Cassell's Illustrated History of England/Volume 1/Chapter 48

CHAPTER XLVIII.

Richard set sail from Acre in October, 1192, with the queen Berengaria, his sister Joan, and all the knights and prelates who held fealty to the English crown. The proud heart of Cœur-de-Lion would not permit him to visit Jerusalem in the lowly guise of a pilgrim, but he quitted Palestine with feelings of the deepest regret; and he is reported to have stretched out his arms towards the hills, exclaiming, "Most holy land, I commend thee unto God's keeping. May he grant me life and health to return and rescue thee from the infidel!"

A heavy storm arose—attributed by the sailors to the displeasure of Heaven—and overtook the returning fleet, scattering the ships, and casting many of them ashore on the coasts of Barbary and Egypt. The vessel which carried Joan and Berengaria arrived in safety at a port in Sicily. Richard had followed in the same direction, with the intention of landing in southern Gaul; but he suddenly remembered that he had many bitter enemies in that country, in whose power it would be dangerous to trust himself, and he turned back to the Adriatic, dismissing the greater part of his followers, and intending to take his way homeward in disguise through Syria and Germany.

His vessel was attacked by Greek pirates; but he not only succeeded in repelling the attack, but in commanding their services to convey him to shore. Possibly, his name may have had an influence, even with these robbers of the sea; but, whatever were the means employed, it is certain that they placed themselves under his orders, and that he quitted his own ship for one of theirs, in which—the better to secure his disguise—he proceeded to Zara in Dalmatia, and there landed. He was attended by a Norman baron, named Baldwin of Bethune, two chaplains, a few Templars, and some servants. Richard had assumed the dress of a palmer, and, having suffered his hair and beard to grow long, went by the name of Hugh the Merchant. He had however, not yet learned prudence, and those who were with him seemed to have been as deficient in this quality as himself.

The Bishop of Salisbury before Saladin.

It was necessary to obtain a pass of safe conduct from the lord of the province, who, unfortunately, proved to be a relation of Conrad of Montferrat. The king sent a page for this purpose, desiring him to ask a passport for Baldwin of Bethune and Hugh the Merchant, who were pilgrims returning from Palestine, and ordering him to present to the governor a large ruby ring, which Richard had purchased in Syria from some Pisan merchants. Some of the chroniclers relate that the lord of Zara recognised the ruby, which was a famous stone; but in any case, his suspicious were excited by seeing so valuable a jewel in the hands of men who professed themselves of such low degree. "This ring is the present of a prince, not of a merchant," he said to the messenger. "Thou hadt not told the truth; thy master's name is not Hugh: he is King Richard. But since he has sent me the gift without knowing who I am, tell him from me that I give him back his present, and that he may go in peace."

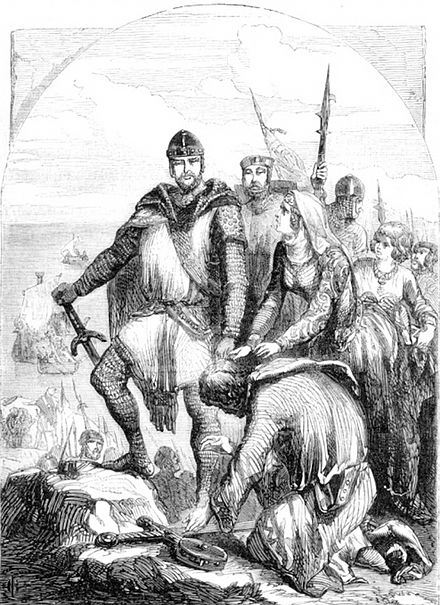

Richard Cœuer-de-Lion suprised by the Artisan Soldier.

At this unexpected discovery the king did not hesitate to avail himself of the permission he had received, and, having obtained horses, he quitted the town on the same night. But the governor had no intention of permitting his enemy to escape from the country. He sent off messengers to his brother, the lord of a neighbouring province, to inform him that the dreaded King of England was about to pass through his territory in disguise. Among the retainers of the brother was a Norman knight named Roger, who was employed to go to all the taverns which received travellers, for the purpose of discovering the royal fugitive. For several days the Norman pursued his search without success, but he was stimulated by a vast reward which was promised him, and at length he discovered the king. No sooner, however, did Richard confessed who he was, than the ties of country and the duties of allegiance to his native sovereign overcame the love of money in the breast of the soldier, and instead of seizing him, he brought him a horse, and entreated him to save himself by flight; then, having fallen at the king's feet with tears and begged his forgiveness, he hastened back to his employer, and told him that the story of Richard's arrival was false, and that the pilgrim was of no higher rank than a knight, and was named Baldwin of Bethune. The baron, furious with rage at his disappointment, ordered the arrest of Baldwin, who was cast into prison with several of his companions.

Meanwhile, Cœur-de-Lion hastened on his way through Germany, attended only by a single knight, and by a boy who spoke the English language, then very similar to the Saxon dialect of the Continent. For three days and nights they travelled without food among mountains covered with snow, not knowing in which direction they were going. They entered the province which had formed the eastern boundary of the old empire of the Franks, and was called Ostrik or Œstreich, which means the East Country. This country, known to us by the name of Austria, was subject to the Emperor of Germany, and was governed by a duke, whose capital was Vienna, on the Danube. This duke was the same Leopold whom Richard had insulted at Ascalon, and with whom also, on a former occasion, he had a serious quarrel. This occurrence took place at Acre, where the duke having presumed to raise his standard on a portion of the walls, Cœur-de-Lion seized the flag, and trampled it under foot.

Richard and his companions arrived at a small town near Vienna, exhausted with fatigue and fasting. It is not probable that the king could have proceeded so near the city without knowing where he was, but his immediate necessities were too pressing to leave any room for hesitation. Having taken a lodging, he sent the boy into the market-place to buy provisions; but here the same imprudence which had led to the former discovery was again exhibited. The boy was dressed in costly clothes, and these, together with the large sums of money which he exhibited, excited the suspicions of the citizens; but he made excuse that he was the servant of a rich merchant who was to arrive within three days at Vienna. When he returned to the king, he related what had happened, and begged him to escape while there was yet time. Richard, however, little accustomed to anticipate danger, and fatigued with his journey, determined to remain some days longer.

Meanwhile, Duke Leopold heard the rumour of the landing of his enemy at Zara, and, incited at once by feelings of revenge and by the hope of the large ransom which such a prisoner would command, sent out spies and armed men in all directions to search for him. As the duke was scarcely likely to anticipate the presence of the fugitive so near the capital, the search was made without success, and Cœur-de-Lion would doubtless have escaped undiscovered, if another strange act of carelessness had not drawn suspicion upon him. One day, when the same boy who had before been arrested was again in the market-place, he was observed to carry in his girdle some embroidered gloves, such as were only worn by princes and great nobles on occasions of ceremony. He was again seized, and the torture was employed to bring him to confession. He revealed the truth, and pointed out the house in which King Richard was lodging. Cœur-de-Lion was in a deep sleep when the room in which he lay was entered by Austrian soldiers. He immediately sprang up, and seizing his sword, which lay beside him, he kept them at bay, vowing that he would surrender to none but their chief. The soldiers, superior as their numbers were, hesitated to undertake the task of disarming him, and the Duke of Austria having been sent for, Cœur-de-Lion gave up the sword into his hands. Leopold received it with a bitter smile of triumph, and said, "You are fortunate in not having fallen prisoner to the friends of the Marquis Conrad; for had you done so, you were bat a dead man, if you had a thousand lives." The duke then caused him to be imprisoned in the castle of Turnsteign, where soldiers were appointed to guard the caged lion day and night with drawn swords.

No sooner did the Emperor Henry VI, of Germany learn the news of the arrest of Cœur-de-Lion, than he sent to the Duke of Austria, his vassal, commanding him to give up his prisoner. "A duke," said he, "has no right to imprison a king; that is the privilege only of an emperor." This strange proposition does not seem to have been denied by Leopold, who resigned the custody of the English king, on condition of receiving a portion of his ransom. The agreement having been concluded, Richard was removed from Vienna at Easter, A.D. 1193, and was confined in one of the imperial castles at Worms.

The two German princes, of whom it is difficult to say which appears to us in the most despicable light, entertained an equal hatred for their noble prisoner. How high the brilliant valour and abilities of Richard had placed him above his contemporaries, is evident from the jealousy with which they all regarded him; but the chief cause of the enmity of the emperor was the alliance which had been formed between Cœur-de-Lion and Tancred of Sicily. It will be remembered that at the time when the army of the Crusaders visited Sicily, Henry was preparing for a descent upon that kingdom, for the purpose of enforcing those claims to the throne which he held in right of his wife Constance, the heiress of William the Good. Soon after the departure of Richard from Messina (A.D. 1191), Henry appeared with a vast army before the walls of Naples, which city made a gallant defence against the invader. The emperor, although the immediate descendant of the great Frederic Barbarossa, was as deficient in military skill as in other manly qualities, and he saw his troops fall thickly around him, cut off by the fevers of that unaccustomed climate, without venturing to make a combined attack upon the city. At length he fell ill himself, and then he immediately raised the siege, and retreated. At the time when Cœur-de-Lion fell into his power, he was preparing for a second expedition to Italy, and the captivity of the English king afforded him greatly increased chances of success; for Richard was accustomed to adhere to his engagements, and it is probable that, had he been in possession of his Kingdom, he would have interfered to prevent the destruction of his ally. It appears that after that shameful bargain by which the person of the royal prisoner was transferred to the custody of the emperor, the place of his confinement was kept carefully concealed, and was for many months a matter of speculation not only in England, but in Germany. Before we follow further the fortunes of this adventurous king, it is necessary to go back to the period of his departure for the Holy Land, and to trace the course of events in England during his absence.

Longchamp and Hugh Pudsey.

The popular feeling which had been excited against the Jews at the time of Richard's coronation, and which he had done so little to repress, found vent in persecutions and massacres throughout the country. In those turbulent times there were among the people a certain number of lawless characters, who, ever eager for plunder, were doubly so when they could obtain it by means which were encouraged by their superiors, and permitted secretly, if not openly, by the clergy. To kill a Jew was regarded not only as no crime, but as a deed acceptable to God; and in England, as in Palestine, the pure and holy religion of peace was believed to give its sanction to acts of merciless bloodshed and plunder in February, A.D. 1190, a number of Jews were butchered in the streets of Lynn, in Norfolk, and immediately afterwards, as though by a preconcerted movement, similar bloody scenes were enacted at Norwich, Lincoln, St. Edmondsbury, Stamford, and York.

The massacre of York, which took place in March, a.d. 1190, was remark.able no less for the number of victims who were sacrificed than for the circumstances of horror which attended it. At nightfall, on the 16th of the month, a company of strangers, armed to the teeth, entered the city, and attacked the house of a rich Jew who had been killed in London at the coronation. His widow and children, however, still remained, and these the ruffians put to the sword, carrying off whatever property the house contained. On the following day the rest of the Jews in York, anticipating the fate which awaited them, appeared before the governor, and entreated permission to seek safety for themselves and their families within the walls of the castle. The request was granted, and the people of the persecuted race, to the number of not less than 1,000 men, women, and children, were received into the fortress, within whose strong walls they might hope to find shelter from their enemies. But for some reason or other the governor passed outside the gates, and returned attended by a great number of the populace. The Jews, whose misfortunes had made them suspicious, feared that they had been permitted to enter the castle only as into a slaughter-house, and refused to admit the governor, excusing their disobedience by their dread of the mob, who, it was evident, would enter with him if the drawbridge were lowered. The governor refused to listen to such an argument, reasonable as it was; and, whatever may have been his original intention, he now gave orders to the rabble to attack the rebellious Israelites. The command was willingly obeyed, and the populace, whose numbers were continually increased by all the vagabonds and ruffians of the neighbourhood, laid siege to the castle, and made preparations for taking it by assault.

It is related that the governor became alarmed at the tumult he had raised, and that he recalled his order, and eudeavoured to calm the excitement of the people; if so, his efforts were unsuccessful. Few things are easier than to rouse the passions of men—nothing more difficult than to quell them. The unhappy Jews heard the loud shouts of vengeance without the walls, and, foreseeing that they could make little or no defence against the force brought against them, slew first their wives and children, and afterwards, with a few exceptions, themselves.

Longchamp, Bishop of Ely, the chancellor of the kingdom, expressed his indignation at the war of extermination which seemed to be commenced against the Jews. He proceeded to York with a body of troops, displaced the governor from his office, and kid a heavy fine upon the rich men of the city. It does not appear, however, that the punishment was in any degree proportioned to the crime, or that it fell upon the actual perpetrators. The men upon whom the fine was levied were probably innocent of the outrage; but Longchamp was in want of money to transmit to his royal m.aster in Normandy, and he, no doubt, was glad of the pretext thus afforded him for obtaining it.

It has been already related that, before the departure of Richard for the Holy Land, ho had sold the chief justiciarship of the kingdom to Hugh Pudsey, Bishop of Durham, whose authority he afterwards curtailed by appointing other justiciaries, among whom was William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely. Longchamp, who also held the chancellorship, and the custody of the Tower of London, was the favourite of Richard, and he soon secured into his own hands the entire government of the country. The king, who had the greatest confidence in his loyalty and ability, issued letters patent, directing the people to obey him as their sovereign; and, by the authority of the Pope, the chancellor was also appointed legate of England and Ireland. Thus doubly armed with spiritual and temporal power, the rule of Longchamp was absolute throughout the kingdom.

Pudsey, however, had paid for the justiciarship, and was by no means disposed to see bis privileges swept away without making an effort at resistance. He accordingly laid his complaint before the king, and Richard, in reply, sent him letters, authorising him to share with Longchamp the authority which was his due. Armed with these, Pudsey made his appearance in London with great ceremony, but the barons of the kingdom assembled there refused to permit him to take his seat among them. After having in vain insisted upon the king's authority which he carried with him, the discomfited bishop proceeded in search of the chancellor, who was still with his troops in the north. When the two prelates met, Longchamp approached his brother of Durham with a smiling countenance and courteous demeanour, expressed himself ready to obey the commands of the king, and invited Pudsey to an entertainment on that day se'nnight in the castle of Tickhill. The Bishop of Durham, who possessed either more good faith or less shrewdness than is usual with statesmen in that or any other age, accepted the invitation; and as soon as he had passed the gates of the castle, Longchamp placed his band upon his shoulder and arrested him, saying that, as sure as the king lived, the bishop should not leave that place until he had surrendered, not only his claim to power, but all the castles in his possession. "This," said he, "is not bishop arresting bishop, but chancellor arresting chancellor." Pudsey was accordingly imprisoned, and was not released until he had fulfilled the requested conditions.

The power of Longchamp was now employed to the utmost to raise money for the king's necessities, and to further his own schemes of aggrandisement. Among the chroniclers are several who speak in strong terms of his avarice and tyranny, while there is only one[1] whose description of him is favourable. That one, however, was an impartial witness, and an authority whose words carry considerable weight. We are told that such was the rapacity of the chancellor that not a knight could keep his baldric, not a woman her bracelet, not a noble his ring, not a Jew his hoards of gold or merchandise,[2] He used his power to enrich his relations and friends, placing them in the highest and most profitable posts under government, and entrusting to them the custody of towns and castles, which he took from those who had previously held them. He passed through the country with all the pomp and parade of royalty, attended by more than a thousand horsemen; and it is related that whenever he stopped to lodge for the night, a three years' income was not enough to defray the expenses of his train for a single day. His taste for luxury was further ministered to by minstrels and jugglers, whom he invited from France, and who sang their strains of flattery in the public places, proclaiming that the chancellor bad not his like in the world.

There is an evident air of exaggeration about these statements, and many of them were to be referred to men as disaffected towards the king as towards his chancellor. If Longchamp reduced the country to poverty by his exactions, it is most likely that he was impelled to obtain the money by the demands of Richard: we shall presently see, however, that the national wealth was by no means exhausted by the burdens—heavy as they were—which it sustained. The loyalty of Longchamp has never been doubted, and there is no reason to believe that his government was generally tyrannous or unjust.

The nobles viewed the increasing power of the chancellor with feelings of envy; and Earl John, the brother of Richard, who had long entertained designs upon the throne, perceived that his chances of success were small indeed so long as a man devoted, to the king retained the supreme power in the realm. Some of the turbulent barons, to whom Longchamp had given cause of offence, attached themselves to John, and encouraged him in his ambitious schemes. While Richard was in Sicily he received letters from his brother containing various accusations against the chancellor of tyranny and misgovernment. It appears that these letters produced their effect, and that the king sent a reply directing that, if the accusations were proved to be true, Walter, Archbishop of Rouen, with Geoffrey Fitz-Peter and William Mareschal, should be appointed to the chief justiciarships, and that in any case they should be associated with Longchamp in the direction of affairs. Richard, however, was well aware of the treacherous disposition of his brother, and reflection satisfied him that the chancellor was more worthy of confidence than those who accused him. Before the departure of the fleet from Messina, the king sent letters to his subjects confirming the authority of Longchamp, and directing that implicit obedience should be rendered to him.

When John learnt that his brother was on his way to Acre, he took active measures for bringing his schemes into operation. Various disputes took place between him and the chancellor, and before long an occurrence took place which led to an open rupture between them. Gerald of Camville, a Norman baron, and one of the adherents of John, held the custody of Lincoln Castle, which be had purchased from the king. Longchamp—who, it is said, desired to give this office to one of his friends—summoned Camville to surrender the keys of the castle; but the baron refused compliance, saying that he was Earl John's liege-man, and that he would not relinquish his possessions, except at the command of his lord. Longchamp then appeared before Lincoln with an army, and drove out Camville, who appealed to John for justice. The prince, who desired nothing better than such an opportunity, attacked the royal fortresses of Nottingham and Tickhill, carried them with little or no opposition, and, planting his standard on the walls, sent a messenger to Longchamp to the effect that, unless immediate restitution were made for the injury to Gerald of Camville, he would revenge it with a rod of iron. The chancellor, who possessed little courage or military talent, entered into a negotiation, by the terms of which the castles of Nottingham and Tickhill remained in the hands of John, and that of Lincoln was restored to Camville. Other of the royal castles, which had hitherto remained exclusively in the power of the chancellor, were committed into the custody of different barons, to be retained until the return of Richard from the Holy Land, or, in the event of his death, to be delivered up to John. It was well known that the king had appointed his young nephew Arthur as his heir, but the chancellor was now forced to set aside the commands of his royal master, and at a council of the kingdom, the barons, headed by Longchamp, took the oath of fealty to John, acknowledging him heir to the crown in case the king died without issue.

These important concessions satisfied John only for a short time, and an opportunity soon presented itself for pushing his demands still further. Geoffrey, the son of Henry II. by Fair Rosamond, bad been appointed to the archbishopric of York during bis father's lifetime, but his consecration had been delayed until the year 1191, whom the necessary permission was received from the court of Rome, and he was consecrated by the Archbishop of Tours. As soon as the ceremony was concluded, he prepared to take possession of his benefice, notwithstanding the oath which had been exacted from him that he would not return to England. The chancellor having been apprised of his intention, sent a message to him forbidding him to cross the Channel, and at the same time directed the sheriffs to arrest him should he attempt to land. Geoffrey despised the prohibition; and, having landed at Dover in disguise, took shelter in a monastery. His retreat was soon discovered, and the soldiers of the king broke into the church and seized the archbishop at the foot of the altar, while he was engaged in the celebration of the mass. A good deal of unnecessary violence seems to have been used, and Geoffrey was dragged through the streets to Dover Castle, where he was imprisoned.

The peculiar circumstances of this arrest, and the indignity thus inflicted upon a prelate of the Church, excited the popular feeling strongly against the government, and John, satisfied that he would be supported by the people, openly espoused the cause of bis half-brother, and peremptorily ordered the chancellor to release him. Longchamp dared not resist the popular voice; he asserted that he had given no orders for the violence which had been used, and directed that the archbishop should be set at liberty, and suffered to go to London. An alliance, whose basis seems to have been self-interest rather than mutual esteem, was formed between the two half-brothers, and John, supported by the Archbishop of Rouen, boldly proceeded to London, summoned the great council of the barons of the kingdom, and called upon the chancellor to appear before it and defend his conduct. Longchamp not only refused to do so, but forbade the barons to assemble, declaring that the object of John was to usurp the crown. The council, however, was held at London Bridge, on the Thames, and the barons summoned Longchamp, who was then at Windsor Castle, to appear before them. The chancellor, on the contrary, collected all the men-at-arms who were with him, and marched from Windsor to London; but the adherents of John, who met him at the gates, attacked and defeated his escort; and finding himself also opposed by the citizens, he was compelled to take refuge in the Tower.

Immediately afterwards John entered the city, and, on his promising to remain faithful to the king, was received with welcome. The people, though they were willing to join in deposing the chancellor, retained, almost without exception, the utmost loyalty to their brave sovereign, and they showed clearly that they would permit of no treason against his authority. The act contemplated by the barons involved very important consequences, and John, with the craft and caution peculiar to his character, determined to obtain the assent of the citizens of London, and thus to involve them in a portion of its responsibility. The suffrages of the people were taken in a manner which shows at once the rudeness of the times, and the unusual nature of such a proceeding. On the day fixed for the great assembly of the barons, the tocsin, or alarm bell, was rung, and when the citizens poured forth from their houses, they found heralds posted in the streets, who directed them to St. Paul's Church. When the people arrived there in a crowd, they found the chief men of the realm—barons and prelates—seated in council. These haughty nobles, chiefly of Norman descent, whose usual custom had been to treat the native English as mere serfs and inferior beings, now received the people with extraordinary courtesy, and invited them to take part in the proceedings. The debate which followed, being conducted in Norman -French, must have been unintelligible to the majority of the citizens; but they were shown the king's seal affixed to a letter, which was said to authorise the deposition of the chancellor in case he failed to conduct properly the duties of his office. When this letter had been read, the votes of the whole assembly were taken, and it was decreed by the voice of "the bishops, earls, and barons of the kingdom, and of the citizens of London," that the chancellor should be deprived of his office, and that John, the brother of the king, should be proclaimed "chief governor of the whole kingdom."

Ricahrd Cœur-de-Lion before the Diet of the German Empire. (See page 237.)

On the news of these transactions being conveyed to Longchamp, it is reported that he fell upon the floor insensible. It was evident that he had no longer any power to resist the pretensions of John: resistance, to have been of any avail, should have come sooner. The troops of his opponents having surrounded the Tower, the chancellor came out from the gates and offered to surrender. John,who thought it worth while to buy his adhesion or submission to the new authority, proposed to leave him in possession of the bishopric of Ely, and to give him the custody of three castles belonging to the crown. To the honour of Longchamp, he refused to accept gifts from such a source, or to resign of his own free will any of the powers entrusted to him by his sovereign. "I submit," he said, "only to the superior force which is brought against me." And with these words he gave the keys of the Tower into the hands of John. The barons, however, compelled him to take an oath that he would surrender the keys of the other royal fortresses, and his two brothers were detained as hostages for the performance of these conditions.

The chancellor himself was permitted to go at large; and it appears that he determined, rather than resign possession of the castles, to leave his brothers in danger, and to escape to Normandy.

John kneeling for forgiveness before his brother Richard. (See page 239.)

Having reached Canterbury, he stayed there for a few the disguise of a hawking-woman, having a bale of linen under his arm, and a yard-measure in his hand. In this strange costume, the ex-chancellor, who had been accustomed to travel with a retinue of 1,000 men-at-arms, took his way on foot to the sea-shore. Having to wait awhile for a vessel in which to embark, he sat down upon a stone, with his veil, or hood, drawn over his face. Some fishermen's wives who were passing by stopped and asked him the price of his cloth, but as he did not understand a word of English, he made no answer, much to the surprise of his questioners. Presently some other women came up to him, who also took an interest in his merchandise, and desired to know how he sold it. The prelate, who seems to have been keenly alive to the ludicrousness of his situation, burst out into a loud laugh, which stimulated the curiosity of the women, and they suddenly lifted his veil. Seeing under it "the dark and newly-shaven face of a man,"[3] they ran away in surprise and alarm, and soon brought back with them a number of men and women, who amused themselves by pulling the clothes of this strange person, and rolling him in the shingles. At length, after the ex-chancellor had tried in vain to make them understand who he was, they shut him up in a cellar, and he was compelled to make himself known to the authorities as the only way of regaining his liberty. He then gave up the keys of the royal castles, and was permitted to proceed to the Continent.

Immediately on his arrival in Normandy, Longchamp wrote those letters to Richard which reached him in the Holy Land, and apprised him of the unsettled condition of affairs in England, and of the dangerous assumption of power on the part of John. That prince had appointed the Archbishop of Rouen to the chief justiciarship of the kingdom; but it would appear that the new justiciary was too honest a man to assent to all the views of his unprincipled maste; and John being in want of money, entered into a negotiation with Longchamp to replace him in his office for a payment of £700. The chief ministers, however, dreaded the consequences which might follow the return of the ex-chancellor to power; and they agreed to lend John a sum of £500 from the treasury, to induce him to withdraw his proposal. The mercenary prince consented to do so, and the negotiation was broken off.

In defiance of the solemn oath which Philip had taken before leaving the Holy Land, he no sooner returned to France than he prepared to invade Normandy. Some of the nobles of his kingdom, however, had more regard for their knightly faith, and they refused to join in the expedition; while the Pope, determined to defend the cause of a king who was so nobly fighting the battle of the faith, threatened Philip with the ban of the Church if he persisted in his treasonous intention. Compelled to abandon this expedition, the French king by no means gave up his designs against Richard, and he entered into a treaty with John, by which he promised to secure to him the possession of Normandy, Aquitaine, and Anjou, and to assist him in his attempts upon the English throne. In return he merely asked that John should marry the Princess Alice, Philip's sister.

To this match John, who probably might have been willing to promise anything that was required of him, did not hesitate to give his consent, in spite of the sinister rumours which were current about the princess, and the fact that she had been affianced to his brother.