GS 60 (Figs. 13, 13a, 14), and GS 23 (Fig. 16), are excellent examples. An exceedingly interesting development of this form of decoration is to be seen in the skirt GS 24 (Fig. 22), where below the deep panelled border there is a narrow pattern worked out in small folded pieces of cloth (Fig. 23).

In addition to the materials already mentioned, white seeds, known as Job's tears (Coix Lachryma Jobi, L. var. stenocarpa), GS 57 (Fig. 7), GS 32 (Fig. 29), GK 8 (Fig. 38), and GS 43, 44, 45, (Fig. 28,) cowrie shells, GS 23 (Fig. 16), iridescent beetle bodies (Fig. 28), plaited braids GS 57 (Fig. 7), GS 59n, and gold foil, GS 15 (Fig. 20a), GS 22 (Fig. 27) are also used.

Fringes and elaborate tassels are also important factors in the schemes of decoration. True fringes are developed from the warp ends by twisting and knotting, as in GS 59 (Fig. 8), GS 13 (Fig. 24), and GS 86 (Fig. 25), or have added threads to form a tufted edge such as GS 57 (Fig. 7), others again are made up of a number of tassels, GS 63 (Figs. 10, 11e). The chief note of decoration in many of the Kachin wallets is provided by tassels, GK 8 (Fig. 38), GK 5 (Fig. 39), which are often elaborately built up from plaited and twisted cords, and scarlet and white braids ornamented with beads, white seeds, tufts of coloured threads and tabs of scarlet flannel or other coloured cloth GS 13 (Fig. 24). Tasselled lappets are also worn as ear ornaments (Fig. 31c).

The strikingly good effects obtained by the use of such simple materials, and the foregoing methods of decoration compel the admiration of anyone who sees the cloths.