Hoyle's Games Modernized/Billiards

BILLIARDS.

The best introduction to an account of Billiards will be a brief explanation of the implements of the game and the terms used in connection with it.

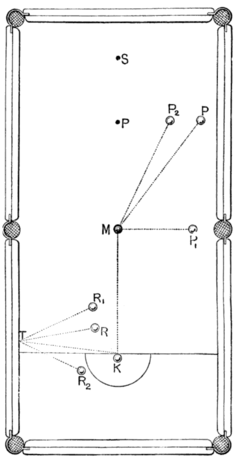

The bed of a full-sized table (see Fig. 1) is 12 ft. long, and 6 ft. 1½ inches wide. The pockets are 3⅝ inches across. The billiard spot, S, is 12¾ inches from the centre of the top cushion, opposite to the baulk. The pyramid spot, P, is placed at the intersection of two lines drawn from the two middle pockets to the opposite top pockets. The centre spot, M, is exactly between the middle pockets. The "baulk" is the space behind a line drawn across the table, 29 inches from the face of the bottom cushion, and parallel to it. The "half-circle," or "D," is 23 inches in diameter, its centre, K, coinciding with the centre of the baulk-line.

The game is played with three balls of equal size and weight, one red, one white, and one spot-white. The diameter of a ball must be not less than 21⁄16 inches, nor more than 23⁄32 inches. The diameter of a match ball, under National Rules, is 25⁄64 inches.

Fig. 1.

The choice of balls and order of play is, unless mutually agreed upon, determined by "stringing" (i.e., playing from baulk up the table, so as to strike the top cushion). The striker whose ball stops nearest the lower cushion may take which ball he likes, and play, or direct his opponent to play, as he may deem expedient. In stringing, under National Rules, the players must both play at the same time.

The red ball is, at the opening of every game, placed on the billiard spot, and must be replaced after being pocketed or forced off the table. If the billiard spot be occupied, the red ball must be placed on the pyramid spot, or, if that also be occupied, on the centre spot.

When any player plays from baulk, he must place his ball within the half-circle, or on the line that contains it.

Whoever breaks the balls (i.e., leads off) must play out of baulk, though it is not necessary that he shall strike the red ball, and he may give a miss in or out of baulk. But, if in baulk, he must first strike a cushion out of baulk. No player who is in hand is allowed to strike any ball in baulk, or on the baulk-line, unless his ball has first struck a cushion out of baulk. Should, however, a ball be out of baulk, the player in hand may strike any part of that ball without his own ball necessarily going out of baulk.

The player continues to play until he ceases to score, when his opponent follows on.

The various strokes are as under:

1.—A winning hazard is made by the player causing his own ball to hit an object ball and forcing the latter into a pocket.

2.—A losing hazard is made by the player causing his own ball to hit an object ball and forcing his own ball into a pocket.

3.—A cannon is made by causing the player's ball to strike the two object balls. By Billiard Association rules, when two object balls are struck simultaneously, the stroke shall be scored as if the white had been struck first. Under National Rules, such a stroke counts as if the red were struck first.

4.—A coup is made by forcing the player's own ball into a pocket without first striking another ball.

A miss counts one, a coup three, to the opposite player.

The scores are counted as follows:—

A.—A two stroke is made by pocketing an opponent's ball—i.e., a winning hazard; or by pocketing the striker's ball off his opponent's—i.e., a losing hazard; or by making a cannon.

B.—A three stroke is made by pocketing the red ball—i.e., a red winning hazard; or by pocketing the striker's ball off the red—i.e., a red losing hazard.

C.—A four stroke may be made by pocketing the white and spot-white balls; or by making a cannon and pocketing an opponent's ball; or by making a cannon and pocketing the striker's ball, the opponent's ball having been first hit.

D.—A five stroke may be made by scoring a cannon and pocketing the red ball; or by a cannon and pocketing the striker's ball, after having struck the red ball first or both balls simultaneously; or by pocketing the red ball and the opponent's ball without cannoning, or by making a losing hazard off the white and pocketing the red ball.

E.—A six stroke is made by the red ball being struck first, and the striker's and the red ball pocketed; or by a cannon off an opponent's ball on to the red and pocketing the two white balls.

F.—A seven stroke is made by striking an opponent's ball first, pocketing it, making a cannon, and pocketing the red also; or by making a cannon and pocketing the red and an opponent's ball; or by playing at an opponent's ball first and pocketing all the balls without making a cannon; or by playing at the red first, cannoning, and pocketing your own and the opponent's ball.

G.—An eight stroke is made by striking the red ball first, pocketing it, making a cannon, and pocketing the striker's ball; or by hitting the red first and pocketing all the balls without making a cannon.

H.—A nine stroke is made by striking an opponent's ball first, making a cannon, and pocketing all the balls.

I.—A ten stroke is made by striking the red ball first, making a cannon, and pocketing all the balls.

Reverting to the terms used in the game, the "cue" is the stick with which the player strikes the ball. It varies in length from 4 ft. 6 inches to 5 ft. The thick end or butt has a diameter of about 1½ inches. The small end or tip varies from ½ to ¼ inch in diameter. The average is about ⅜ of an inch.

The tip is formed of two pieces of leather glued together. When the tip gets greasy or too smooth, it should be rubbed with a piece of chalk.

The Rest.—The real "rest," that is, the support on which the cue is raised in order to strike the ball, is the left hand. This, however, is more generally termed the "bridge"; what is known as the "rest," or "jigger," is a cross of wood fixed at right angles to a handle about the same length as the cue, in order to enable a player to strike a ball when it is too far away to allow him to use his hand as a bridge. Special rests, and cues of extra length, are made to meet exceptional positions of the balls.

In Hand.—A ball is said to be in hand when it is off the table, and the player has to play from the half-circle or D.

Breaking the Balls.—Whoever plays, being in hand, when the red ball is on the spot and the other ball also is in hand, is said to break the balls.

In Baulk.—A ball is said to be in baulk when it is between the baulk-line and the bottom cushion.

Break.—The series of scores terminating with the stroke in which the player fails to score is called a break.

Screw and Screw-back.—This is putting a rotatory motion on a ball, causing it to spin on a horizontal axis backwards. Screw is put on by striking the ball below the centre.

Following Stroke.—This is putting a rotatory motion on a ball, causing it to spin on a horizontal axis forwards instead of backwards. The stroke is made by striking the ball high up above the centre.

Side.—This is a rotatory motion put on a ball, making it spin on a perpendicular axis.

In each of the foregoing cases the ball is made to take, after striking another ball, or a cushion, a direction different from that which it would take did no such rotatory motion exist.

In order that the learner may the better understand the meaning of screw, screw-back, following stroke, and side, we will illustrate them by means of a diagram.

In Fig. 1 we will suppose the red ball to be placed on the middle spot in the table, M. The player places his own ball in the centre spot in the baulk-line, K, and aims his ball, first of all, so as to strike the object ball with the ordinary Half-ball Stroke—that is, the centre of his ball advances towards the extreme edge of the object ball.

In Fig. 2, O is the object ball; S, the striker's ball. In order to play the half-ball stroke, it is necessary that the player should aim at the point E, the extreme edge of the horizontal diameter of the object ball. Of course, as the diagram shows, he will not strike the ball in the point at which he aims (this is never done save in the case of the ball being struck exactly in the centre), but as S1, in the point C. When the object ball is thus struck, the striker's ball, supposing there is no screw on the ball, will take the direction indicated in Fig. 2 as S2. This angle is called the natural angle; about this natural angle we shall have to say more by-and-by. Suppose the stroke played thus. After playing, the ball will follow the line M P (Fig. 1). Now suppose some strong screw had been put on the ball by hitting it low down. The ball, owing to the hit, and to its after-contact with the ball at M, would follow the line M P; but, owing to the rotatory motion making the ball revolve or spin backwards, it has a tendency to run back again towards K, the point from which it started. Under the influence of these two forces, the ball takes the medium course shown by the dotted line M P1. In other words, the striker, although he hits the object ball a half-ball stroke, screws into the middle pocket.

Fig. 2.

Now suppose, instead of hitting the ball below the centre, he hits it high up above the centre, so as to make the ball rotate forwards. After the balls have come in contact, the rotatory motion forwards has a tendency to make the striker's ball run onwards towards the top cushion and away from K, the point from which it started; but the contact with the object ball would—did no rotatory motion exist—cause it to follow the direction of the line M P. Under the influence of these two forces the ball takes a medium course, and follows the line M P2.

If the player hit the ball at M full, that is, played at it quite straight and hit the ball at M in its nearest point, then, if he put on screw, his own ball would, after striking the ball at M, stop and run back towards K, fast or not according to the amount of rotatory motion he succeeded in putting on his own ball when he struck it.

If the player hit the ball at M full, and hit his own ball high up and above the centre—the following stroke—his ball, after striking the ball at M, would follow on, and, if he hit it exactly, would go on in the direction of the spots, P and S.

In putting on side, the ball is caused to rotate on a perpendicular axis. For instance (vide Fig. 1), suppose the player places his ball on the centre spot in baulk, K, and hits the cushion in the point T without putting on any side, then the ball would rebound in the direction of T R, just as the angles of incidence and reflection are equal. Suppose, however, the player strikes his ball on the right-hand side, causing it to rotate on a perpendicular axis. When the ball touches the cushion at T, this rotation, owing to the friction between the ball and the cushion, causes the ball to take the direction shown in the diagram by the line T R1. If, on the other hand, the player hits his ball on the left-hand side, the ball will rebound in the contrary direction shown by line T R2. This latter stroke is what every player has to make when he wishes to give a miss in baulk.

When a great deal of side is put on a ball, this side has but little effect till the ball touches a cushion.

Fluke.—When a player plays for one thing, misses it, and gets another, the stroke is called a fluke. Thus, if a man plays for a cannon, misses the cannon and his ball runs into a pocket off the other ball instead, it is a fluke. If, however, he plays for the cannon and makes it, and then his ball runs into a pocket, it is not regarded as a fluke, although he gets what he did not play for.

A Jenny is a losing hazard into one of the middle pockets off a ball near to one of the lower-side cushions. A long jenny is a losing hazard off a ball similarly placed into one of the top pockets.

Spot Stroke.—A stroke by which a player pockets the red ball from the billiard spot, at the same time bringing his own ball into position to pocket the red again, when the latter is replaced on the billiard spot.

All-in Game.—A game in which, by prior agreement, any number of spot strokes may be consecutively scored.

Spot-barred Game.—By the Billiard Association Rules, "if the red ball be pocketed from the billiard spot twice in consecutive strokes by the same player, and not in conjunction with any other score, it shall be placed on the centre spot; if a ball prevent this, then on the pyramid spot, and if both centre and pyramid spots be covered, then on the billiard spot. When the red ball is again pocketed it shall be placed on the billiard spot."

Furthermore, "if when the billiard spot is occupied, a player pocket the red ball from the pyramid spot twice in consecutive strokes, and not in conjunction with any other score, it shall be placed on the centre spot. Should the player, with his next stroke, pocket it again, it shall be placed on the pyramid spot."

To get on the Spot.—When a player gets his own ball into an easy position for playing the spot stroke, he is said to get "on the spot."

Kiss.—When the balls come in contact a second time they are said to kiss.

A Nursery.—A series of cannons made when all three balls are very close together is called a nursery of cannons.

Safety.—When any one plays simply to leave the balls in such a position that his opponent cannot score by his next stroke, he is said to play for safety.

Twist.—Another name for screw.

Stab, or Stick-shot.—When any one plays to put a ball in and leave his own ball exactly on the spot where the object ball was, or only a very little way beyond it, the stroke is called a stab.

Line Ball.—A ball whose centre is exactly on the baulk-line.

Foul.—A stroke which infringes any rule of the game.

Object Ball.—The ball upon which the striker's own ball impinges.

Jammed.—When the two object balls touch in the jaws of a pocket, and each touches a different cushion at the same time.

Steeplechase Stroke.—When the striker's own ball is forced off the surface of the table on to, or over, one or both of the object balls. By the Billiard Association Rules, this stroke, "if properly made, is fair, and the referee is the proper person to decide the matter."

One of the most important points for the beginner, as well as for the more experienced player, is the selection of a thoroughly good and reliable cue. Strangely enough, this matter generally receives very little attention, the neophyte being content to take the first that comes to hand. What is even worse, he will change about from day to day,—or from hour to hour,—using cues of different shapes, weight, and balance; and is then surprised that he does not make the progress that he expected.

Reverting to the subject of the half-ball stroke, it is of the greatest importance that all beginners should understand how much depends upon their being able to hit the object ball in the way shown in Fig. 2. Their whole future success as billiard-players will depend upon the accuracy with which they learn to hit the object ball in this particular manner.

First of all, the beginner must learn to hit his own ball freely. We would recommend him to take his first practice-lesson by learning simply how to hit a ball hard—i.e., have only one ball to play with. After he has gained a certain amount of what is called freedom of cue, he must next learn to aim at the object ball, so that he always hits it in what we have described as the half-stroke. To ascertain whether he has acquired sufficient "freedom of cue," let him see how many times he can send his own ball up and down the table.

In learning to simply strike your own ball, it is important to learn to strike it hard without putting on side. Place your ball in baulk, say nearly in the centre of the half-circle; now play straight up at the top cushion hard. If you hit your ball fairly in the centre, the ball will come back straight; if you don't you will put on side, and you can tell how much by the angle at which the ball will rebound from the top cushion. Commence learning, therefore, by hitting your own ball hard enough to send it four to five times up and down the table without side. This is not so easy as many persons would think.

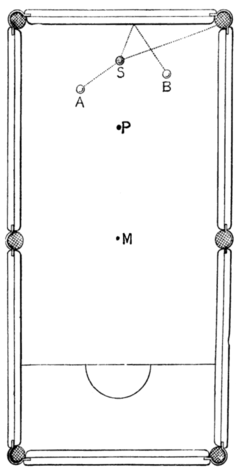

Having learnt to hit his own ball fairly in the centre, the beginner must next learn to hit the object ball a half-ball stroke; and for this purpose it is a very good exercise, at the commencement, to place the red ball on the spot, S (vide Fig. 3), and the striker's ball in position A, that is, just in front of the middle pocket, an inch or two along an imaginary line drawn from the centre of the middle pocket to the edge of the object ball placed on the spot.

The losing hazard off the red into the right-hand top pocket ought now to be a certainty, it being a simple half-ball stroke. After making the hazard, the red ball should, after striking the top cushion, rebound in a line right down the centre of the table (as shown by the dotted line W W).

By watching the direction of the red ball after striking, the beginner will be able to see if he has struck the ball correctly. If he hits it too fine, the red ball will come down the table on the left of the centre line, W W. Should he strike the red ball too full, the red will come down the table on the right-hand side of the line W W.

When the beginner has practised this stroke till he can make a certainty of it, he may then begin to learn how to play what may be called "forcing hazards." For this purpose he can gradually place his own ball lower and lower down the table, as shown in Fig. 3. Suppose, for instance, he places his own ball at B. There is still an easy losing hazard off the red into the top corner pocket, the only difference being that the stroke must be played harder. When the ball was placed at A, the losing hazard could be made by simply what is called dropping on to the ball. In fact, the stroke could be played so slowly, that the red ball, after striking the top cushion, would not rebound more than a foot down the table. As, however, the striker's ball is placed lower and lower down the table in the positions shown by the letters B and C, so the stroke must be played harder and harder.

Another perfect half-ball stroke that can be played either slowly or fast, is shown by the two lines, in Fig. 3, drawn from the spot S to the two top pockets. Suppose a ball to be placed in the centre of either top pocket, or a few inches along the line drawn from the pocket to the spot. Then it is a simple half-ball stroke to go in off the red into the other top pocket.

Place the white ball an inch or two away from the top pocket along the line drawn, and place the red ball on the spot. Then drop on to the ball quietly. The hazard is easy, and, supposing you play from, say, the left-hand top pocket, you will not only make the losing hazard, but you will leave the red ball in a position for another easy hazard into the middle pocket. Your own ball, the white, for the next stroke will be in baulk; the red ball will, if you play the stroke correctly, travel along the dotted line shown in the diagram, and stop somewhere about R, thus leaving an easy hazard next time into the right-hand middle pocket.

Fig. 3.

Having thus practised the half-ball stroke with slow strength and fast strength, the next point to be considered is losing hazards into the top pockets from baulk. These losing hazards may be called the very backbone of the game.

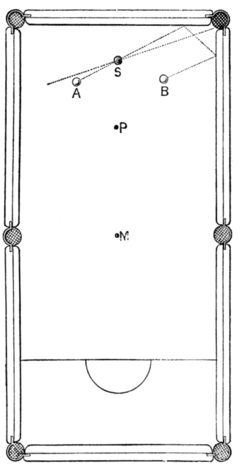

The chief difficulty experienced by a beginner will be to know where to spot his ball in baulk. This will only come with practice. The eye will gradually accustom itself to the angle. A good player can tell at a glance whether or not a stroke is easy. We would recommend any one learning the game to make one or two spots on the table as follows. First place a card or thin piece of wood upright against the top cushion, and then measure down the table 3 ft. 9½ in. Make a mark on the cloth (a little cross is best), and then place the red ball on this spot. Next let him place the white ball at K (Fig. 4), the centre spot in baulk. The red ball is placed on the spot A, which, as we have said, is just 3 ft. 9½ in. from the face of the top cushion. Now there is an easy losing hazard, if the stroke be played with the ordinary half-ball stroke, into either top pocket off the red ball.

This stroke is capital practice for the beginner, as it gets his eye used to the angle which we have called the "natural" angle.

The advantage of playing the natural angle is that, supposing you fail to hit the ball exactly as you intended, a very slight error in aiming does not alter materially the direction of your own ball after it has come in contact with the object ball.

Fig. 4.

Suppose, now, the beginner has succeeded in going into first one top pocket and then the other several times, let him take the red ball off the spot marked A in Fig. 4, and place it on M, the centre spot in the table. Now let him place his own ball in baulk on the proper spot to go into, say, the left-hand top pocket off M. The proper spot is B in the diagram, but then, where is B? B ought to be seven and a half inches from K, the centre spot in baulk. Similarly, if the player wished to go into the right-hand top pocket off the red ball at M, he would have to spot his own ball on a spot seven-and-a-half inches to the right of K.

As a rule, beginners all make the same mistake. They will, as a rule, spot their ball too near to K, and, of course, the further they are out in their reckoning, the more they have to learn. It would be as well, however, to let a beginner play the stroke. Suppose, for instance, that instead of spotting his ball at B, seven and a half inches to the left of K, he spots his ball only five inches to the left of K. Let him play his stroke, and instead of going into the left-hand top pocket, his ball will strike the left-hand upper cushion several inches below the pocket. Now let him measure the correct seven and a half inches, and, although he will think he is going to miss the stroke, to his own surprise he will make it. It is very good practice to go in off a ball placed on the middle spot M, first into one top pocket, and then into another, being careful always to watch the direction taken by the red ball after the stroke, with an eye to playing the right strength to leave an easy losing hazard next time.

We next come to—

Middle-Pocket Hazards.

We will suppose that the beginner has now fairly learned how to play losing hazards in the top pockets, and also how to spot his ball for the natural angle. In playing losing hazards into the middle pockets, it is quite as important that this angle, and this only, should be used. In Fig. 5 we give two illustrations of simple hazards into the middle pockets. The hazards themselves are, comparatively speaking, easy; but the chief point to be borne in mind is position—that is, having made the hazard, how can we leave the red ball so that there shall be another easy hazard next time? The endeavour should be to keep the red ball in the centre of the table as much as possible. As a rule, the game is to play to bring down the red ball over the middle pocket again. Now, in Fig. 5, suppose the player at H tries to go into the right-hand middle pocket off a ball at D, the proper play would be to strike the red ball so that it goes up the table, and, following the dotted lines, returns to D1. If the player hits the red a trifle too fine the red ball would travel to the left of this dotted line, and a losing hazard would be left off the red into one of the top pockets. If, however, in playing the stroke, the player hits his ball a trifle too full, the red ball would then probably travel along the dotted line terminating in D2, and there would be no score left next time.

Fig. 5.

A similar stroke is shown in the left-hand middle pocket. The striker spots his ball at B, and goes into the middle pocket off a ball at A. The endeavour should be to send the red ball up the table in the direction shown by the dotted line A C.

If the red is sent up the table to the left of this line, unless very accurate strength is played, there will be probably no score left next time. If, however, the player is careful not to hit the ball at A too full, the ball will travel rather to the right of the line A C, and then, being in the middle of the table, if the strength is insufficient to bring the ball over the middle pocket, there will still be a losing hazard left into one of the top pockets. This is the chief point to be considered in making losing hazards in the middle pockets, and naturally introduces that all-important subject for consideration in learning to play Billiards, viz.—

Position.

There are thousands of men who have played Billiards all their lives, but are still very poor players, because in learning to play they never studied position. They play simply for the stroke, and never give a thought to what will happen in the next stroke. If you watch a first-class player make a break, you will probably see him make a long series of very easy strokes, any one of which you yourself could have made with the greatest ease. The one difference, in fact, between your play and his would have been this—that you would make the easy stroke, and fail to leave another easy stroke next time, whereas he would not fail; hence his break—a series of easy strokes; hence your break—one easy stroke, and a breakdown.

Space will not allow us to give a long series of diagrams, explaining the various ways of playing for position, but we will indicate a few general principles. First—

Losing Hazards.

In playing for any losing hazard, it should be remembered that the position of one ball after the stroke is fixed: the striker's own ball will be "in hand." Hence, he has only to consider the position of the object ball, which we will suppose to be the red. Now, the object of the player is to leave an easy stroke next time. As a rule, the red ball must be hit in a certain spot to ensure the hazard, the only exception being when the red ball is close to the pocket, and the player's ball close to the red. In this latter case it is often the best plan to just touch or graze the red ball so as hardly to move it, and—supposing, of course, it is not one of the bottom pockets—to leave the red ball over the pocket where it is. If, however, you are some way off the red ball, you will have to hit it in one place in order to make certain of the hazard. Consequently, position will simply depend upon strength. It is as well to remember that if a ball is left anywhere near the middle of the table, there is always an easy hazard left next time.

No player can leave a ball on a certain spot exactly. The greatest expert cannot do more than leave it "there or thereabouts." In fact, very often, in playing a losing hazard, all we have to do is not so much to play where to leave the red, but where not to leave the red.

Sometimes it may be the best play to try and leave the red ball close to the white ball, so that the next stroke will be an easy cannon. As a rule, however, the best play is to leave the red ball over a pocket, so that you can go in off it again next time. All the best "all-round" breaks are made by a series of losing hazards with occasional cannons. It is in playing cannons that the chief difficulty arises in getting position, but before we discuss cannons, a few words about—

Winning Hazards.

It is evident that after playing a winning hazard the position of the object ball is known—viz., as a rule, on the spot. Should the player put in the white, his only excuse must be to make a baulk; otherwise it is bad play. His opponent, next time he plays, can spot his ball anywhere he likes in the semicircle, and if the other balls are out of baulk, he is almost certain to score. Consequently, the only winning hazards worth discussing are red winning hazards. In making a winning hazard, the player, as a rule, should try and get near the spot himself, so as to play for the spot, or else play to leave his own ball where there would be an easy losing hazard off the red on the spot next time. In Fig. 6 we give two illustrations. Suppose, first of all, the red ball is over the right-hand middle pocket at H. The proper professional play would be to put the ball in the pocket, and then run up the table towards L, and try and get into position for the spot, but the ordinary amateur, who, when he gets into position for the spot, can only make one hazard and then breaks down, had better not play for the spot at all. In the position given in the diagram, it would be better play to put the red ball in the pocket, and try and leave your own ball at H1; then there is a certain losing hazard next time off the red into the left-hand top pocket.

Fig. 6.

Again, suppose the balls are left in the position W (the white ball), and X (the red ball), many beginners would play for the six stroke, but it would be very bad play, as the red ball would be on the spot, and the striker in hand. The proper play is to put the red ball in the pocket and leave your own ball in the jaws of the pocket, thus leaving a certain losing hazard—in off the red into the opposite top pocket—next time; a stroke, too, in which it is always easy to leave the red ball over the middle pocket in the stroke following.

However, as we have said, the chief difficulty in getting good position is when playing—

Cannons.

Here the player has to consider the position of all three balls at the end of the stroke. There are two ways of getting position in playing a cannon. We can leave the red over a pocket, or play to bring the balls together. It is obvious that when all the balls are close together, it is almost a certainty that there is an easy score left.

Suppose, in Fig. 6, the red ball is on the spot S, the white ball at B, and the player in hand. There is, of course, an easy cannon left, but how ought he to play it so as to leave an easy score next time?

The game here is to leave the balls together at the end of the stroke. The striker spots his ball at A in baulk, so as to strike B the ordinary half-ball stroke. The stroke should be played slowly, so that the white ball rebounds off the left-hand upper side cushion at C, and travels towards D. The player's own ball hits the red gently, and all three balls are left close together, near the top of the table, one of the best positions possible.

Fig. 7.

|

Fig. 8. |

In playing to leave the red ball over a pocket, a good deal depends upon whether you play a cannon off the red on to the white, or off the white on to the red. For instance, in Fig. 7, suppose the striker in hand, and the two other balls stationed at A and R. If A is the red ball, the stroke is played one way, and if A is the white ball it is played another way. If A is the red you should play to make the cannon with just sufficient strength to double the red across the table, and leave it in position A1, over the middle pocket. If R was the red ball, you ought to play with just sufficient strength, and also sufficiently accurately, to hit the red ball full and leave it in position R1, over the left-hand top pocket.

Another important point in playing cannons is to play what is called "outside" the balls when they are close together. Suppose, in Fig. 7, the balls are in the position shown in C, D, and E. C is the player's ball. If he hits D and makes the cannon hitting E full, he separates the balls, but if he plays so as to just touch D and E, hitting them on the extreme edge, he keeps them together.

Fig. 9.

|

Fig. 10. |

We will, in conclusion, give a brief explanation of the spot stroke in the "all-in game." This is in fact, as we have already seen, a series of spot hazards.[70] We must, however, warn the beginner that though nothing looks more simple, nothing really is more difficult. The simplest position for the spot stroke is when the striker's ball is in a direct line with the red ball and the pocket (Fig. 8). Of course, the proper play is to screw back and bring your own ball into the same place. Were this a "certainty," the striker would go on scoring for ever. Sooner or later, however, he will find his ball will not come back quite straight. It will come back slightly nearer the top cushion, or rather more away from it. In the first of these cases (position 2, Fig. 9), the best plan is to follow through the red ball. This can be done simply by a following stroke. A is the striker's ball; B the position of the striker's ball after the stroke. When the balls are nearly, but not quite straight, this is done by means of a stab shot.

In position 3 (Fig. 10) the striker's ball is at A. The play now is to drop on to the red ball with sufficient strength to put it in, and get position at B off the top cushion. Sometimes a little side is necessary.

In position 4 (Fig. 11) the striker's ball A is nearly, but not quite, in a line with the red ball and the opposite pocket. When this is the case, the only way to get position is to run through the red and get position off the two cushions. You must play to hit your ball very high and with a great deal of freedom of cue. It is a stroke in which a beginner would probably fail.

Fig. 11.

|

Fig. 12. |

It is as well to know within what limits the spot stroke can be played. Suppose we draw a line, X Y (Fig. 12), through the spot S, parallel with the top cushion. If the striker's ball is within this line or nearer to the top cushion, it is no use putting in the red gently, as position would be lost. The only plan to recover position is to play all round the table. Suppose the striker's ball is within the line at A, he now plays to put the red ball in the right-hand top pocket and recover position by going right round the table till his ball stops at B. This is a very difficult stroke, but is often played for and obtained by a first-class player.

THE BILLIARDS CONTROL CLUB RULES.

These Rules (issued in February, 1909) are specially applicable to professional matches, and,—like the Rimington-Wilson Code, on which they are based,—have particularly in view the reduction of safety misses to a minimum and the imposition of one definite penalty for each and every kind of foul stroke or illegitimate miss. In issuing the Code, the Secretary lays stress on the following provisions:—

A player may not make two misses in successive innings, unless he or the opponent scores after the first miss, or a double baulk intervenes. (Rule 9.)

When striker's ball remains touching another ball, red ball shall be spotted, and non-striker's ball, if on the table, shall be placed on the centre spot; striker shall play from the D; if non-striker's ball is in hand, red shall be spotted, and striker shall break the balls. (Rule 10.)

Consecutive ball-to-ball cannons are limited to 25; on the completion of this number the break shall only be continued by the intervention of a hazard or indirect cannon. (Rule 13.)

Penalties.

If, after contact with another ball, striker's or any other ball is forced off the table, the non-striker shall add two points to his score. (Rule 18.)

For a foul stroke the striker cannot score, and his opponent plays from hand. His ball shall be placed on the centre spot, the red ball shall be spotted, and his opponent shall play from the D.

For refusing to continue the game when called upon by the referee or marker to do so, or for conduct which, in the opinion of the referee or marker, is wilfully or persistently unfair, a player shall lose the game. (Rule 18.)

PYRAMIDS.

This game is played by two persons with sixteen balls,—one white, and fifteen red. The latter are arranged in the form of a solid triangle, with its apex on the Pyramid spot (P in Fig. 1), and its base towards the top cushion and lying parallel thereto.

At the commencement of the game, one player leads off from the half-circle, and plays at any one of the red balls. Should he pocket one or more balls, he scores one for each red ball pocketed. He continues playing till he fails to score.

If a player gives a miss, or pockets the white ball, a point is taken off his score and he must replace one of the red balls he has previously pocketed; on the Pyramid spot, if unoccupied, or, if that be occupied, as near to it as possible in a line directly behind it. If he has not previously pocketed a ball, he owes one, and must pay it by replacing the first ball that he pockets later on.

After a miss, the opponent follows on from where the white ball stopped; but after a pocketing of the white ball, the opponent follows on from the half-circle. In playing at a red ball, baulk is no obstacle.

If a striker pockets the white ball, and at the same time pockets one or more of the red balls, he gains nothing by the stroke, but one is deducted from his score; the red balls pocketed must be spotted on the table, as well as one of the striker's red balls previously pocketed. The opponent follows on from the half-circle.

When the red balls have all been pocketed but one, the player making the last score continues playing with the white ball, and his opponent uses the other. If a striker now make a miss, or pocket the ball he is playing with, the opponent adds one to his score, and the game is over.

SHELL OUT.

This is a name given to Pyramids when played by more than two persons.

When a striker pockets a red ball he receives from each of the other players a stake previously agreed on. No ball is ever replaced on the table after a miss, or after pocketing the white. Should any player miss or pocket the white, he pays for each of the other players as well as for himself whenever the next red ball is pocketed. When only one red ball is left in play, each player continues playing with the white. Pocketing the red is now paid double all round; and if a striker miss, or pocket the white, he pays double all round.

The order of play is drawn for at the beginning of each game.

Works of Reference.

- Billiards Expounded. By J. P. Mannock, assisted by S. A. Mussabini. Grant Richards, 2 vols., 15s.

- Practical Billiards. By C. Dawson. To be had from the author, "Thorns," Hook Road, Surbiton, Surrey. 12s. 6d.

- Hints on Billiards. By J. Buchanan. Geo. Bell and Sons.

- Modern Billiards. By J. Roberts. C. Arthur Pearson, Limited.

- Billiards for Everybody (Oval Series). By Charles Roberts. Routledge. 1s.

- Billiards. By Joseph Bennett. Edited by Cavendish. De la Rue and Co. 10s. 6d.

- Billiards (Badminton Library). By Major W. Broadfoot, R.E., and others. Longmans. 10s. 6d.

- Pyramids and Pool (Oval Series). By J. Buchanan. Routledge. 1s.