Enquiry into Plants/Volume 1/Chapter 68

Which kinds of wood are easy and which hard to work. Of the core and its effects.

V. Some wood is easy to work, some difficult. Those woods which are soft are easy, and especially that of the lime; those are difficult which are hard and have many knots and a compact and twisted grain. The most difficult woods are those of aria (holm-oak) and oak, and the knotty parts of the fir and silver-fir. The softer part of any given tree is always better than the harder, since it is fleshier: and carpenters can thus at once mark the parts suitable for planks. Inferior iron tools can cut hard wood better than soft: for on soft wood tools lose their edge, as was said[1] in speaking of the lime, while hard woods[2] actually sharpen it: wherefore cobblers make their strops of wild pear.

Carpenters say that all woods have[3] a core, but that it is most plainly seen in the silver-fir, in which one can detect a sort of bark-like character in the rings. In olive box and such woods this is not so obvious; wherefore they say that box and olive[4] lack this tendency; for that these woods are less apt to 'draw' than any others. 'Drawing' is the closing in of the wood as the core is disturbed.[5] For since the core remains alive, it appears, for a long time, it is always removed from any article whatever made of this wood,[6] but especially from doors,[7] so that they may not warp[8]: and that is why the wood is split.[9]

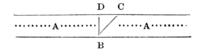

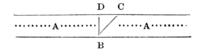

It might seem strange that in 'round'[10] timber the core does no harm and so is left undisturbed, while in wood whose texture has been interfered with,[11] unless it is taken out altogether, it causes disturbance and warping; it were rather to be expected that it would die[12] when exposed. Yet it is a fact that masts and yard-arms are useless, if it has been removed from the wood of which they are made. This is however an accidental exception, because the wood in question has several coats,[13] of which the strongest and also thinnest is the outermost, since this is the driest, while the other coats are strong and thin in proportion to their nearness to the outermost. If therefore the wood be split, the driest parts are necessarily stripped off. Whether however in the other case the object of removing the core is to secure dryness is matter for enquiry.[14] However, when the core 'draws,' it twists the wood, whether it has been split or sawn, if the sawing is improperly performed: the saw-cut should be made straight and not slant-wise. [15]Thus, if the core be represented by the line A, the cut must be made along the line BD, and not along the line BC: for in that case, they say, the core will be destroyed, while, if cut in the other way, it will live. For this reason men think that every wood has a core: for it is clear that those which do not seem to possess one nevertheless have it, as box nettle-tree kermes-oak: a proof of this is the fact that men make of these woods the pivots[16] of expensive doors, and accordingly[17] the headcraftsmen specify that wood with a core shall not[18] be used. This is also a proof that any core 'draws,' even those of the hardest woods, which some call the heart. In almost every wood, even in that of the silver-fir, the core is the hardest part,[19] and the part which has the least fibrous texture:—it is least fibrous because the fibres are far apart and there is a good deal of fleshy matter between them, while it is the hardest part because the fibres and the fleshy substance are the hardest parts. Wherefore the headcraftsmen specify that the core and the parts next it are to be removed, that they may secure the closest and softest part of the wood.

Timber is either 'cleft,' 'hewn,' or 'round': it is called 'cleft,' when in making division they saw it down the middle, 'hewn' when they hew off[20] the outer parts, while 'round' clearly signifies wood which has not been touched at all. Of these, 'cleft' wood[21] is not at all liable to split, because the core when exposed dries and dies: but 'hewn' and 'round' wood are apt to split, and especially 'round' wood, because the core is included in it: no kind of timber indeed is altogether incapable of splitting. The wood of the nettle-tree and other kinds which are used for making pivots for doors are smeared[22] with cow-dung to prevent their splitting: the object being that the moisture due to the core may be gradually dried up[23] and evaporated. Such are the natural properties of the core.

- ↑ 5. 3. 3.

- ↑ τὰ σκληρὰ conj. Sch. from G (?); ταῦτα P2 Ald. H.

- ↑ ἔχειν conj. Sch.; ἔχει ᾗ Ald. H.

- ↑ ἐλάαν conj. Scal. from G; ἐλάτην Ald. H.

- ↑ i.e. and this happens less in woods which have little core.

- ↑ ἅμα (? = ὁμοίως) MSS.; αὐτὴν conj. W.

- ↑ θυρωμάτων conj. Sch.; γυρωμάτων Ald. cf. 4. 1. 2; Plin. 16. 225, abietem valvarum paginis aptissimam.

- ↑ ἀστραβῆ ᾖ conj. Dalec.; ἀστραβῆ UMV Ald.

- ↑ i.e. to extract the core.

- ↑ See below, § 5.

- ↑ παρακινηθεῖσι, i.e. by splitting or sawing. πελεκηθεῖσι conj. W.

- ↑ And so cause no trouble.

- ↑ cf. 5. 1. 6. πλείους conj. Sch. from G; ἄλλους Ald. H.

- ↑ Text probably defective; ? insert ἐξῃρέθη after ξηρὸν.

- ↑ The figure would seem to be

- ↑ cf. 5. 3. 5. στρόφιγξ here at least probably means 'pivot and socket.'

- ↑ οὕτως Ald. H.; αὐτοὺς conj. W.

- ↑ μὴ add. W.

- ↑ ξύλον σκληροτάτη conj. Sch. from G; ξύλον σκληρότατον UMV: so Ald. omitting καὶ.

- ↑ ἀποπελεκῶσι conj. Sch.; ἀποπλέκῶσι UM; ἀποπλέκονσι Ald.; ἀποπελέκονσι m Bas.

- ↑ cf. C.P. 5. 17. 2.

- ↑ περιπλάττονσι conj. Sch. from G; περιπάττουνσιν Ald. H. Plin. 16. 222.

- ↑ ἀναξηρανθῇ conj. Sch.; ἀναξηραίνῃ Ald. H.