Cassell's Illustrated History of England/Volume 3/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III.

REIGN OF CHARLES I.

Within a quarter of an hour after the decease of James, Charles was proclaimed by the knight-marshal, Sir Edward Zouch, at the court-gate at Theobalds. He was in his twenty-fifth year, and so far as the admission of his title, the substantial prosperity of the kingdom, and the relations to foreign states, was an earnest, few monarchs have mounted the throne with more favourable auspices. True, the territories of his brother-in-law, the palsgrave, were in the enemy's hands, his sister was a queen without a realm, an electress without an electorate; but even the condition of these affairs were not such as defied the efforts of a wise king, who had the protestant states of Germany and Holland in his favour, and was on the point of an intimate alliance with France. It was equally true that Charles had made an enemy of Spain, but the rupture there was not of a kind which defied the application of a wise and conciliatory policy. We shall be called upon, however, to observe how quickly and how irremediably the froward and headstrong spirit of Charles and his supercilious favourite, Buckingham, excited almost universal hostility towards him.

At home, though there was the most entire submission to his right to reign, and the state of parties was such that there demanded no immediate change of executive, yet there were at work feelings and principles which required the nicest wisdom to estimate their nature and their force, and the most able policy to deal with them. The battle betwixt prerogative and popular rights had to be fought out, and all depended on the capacity of the monarch to perceive what was capable of modulation, and what was immovable, whether the result should be success or ruin. Charles was equally prepared by his father's maxims, his father's practice, and his habit of favouritism, to convert one of the grandest opportunities in history into one of the most terrible of its catastrophes.

The first thing which augured ill for him was his continuing in the post of chief favourite and chief counsellor, the vain, incapable, and licentious Buckingham. It is very rarely that the favourite of a monarch continues that of his successor; but Buckingham had been made to feel that the old king's faith in him was shaken, and he had assiduously cultivated the good graces of the heir-apparent. His recommendation of the personal journey to Spain, was precisely the thing to captivate a chivalrous but not very profoundly percipient young man. In this journey Buckingham, with all his folly, sensuality, and audacity, had managed to seize a firm hold on the affectionate and tenacious nature of the prince; and his blind regard for him outlasted counsels of folly, and deeds of wickedness and weakness, which would have ruined him a score of tunes with a more sagacious patron.

The first matter to which Charles turned his attention was his marriage with the princess Henrietta Maria, sister of Louis XIII. of France, the contract for which was already signed. The third day after his accession, he ratified this treaty as king, which he had signed as prince. The pope Urban, as we have stated, seeing that he could not prevail on the royal family of France to give up the marriage with the heretic prince of England, at length had, through his nuncio, delivered the breve of dispensation.

Louis of France, the queen-mother, the bride, Gaston, duke of Orleans, and the duke of Chevreuse, Charles's proxy, signed the document with the English ambassadors, on the 8th of May, 1625, and the marriage took place on a platform in front of the ancient cathedral of Notre Dame on the 11th. That stately old fabric was hung with rich tapestry and tissues of gold and silver for the occasion. From the palace of the archbishop of Paris to the church, a gallery was erected on raised pillars draped with violet satin, and figured with golden fleurs-de-lis. A great procession marched from the Louvre to the archbishop's palace, and thence through this gallery to the church. First went Chevreuse, as representative of the king of England, arrayed in black velvet, and over it thrown a scarf glittering with roses composed of diamonds. The English ambassadors followed next, and after them walked the bride, wearing a splendid crown of England; her brother the king conducting her on the right hand, and her younger brother Gaston, the duke of Orleans, on the left. Her mother, Maria de Medici, followed her, and next to her Anne of Austria, the queen-consort, in a robe bordered with gold and precious stones, and her long train borne by princesses of the house of Conde and Conti. Marie Montpnsier, the great heiress afterwards married to Gaston, duke of Orleans, led the remaining ladies of the royal family.

At the church door, the king of France and his brother Gaston delivered the bride into the hand of Chevreuse, Charles's proxy, and the cardinal de la Rochefocault performed the ceremony. From the platform the bride and her attendants advanced into the cathedral, and witnessed mass at the high altar; but Chevreuse, acting exactly as a protestant for the protestant king, whom he represented, retired with the English ambassadors during these ceremonies to a withdrawing apartment prepared for the purpose. On the return of the royal procession to the Louvre, Henrietta, as queen of England, was placed at the banquet on the right hand of king Louis, and was served at dinner by the marshal Bassompierre. as her carver, and by marshal Vitry, the assassin of marshal d'Ancre, the grand panetier.

The duke of Buckingham arrived to conduct the young queen to England, attended by a numerous and splendid retinue of English nobility. The showy and extravagant upstart appeared at the French court in a style which threw even the monarch into the shade. He wore "a rich white satin uncut velvet suit, set all over, suit and cloak, with diamonds, the value whereof," say the Hardwicke Papers, "is thought to be worth fourscore thousand pounds; besides a feather made with great diamonds, with sword, girdle, hatband, and spurs with diamonds, and he had twenty-seven other suits, all rich as invention could frame or art fashion." His conduct was as devoid of all modesty as his address, and threw discredit on the king, his master, who intrusted his honour and his counsels to such a man.

The king, queen, and queen-mother, accompanied by the whole court, set out to conduct the young fiancée to the port where she should embark for England. The procession was made as gorgeous and imposing as possible, and at each halting place the court was amused by a variety of pageants and entertainments drawn from a past age. One alone of these deserves remark, being afterwards deemed ominous—a representation of all the French princesses who had become queens of England. They presented a group distinguished by their misfortunes, and the only one wanting to complete the number being herself yet a spectator, the girlish Henrietta, little more than fifteen years of age, who was destined to exceed them all in calamity.

The king was, however, seized with an illness, which compelled him to discontinue the journey, and at Compeigne the queen-mother was also taken so ill as to detain the procession a fortnight at Amiens. There the queen and queen-mother took leave of Henrietta, the mother putting into the young queen of England's hand at parting a remarkably eloquent and affectionate letter; which, however, was ill-advised, inasmuch as it clearly exhorted the young princess, who was going to live amongst a protestant people, to a bigoted adherence to all the mischievous notions of the truth only of popery, and of the dangerous heresy of her future subjects. But no doubt this was the spirit which had been carefully instilled into her mind from the first prospect of this alliance, and was not long in producing its bitter fruits. The plague being rife in Calais, the royal procession, now under the guidance of Buckingham, took its way to Boulogne.

Charles, during this delay at Amiens, had been awaiting his wife at Canterbury, and he was destined to a fresh one through the licentious madness of Buckingham. No sooner did that most impudent of libertines reach the French court than he had the audacity to fall in love with the queen of France, the beautiful Anne of Austria, sister of the king of Spain. He lost no opportunity of pressing his suit on the way in the absence of the king, and had the presumption to imagine his daring passion returned. No sooner did he reach Boulogne, than pretending that he had received some despatches of importance, he hurried back to Amiens, where the French procession yet remained, and rushing into the bed-chamber of the queen, threw himself on his knees before her, and, regardless of the presence of two maids of honour, poured out the infamous protestations of his polluted passion. The queen repulsed him with an air of deep anger, and bade him begone in a tone of cutting severity, the reality of which, however, was doubted by Madame de Motteville, who recorded the occurrence.

The sensation excited by this unparalleled circumstance in the French court was intense. The king ordered the arrest of an number of the queen's attendants, and dismissed several of them. Yet Buckingham, on reaching England, does not appear to have received any serious censure from his infatuated master, for this breach of all ambassadorial decency and etiquette; and spite of the resentment of the French king and court, continued to maintain all the character of a devoted lover of the French queen.

On the 23rd of June the report of ordnance wafted over from Boulogne, announced the embarkation; and on Sunday evening she landed at Dover, after a very stormy passage. Mr. Tyrrwhit, a gentleman of the household, rode post haste to Canterbury to inform Charles, who was at Dover Castle by ten o'clock the next morning to greet his bride. Henrietta Maria was at breakfast when the king was announced, and instantly rose, and hastened down stairs to meet him. On seeing him, she attempted to kneel and kiss his hand, but he prevented her, by folding her in his arms and kissing her. She had studied a little set speech to address him with, but could only get out so much of it as, "Sire, je suis venue en ce pays de voire majesté, pour étre commandée de vous"—"Sire, I am come into your majesty's country to be at your command"—but at that point she burst into tears.

It would have been well for her had she always retained the sentiment of those words, but at present she was all amiability. The king, who had not seen her since his stolen view on his way to Spain, was surprised to find her so tall as to reach his shoulder, and looked down at her feet to ascertain whether there was no artificial elevation; on which she gaily put out her foot, saying, in French, "Sire, I stand upon my own feet. I have no help from art. Thus high am I, neither higher nor lower." She then presented to his majesty the duke and duchess of Chevreuse, the prince Charles's relative and proxy, the latter the most celebrated beauty and coquette of the French court; Madame St. George, the queen's governess and favourite, and the rest of her followers, who amounted only to about four hundred! Amongst these were no less than twenty-nine priests of one kind or another, and a rather juvenile bishop, being not thirty years of age.

Charles was delighted with the beauty and vivacity of the young queen. They set out for Canterbury, and on their way thither were met on Barham Downs by the English nobility; pavilions being pitched there for the purpose of the refreshment of the royal pair, and the introduction of the queen to her court. After the wedding, at which the celebrated English composer, Orlando Gibbons, performed on the organ, the royal cavalcade took its way to Gravesend, and thence ascended the Thames, so as to avoid the city, in which the plague was then raging. Thousands of boats of all kinds floated around the royal barge, and the fleet of fifty vessels lying ready for the Spanish expedition, discharged their ordnance as well as the Tower its guns. And thus, in the midst of a smart shower, they reached London Bridge, and made straight for Somerset House, which was the queen's dower palace. The assembled crowds all the way gave shouts of acclamation, and, spite of the queen's popery, every so was in a mood to be pleased with her. She shook her hand out of the barge window in return for the public greeting, and many anecdotes were circulated in her favour; as that on the vigil of St. John the Baptist, she had eaten both pheasant and venison at Canterbury, though her confessor had stood by her and reminded her that it was a fast; and that, when one of the English suite had asked her if her majesty could endure a Huguenot, she had answered, "Why not? was not my father one?"

But it was not long before she let her new subjects as well as the king see that she was of a wilful and haughty temper. The first time that she kept court at Whitehall, a Mr. Mordaunt, who was present, wrote the following: "The queen, however little in stature, is of a most charming countenance when pleased, but full of spirit, and seems to be of more than ordinary resolution. With one frown—divers of us being at Whitehall to see her—she drove us all out of the chamber, the room being somewhat over-heated with fire and company. I suppose none but a queen could have cast such a scowl."

But we must interrupt the domestic life of the king to notice the commencement of his public career. On the 18th of June, the day after the arrival of the queen, Charles met his first parliament. The king had not yet been crowned, but he appeared on the throne with his crown on his head. He ordered one of the bishops to read prayers before proceeding to business, and this was done so adroitly, that the catholic members were compelled to remain during the heretical service. They betrayed great uneasiness, some kneeling, some standing upright, and one unhappy individual continuing to cross himself the whole time.

Charles was not an eloquent speaker, and he, moreover, was afflicted with stammering; but he plunged boldly into a statement which it was very easy for the two houses to understand. He informed them that his father had left debts to the amount of seven hundred thousand pounds; that the money voted for the war against Spain and Austria was expended, and he therefore called upon them for liberal supplies. He declared his resolution to prosecute the wars which they had so loudly called for with vigour, but it was for them to furnish the means.

As he was beginning his reign, and had not plunged himself into very heavy debt, or preached up, like his father, the claims of the prerogative, he had a right to expect a more generous treatment than James. But, notwithstanding the éclat of a new reign, and the usual desire on such occasions to stand well with the throne, the commons displayed no enthusiasm in voting their money. There were many causes, even under a new king, to produce this coolness. Charles had won their popularity by abandoning the Spanish match, but he had now neutralised that merit by taking a catholic queen from France. To please the commons and the public generally, he should have selected a wife from one of the protestant houses of Germany or the Netherlands; but for this he had displayed no desire. In the second place, he had retained the hated Buckingham in all his former eminence, both as a minister of the crown, and as his own associate. The recent conduct of this profligate man in France had outgone his folly and vice in Spain, and had outraged all the most serious feelings and sacred sentiments of the nation. Besides, they had no faith in his abilities, either as a commander or a statesman, and beheld with disgust his reckless extravagance and unconcealed infamy of life at home. No talent whatever had been shown in the war in Germany for the restoration of the Palatinate; and, therefore, the commons, instead of voting money to defray the late king's debts, and to carry on the war efficiently, restricted their advances to two subsidies, amounting to about one hundred and forty thousand pounds, and to the grant of tonnage and poundage, not for life as afore-time, but merely for the year.

But still more apprehensive were they on the subject of religion. The breach with Spain had naturally removed any delicacy on the part of the Spaniards to conceal the treacherous concessions, in perfect contradiction to the public professions of both the late and the present king, which had been made on that head. It was now freely whispered that the like had been made to France, and the sight of the crowd of priests and papistical courtiers who had flocked over with the queen, and the performance of the mass in the king's own house, led the zealous reformers to believe that there was a tacit intention on the part of the king to restore the catholic religion.

What rendered the commons more sensitive on this head were the writings of Dr. Montague, one of the king's chaplains, and editor of his father's works. In a controversy with a catholic missionary, he had disowned the Calvinistic doctrines of the puritans with which his church was charged, and declared for the Arminian tenets of which Laud was the great champion. This gave great offence; he was accused of being a concealed papist, and two puritan ministers. Yates and Ward, prepared a charge against him, and laid it before parliament. Montague denied that he was amenable to parliament, and "appealed unto Cæsar." Charles informed the commons that the cognisance of his chaplains belonged to him, and not to them. But they asserted their right to deal with all such cases, and summoned him to appear at the bar of the house, where they bound him in a bond of two thousand pounds to appear when called for.

Charles endeavoured to recall their attention to the state of the finances, showing them the inadequacy of their votes; the fitting out of the navy amounting alone to three hundred thousand pounds. He was beyond all indignant at the grant of tonnage and poundage for only one year, seeing that his predecessors from the time of Henry VI., had enjoyed it for life; and the lords threw out that part of the vote for this reason, so that he had no parliamentary right to collect that at all. To make matters worse, instead of listening to the pleading of lord Conway, the chief secretary, for further grants, they presented to the king, after listening to four sermons one day, and taking the sacrament the next, a "pious petition," praying him, as he valued the maintenance of true religion, and would discourage superstition and idolatry, to put in force all the penal statutes against catholics.

To this demand Charles could only return an evasive answer. He had recently bound himself by the most solemn oaths to do nothing of the kind; and under the sanction of the marriage treaty with France, the mass was every day celebrated under his own roof, and his palace and its immediate vicinity swarmed with catholics and their priests. Nay, he had, just before summoning parliament, been called on by France to send a fleet in virtue of this treaty to assist in putting down the Huguenots. Soubise, the general of the Huguenots, still retained possession of Rochelle and the island of Rhé, and their fleet scoured the coasts in such force, that the French fleet dared not attempt to cope with it. Richeileu, therefore, called on Charles to give Louis assistance. Accordingly, though the affairs of the English fleet had been most woefully conducted ever since Buckingham had been lord admiral, he mustered seven merchant vessels, and sent them with the Vanguard, the only ship of the line that was fit for sea, under the command of admiral Pennington, to Rochelle. The destination of the fleet was declared to be Genoa, but on reaching Dieppe, the officers and crew were astonished to receive orders to take on board French soldiers and sailors, and proceed to Rochelle to fight against the protestants. They refused to a man, and notwithstanding the imperative commands of the duke of Montmorency, the lord admiral of France, they compelled their own admiral to put back to the Downs.

On this ignominious return, Pennington requested to be permitted to decline this service, and his desire was much favoured by the remonstrances of the Huguenots, who sent over an envoy, entreating the king not to give such a triumph to popery as to fight against the protestants. Charles, with that fatal duplicity which he had learned so early under his father, sent fair words to Soubise, the duke of Rohan, and the other leaders of the Huguenots; but Buckingham, by speaking out more plainly, exposed the hollowness of his master. He assured the navy that they were bound by treaty, and fight they must for the king of France. Both officers and owners of the ships declared that as they were chartered for the service of the king of England, they should not be handed over to the French without an order from the king himself. Thereupon Buckingham hastened down to Rochester, accompanied by the French ambassador, who offered to charter the vessels for his government. Men, owners, and officers, refused positively any such service.

Charles I.

Disappointed by this display of true English spirit, Charles ordered secretary Conway to write to vice-admiral Pennington in his name, commanding him that he should proceed to Dieppe and take on board as many men as the French government desired, for which this letter was his warrant. At the same time Pennington received an autographic letter from Charles, commanding him to make over the Vanguard to the French admiral at Dieppe, and to order the commanders of the seven merchant ships to do the same, and in ease of refusal to compel them by force. All this appears to have been imposed on Pennington as a matter of strict secrecy; and that officer had not the virtue to refuse so degrading a service. The fleet again sailed to Dieppe: the men must have more than suspected the object; and when Pennington made over the Vanguard, and delivered the royal order to the captains of the several merchant vessels, to a man they refused to obey, and weighed anchor to return home. On this Pennington, who proved himself the fitting tool of such a king, fired into them, and overawed all of them except Sir Ferdinand Gore, in the Neptune, who kept on his way, disdaining to disgrace himself by such a deed.

The French were taken on board and conveyed to Rochelle. But that was all that was accomplished; for the English seamen instantly deserted on reaching land, and many of them hastened to join the ranks of the Huguenots, the rest returning home overflowing with indignation, and spreading everywhere the disgrace of the royal conduct.

In the whole of this transaction the headstrong fatality of

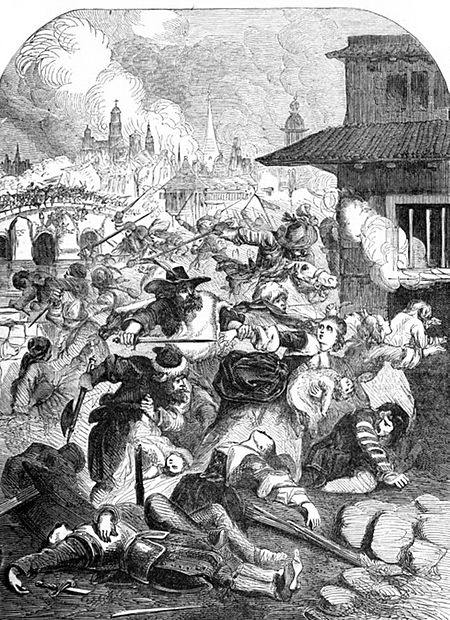

DEATH OF KING JAMES I.

Charles was conspicuous, and foreboded the miseries that were to follow. In the midst of the public excitement from this pause, the parliament met at Oxford on the 1st of August. The result was as might have been expected. On the king demanding the restoration of the vote of tonnage and poundage, negatived by the lords, or that other subsidies should be granted in lieu of this, the commons refused both. In reply to the king's inquiry how the war was to be carried on, they replied that they must first be satisfied against whom the war was ready to be directed. They complained that the penal statutes against the papists were not enforced as promised, and proceeded to their favourite avocation of attacking the public grievances. On this topic Coke came forward with an eloquence and a boldness which astonished the court. With unsparing vigour worthy of his earlier years—but in a much better cause than that in which his abilities were then often exercised—he denounced the new offices created, the monopolies granted, and the lavish waste of the public money, all for the benefit of Buckingham and his relations. He insisted that the useless pensions which had been recently granted should be stopped till the late king's debts were paid, and that a system of strict economy should be substituted for the now extravagant expenditure of the royal household. Others followed in the same strain, denouncing the odious practice of selling offices, in which Buckingham and his mother were the great vendors.

A third party showed that they were armed with dangerous matter by the still disgraced and restrained earl of Bristol. They charged Buckingham with his maladministration of affairs, with his incompetency as lord high admiral, and with having involved this country in an unnecessary war with Spain, merely in revenge of a private quarrel with the Spanish minister, Olivarez. They demanded an inquiry into that affair. One of the members of the house venturing to defend the government, and condemning the licence of speech against the crown, was speedily brought upon his knees, and compelled to implore pardon at the bar. Sir Robert Cotton, the founder of the Cottonian Library, applauded the wisdom and spirit of the house in thus summarily dealing with this unworthy member; and after giving a description of the conduct of the late favourite, Somerset, and of the follies and crimes of favourites of former reigns, as the Spencers, the Gavestons, the Poles, and others, pronounced Buckingham as far more insolent, mischievous, and incompetent than any of them.

The favourite, thus rudely handled, was quietly enjoying himself at Woodstock; but the king sent and made him aware of the necessity of defending himself. He hastened to town, and delivered in his place in the peers, a statement of the accounts of the navy, and a stout denial of any personal motives in the quarrel with Spain. He clearly showed that he felt whence the danger came, and alluding to the earl of Bristol, said, "I am minded to leave that business asleep, but if it should awake, it will prove a lion to devour him who co-operated with Olivarez."

To cut short these awkward debates, the king sent word to the commons that as the plague was already in Oxford, it was necessary to make quick work, and that they should furnish the grant of supplies. He offered to accept for the present forty thousand pounds; but the house refused even this, saying that if that was all that was necessary, it might readily be raised by a loan to the crown. This put the king beyond his patience, and he menaced them with a speedy dissolution; adding if they were not afraid of their health, he would take care of it for them, by releasing them from the plague-invaded city, and find some means of helping himself The commons were not in a temper to be intimidated; on the contrary, they went into a most warm and spirited debate on the king's message, and appointed a committee to prepare a reply. In this they thanked him for his care of their health, and of the religion of the nation, and promised supplies when the abuses of the government were redressed; and they called upon him not to suffer himself to be prejudiced against the greatest safeguard that a king could have—the faithful and dutiful commons—by interested persons. Before they had time, however, to present this address, Charles dissolved the parliament, which had only sat in this Oxford session twelve days.

Thus deprived of all the necessary funds for a war, none but so infatuated a monarch as Charles would have persisted in plunging into it. War had not yet been proclaimed against Spain; it was neither necessary nor expedient; on the contrary, every motive of political wisdom warned him to keep peace in that quarter, if he really wished to be at liberty to prosecute the interests of the palsgrave and the protestant cause. But led by the splenetic imbecility of Buckingham, so far was he from seeing the folly of a war with Spain, that he was soon pushed into one with France. In fact, he took every step which would have been avoided by a wise prince, and speedily involved himself in a labyrinth of difficulties inextricable. Spain quieted and even soothed; France cultivated, with the object of obtaining its influence and aid in the recovery of the Palatinate; and the protestants of Germany sympathised with, if not aided substantially in their severe struggle against Austrian bigotry, Charles might have eventually restored his sister and her husband to their old estate, and have won a place in the European world superior to any king of his time. Instead of this, he took the surest means to exasperate his own people, and his most powerful neighbour, that his worst enemies could have suggested.

To raise money for the prosecution of the war against Spain, he ordered the duties of tonnage and poundage to be levied, notwithstanding they were not voted by the peers. He issued writs of privy seal to the nobility, gentry, and clergy, for loans of money, and menaced vengeance if they were not complied with. All salaries and fees were suspended, and to such a strait was he reduced by his efforts to man and supply the fleet, that he was obliged to borrow three thousand pounds from the corporations of Southampton and Salisbury to enable him to meet the expenses of his own table.

At length the fleet was ready to sail with a force of ten thousand men; the English fleet consisting of eighty sail, and the Dutch sent an addition of sixteen sail. In weight and armament of ships such a force had scarcely ever before left an English port. But formidable as was this naval power, it was rendered perfectly inert by the same utter want of judgment and genius which marked all the measures of Buckingham. Its destination was to have been kept secret, so that it might take the Spaniards by surprise; but it was well known, not only to that nation, but to the whole Continent. In spite of this, such a force in the hands of a Drake or a Nottingham, might have struck a ruinous blow to the Spanish navy and seaports; but Buckingham, for his own selfish purposes, appointed to the command Sir Edward Cecil, now created viscount Wimbledon, a man who had, indeed, grown grey in the service of the states of Holland, but only to make himself known as most incompetent to such an enterprise. He was, moreover, a land officer, whilst the admiral to whom the command regularly fell, in case the lord high admiral himself did not take it. Sir Robert Mansell, vice-admiral of England, had a high reputation, and the confidence of the men as an experienced officer.

On the 3rd of October this noble but ill-used fleet sailed from Plymouth, and took its way across the Bay of Biscay, where it encountered one of its storms, and received considerable damage, one vessel foundering with a hundred and seventy men. The admiral had instructions to intercept the treasure ships from America, to scour the coasts of Spain, and destroy the shipping in its harbours. But instead of doing that first which must be done then if at all—attack the ships in the ports—he called a council, and was completely bewildered by the conflicting opinions given. The conclusion was to make for Cadiz, and seize its ships, but the Spaniards were already aware of and prepared for them. Instead of keeping, moreover, a sharp watch for the Plata ships, he, Wimbledon, let several of them escape into port, which of themselves were thought, says Howell, rich enough to have paid all the expenses of the expedition. There was still nothing to prevent a brave admiral attacking the vessels in harbour; but more accustomed to land service, the commander landed his forces, and took the fort of Puntal. Making next a rapid march towards the bridge of Suazzo, in order to cut off the communication between the Isle de Leon and the continent, his soldiers discovered some wine cellars by the way, and became intoxicated and incapable of preserving order. Alarmed at this circumstance, their incapable leader conducted them back to the ships. Not daring to attack the port, he determined to look out for the treasure ships. But whilst cruising for this purpose, a fever broke out on board the vessel of lord Delaware; and as if it were his intention to diffuse the contagion through the whole fleet, the admiral had the sick men distributed amongst the healthy ships. A dreadful mortality accordingly raged through the whole fleet. No Plata ships could be seen, for they appear to have been aware of their enemies, and held away towards the Barbary coast; and after waiting fruitlessly for eighteen days, Wimbledon made sail again for England. No sooner did this imbecile quit the coast than fifty richly laden vessels entered the port of Lisbon. On landing at Plymouth, with the loss of a thousand men, in this most ignominious voyage, the people received the admiral with hisses and execrations. Under Henry VII. or Elizabeth, the commander would have paid for his misconduct with his head; Charles did not even order a court-martial to investigate the causes of the disgraceful failure, but submitted it to inquiry before the privy council. There Wimbledon laid the blame on the ignorance and insubordination of the officers under him, and the earl of Essex and the rest accused him of utter incapacity. The wretched Wimbledon threw himself on the support of the favourite, who had selected him, and Buckingham, who seemed ready to dare any amount of odium, protected him; the matter being left to sink into silence as the resentment of the public subsided, or fresh causes of anger superseded it.

The failure of the enterprise, however, was extremely embarrassing in another respect. The magnificent promises of wealth from the capture of the rich argosies of the Spaniards hail all vanished into thin air, and money must be raised by some means. The favourite, therefore, set off into Holland with the crown jewels and the royal plate, which he pawned for three hundred thousand pounds. He then entered into a treaty with the king of Denmark, who engaged, on the payment of a monthly subsidy from England and another from the United Provinces, to furnish an army of thirty-six thousand men. Thence Buckingham contemplated a journey to Paris; but his conduct there on occasion of his last visit was not likely to be forgotten, and he received a message from Richelieu forbidding his reception. The principal courtiers even vowed that if he ever ventured there they would take his life.

This rebuff had the effect upon his vain and vindictive mind, which all such wounds to his pride had. He at once sought to avenge himself, and in his resentment he would ruin kingdoms if possible. Lord Holland, who was thoroughly in his interest, and Sir Dudley Carleton, were despatched there in his stead; but they did not go to strengthen the alliance, a matter of so much importance, but to insult and irritate the French court. They were instructed, not, as the true policy would have been, to unite their influence with that of England, for the restoration of the palsgrave, but to demand the restoration of the ships which had been lent to France, and to open a communication with Louis's revolted subjects, the Huguenots. If Louis proposed measures to draw closer the alliance, which of all things was desirable, they were to refer the matter home, but they were not to fail in cultivating a friendship with the insurgent protestants, and to assure them of assistance on any emergency. The whole was the policy of a mean and suicidal spite. Richelieu, however, manifested a much deeper statesmanship than Charles or Buckingham was capable of. He at once promised the restoration of the ships, defeated the designs of England by making peace with the Huguenots, and then, with an air of friendliness, volunteered to send an army into Germany if Charles would do the same. That subtle statesman seemed as if he would show them the paltry and egregious folly of their conduct.

Defeated in this quarter, Buckingham sought revenge in another. The queen's French attendants had caused the king much annoyance, and there can be little doubt that Buckingham seized the present occasion to get them sent without ceremony from the country. Charles was passionately attached to his young queen, who was handsome, lively, and, when in good humour, extremely fascinating; but she soon showed that she had a strong self-will and a petulant temper. In whatever did not please her, the horde of French men and women who surrounded her, found occasion to encourage her discontent, and stimulate her to opposition. Her favourite, Madame St. George, seems to have been especially active in this mischievous style; and Charles became excessively incensed against them. Particularly on the subject of the queen's chapel and the open display of her religion, the priests stirred up the queen to importune the king. These foolish bigots could not see that Charles was placed in a most awkward situation by the toleration of that religion at all. He had set apart one of the most retired chambers in Whitehall for her chapel, and had forbidden any English people, men or women, to attend the service there. But this did not satisfy the priests: they tugged the queen perpetually to demand from the king the chapel at St. James's, and to have it fitted up with all the embellishments and apparatus of a royal open chapel. Charles angrily replied that if the queen's closet was not large enough, they could have the great chamber; if that would not hold them, they might go into the garden; and if the garden were too contracted, then the park was the fittest place. One change he made, which was done with his usual want of tact. The name of Henriette, as the French called it, and its French pronunciation, was so unaccustomed to English ears, that she was prayed for in the royal chapel by the name of "queen Henry," and he, therefore, ordered her second name, Maria, to be anglicised into Mary, in the public service. This was most ominous and hateful to the ears of his subjects, who were thereby reminded that they had again a queen Mary, and papist queen too.

Charles found her confessor. Father Sancy, a most troublesome, impertinent fellow, who exercised the worst influence over the queen; and he insisted on his being at once sent home, but did not succeed without much trouble. Then Madame St. George took unease offence at the king's not following her to ride in the same coach with himself and the Queen, as though she had the right to do that irrespective of the king's will, because she had thus accompanied the princess in France as her governess. Spite of the king's command, she persisted in thrusting herself in, and he was obliged to prevent her forcibly. In her anger at this, she worked the queen into a most offensive humour. "From that hour" wrote Charles to Henrietta's mother, "no man can say that my wife has behaved two days together with the respect that I have deserved of her." To settle these matters, Charles sent to the queen by the count de Tilliers, one of the heads of her establishment, the regulations which had been kept in the court of the queen, his own mother, and desired the count to see that they were kept. To this Henrietta sent back the reply, "I hope I shall be allowed to order my own house as I think best."

Charles complained grievously, and most justly, to Mary de Medici, of this; observing that if she had spoken to him privately about it, he would have done all he could to please her, but he could not have imagined her offending him in that public manner. "After this answer," he continued, "I took my time, when I thought we had leisure to dispute it out by ourselves, to tell her both her fault in the publicity of such answers, and her mistakes in the business itself. She, instead of acknowledging her mistakes, gave me so in an answer that I omit to repeat it. When I have anything to say to her, I must manage her servants first, else I am sure to be denied. Likewise I have to complain of her neglect of the English tongue, and of the nation in general."

It was clear that the crew of insolent foreigners must be packed off before there could be any domestic peace; but this might have been long delayed had Buckingham been permitted to visit Paris. He wrote to the favourite whilst in the Netherlands his complaints on this head, telling him that he was tempted to send away the monsers (monsieurs), because it was told him that they were actually intending to steal away his wife, and were plotting amongst his own subjects. He says that he cannot find positive proof of their scheme for carrying off the queen to France on the plea of ill-usage; but as to the plotting, he has good grounds to believe it. In another letter to Buckingham, he says, "As for news, my wife begins to mend her manners. I know not how long it will continue: they say she does so by advice." Probably her mother, Mary de Medici, had given her that sensible advice; at all events, the catastrophe of the French exodus was delayed till Buckingham came home, fuming against the whole French court.

Meantime Charles, who was in straits with his parliament and subjects, which needed not the humour of a froward wife to aggravate them, was compelled to try again the more than dubious resort to parliament for money. All that Buckingham had raised on the plate and jewels, was but as a mite in the great gulf of his necessities. To prepare the way for any success with the commons, he was obliged to do that which must certainly embroil him with his French allies, and add fresh fuel to the fire of domestic discord which consumed him. Certainly never had any man a more difficult part to play, except such a man as had acted with such absolute want of prudence in his measures; for nothing is easier than for men, by their folly or absurd resentments, to knit themselves up into a web of difficulties. He now resolved to break his marriage oath to France, and persecute the catholics to conciliate the protestants.

Orders were accordingly issued to all magistrates to put the penal laws in force; and a commission was appointed to levy the fines on the recusants. All catholic priests and missionaries were warned to quit the kingdom immediately, and all parents and guardians to recall their children from catholic schools, and young men from catholic colleges on the Continent. But worse than all, because personally insulting and irritating to the higher classes, who constituted the house of peers, and who hitherto had exhibited much forbearance, he conceded to the advice of his council, that the catholic aristocracy should be disarmed. The effect of this order may be imagined, from a scene which took place at a seat of lord Vaux, in Northamptonshire. The deputy-lieutenant, accompanied by two knights, and a Mr. Knightly, a magistrate, proceeded to make a search. They found there lord Vaux, his mother, and a younger brother of lord Vaux. In conducting the search Mr. Vaux, the younger brother, became excited by the indignity of the process, and observed that he thought the inspectors had now done everything they could except cutting the throats of the recusants, and swearing that he wished it would come to that. Knightly told the young man that he was mistaken: there were various clauses of the statutes which they had not put in force; as for instance the tine of twenty pounds per month for non-attendance at church, as well as a fine of twelve pence for every oath, and forthwith demanded that penalty from him. Young Vaux refused with hot words and fresh oaths; Knightly then demanded that lord Vaux or his mother should pay it for him; and on their refusal ordered the constables to distrain to the amount of three shillings on the goods. This put the finish to the patience of lord Vaux himself, who told Knightly that he would call him to account for his conduct in another place; on which Knightly replied that his lordship knew where he lived. Lord Vaux, in his anger, thrust Knightly out of the house, saying that he had done, and should now go about his business; but this infuriating Knightly, he turned back again, declaring that he had not done, he would make a farther search. The parties thereupon came to blows: lord Vaux broke the head of Knightly's man with a cudgel, and the deputy-lieutenant and his followers thought it time to get away. Lord Vaux was soon after arrested by the privy council on the complaint of Knightly, and dealt with in the star-chamber.

Certainly no proceedings could indispose the house of peers to the king more than such as these; but meantime Charles was active in endeavouring by other measures to win a party there. The earl of Pembroke had for some time made himself head of the opposition, and on great occasions brought with him on a vote no less than ten proxies, Buckingham himself being only able to command thirteen. He prevailed on Pembroke to be reconciled to the favourite; and at the same time, to punish the lord-keeper Willams, who had quarrelled with Buckingham, and told him that he should go over to Pembroke, and labour for the redress of the grievances of the people, he dismissed him, and gave the great seal to Sir Thomas Coventry, the attorney-general.

To manage the commons, and to prevent the threatened impeachment of Buckingham, when the judges presented to him the lists of sheriffs, he struck out seven names, and wrote in their places seven of the most able and active of the leaders of opposition in the commons, the most determined enemies of the favourite, namely:—Sir Edward Coke, Sir Thomas Wentworth, Sir Francis Seymour, Sir Robert Philips, Sir Grey Palmer, Sir William Fleetwood, and Edward Alford. As this office disqualified them from sitting in parliament, the king thus got rid of them for that year; but Coke contended that though a sheriff could not sit for his own county, he could for another, and got himself elected for the county of Norfolk, but did not venture to take his seat.

All these measures, it will be seen, were dictated not by a desire to conciliate, but to override the parliament, and therefore could not promise much good to a mind of any depth of penetration. Parliament was summoned for the 6th of February, 1626, and the 2nd was appointed for the coronation. In this ceremony the king was destined to suffer a deep mortification. All previous queens had been most anxious to share in the coronation of their husband, and that grace had by several monarchs been refused, especially by Henry VII. But the unwise French papists about Henrietta persuaded her to decline a ceremony which must be performed by a heretic prelate; a fatal advice, for it gave rise in after years to the assertion of her enemies, that as she had never been crowned, she never was lawful queen-consort.

Charles did all in his power to conquer her prejudices and prevail on her to be crowned—no British queen having ever refused such an honour before; but neither conjugal affection, nor a desire to stand well with the great nation with which her lot was cost, nor those natural feelings in a young and handsome woman to shine as the first of her sex in the most magnificent ceremony of the realm, could shake her resolve. She would not even consent to be present in a latticed box at her husband's coronation, her absence having the effect of preventing the French ambassador being there; for though he declared he would have strained his conscience a little to have taken his proper place in the assembly, etiquette made that impossible, when the sister of his master, the queen of the nation, was not there even as a spectator.

The popularity of Henrietta received a death-blow from this perverse conduct: the people never forgave the slight upon their crown and country by this ill-advised and obstinate girl, and this feeling was heightened by attendant circumstances. The day was Candlemas Day, a high festival in the catholic church, which was celebrated with all its formalities by Henrietta, whilst her protestant husband was being crowned in Westminster Abbey. The people saw her standing at a window of Whitehall gate-house, King Street, watching the procession as it went and returned, and her French ladies dancing and capering about her in the room.

The ceremony of the coronation itself was destitute of any national joy. Charles had alarmed the religious feelings of the nation, and had already infected his subjects with want of faith in him. Laud, who was ill high favour with both Charles and Buckingham, was a conspicuous object on the occasion, and had made several alterations in the service, and composed a new prayer; all his changes tending to that exaltation of church and state for which he lived, and for which he lost his head. Buckingham was lord constable for the day, another circumstance calculated to find no favour with the people. In ascending the stops of the throne, instead of giving his right hand to the king, he gave him his left, which Charles put by with his right hand, and assisted the duke, saying, "I have as much need to help you as you to help me." Nor was this the only strange thing observed on the occasion. Archbishop Abbot, who performed the ceremony of anointing, was regarded by many as still not canonical, on account of his accidentally killing the king's keeper whilst hunting, although he had received absolution. He performed the act of anointing behind a screen raised for the purpose, so much was the puritans' disapprobation of this ceremony dreaded; and when the archbishop presented the king to the people as their rightful king, and called upon them to testify their consent by their general acclamation, there was a dead silence. Lord Arundel, the earl marshal, hastened to bid them shout, and cry "God save the king," but the response was but very faint and partial.

With the knowledge of a discontented people, Charles went to meet his parliament, and this consciousness would, in a monarch capable of taking a solemn warning, have operated to produce conciliation, at least of tone; but Charles was one of that class of men who suggested the striking words to the Latin fatalist that, He whom God intends to destroy he first drives mad. Accordingly, he opened the sitting with a curt speech, referring them to that of the new lord keeper Coventry, which was in the worst possible taste. He said, "If we consider aright, and think of the incomparable distance between the supreme height and majesty of a mighty monarch, and the submissive awe and lowliness of loyal subjects, we cannot but receive exceeding comfort and contentment in the frame and constitution of this highest court, wherein not only prelates, nobles, and grandees, but the commons of all degrees have their part; and wherein that high majesty doth descend to admit, or rather to invite, the humblest of his subjects to conference and council with him."

Of all language this was, in the temper of the commons, the most adapted to incense them. Such talk of the condescension of the crown, at the moment when they were entering on a desperate conflict with it for curbing the prerogative, only the more stimulated their resolution to their task. They immediately formed themselves into three committees; one of religion, a second of grievances, and a third of evils. They again, by the committee of religion, canvassed the subject of popery; resolving to enact still severer laws against it, as the origin of many of the worst evils that afflicted the nation. They summoned schoolmasters from various and remote parts of the kingdom, and put searching questions to them, as to the doctrines which they held and taught to their scholars; and every member of the house was called upon in turn to denounce all persons in authority or office, known to them as holding the tenets of the ancient faith. In fact, in their vehement zeal for religious liberty, the zealots of the house were on the highway to extinguish every spark of toleration, and to convert the house of commons into an inquisition, instead of the bulwark of popular right.

They again summoned Dr. Montague to redeem his bail, and receive punishment on account of his book, in which they charged him with having admitted that the church of Rome was the true church, and that the articles on which the two churches did not agree were of minor importance. Laud advocated the cause of Montague at court, for he was of precisely the same opinions, and urged the king and Buckingham to protect him. But both Charles and the favourite saw too many difficulties in their own way to care to interfere in defence of the chaplain. They left him to his fate, and he would have been, no doubt, severely dealt with, had not higher matters seized the attention of the house, and caused the offending churchman to become overlooked.

This was the impeachment of Buckingham. The committee of grievances had drawn up, after a tedious investigation, a list of sixteen grievances; consisting of such as had so often been warmly debated in the last reign; the most prominent of which they regarded the practice of purveyance, by which the officers of the household still collected provisions at a fixed price for sixty miles round the court; and the illegal conduct of the lord treasurer, who went on collecting tonnage and poundage, though unsanctioned by parliament. They charged the maintenance of these evil to the advice and influence of a "great delinquent" at court; who had, moreover, occasioned all the disgraces to the national flag, both by land and sea, which had for some years occurred, and who ought to be punished accordingly.

The time was now actually arriving of which James had warned his son and Buckingham, when they urged the impeachment of the earl of Middlesex, but choosing to forget all that, Charles sent down word to the house that he did not allow any of his servants to be called in question by them, especially such as were of eminence and near unto his person. He remarked that of old the desire of subjects had been to know what they should do with him whom the king delighted to honour, but their desire now appeared to be to do what they could against him whom the king honoured. That they aimed at the duke of Buckingham, he said, he saw clearly, and he wondered much what had produced such a change since the former parliament; assuring them that the duke had taken no step but by his order and consent; and he concluded by desiring them to hasten the question of supply, "or it would be worse for them."

On the 29th of March he repeated the menace; but the commons went on preparing their charges against Buckingham, declaring that it was the undoubted right of parliament to inquire into the proceedings of persons of any estate whatever, who had been found dangerous to the commonwealth, and had abused the confidence reposed in them by the crown.

Seeing them bent on proceeding, Charles sent down to the house the lord keeper, to acquaint them with his majesty's express command that they should cease this inquiry, or that he would dissolve them; and Sir Dudley Carleton, who had been much employed as ambassador to foreign states, and had recently returned from France, warned them not to make the king out of love with parliaments, and then drew a most deplorable picture of the state of those countries where such had come to be the case. In all Christian countries, he said, there were formerly parliaments; but the monarchs, weary of their turbulence, had broken them up, except in this kingdom; and now he represented the miserable subjects as resembling spectres rather than men, miserably clad, meagre of body, and wearing wooden shoes.

This caricature of foreigners, had it been true, was the very thing to make the commons cling to their freedom, and keep their affairs in their own hands; and as such arguments had no effect, Charles summoned the house to the bar of the lords, and there addressed to them a most royal reproof, letting them know that it depended entirely on him whether he would call and when he would dismiss parliament, and, therefore, as they conducted themselves so should he act. Their very existence depended, he assured them, on his will.

This was language which might have done in the mouth of Henry VIII., who by the possession of the vast plunder of the church had made himself independent of parliaments, and trod on them at his pleasure; but the times and circumstances were entirely changed. The commons had learned their power and the king's weakness, and would no longer tolerate the insolence of despotism. They returned to their own house, and, to show that they were about to discuss the

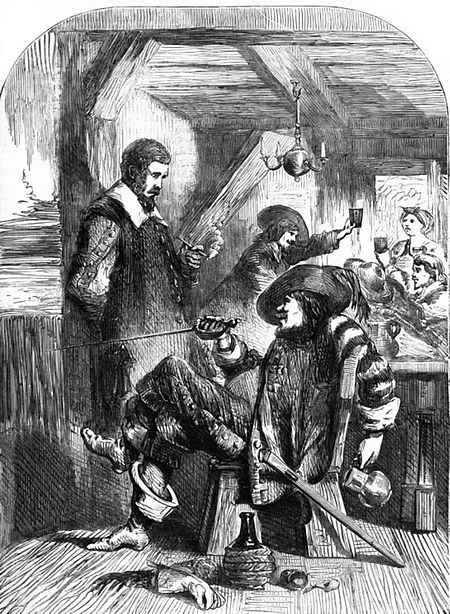

LANDING OF THE PRINCESS HENRIETTA.

As if Charles were actually inspired by madness, at this moment, when he needed all the assistance of the peers to screen his favourite from the impeachment of the commons, he made a direct attack on their privileges. Lord Arundel, the earl marshal, had given some offence to Buckingham, and was well known to be decidedly hostile to him. As he possessed six proxies, it was thought a grand stroke of policy to get him out of the house at the approaching impeachment; and a plea was not long wanting. Arundel's son, lord Maltravers, had married a daughter of the duke of Lennox without consent of the king, and as Lennox was of blood-royal, this was deemed offence enough to involve Arundel himself. He was charged with not having prevented it, but he replied, that the match had been made unknown to him; that it had been secretly planned betwixt the mothers of the young people. This was not admitted, and Arundel was arrested by a royal warrant, and lodged in the Tower. The real offender, if real offence there were, was Maltravers, but it was Arundel's absence which was wanted. The lords, however, took up the matter as an infringement of their privileges; they passed a resolution that "no lord of parliament, the parliament sitting, or within the usual times of privilege of parliament, is to be imprisoned or restrained, without sentence or order of the house, unless it be for treason or felony, or for refusing to give surety for the peace."

They sent an address to Charles demanding Arundel's immediate liberation; he returned an evasive answer: they sent a second address; Charles then ordered the attorney-general to plead the royal prerogative, and to declare the earl marshal as personally offensive to the king, and as dangerous to the state. The peers would not admit the plea, but passed a resolution to suspend all business till their colleague was set at large; and after a contest of three months the king was forced to yield, and the earl marshal resumed his seat in the house amid cheers and acclamations.

But this most imprudent conflict with the peers had another and still more damaging result. The earl of Bristol, who had been so unjustly and ungraciously received, or rather, not received, on his return from his Spanish embassy, to enable Buckingham and Charles to maintain their charge against Spain, had remained an exile from court and parliament, but not without keeping a watchful eye on the progress of events. He was not a man to sit down quietly under misrepresentation and injury; and now, seeing that the peers had roused themselves from their subserviency, and were prepared to take vengeance on the common enemy, he complained to the house of peers that, as one of their order, and possessed of all their privileges, his writ of summons to parliament had been wrongfully withheld. To have withstood this demand at this moment, might have led to a dangerous excitement. The writ was therefore immediately issued, but Bristol at the same time received a private letter, charging him on pain of the king's high displeasure not to attempt to take his place. The earl at once forwarded the letter to the peers, requesting their advice upon it, on the ground that it affected their rights, being a case which might reach any other of them, and demanding that he might be permitted to take his seat in order to accuse the man who, to screen his own high crimes and misdemeanours, had for years deprived of his liberty and right a peer of the realm.

This alarming claim of the earl's struck both the king and Buckingham with terror; and to prevent, if possible, the menaced charge, the attorney-general was instantly despatched to the lords to prefer a plea of high treason against Bristol. But the peers were not thus to be circumvented. They replied that Bristol's accusation was first laid, and must be first heard; and that without the counter-charge being held to prejudice his testimony. Bristol, thus at liberty to speak out, proceeded to town and to the house of peers in triumph, his coach drawn by eight horses, caparisoned in cloth of gold or tissue; and Buckingham, as if to present a contrast of modesty, a quality wholly alien to his nature, drove thither in an old carriage with only three footmen and no retinue.

Bristol charged him with having concerted with Gondomar to inveigle the prince of Wales into Spain, in order to procure his conversion to popery prior to his marriage with the Infanta; with having complied with popish ceremonies himself; with having, whilst at Madrid, disgraced the king, his country, and himself, by his contempt of all decency, and the vileness of his profligacy. He stated that, "As for the scandal given by his behaviour, as also his employing his power with the king of Spain for the procuring of favours and offices, which he conferred on base and unworthy persons, for the recompense and hire of his lust—these things, as neither fit for the earl of Bristol to speak, nor, indeed, for the house to hear, he leaveth to your lordships' wisdoms how far it will please you to have them examined." He went on to charge him with breaking off the treaty of marriage solely through resentment, because the Spanish ministers, disgusted with his conduct, refused any negotiation with so infamous a person, and that, on his return, he had deceived both king and parliament by a most false statement. All this the earl pledged himself to prove by written documents and other most undeniable evidence.

Instead of Buckingham attempting to clear himself as an innocent man so blackened by terrible charges would, it was sought to deprive the testimony of Bristol of all value by making him a criminal and a traitor to the king whilst his representative in Spain. Charles went so far as to send the lord keeper Coventry, a most pliant courtier, to inform the lords that he would of his own knowledge clear the duke, the duke himself reserving his defence till after the impeachment by the commons. Charles not only guaranteed to vindicate Buckingham, but accused Bristol of making a direct charge against himself, inasmuch as he himself had been with Buckingham all the time in Spain, and had verified his narrative on his return. The peers passed this royal charge courageously by; and Charles then ordered the cause betwixt Bristol and Buckingham to be removed from the peers to the court of King's Bench; but the lords would not permit such an infringement of their privileges. They put these questions themselves to the judges—"Whether the king could be a witness in a case of treason? And whether, in Bristol's case, he could be a witness at all, admitting the treason done with his privity?" The king sent the judges an order not to answer these questions, and in the midst of these proceedings the charges against Bristol were heard, and answered by him with a spirit and clearness which appeared perfectly satisfactory to the house. The charges against him amounted to this:—That he had falsely assumed James of the sincerity of the Spanish cabinet; had concurred in a plan for inducing the prince to change his religion; that he had endeavoured to force the marriage on Charles by delivering the procuration; and had given the lie to his present sovereign by declaring false what he had vouched in Buckingham's statement to be true. These were so palpably untenable positions that the house ordered Bristol's answer to be entered on the journals, and there left the matter.

But now the impeachment of Buckingham by the commons was brought up to the lords. It consisted of thirteen articles; the principal of which were that he had not only enriched himself with several of the highest offices of the state which had never before been held by one and the same person, but had purchased for money those of high admiral and warden of the Cinque Ports; had in those offices culpably neglected the trade and the security of the coasts of the country; had perverted to his own use the revenues of the crown; had filled the court and dignities of the land with a host of his indigent relations; had put a squadron of English ships into the hands of the French, and on the other hand, by detaining for his own use a vessel belonging to the king of France, had provoked him to make reprisals on British merchants; had extorted ten thousand pounds from the East India Company; and even charged him with being accessory to the late king's death, by administering medicine contrary to the advice of the royal physicians.

Eight managers were appointed by the commons to conduct the impeachment—Sir Dudley Digges, Sir John Elliot, Serjeant Glanville, Selden, Whitelock, Pym, Herbert, and Wandsford. Digges opened the case, and was followed by Glanville, Selden, and Pym. Whilst these gentlemen were speaking and detailing the ground charges against him, Buckingham, confident in the power and will of the king to protect him, displayed the most impudent recklessness, laughing and jesting at the orators and their arguments. Serjeant Glanville, on one occasion, turned brusquely on him, and exclaimed, My lord, do you jeer at me? Are these things to be jeered at? My lord, I can show you when a man of a greater blood than your lordship, as high in place and power, and as deep in the favour of the king as you, hath been hanged for as small a crime as the least of these articles contain."

Sir John Elliot wound up the charge, and compared Buckingham to Sejanus; as proud, insolent, rapacious, an accuser of others, a base adulator, and tyrant by turns, and one who conferred commands and offices on his dependents. "Ask England, Scotland, and Ireland," exclaimed Sir John, "and they will tell you whether this man doth not the like. Sejanus's pride was so excessive, as Tacitus saith, that he neglected all counsel, mixed his business and service with the prince, and was often styled imperatoris laborum socius. My lords," he said, "I have done. You see the man; by him came all the evils; in him we find the cause; on him we expect the remedies."

The direct inference that if Buckingham was a Sejanus the king was a Tiberius, and a rumour that Elliot and Digges had hinted that in the death of the late king there was a greater than Buckingham behind, transported Charles with rage, and urged him on one more of those acts of aggression which ultimately brought him to actual battle with his parliament. He had the two offending members called out of the house as if the king required their presence, when they were seized and sent to the Tower. This outrage on the persons of their fellow members and delegated prosecutors, came like a thunder-clap on the house. There was instantly a vehement cry of "Rise! rise! rise!" The house was in a state of the highest ferment.

Charles hurried to the house of lords to denounce the imputations cast upon him, and to defend Buckingham; and Buckingham stood by his side whilst he spoke. He declared that he had punished some insolent speeches, and that it was high time, for that he had been too lenient. He would give his evidence to clear Buckingham, he said, in every one of the articles, and he would suffer no one with impunity to charge himself with having any concern in the death of his father. But all this bravado was wasted on the commons: again with closed doors they discussed the violation of their privileges, and resolved to proceed with no further business till their members should be discharged. In a few days this was done, and the house passed a resolution that the two members had only discharged their bounden duty.

At this crisis the earl of Suffolk died, leaving vacant the chancellorship of the University of Cambridge; and Charles, with that perversity which proved his ruin, seized on the opportunity to mark his friendship for Buckingham, and thus to stamp his opinion of the proceedings of the commons, to confer the honour on him. The news of Suffolk's death reached the palace early on Sunday morning, and the next day, about noon, Dr. Wilson, chaplain to Montague, lord bishop of London, arrived in Cambridge, bringing a verbal message from the bishop that the king desired the heads of houses to appoint the duke. These facile gentlemen were very ready to comply, but the fellows and younger members declared that the heads had no more to do with it than they had, and forthwith nominated Howard, earl of Berkshire, without waiting for his consent. On Tuesday morning, however, the bishop of London, with Mason, the duke's secretary, and a Mr. Cozens, arrived with the king's mandate for choosing Buckingham. Then there was a violent strife, the heads of houses and the bishop persuading and intimidating the fellows, and to such effect that at length the election of the favourite was carried by a mere majority of three. There was but one doctor who dared to rote against the duke; and many of the fellows who were utterly opposed to him, hired horses, and rode off out of the way to avoid importunity. Great was the triumph of the royal party when the event was announced. Buckingham presented the messenger who brought him the news with a fine gold chain, and sent by him a letter of thanks from himself, and another from the king, in which he told the heads of houses and the fellows who had voted for the duke that they should be rewarded for it, and that he would ever testify Buckingham worthy of their election. On the other hand, the house of commons passed a resolution that the election of a man under impeachment by them, was an insult to the house, and ordered this resolution to be communicated to the heads of houses, and that they should be called up to answer for their conduct. The king sent them word not to stir in this business, which, he said, belonged not to them but to him; but this resolve was only delayed by the proceedings against Buckingham.

On the 8th of June, a week after his election as chancellor of the University of Cambridge, he opened his defence in the house of lords. In this he had been assisted by Sir Nicholas Hyde. He divided the charges against him into three classes: such as were utterly unfounded in fact; such as might be true but did not affect him; and lastly, such as he had merely been the servant of the king or the executive in. In all the circumstances which could be proved, he merely acted in obedience to the late or the present king, with one exception, the purchase of the office of warden of the Cinque Ports, which he admitted that he had purchased, but which he thought might be excused on the ground of public utility. As to the grave charge of the delivery of the king's ships to the French admiral, he did not mean to go into it, not but that he could prove his own innocence in the affair, but that he was bound not to reveal the secrets of the state; and he pleaded a pardon which had been granted by the king on the 10th of February, that is, four days after the opening of the present parliament.

Thus Charles had kept his word: he had allowed the duke to throw the total responsibility of his deeds on himself, and he had granted him a pardon by anticipation, to forestall the conclusions of parliament. This defence by no means satisfied the commons, and they proceeded to reply; but in this they were stopped short by the king, who the very next day sent a message to the speaker, desiring the house to hasten and come at once to the subject of supply, or that he would "take other resolutions." The commons set themselves, without loss of time, to prepare a remonstrance in strong terms, praying for the dismissal of the favourite; but whilst employed upon it, they were suddenly summoned to the upper house, where they found commissioners appointed to pronounce the dissolution of parliament. Anticipating this movement, the speaker had carried the resolutions of remonstrance in his hand, and before the commissioners could declare parliament dissolved, the speaker held up the paper and declared its contents. The lords, on this, apprehending unpleasant consequences, sent to implore Charles to a short delay, but received the kings energetic answer—"No, not for one minute!"

Thus terminated this remarkable parliament, the second of this reign: such a session as had never before been witnessed in this country. From first to last the actions of Charles were like those of a man driven from his right reason by passion; and the conduct of the commons as the result of a settled determination to maintain its rights; which boded far more than any eye or mind could foresee, but which we, who live after the conflict, perceive clearly to be the commencement of that unexampled warfare which will for evermore display its great lesson to the nations. Charles was the blind maniac of prerogative,—blind to all signs in heaven and in earth; blind to the lurid lights of the lowering sky; deaf to the mutterings of the tempest rising hourly around him. The commons were the steadfast rock rooted in the soul of the people, and impassable to the shocks of regal rage.

Charles was left by his own wild agency to try how his fancied right divine would furnish him funds to discharge his debts at home and his obligations abroad. That he was not insensible to his danger, or to the price which he had paid for the support of his favourite, is made plain to us by Meade, the careful chronicler of the time. "The duke," he says, "being in the bed-chamber private with the king, his majesty was overheard, as they say, to use these words:— 'What can I do more? I have engaged mine honour to mine uncle of Denmark and other princes. I have, in a manner, lost the love of my subjects, and what wouldst thou have me do?' Whence some think the duke meant the king to dissolve the parliament."

But however he might feel this, he was in he disposition to take warning; the spirit and the inculcations of his father worked in him victorious over any better instincts. It was hard for the descendant of a hundred kings, who from age to age had trampled carelessly on popular rights, to give up that comfortable ascendancy to the people. Thousands of men had been arraigned and punished for high treason to kings, but for a king to be arraigned and punished for high treason against the people, could not enter into a kingly head, till such a head had fallen from the block. And towards this great lesson Charles was now driving as urged by a fate. Like the horse which pushes against the knife held to its breast, or the bull-dog which plucked the kettle from the fire because it spurted a boiling drop upon him, and died in a deadly scalding struggle with it, the courage of Charles rose doggedly, unchangeably, against all opposition and auguries, and would have been admirable had it not been exerted to annihilate the liberties of the nation for ever, to triumph over Magna Charta.

No sooner had he dismissed parliament, than he seized the earl of Bristol, and Arundel the earl marshal, and thrust Bristol into the Tower. This bit of petty spite enacted, he set about boldly to do everything that the commons had been striving against. The commons had published their remonstrance; he published a counter declaration, and commanded all persons having that of the commons to burn it, or expect his resentment. He then issued a warrant, levying duties on all exports and imports; ordered the fines from the catholics to be rigorously enforced, but offering to compound with rich recusants for an annual sum, so as to procure a fixed income from that source. A commission was issued to inquire into the proceeds of the crown lands, and to grant leases, remit feudal services. and convert copyholds into freeholds, on certain charges. Privy seals were again issued to noblemen, gentlemen, and merchants, for the advance of loans, and London was called on to furnish one hundred and twenty thousand pounds; and as if the king already feared that his arbitrary acts might produce disturbance, under the plea of protecting the coasts, he ordered the different sea-ports to provide and maintain during three months, a certain number of armed vessels, and the lord lieutenants of counties to muster the people, and train troops to arms to prevent internal riot or foreign invasion.

At the moment that the king was thus daringly setting both parliament and the country at defiance, came the news that a terrible battle had been fought at Luttern betwixt the Austrians under Tilly, and the protestant allies under Charles's uncle the king of Denmark; that the allies were defeated and driven across the Elbe; all their baggage and ammunition lost, and the whole circle of Lower Saxony left exposed to the soldiers of Ferdinand. This was the death-blow to the cause of the elector palatine. But Charles seized on the occasion to raise money by a fresh forced loan on a large scale, on pretence of the necessity of aiding protestantism, and as if to make the lawless demand the more intolerable, the commissioners were armed with the most arbitrary powers. Whoever refused to comply with this illegal demand, they were authorised to interrogate on oath, as to their reasons, and who were their advisers, and they were bound by oath never to divulge what passed betwixt them and the commissioners.

Charles issued a proclamation, excusing his conduct by alleging that the necessities of the state did not admit of waiting for the reassembling of parliament, and assuming his loving subjects that whatever was now paid would be remitted in the collection of the next subsidy. He also addressed a letter to the clergy, calling on them to exhort their parishioners from the pulpit to obedience and liberality. But such were the relative positions of king and parliament, that people were not very confident of any speedy grant from that body, and the good faith of both Charles and his favourite had become so dubious, that many refused to pay. The names of these were transmitted to the council, and the vengeance of the court was let loose upon them. The rich were fined and imprisoned, the poor were forcibly enrolled in the army or navy, that "they might serve with their bodies, since they refused to serve with their purses."

In vain were appeals made to the king against this intolerable tyranny, he would listen to no one. Amongst the names of those who suffered on this occasion, stand those of Sir John Elliot and John Hampden, as well as of Wentworth, soon, as Strafford, to become a proselyte of absolutism.