Dutch Art in the Nineteenth Century/The Romanticists

CHAPTER III

The RomanticistsAry Scheffer was born at Dordrecht in 1795. His father, Jan Baptist Scheffer, was a German, a native of Mannheim and a pupil of Tischbein the portrait-painter. He was attached to the Court of King Louis Napoleon and died in Amsterdam in 1809. He made a name as a painter of portraits and interiors. He married at Dordrecht the daughter of Arie Lamme the scene-painter, one of Joris Ponse's pupils, who also distinguished himself by his excellent copies of Albert Cuyp and sometimes himself painted pictures in the same manner. Cornelia Lamme seems to have been a woman endowed with beauty, charm, artistic talent and a strong personality, to whose initiative her three sons owe their training and a great part of their fame. History, including the history of painting, shows a whole array of mothers who, through their firm belief in their sons' talent, their indefatigable material solicitude, their utter self sacrifice, have smoothed for their sons the difficult road of art. Ary received his first training at his father's hands and, when the latter died, at a time when the art of painting in Holland had sunk very low, Mrs. Scheffer resolved to take her children to Paris, where Ary and Henri could receive a good education. In 1810, the year before their departure, when Ary was in his fifteenth year, he exhibited in Amsterdam a portrait that was ascribed to the brush of a past master in the art. It has been regretted, by Frenchmen as well as by ourselves, that he did not remain in Holland and paint in accordance with the traditions of his own country. But, at that time, when all eyes were turned to Paris, it was only natural that those who could should make for this centre of civilization and refinement. In any case, it was not easy for the unknown Dutchman, with his defective education, to conquer a place in the city of those experts in technique, Ingres, Delacroix and Géricault; and, until he made a name with his Gretchen at the Spinning-wheel, his lack of a firm groundwork of knowledge often caused him to be looked upon as an amateur or dilettante painter.

In the meantime, he exhibited, in 1825, a portrait of M. Destuit de Tracy which was approved in every respect and considered a master-piece of draughtsmanship. And, after his Defence of Missolonghi, in which he employed the palette of Delacroix, after The Suliote Women, in which, while adopting the same colouring, he first displayed the feminine charm of his talent, he exhibited, in 1831, the Gretchen aforesaid, one of his best works, regarded by some as his master-piece, a work, at any rate, with which he secured a place of his own in the painting world of Paris. The picture is well known through the reproductions. It was admired for the delicacy of feeling, the expression, the composition and it was considered affecting, as a whole. It was said that no one had interpreted Goethe's Gretchen as Ary Scheffer had done: no painter, no poet, no actress. Heinrich Heine, who wrote his impressions of the Salon of 1831 in the Allgemeiner Augsburger, devoted a whole chapter to Gretchen at the Spinning-wheel and to its fellow-picture, a Faust, which was not so greatly admired by the painters, but which roused Heine's enthusiasm; he called it eine schöne Menschenruine:

- "One who had never seen any of this artist's work," he wrote, "would be at once struck by a certain manner that speaks from his arrangement of colours. His enemies declare that he paints only with snuff and green soap. I do not know how far they do him an injustice. His brown shadows are often affected and hence miss the Rembrandt effect of light intended. His faces mostly display that fatal colour which has so often made us take a dislike to our own face when, after long sleeplessness, we look at it in those green mirrors which we find in any inn at which the diligence stops in the morning …

- "If we look into Scheffer's pictures more closely and longer, we become familiarized with his mannerism, we begin to think the treatment of the whole very poetic and we see that a serene mood peers through these melancholy colours like sunbeams through the clouds …

- "Really, Scheffer's Gretchen is indescribable," continues Heine, a little lower down. "She has more mind than face. It is a painted soul. Whenever I went past her, I used involuntarily to say, 'Liebes Kind!' A silent tear rolls down the pretty cheek, a dumb tear of melancholy."

The women especially doted on Ary Scheffer, so much so that it became an act of courage to publish any hostile comment on his work. They recognized the heart in the painter and fell into ecstasies over his sensitive and emotional nature. "Une larme aux yeux ne ment jamais," says Alfred de Musset; and the somewhat feminine Scheffer, the man of sentiment, the man grown up in the mutual cult of mother and son, the man who never really knew what it was to be young, the man of melancholy poetic ideas, passionless and devoid of real sorrow, was just the man to draw that tear.

He understood the emotional side of painting; what he lacked was technical knowledge. And yet, notwithstanding his deficiency in that pictorial quality which we Dutch regard as the one and only essential of good painting, notwithstanding the feeble sentiment and often somewhat barren lines of his pictures, this painter of mixed Dutch and German origin, brought up from his childhood under the great French masters of romanticism, has always represented to us an important talent. It is a talent that stands, for the most part, outside the Dutch tradition, even though foreigners are inclined to see a certain striving after Rembrandt effects in the arrangement of the light. And the golden brown that may be so looked upon is no doubt far preferable to the feeble brown medium which one perceives glancing everywhere through the pale colours; and, though this blends best with the pale blues of his Gretchens, it makes the facial colouring seem very unheimisch.

When Scheffer came to Holland in 1844 as a famous man, he wrote, after visiting the Mauritshuis:

- "I have seen wonderful pictures of the old Dutch school. Meanwhile, I am beginning to have a higher opinion of my own talent … I believe that I have touched a string which the others have never played upon."

Therein lies his merit.

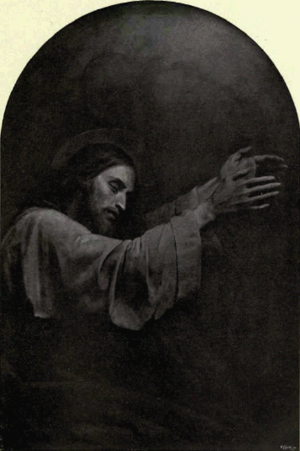

The two large pictures in Boyman's Museum, Count Eberhard of Würtemberg cutting the Table-cloth between himself and his Son and Count Eberhard by the dead Body of his Son, life-size subjects taken from Uhland's ballad, are painted under Dutch influence in the matter of colour; but this causes us to miss the atmosphere all the more. Scheffer was more powerful in pictures which he painted from nature, such as the portrait of Reynolds the engraver, in the Dordrecht Museum, which, with its fluently-painted design, seems inspired by the English painters. Towards the end of his life, in painting his biblical subjects he underwent the influence of the Italian masters, which produced the more vigorous colour-scheme and the more positive, although still very sensitive conception of the Christ bearing the Cross at Dordrecht.

To many and also to those Dutch painters who are still able to take account of the works of the romantic movement his Paolo and Francesca is his master-piece. The well-known engraving does not do justice to this picture, whose value consists in the vigour of the diagonal line by which the painter lets the figures soar on high. It is well painted and is not so shadowless as his Gretchen at the Fountain which, like the Paolo and Francesca, is in the Wallace collection and which, in the arrangement of its lines, suggests a cartoon by Overbeck.

The sensitiveness of Scheffer's character is easily perceived in his work. But in daily life he was so gentle that he could not endure to see a cloud or a wrinkle on the faces of those who were with him. Many abused this quality of his, so that he was forced to work ever harder in order to satisfy the many demands upon him. His benevolence knew no bounds nor did he ever spare pains to assure his mother's comfort.

His studio was difficult of entrance. Mrs. Grote, who is not always to be trusted in her remarks upon his work, tells how he refused admission to almost everybody. Still, he sometimes yielded to the prayers of his numberless admirers of the other sex. Then, on a Sunday morning, everything would be prepared; the visitors entered with hushed voices, as into a church; an organ played in the distance … but the painter himself, meanwhile, was riding his horse in the Bois!

Ary Scheffer died at Argenteuil in 1858. His brother Henri, who was also a pupil of Guérin's, was thought by some to be the better painter, although he achieved nothing like the same celebrity. His Charlotte Corday, an excellent painting, in the Luxembourg, was copied there no fewer than twelve hundred times before the year 1849. There is a Lying-in of his at Boymans' Museum. More in Ary's style is his Joan of Arc in the historical collection at Versailles; but he excelled most of all in portrait-painting. Ernest Renan married his daughter.

Generally speaking, Ary Scheffer exercised no great influence upon the Dutchmen of his time: the strongest of them avoided his influence rather than fall under it. Nevertheless, it may be said that the same emotionalism that characterizes the work of Ary Scheffer is repeated sporadically, in other forms, in the painting of a later date, including the art of our own country. And, although the figure of the great Dutch master, Jozef Israëls, is too vigorous to allow of a comparison, still it was his same seeking for poetry, in another domain, that made Duranty, the French critic, say of his Alone in the World that it was painted d'ombre et de douleur. And do we not sometimes find moments in Toorop which Scheffer, had his line been firmer, would have loved to paint? And, generally speaking, the younger generation of painters often seems to exhibit a reaction against a landscape which it considers not sufficiently thoughtful or, rather, not sufficiently literary.

Thomas Simon Cool, born at the Hague in 1831, was an exponent of a more vigorous romanticism. In 1853, he painted his Atala with its life-size figures, a bold feat for a youth of two and twenty; in 1859, his Last of the Abencerrages. Standing before the Chactas in the former picture at the Hague Museum, we find it difficult to imagine what the painter could have seen in this subject. And yet, though we may now consider it an unattractive picture, it was described in its time as a promising work by a young painter and was thought much of in Paris also. And, even now, notwithstanding the emptiness of the composition and the harshness of the colouring and the workmanship, it shows signs of conviction. Later, his art turned in a more national direction: he took to painting portraits and intimate scenes of Dutch life. But he was never certain of himself, never satisfied with himself. Towards the end of a very short life, he became drawing-master at the Military Academy, where he did well and was held in high account. He died, suddenly, in 1870.

Another and even shorter-lived artist, Lodewijk Anthony Vintcent (1812-1842), never turned his back upon romanticism, in which lay all his strength and all his weakness. He worked first under B. J. van Hove and later under Cornelis Kruseman. He excelled in romantic little genre-pieces: Savoyards, with eyes of exaggerated size, and the like. His master-piece is said to be The City Apothecary, which was painted in the cholera year and represents a crowd of sick and poor waiting for medicines. The grouping of the figures is lifelike: two dogs are fighting for a bone in the foreground; round the corner, in the distance, in a street drawn in fine outline, is a hearse. They say that Vintcent was slightly colour-blind he confused red and green and that this defect was not apparent in the grey-brown tones of this particular picture, which harmonized so well with the subject. Still, these genre-pieces do not make the romanticist. It was rather the feeling, the combination, the conception, the gruesomeness, as in the case again of his illustrations to Macbeth, that gave the necessary suggestiveness. And yet we cannot believe, when we contemplate the false and sentimental feeling displayed in these Savoyards with or without marmots or mousetraps, that, even if he had lived, the young painter would easily have overcome this romantic condition of soul.

The Rotterdam history-painters, Willem Hendrik Schmidt and Jacob Spoel, were of much more importance, in their day, than Vintcent. The former was the intimate friend of Bosboom, who nursed him through his last illness; he was also the master of Christoffel Bisschop and was generally so honoured that he used to be ironically described as the Allah of Dutch painting, with Spoel, his pupil, for his prophet. This celebrity extended beyond his own country, so much so that, when he showed The Raising of the Daughter of Jairus at Cologne, his work was spoken of as the first in the exhibition and Degas' Cain and Abel as the second. He was born in 1809 at Rotterdam, received his first lessons from Gilles de Meyer, another Rotterdammer, who was more of a teacher than an independent artist, for the main part formed himself and, later, in 1840, acquired, in the museums of Düsseldorf, Berlin and Dresden, that culture which cannot be denied him. When he died, in 1849, at Delft, where for some years he had taught drawing at the Training-school for Engineers, people wrung their hands in despair for the future of Dutch painting after such a loss.

He is said to have possessed an original manner, to have succeeded in giving colour, dignity and charm to his works, especially in the painting of fabrics and all sorts of accessories, which reminded one of the old masters. And yet how intensely tedious are just those very qualities in the painters of so-called old-Dutch interiors! It would appear as though they all excelled in this, for we become sick and tired, in these shiny little pictures, of those "excellently limned " accessories and stuffs and silks. Still, Schmidt demanded more of art and here we see his romanticism come peeping round the corner began to feel that art must become something nobler and more exalted. We, who really known little of his work besides the picture of the monks in Boymans' Museum, in which naturally we cannot expect to find any lively colouring, see in him merely a good painter, with a rather wearisome method, a narrow modelling and a notable lack of harmony. His great, if short-lived fame must have rested on more important work than this.

(Historical Gallery, the Hague: the property of Mr. J. C. van Hattum van Ellewoutsdijk)

It would appear that the history-painter Spoel is a little closer to us than his master. This impression is perhaps due to the engraving of his Procession of the Rotterdam Rhetoricians on the occasion of the progress of the Queen of England, 19 March 1642, which was published as a prize of the Society for the Encouragement of the Plastic Arts and distributed in every corner of our country. Westrheene says of the original picture that it unites all Spoel's good qualities and, moreover, displays a strength of colour, an ease and firmness of touch of which he did not often give proof. Jacob Spoel was born at Rotterdam in 1820 and died in the same town in 1868.

Another contemporary of Jan Kruseman, of Klaas Pieneman, of Hendrik Schmidt, of Van de Laar is Petrus van Schendel, who was born in 1805, in a little village near Breda, and studied at the Antwerp Academy under Van Bree. He resided consecutively at Rotterdam, Amsterdam, the Hague and Brussels, painted portraits, historical pictures and genre-pieces and excelled in his little candle, lamp or torch-light scenes, which were thought much of in his day. As an historical painter, he did not object to big canvases: his Birth of Christ measured three Dutch ells by four. The distance between Van Schendel and Da Vinci is great, but he had one thing in common with Leonardo: the love and success with which he practised the science of mechanics. He patented, among others, an important improvement in the propelling of locomotives. Petrus van Schendel died in 1870.

A much more genuine adherent of the romantic movement was Jan Hendrik van de Laar, born at Rotterdam in 1807, a pupil of the miniature-painters C. Bakker and G. Wappers. Although, once in a way, he felt drawn towards historical subjects, as when he painted an Heroic Death of Herman de Ruiter, he preferred to move among the romantic episodes of Walter Scott or the romantic poems of Tollens, who provided the subject of his picture in Boymans' Museum. And yet his art has really as little in common with the romantic movement as has Tollens' poem. Van de Laar's Divorce overflows with middle-class sentimentality, with unnatural, feeble staginess. He died in 1874.

This is how things stood in those days: as in Belgium, men were genre-painters in the style of the old masters; or historical painters but here Belgium had the advantage, inasmuch as she shared French ideas more strongly and therefore was more powerfully moved or painters of biblical subjects and here, again, Belgium had the advantage, inasmuch as she was a Catholic country and her painters therefore were bound to observe a certain decorum and found a place for their work in the Catholic churches;[1] or else and in this they were always more or less excellent they painted portraits, or they painted fashionable interiors, which were generally somewhat sugary and insipid, or they painted landscapes but this was a separate tendency or else they painted all these subjects by turns. We had no Leys, who united colour and style in his renascence, even though Huib van Hove, in his little vistas, often gave good evidence of these two qualities; with us, everything was covered with a sauce of romanticism, which expressed itself in somewhat uncouth contrasts and which showed a decided preference for scenes with monks in them. One of the most sickly and self-satisfied instances of this is a boudoir with a lady and a monk behind her, by Charles van Beveren (1809-1850), that feeble painter who is so richly represented in the Fodor Museum. Schmidt also shared this predilection, as witness his Five Monks in Meditation at Boymans' Museum; and even Bosboom, that always eminent and distinguished painter, who from the beginning saw his way clear before him, took part in the fashion in his grand manner with Cantabimus et psallemur and The Carmelite playing the Organ.

The painters of that time, including Cool and Van Trigt, nearly all began by sacrificing to romance or history, although many of them soon returned to the traditions of their race. The Mæcenases asked for historical painting. Amsterdam, the ever serious city, in whose daily life nature does not play so great a part as in that of the Hague, continued to place before the painters what it considered to be a useful and worthy aim.

This historical romanticism is displayed in the most comical and, at the same time, in the most surprising light in many of the little pictures in the Historical Gallery, the outcome of the running commission given by Mr. de Vos, to which any painter could contribute lavishly and to which, although the payment was but modest, a large number of painters did contribute with commendable readiness. For it was as sure as that twice two are four that whosoever stood in need of ready money at that time would paint one of these pieces in a day or two, although there are a few fortunate exceptions.

The contents of this Historical Gallery, now accommodated in the Municipal Museum of Amsterdam, were painted between 1848 and 1863 to the order of Mr. J. de Vos Jzn., of Amsterdam, a lawyer and a well-known collector, who, in addition to the 253 little pictures, all of the same size and shape, which form the gallery, possessed an important collection of which the acme consisted of drawings by the old Dutch masters, now partly housed in the Rijksmuseum. The historical plan, embracing the whole national history from A. D. 40 to A. D. 1861, the year of the great floods, was, if am not mistaken, arranged with much taste and insight and described in the catalogue by a well-known author, Mr. Jacob van Lennep.

All that remains of any value to posterity, besides an attractive lesson in the history of the motherland for the youth of Amsterdam, is represented by the pictures of Allebé, Alma Tadema and Jozef Israëls and the twenty-six pieces by Rochussen, which excel in colour, style and, in the case of the last, in unity of treatment and great facility. Johannes Hinderikus Egenberger (1822-1897), first a professor at the Amsterdam Academy, afterwards director of the Academy at Groningen, divided the lion's share with Bernardus Wijnveldt Jr. (1821-1902), who succeeded him in the former appointment. Their contributions, except in those cases where Egenberger confined himself to the eighteenth century, in which he is sober and deserving, all belong to the most violent kind. The diagonal lines of the battlesome arms in The Heroic Death of Jan van Schaffelaar are perhaps the most characteristic instance of that rude, theatrical system of historical painting which, like popular historical melodrama, is content to emphasize the hero, the traitor or the coward without troubling about the claims of the art concerned. As for the Kenau Hasselaar painted in collaboration by the two artists for the Town-hall at Haarlem, the violence of the Dutch Amazons, in view of the nature of the defensive weapons employed, is well worthy of the descriptive pen of a Huysmans.

In the midst of all these painters bound to their period, in the midst of so many mediocrities, in the midst of a long array of "famous masters" whom we should nowadays find it impossible to enjoy, De Bloeme stands apart as a sturdy painter, showing neither the influences of his own time nor those of the seventeenth century, but entirely himself, honest and simple. Born in 1802 at the Hague, where he died in 1867, Hermanus Anthonie de Bloeme started under J. W. Pieneman, working in his studio at the Hague and afterwards following him to Amsterdam when Pieneman was appointed director of the Academy. It was inevitable that he should sacrifice to the spirit of the time and begin by painting historical, followed by biblical subjects, of which his Mary Magdalen is considered the best. Nor do I see any reason to believe that he excelled his contemporaries in this regard, for his best portraits also were painted during the last twenty years of his life. What was most remarkable at that period was that he did not go to Italy in search of what he could find at home and this is the more noteworthy inasmuch as the fact, fortunate for him is it was, arose not so much from any convinced idea as from his strong affection for his parents' house and its ways; nay more, when he had to take part in the great competition at the Amsterdam Academy, he purposely sent in his Adam and Eve by the body of Abel in an unfinished state to escape an award which would have taken him for four years far from home. Probably the sheer artistic merit which he so unconsciously betrayed in a bad period is partly due to this, even though it is also probable that he brought home an occasional idea from his shorter journeys. For it must be admitted that the delicious Portrait of a Lady in the Hague Museum and that of Baron van Omphal in the Rijksmuseum, his best portraits, show some conformity of conception with a portrait by Gallait in our Municipal Museum, even though it be true to say that the comparison is to the disadvantage of the once so renowned Belgian. The drawing is thoughtful and compact, without the superfluous flourish with which his contemporaries used to fill in their portraits. Moreover, the attitude of the head in the portrait of Miss Huyser above-mentioned displays an engagingness which we do not expect to find in that period. De Bloeme's colouring is simple and refined, as is his workmanship; and everything is so nicely balanced that we forget to analyze. He was not easily pleased and would rather smear out an almost completed portrait with a couple of smudges than deliver it against his will, a habit which necessitated endless patience on the part of his sitters. We are told how, after many sittings. Princess Marianne of the Netherlands, on paying her last visit to the studio at the appointed hour, found the painter engaged in smudging out her portrait, whereupon there followed a "scene" which did not subside until mutual promises had been exchanged to start again from the beginning.

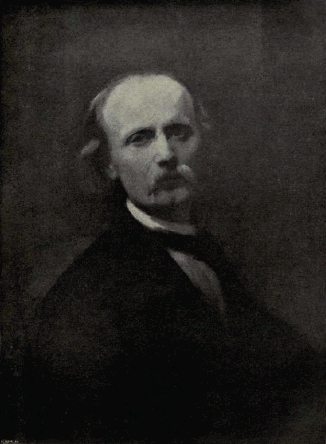

There is a great contrast in temperament between the simple Hague portrait-painter and the somewhat younger romanticist Johan George Schwartze, his rival in Amsterdam. Thanks to a wider conception, to a certain tendency towards romanticism, to a search after not only the outer but also the inner aspect of his sitters, Schwartze may be said to have aimed higher in his portraits than the less complex Hague artist. And, in view of these qualities, one would be disposed at once to allot the first place to this Rembrandtesque painter, whose Portrait of Himself is in many ways so charming, so distinguished, so soulful. But, when we look at it again, the thing becomes different: from under that soulful performance peeps something weaker, even though it be a very lovable weakness, against which De Bloeme's simpler excellence is well able to hold its own.

The fact that Schwartze, for all his great and attractive qualities, did not exercise a greater influence over his younger contemporaries is perhaps due to this very inclination towards romanticism, to this very striving to imbue his portraits with characters. Mental and moral characteristics too strongly emphasized can captivate us, in the long run, only when they are there unconsciously, or as an important piece of painting, or at any rate executed in a certain style. When Jozef Israëls painted the portrait of his brother artist, Roelofs the landscape-painter, full of suggestion as it is, while seeking for the man under the social varnish, he emphasized no single quality at the expense of any other; perhaps only a painter could recognize the painter in the eyes of the portrait; and even this is quite subordinate to the intense life that breathes through the wide-open nostrils, under the high forehead, in the eyes beneath the bushy brows. Whereas, when Schwartze painted the portrait of Professor Opzoomer, the philosopher, a portrait the conception of which was so greatly admired by the professor's friends because Schwartze painted the thinker as Faust, in a moment of despair, of powerlessness, he was condemned by a later generation, which sees that there is something so theatrical in the attitude, something so much of an actor playing his part, that the portrait resembles a rhetorical phrase rather than a human being.

We are not saying that Schwartze was not an excellent painter or that in him, as in the later Lenbach, the painter was sacrificed entirely to the psychologist; for, although of German origin, he shows in his painting the pure Dutch characteristics: fine, warm shadows, strong half-tones and boldly modelled light, solid workmanship, thought in the execution, fulness, completeness. His own portrait is certainly one of the very finest expressions of Dutch romanticism; the portrait of his wife, with which he made a great success at the time, possesses that charm which we always value in a woman's portrait, however much the forms may alter; in a certain sense, his portrait of Dr. Rive may be described as powerful; while his portraits of children are also conceived in an interesting way.

Schwartze left his native Amsterdam as a child, with his parents, for Philadelphia, whence he returned to Europe in 1838, at the age of twenty-four, and spent six years at the Düsseldorf Academy under Schadow and Sohn. At the same time, he took private lessons from Lessing, the well-known landscape-painter. In 1846, he settled in Amsterdam, because he had made so great a success in that city with his first portrait. Here he began by painting The Prayer, Puritans at Divine Service and The Pilgrim Fathers, which was lost on the way to America, but which is known through Allebé's lithographic reproduction. He made a name with these subjects and people are said to have regretted that he was obliged to abandon this style in order to execute his many commissions for portraits. We prefer, however, to think that the many and great admirers of his portraits will have regretted this decree of fate as little as did the subsequent generation, for this is certain, that, in his later years, his reputation was exclusively that of a sensitive portrait-painter, capable occasionally of genius. His great merit lies in this that, although of German descent, he chose Rembrandt, whom he admired above all other Dutchmen, as his model from the start.

Schwartze died in 1874. His chief pupil was his talented daughter, Miss Thérèse Schwartze, so well-known as a portrait-painter to-day.

- ↑ Whereas we had only the Frisian painter Otto de Boer, who painted The Raising of Lazarus for the church at Woudsend (where he was born in 1797) and The Sermon on the Mount, his best work, for the church at Heerenveen and, who therefore, like the painters in Catholic countries, was not obliged to adopt a flabby sentimentality in order to flatter the taste of the pietistic Protestants. De Boer died in 1856.