Cyclopedia of Painting/Brushes

BRUSHES.

Cheap goods of any kind never reflect credit on the maker. Neither do they give satisfaction to the consumer or dealer. It requires skill and art as well as quality of material to produce high grades of goods, and such must always bring their price and never fail to give satisfaction. For this reason, the intelligent, practical and thoughtful workman will always look for the best tools. Good bristle brushes cannot be made of any substitute for imported bristles, and cheaper grades are always produced by adulteration and mixtures. The cheapening of goods is generally done so that

it shows least to the eye, in the center of the brush, and covered by good quality to make the goods as marketable as possible. Such goods cannot be expected to be durable or give satisfaction.

First-class goods can also be ruined or lose half their value if they are not properly cared for. Paint and varnish, as well as calcimine and whitewash brushes, should never be allowed to stand on the ends of bristles over night, but should always be cleaned thoroughly before quitting work, and carefully hung up, paint and varnish brushes in oil or varnish, and calcimine and whitewash to dry. It will injure any brush to let it remain in water. Should paint, varnish, leather-bound whitewash or wall brush be found that has become loose from shrinkage, take a tablespoonful or so of water, open the brush and pour the water into the center. This will swell the parts and make the brush as firm as when first made.

New brushes when first put in work are apt to shed any loose bristles that have not been fastened when made, and while such loose bristles are always cleaned out before the goods are put up for market, not all such loose bristles or hair can be cleaned out, and such are sure to come loose when the brush is first used. This defect will cure itself in one day's use.

Do not condemn the maker if one brush is brought back by a practical workman, who possibly has had one or more brushes out of the same dozen that were all right and gave perfect satisfaction, but look for the cause or defect in the user. Remember that goods are made up in large quantities, and when the bristle is prepared it is in large batches. It must naturally follow that if one brush, or one dozen, or any quantity of such a lot is good that all must be, or if one is bad all must be so.

The greatest annoyance that manufacturers have to contend with is the improper or careless use and care of good, first-class brushes.

Good goods of all kinds are a credit to the manufacturer, give satisfaction to the mechanic in use, and pleasure and profit to the dealer to sell. They are sure to bring their own reward.

Brushes are made of bristles and of hair, bound to a handle by cord, wire, metal stamped to imitate wire, tin, copper and brass. The oval and round paint and varnish brushes are generally bound with cord, wire or its imitations, and copper and brass. The flat bristle, fitch, badger, bear and camel's-hair brushes with tin. The ordinary paint brushes contain the inferior or coarser grades of bristles, the varnish brushes are selected or finer qualities. The oval and round brushes are numbered by the brush-maker to designate sizes, from No. 6 down to No. 1. thence from one to 000000. For carriage painting the sizes between one and four naughts are considered best, the smaller ones may be used, but it is advantageous to use as large a brush as possible on most of the work. Small brushes called tools are numbered from 1 up to 10, the latter being the largest. Brushes are generally used in sets, as, for example, in painting a body or gear, a large brush for laying the paint would be used, and a small tool for cleaning up around the moldings, nuts and bolt-heads. It would be an almost endless task to illustrate and describe all of the many varieties of paint and varnish brushes, and a few of the principal ones only will receive attention here. Russia is the great bristle growing country, and her exports reach as high as 5,000 tons of this commodity every year. Hogs in countless herds roam the deep Muscovite forests, where the oak, the pine, the beech, larch and other nut bearing trees cover the ground with acorns and nuts to the depth of a foot or more. But these swine are not all of value for their bristles. The perfect bristle is found only on a special race, and that race fattened in a certain way. On the frontiers of civilization all over the Muscovite territory are the government tallow factories, where animals reared too far from the habitation of men to be consumed for human food are boiled down for the sake of their fat. The swine are fed on the refuse of these tallow factories at certain seasons, and become in prime condition after a few months' feeding. It is from these animals that the bristles of commerce mainly come. When the swine are fattened, and their bristles in fine color, they are driven in kraals so thickly that they can scarcely stand—irritated and goaded by the herdsmen till they are sullen with rage—kicking, striving, struggling and scrambling together in feverish rage, they are seized one by one, by the kak koffs, a class of laborers educated to plucking swine, and their bristles pulled out by the roots. The perspiration into which the poor creatures are thrown by their exercise causes their bristles to yield easily. The process is pleasant neither to the eye nor the ear. The hog strenuously resists with loud outcries, and vehement opposition. It does no good. Once seized, he is instantly divested of

his clothing and then immediately released, goes grunting off to the woods.

The so-called French bristles are principally from Russia stock, cleaned and bleached to render them white and exceedingly elastic, yet soft as an infant's hair. From these are made the fine pencils of the artist. Length, elasticity, firmness and color are elements that constitute their excellence, and the bristle expert can readily assort them for their special uses.

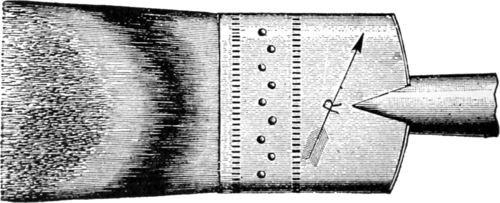

The ordinary paint brush for general work is made either from selected Russia bristles, or with an inferior gray center, inclosed by fine white bristles. Carriage and wagon painters usually select the best Russia bristles, and the size known as 0000 is used for rough-stuff and foundation coats, while the house painter would choose a larger one possibly. A new brush of this description will not work well unless bridled, that is having an extra binding added, and this may be done in several ways.

By winding a strong cord around the bristles to about the middle of the same, or, as far from the original binding as desired. By covering a portion of the bristles with leather stitched on tightly. By wrapping a piece of muslin around the brush, then tying a cord at the center of the bristles turn the muslin back and tie it securely to the handle. By using a patent metallic band or binder, and by other means, the object being to shorten the exposed bristles until the brush is partly worn down, when the extra binding may be removed.

Badger-Hair Varnish Brush. The badger-hair brush is next in importance. It is well bound in tin, hair set in glue, handle nicely japanned, and chisel-pointed. For varnishing small panels or parts of a body it has no equal. The best badger-hair is imported on the skin from Germany and Russia.

Camel's-Hair Brush. For laying fine color no better brush can be had than the camel's-hair brush, called by some mottlers, by others blenders, and again by others spalters, each term, however, is foreign to the American painter, and the camel's-hair brush is by far the most appropriate, and most commonly used. The hair used in these brushes, however, is not all taken from the camel, much of it being from the tail of the Russian brown squirrel. The hair is first cut from the tail with scissors, the wool or under fur combed out, and then tied in bunches ready to be straightened. This requires skill and practice. The hair is placed in metal cups having a thick, loaded bottom, and by quick motion of the hand, drummed on the bench for a considerable time, until the pointed or fine ends are all even with each other. In the process of cutting and cupping the lengths are kept separate as far as possible. The hair is now ready for the brush-maker, who cups and combs it out, weighs the quantity required, and places it into the ferrules or tin bands. It requires skill to handle the short, slippery hair and keep it in shape. It is not many years since work of this kind was all done abroad. Now, it is claimed by experts that the American manufacture of most kinds of brushes excels the foreign goods. The chiseled camel's-hair brush is something entirely new, and is certainly a very fine brush and well calculated to do smooth, particular work. Another class of these goods are made extra thick and from picked camel's-hair, the binding of brass having its edge turned under, which gives additional security to the hair and prevents cutting the hair on the edge of the binding, which too frequently happens.

Camel's-Hair Tool. Small brushes, called tools, made of camel's-hair are used for blacking irons, lacquering, and other work of like nature. The next brush to be considered is the camel's-hair duster, a tool used mostly by gilders in removing the loose gold leaf from their work when gilding. These are bound in split quill and fastened with wire. The next to claim attention is the gilder's camel's-hair tip. This is made by laying a thin layer between two pieces of card-board and gluing the whole firmly together; it is used to lift and carry to the work the pieces of gold leaf. A slight moisture or stickiness is given the hairs by simply passing them over the face or hair of the head, and then the gold leaf can be easily lifted from the cushion on which it has been cut and dexterously laid upon the gilding size.

For painting walls a large flat bristle brush is used, made of all white bristles, bound in copper, brass or galvanized iron. It has always been a difficult task to make a wall brush to stand the hard usage it generally receives, but now that machinery of the most approved pattern has been introduced in the brush factory these brushes are made under warranty.

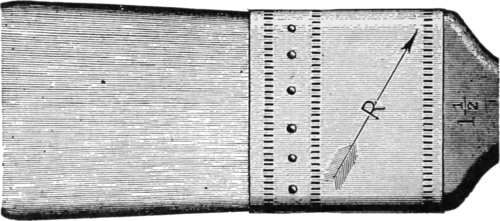

Flat Bristle Varnish Brush. These are made of the best white bristles, set with glue, doubled nailed, soft yet very elastic, with chiseled points. They are considered the best brush made by many of the best varnishers. They are put up in sets from one inch in width to three inches. These brushes, if used with care, will wear a long time.

Flat Chiseled Brush. Flat paint brushes are preferred by some. These are chiseled or ground off on the sides to form a thin edge. They are bound in tin or rubber and are graded in size by their width.

Flattened Round Tool. This is superior to the sash tool for cleaning between the spokes, and for finishing around the various parts of the gear. This brush is tin-bound, well riveted, and the bristles are set in glue, which is insoluble in turpentine and oil, and therefore superior to the cement used by some brush-makers. The size best suited for the carriage painter is about one and a quarter inches in width. This is also an excellent tool for varnishing, in trimming up around moldings.

Fitch-Hair Brush. This brush was formerly in extensive demand as a varnish brush but of late years the badger has supplanted it, owing, in a degree, to the numerous imitations in the market, and also to the liability of the rotting away or breaking of the hairs when in use. The hair is mostly from the tail of the skunk.

Sash-Tool. A sash tool, or small brush, is necessary as an auxiliary to the large brush, for cleaning up in corners, etc.

Oval Varnish or Paint Brush. As the under parts of a carriage are not rubbed with lump pumice-stone, the same as the body, the paint must be applied with greater care, and the 000 oval brush will work best, laying the paint smoothly and leaving but few, if any, brush marks. The chiseled brush should always have preference over a partly worn one, as the bristles are as a rule softer upon their extreme ends.

The Care of Brushes. However good a brush may be it will soon be ruined unless it is properly treated when out of use. The following hints will suffice as a guide in this respect:

Writing Pencils. Wash in turpentine until quite clean, and if they are not to be used for some time, dip in olive oil and smooth from heel to point.

Stipplers. Wash thoroughly in pure soap and hot water, rinsing with cold water. Place point downwards to dry.

Varnish Brushes. The best method of keeping varnish brushes is to suspend them in the same description of varnish as that they are used for. As this is not always possible, boiled oil may be used instead.

Brushes made for Use in Color should first be soaked well in water to swell the bristle in the binding. This applies also to whitewash brushes which are bound either by wire or leather.

A Brush after use should be thoroughly cleansed out in turps or soap and water. If left in water any length of time they are liable to twist, and the bristles lose their elasticity.

A Brush made for Paint should not be used in varnish, the spirit of which dissolves the cement with which it is set, and loosens the bristles. When a ground brush has been well worn down in color, it may be used in varnish.

Varnish Brushes when not in use should be suspended in either varnish or oil, the brush not resting on the bristles. No brushes should on any account be kept in turpentine.

Stippling Brushes should be well cleaned and dried after use, the bristle being carefully kept from crushing; a box in which they can be slid, allowing the bristle to hang downwards is recommended.

Should a Brush become quite hard with Paint it should be soaked for twenty-four hours in raw linseed oil, after which time in hot turpentine.

Cleaning Paint Brushes. All brushes, after being used, should be carefully cleaned. This is best effected by immersing the hair of the brushes in a little raw linseed oil, the oil should afterwards be washed out with soap and warm water, till the froth which is made by rubbing the brushes on the palm of the hand is perfectly colorless. The brushes should next be rinsed in clean water, and the water pressed out by a clean towel. The hair should then be laid straight and smooth, and each brush restored to its proper shape, by passing it between the finger and thumb, before it is left to dry. Care should be taken not to break the hair by too violent rubbing, as that would render the brushes useless. Many painters use turpentine instead of linseed oil in the cleaning of brushes, it effects the object more quickly, but the only use of turpentine that should be permitted is to rinse the brushes in it slightly when it is required to clean them quickly, but on no account should they be permitted to remain soaking in turpentine, as this practice is certain to injure the brushes, rendering the hair harsh and intractable, and frequently dissolving the cement by which the hair is held in the socket of the handle.