Interregional Highways/Locating the interregional routes in urban areas

LOCATING THE INTERREGIONAL ROUTES IN URBAN AREAS

The location of interregional highways to serve the city as it is today, no matter what its condition may be, is a comparatively simple task.

Once constructed, however, the interregional highways would be relatively permanent. But cities cannot be said to have attained well organized and relatively permanent form.

Because of these two things—the permanency of the highways and the more or less planless form of the cities—the interregional routes must be so located as to conform to the future shape of the cities, insofar as this can be foreseen, as well as to the existing pattern of urban centers.

American cities of today are surprisingly uniform in their status and condition, although no generalized description can ever adequately portray any one of them. The focal point of them all, however, is the central business district, which contains the large stores and office buildings and is often the cultural and civic center of the urban community. But this “downtown area” is cramped, crowded, and depreciated. Land values are often less than they were 20 years ago.

This center shades off into a secondary business area which merges almost imperceptibly with a large area of mixed land uses and run-down buildings. This is the slum area where living conditions are poor.

Around the slums is an even larger area of residential property in various stages of depreciation. This is the widely discussed “blighted area.” Without the application of effective rehabilitation measures, it will become part of the city’s slums.

Beyond this blighted area lie the newer residential areas. They extend far out beyond the city limits, in the form of widely scattered subdivisions, merging almost imperceptibly into the farm lands.

Interlaced through all of these sections are inadequate highways and streets, and railroads extending into the heart of the city. Along the railroads the city’s industrial plants are located. The newer ones, such as the large war industries, are often found far out in the environs.

While every city contains some admirable features and thoroughly satisfactory parts, rapid expansion and virtual transformation in recent years have produced an unbalanced condition fraught with great economic difficulties. Few cities have managed to grapple successfully with the situation. In nearly all cities great efforts are being made today to restrain excessive decentralization, and to rehabilitate slum and blighted areas.

The plight of the cities is due to the most rapid urbanization ever known, without sufficient plan or control. The result is square mile after square mile of developed city that is functionally and structurally obsolete both as to buildings and neighborhood arrangements.

The automobile has made partial escape from this undesirable state of affairs easy and pleasant for at least some of the population. Suburban home developments have been made attractive largely by the possibilities of quick and individual daily transportation thus afforded.

Suburban business centers have followed the clustering of suburban homes. The more recent growth of the parking problem with its attendant difficulties of retail trade in the central business section, has to a limited extent induced an outward movement of some large emporiums and a more numerous establishment of branch and chain stores in suburban communities.

Modern industrial processes, requiring more ground space than is available at permissible cost within the city, have been and will continue to be the cause of a preference for outer locations as industrial sites, and the most favorable locations are those best served by transportation facilities, including highways.

From the standpoint of the city, as a corporation, a serious effect of the outward movement of residence, business, and industry has been the depreciation in value of city-contained land and property available by taxation for the financial support of the city government and the various services it must supply to its residents.

And finally, another disadvantage, affecting important city interests, has been the increasing tendency toward the diversion of trade from established retail commercial concerns located in the central business district to enterprises newly founded in outer sections, often without the city boundaries.

What the city will be like in the future depends on whether its future development is planned or haphazard. Several new conditions, however, will greatly affect city development. One of the most important of these is that future population growth of cities will be limited. To base the planning of highways or anything else on expectations of urban population increases like those of the past, would seem to be unwise.

Twenty-five years ago there was virtually{no control of growth and city development through city planning. Today many cities have plan commissions and a city plan in some stage of development.

Urban planning is really just now coming to grips with one of the basic urban problems—decentralization or dissipation of the urban area to an extent not economically justified, This is a most difficult problem to solve. So long, however, as the central areas of the cities are poor places in which to live and rear children, people will continue to move to the outskirts. Undoubtedly a factor that has facilitated this movement has been the improvement of highways.

If for any city, maps are prepared representing in bold silhouette the areas of the city and its environs occupied by buildings at definite successive periods of its history, it is possible to obtain a clear idea of the manner of the city’s growth. The series of such maps for several cities (fig. 26) illustrate typical growth processes common to many cities.

One of the most striking revelations of these maps is the manner in which, in the more recent periods, the growth of the cities has been extended outward in slender fingers along the main highways entering the city. This is undoubtedly due to the improvement of the main highways, which has resulted in a relatively satisfactory connection of bordering areas with the city.

Between the outstretching fingers of development along the main highways, pronounced wedges of relatively undeveloped land appear in the maps for each of the recent periods. Attention will be called to these wedges of undeveloped land again later in this report.

The immediate inference from theese maps is that the creation of such ample and efficacious traffic facilities as the improvement of the interregional routes would supply, will exert a powerful force tending to shape the future development of the city.

It is highly important that this force be so applied as to promote a desirable urban development. If designed to do this, the new facilities will speed such a development and grow in usefulness with the passage of time. Unwise location of the interregional routes might not be sufficiently powerful to prevent a logical future city development, but would be powerful enough to retard or unreasonably distort such development. The interregional highways must be designed for long life. An unwise location would diminish their usefulness as time passes. Principles of Route Selection in Cities

While the selection of routes for inclusion in the interregional system within and in the vicinity of cities is properly a matter for local study and determination, the Committee suggests the following principles as guides for local action.

Connection with city approach routes.—Selection of interregional routes within and in the vicinity of a city should be made cooperatively by the State highway department and appropriate local planning and highway authorities and officials.

For the service of interregional traffic and other traffic bound in and out of the city to and from exterior points, the problem is one of convenient collection and delivery. The State highway department should have the primary responsibility of determining the detailed location of routes leading to the city, as it will have the essential knowledge of origins and destinations of the traffic moving on the adjacent rural sections of the routes.

Once the routes enter the environs of the city, however, they become a part of the sum total of urban transportation facilities, and as such must bear a proper relation in location and character to other parts of the street system. In addition to the traffic to and from exterior points, they will carry a heavy flow of intraurban movement of which city authorities will have knowledge or will be best able to measure or predict.

In some urban centers, cooperation between the State highway department and local authorities will be complicated by the fact that the metropolitan area will consist of several cities and perhaps one or more county jurisdictions and that decisions will need to be reached on a metropolitan rather than a city-by-city basis. Recognizing the difficulty of unifying a multiplicity of local agencies, the Committee believes that the creation of an over-all authority would be highly beneficial and desirable in complex urban areas. A metropolitan authority would avoid obvious mistakes in the location of the interregional routes and thus prevent distortions in the development of the area. Only through some over-all agency such as a metropolitan authority can there be developed an adequate thoroughfare plan to provide for all traffic needs. The interregional routes should be coordinated with the metropolitan street and highway plan. Such a metropolitan authority could anticipate and avoid obvious mistakes in the location of the interregional routes, prevent distortions based on short-sighted compromises, and in the long run lead to the best solution for all concerned.

Penetration of city.—Because of the traffic congestion encountered in passing through cities, it is the usual conclusion of those who make long automobile trips that they could save much time and avoid annoyance if so-called bypass routes were available to carry them around all cities. Comparative travel-time studies usually confirm this impression.

Such a study at Lafayette, Ind., for example, showed that the average time required to travel 6 miles through the city between two points on U.S. 52 was 14 minutes. To travel between the same two points over 6⅔ miles of existing roads around the city required an average of 9 minutes.

Another example is afforded by a recently constructed 9.5-mile route around Newport News, Va., from the James River Bridge to Fort Monroe. At 35 miles per hour this bypass can easily be traveled in 16 minutes. The old route through the city was 11.2 miles long and required & minimum of eight stops. Travel time in off-peak hours averaged 29 minutes and during rush hours was considerably longer. The new route, therefore, saves at least 13 minutes and avoids the necessity of frequent stops and starts.

But the common impression that provision of such routes would constitute invariably a complete, or even a substantially adequate, solution of the highway problem at cities is not well-founded. It is a fallacious conception of the need for adequate accommodation of the traffic moving over the rural highways. From the standpoint of the cities it fails as a solution of the most serious aspects of the problem.

The root of the fallacy, so far as the rural highways are concerned, lies in the fact that on main highways at the approaches to any city, especially the larger ones, a very large part of the traffic originates in or is destined to the city itself. It cannot be bypassed.

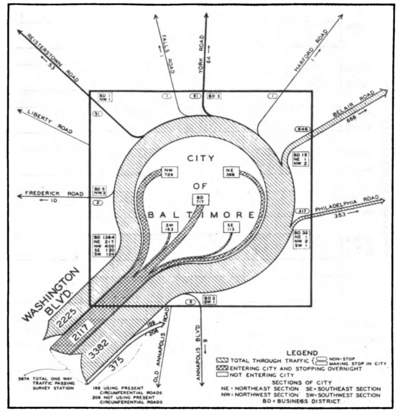

This fact was demonstrated by the Public Roads Administration in its report entitled “Toll Roads and Free Roads,” published in 1939,[1] by reference to studies of the origin and destination of traffic observed on U.S. 1 between Washington and Baltimore. A diagram presented in that report is here reproduced as figure 27. The text that accompanied it is as follows:

As shown by the topmost line in this graph, the total traffic on the route rises to a peak at each city line and drops to a trough between the two cities. Of this total traffic, that part above the highest of the horizontal lines represents movements of less length than the distance between the cities. At each city line this part consists of movements into and out of the city all of which are of shorter range than the distance to the neighboring city. The uniform vertical distance between the highest and the next lower horizontal lines measures the amount of traffic on the road moving between points in each city. The height of the next lower horizontal band represents the traffic moving between Washington and points beyond Baltimore; that of the next, the traffic moving between Baltimore and points beyond Washington; while the height of the lowest horizontal band measures the volume of the traffic moving between points that lie beyond both Baltimore and Washington. Of all the traffic shown as entering the two cities, only this last part plus that represented by one or the other of the next two higher bands can be counted as potentially bypassable around the two cities. At Washington this bypassable maximum is 2,269 of a total of 20,500 entering vehicles; at Baltimore it is 2,670 of a total of 18,900 vehicles. The remainder of the

An origin-destination study of the traffic on this same highway was made at an earlier date by Coverdale & Colpitts[2] at a point near Baltimore. It serves further to illustrate the manner in which the traffic approaching a large city by a typical main highway is distributed to the center and various quarters of the city and, via various other main routes, to points beyond the city.

Figure 28 is adapted from the report of this study. It shows that of a total of 5,874 vehicles approaching the city, 717 moved to the center of the city as their ultimate destination. Others, numbering 726, 398, 113, and 163, respectively, proceeded to ultimate destinations in the northwest, northeast, southeast, and southwest quarters of the city. A large number, 2,225 vehicles, went to points within the city (largely in the central portion) and returned the same day by the way they had come. Seventy-one vehicles, bound to points beyond Baltimore, made stops in the city before proceeding to their ultimate destinations, and the remainder, totaling 1,157, or 21 percent of the city-entering traffic, passed through the city and emerged by several other main highways en route to destinations beyond the city.

The conditions which these examples describe are not peculiar to Baltimore and Washington. They are typical of the conditions that exist at all large cities. On all main highways approaching such cities, a very large proportion of the traffic will be found upon investigation to have originated in or to be bound to the city as its ultimate or inter mediate objective.

In general, the larger the city the larger is the proportion of the traffic on the main approach highways that is thus essentially concerned with the city.

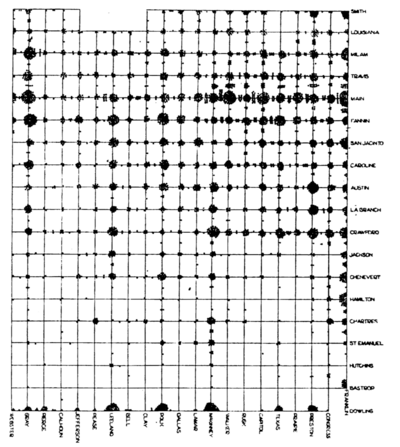

As evidence supporting this generalization, reference is made to table 14 and figure 29 which record the results of origin-destination studies made at 27 cities of various population classes, from 6 of less than 2,500 persons to one of a population between 500,000 and 1,000,000 persons. As will be observed, the studies made at 3 cities of 300,000 or more population show that upward of 90 percent of the traffic moving toward these cities on main approach highways consisted of vehicles bound to ultimate or intermediate destinations within the cities themselves. For the 4 cities of 50,000 to 300,000 population, the similar proportion of city-bound traffic was found to be above 80 percent. For the smaller cities, the corresponding proportion tends to decline, reaching 50 percent for the cities of less than 2,500 population that were studied.

| Population group | Number of cities |

Traffic bound to the city |

Traffic bound beyond the city |

| Percent | Percent | ||

| Less than 2,500 | 6 | 49.3 | 50.7 |

| 2,500 to 10,000 | 6 | 56.7 | 43.3 |

| 10,000 to 25,000 | 3 | 78.1 | 21.9 |

| 25,000 to 50,000 | 5 | 79.0 | 21.0 |

| 50,000 to 100,000 | 2 | 83.8 | 16.2 |

| 100,000 to 300,000 | 2 | 81.6 | 18.4 |

| 300,000 to 500,000 | 2 | 92.8 | 7.2 |

| 500,000 to 1,000,000 | 1 | 95.8 | 4.2 |

The proportion of adjacent main-highway traffic generated by the smaller cities, either as points of origin or points of destination, depends a great deal upon the location of the city in relation to cities of larger population. A town of 2,800 population, such as Laurel, Md., located on the main highway midway between two such large cities as Baltimore and Washington, which are separated by only 30 miles, will be neither the origin nor the destination of a large part of the heavy traffic counted on the main highway near its boundaries. In contrast, a town of approximately the same size, such as Carson City, Nev., will be found to be the source or destination of a larger part of the lighter traffic on the highway connecting it with its somewhat larger neighbor, Reno.

Similarly, among slightly larger cities, the city of Milford, Conn., a city of more than 11,000 persons, undoubtedly is responsible, as origin or destination, for a comparatively small part of the heavy traffic on the great main artery near its city limits. Located midway on U.S. 1 between the neighboring larger cities of Bridgeport and New Haven, it is directly in the path of the New York-Boston movement.

Annapolis, Md., a city of 13,000 persons, is on the other hand, either the origin or destination of a much larger part of the traffic on the spur highway that connects it with Baltimore, 30 miles away.

Among the smaller cities differences of geographic location and intercity relationship may somewhat disturb the rule. It nevertheless remains true, and among larger cities almost without exception, that the larger the city the larger will be the share of the traffic on the approach highways that has its origin or destination in the city.

Furthermore, of this city-concerned traffic, the largest single element originates in or is destined to the business center of the city. This is the area in which are located the larger stores and warehouses, both wholesale and retail, the principal banks and other financial institutions, the seat of the city government and the courts, the bigger hotels and theaters, some of the larger apartment houses, and the more influential churches. Usually it includes the principal transportation terminals, some industrial establishments, and occassionally one or more high schools and other educational institutions, the art gallery and music hall and other cultural institutions. Generally it is also the site of the original settlement of the city.

The locations of the principal rail and water terminals have been powerful factors in shaping the business center. Within the forseeable future, this area is likely to remain the objective and the source of a large part of the daily street and highway traffic. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that the interregional routes, carrying a substantial part of this traffic, should penetrate within close proximity to the central business area.

How near they should come to the center of the area, how they should pass it or pass through it, and by what courses they should approach it, are matters for particular planning consideration in each city. Since these routes should be designed to serve important arterial flows of intraurban as well as interurban character, their locations from the fringes to the center of the city should be determined in large degree by the location of internal areas in which are generated important volumes of the intraurban movement. The city streets over which the urban mileage included in the recommended interregional system has been measured, are those now marked as the transcity connections of the existing main rural highways that conform closely to the rural sections of the recommended routes. These streets generally pass through or very close to the existing central business areas of the cities.

The total milage of these streets in cities of 10,000 or more population has been classified with respect to the use of the land in the areas they traverse. This classification shows that 10.5 percent of the mileage lies within the central business areas of the cities.

In reaching the central sections, these streets pass through several other classes of development, and the percentage of mileage within areas of each class is shown in table 15. As will be seen from this table, approximately 7.5 percent of the length of these existing streets in cities of 10,000 or more population is located in areas classified as industrial, 12.2 percent in outlying business areas, 24.3 percent in areas described as mixed business and residential, 23.8 percent in residential areas, 14.7 percent in areas of scattered development, 3.4 percent in park or other municipally owned areas, and 3. 6 percent in areas of other description.

As a further indication of the character of these traversed areas, table 15 also shows those wholly or partially devoted to residence, classified as high, intermediate, and low class. The greater part of the mileage falls in what are described as areas of intermediate class.

Since it is probable that in any development of the interregional routes, the locations chosen will not follow the streets presently used in many cases, the percentages and detailed data given in table 15 can be considered as only generally indicative of the Jand uses in the areas that will be traversed, and of the nature of land-acquisition problems involved in the development.

Location internally through wedges of undeveloped land.—As previously pointed out, the improvement of highways at urban centers has in the past stimulated outward extension of city growth, and has left wedges of relatively undeveloped land between these ribbons of development along the main highways entering the city. To some extent these wedges are the result of a topography less favorable for development or of the reservation of land for various public uses. In most cases they are caused in part by the lack of satisfactory connection with the city, either by roads of direct entrance or by appropriate transverse connection with the main highways.

Whatever their cause, existing wedges of vacant land may offer the best possible locations for city-entering routes of the interregional system. Alinement and right-of-way widths appropriate for the new highways and difficult of acquisition in more developed areas, may be obtainable in these vacant spaces with relative ease and at moderately low cost. So placed, the routes may often be extended far into the city before they encounter the greater difficulties of urban location.

In choosing these locations for the arterial routes, however, it should be recognized that the undeveloped lands which lie so favorably for highway purposes also present opportunities equally favorable for other purposes of city planning. Properly preserved and developed, they can become the needed parks and playgrounds for residents of adjacent populated areas. Alternatively, they can be developed as new residential communities in the modern manner, unhampered by | Population group | Lengths traversing various areas | ||||||||||||||

| Downtown business |

Industrial | Outlying business |

Mixed business and residential |

Residential | Scattered development | Park or other municipal area |

Other | Total | |||||||

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | |||||||

1,000,000 or more . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

19.1 | 8.2 | 52.6 | 9.5 | 16.5 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 18.5 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 14.8 | 1.9 | 175.2 |

500,000 to 1,000,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

4.7 | 12.9 | 12.1 | 4.5 | 12.2 | 3.3 | 18.9 | 18.8 | 8.1 | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

3.2 | 1.1 | 10.6 | 7.5 | 113.9 |

300,000 to 500,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

14.8 | 41.8 | 40.1 | 12.4 | 34.1 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 14.6 | 29.4 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 247.2 |

100,000 to 300,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

46.7 | 37.8 | 57.8 | 17.3 | 72.4 | 30.2 | 31.6 | 44.4 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 26.7 | 13.8 | 21.3 | 25.3 | 444.4 |

50,000 to 100,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

30.8 | 20.9 | 23.8 | 13.0 | 56.2 | 5.4 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 4.3 | 15.7 | 14.1 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 10.0 | 270.3 |

25,000 to 50,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

40.8 | 15.3 | 23.6 | 11.6 | 50.1 | 17.3 | 32.9 | 60.7 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 44.8 | 12.9 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 331.8 |

10,000 to 25,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

67.0 | 23.2 | 38.4 | 29.2 | 87.0 | 18.9 | 47.0 | 95.7 | 10.8 | 13.0 | 57.3 | 27.0 | 6.5 | 19.5 | 540.5 |

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

22.39 | 159.2 | 259.4 | 97.5 | 328.5 | 89.8 | 117.9 | 280.9 | 47.1 | 48.6 | 170.1 | 94.1 | 70.9 | 75.4 | 2,123.3 |

| PERCENTAGE CLASSIFICATION | |||||||||||||||

1,000,000 or more . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10.9 | 4.7 | 30.0 | 5.4 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 10.6 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 8.4 | 1.1 | 100.0 |

500,000 to 1,000,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

4.1 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 10.7 | 2.9 | 16.6 | 16.5 | 2.7 | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2,8 | 1.0 | 9.3 | 6.6 | 100.0 |

300,000 to 500,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6.0 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 5.0 | 13.8 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 5.9 | 11.9 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 100.00 |

100,000 to 300,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10.5 | 8.5 | 13.0 | 3.9 | 16.3 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 10.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 100.0 |

50,000 to 100,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

11.4 | 7.4 | 12.5 | 4.5 | 20.8 | 2.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 5.2 | .9 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 100.0 |

25,000 to 50,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

12.3 | 4.6 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 15.1 | 5.2 | 9.9 | 18.3 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 13.5 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

10,000 to 25,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

12.4 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 16.1 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 17.7 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 10.6 | 5.9 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 100.00 |

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10.5 | 7.5 | 12.2 | 4.6 | 15.5 | 4.2 | 8.4 | 13.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 100.00 |

| 30.2 | 24.3 | 23.8 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 100.0 | |||||||||

Note.—Class 1, class2, class 3 are high-class, intermediate-class, and low-class, respectively. previous commitment to the traditional rectangular street plan. It is highly desirable, therefore, that the location and plan of the new highways in these areas shall be developed in harmonious relation with other appropriate uses of the now vacant land. Wherever possible, plans for all uses of the land should be jointly developed and acquisition for all purposes of public use should proceed simultaneously.

In any case, if the new city-entering highways are located through existing wedges of undeveloped lands, they must be connected with well developed existing suburban areas, which are usually located along the present main highways, in order to serve effectively the arterial needs of these communities. Adequate cross highways at suitable points will provide these connections. And continued around the city, from one new arterial and one existing main highway to another, these connectors become the circumferential routes which are discussed later in this section. Some of these circumferentials, especially those forming the outer belt, may appropriately belong in the interregional system, as they would serve both to distribute the city-bound interregional traffic around the city to the point nearest its destination, and also to transfer through traffic around the city from one route to another.

It will be at once apparent, however, that if the improvement of main highways in the past has resulted in the stringing out of city growth along them, the superior improvement contemplated for the new arterial routes would have the same effect in exaggerated degree. The improvement of the interregional system should be so designed as to discourage ribbon development and the unwise subdivision of large tracts of suburban land. Special preventive measures will prove helpful in this connection. One of these measures, applicable at the appropriate stages of city growth, would be to provide additional circumferential routes (as discussed in the following section), and then, as the interradial spaces widen, to add branches to the radial arteries, thus encouraging uniform development of whole areas rather than ribbon-like settlement along the radials. Another, which involves no principle of route location, is mentioned here only because of its bearing upon city development. It is the control and limitation of access to the arterial routes.

Unlimited access to the existing main highways has undoubtedly encouraged the outward extension of settlement along them. Per contra, the denial of access to the new arterial highways for a substantial outward distance beyond any desired points on these highways would probably discourage the creeping of settlement along them much beyond the selected points, and this is endorsed by the committee in principle.

Circumferential and distribution routes.—Although, as previously indicated a large part of the traffic on interregional routes approaching the larger cities will generally have its origins and destinations in the center of the city, substantial fractions will consist of traffic bound to and from other quarters of the city. Another portion—its volume depending usually upon the size of the city in relation to the sizes of other nearby cities—will consist of traffic bound past the city.

To serve this traffic bound to or from points other than the center of the city, there is need of routes which avoid the business center. Such routes should generally follow circumferential courses around the city, passing either through adjacent suburban areas or through the outer and less congested sections of the city proper.

Generally, such routes can be so located as to serve both as arteries for the conveyance of through traffic around the city between various approach highways and as distribution routes for the movement of traffic with local origins and destinations to and from the various quarters of the city. The pattern of such routes will depend upon the topography and plan of each particular city. At most relatively large cities the need will be for routes completely encircling the city.

In the larger cities more than one circumferential route may be needed. A series of them may be provided to form inner. and outer belts, some possibly within the city itself, others without. In the largest cities one such route may be required as a distributor of traffic about the business center. Often, it may be possible to serve this function by suitable locations of several of the main penetrating arteries.

Not all of these routes may be needed for the service of traffic on the interregional system, however. In some cases the needs of the interregional traffic may be largely met by a route around one side of the city, traversing only a part of the city’s circumference.

Relation to traffic-generating foci and terminals.—Railway terminals, both passenger and freight, wharves and docks and airports, generate large volumes of street and highway traffic. Much of it is of express character, and significant fractions are associated with the essential interchanges between the several modes of transportation. Both passengers and freight are transferred between railroads and ships, and passengers between railways and air lines. The future development of commercial air cargo and express freight transportation should not be underestimated in considering this shuttle movement between transportation media.

Railway terminals and docks are commonly located at mid and low city points. The principal airports probably must remain at or beyond the fringe of the city.

The location of the interregional routes at cities—both the city-penetrating main routes and the circumferential.or distribution routes—should be so placed as to give convenient express service to these various major traffic-generating foci within and in the environs of the city, and also to the business center of the city, the wholesale produce market, main industrial areas, principal residential sections new housing developments, and the city parks, stadium, baseball park, and other sports areas.

Location of the routes should be determined in relation to such foci in the positions where they are planned or are likely to be in the future and not where they are at present, if change is reasonably to be expected. Thus the closest possible cooperation is needed between highway, housing, and city planning authorities, railroad, motorbus, and truck interests, air transport and airport officials, and any other agencies, groups and interests that may be in a position to exert a determining influence upon the future pattern and development of the city.

Moreover, the highways themselves should have their own adequate terminal facilities—facilities hitherto sadly lacking. There are two general classes of highway terminals—those designed for the daily or overnight accommodation of private vehicles (principally passenger cars) with destinations at the center of the city, and those serving the organized transportation business of bus and truck lines.

The former (generally termed parking garages) constitute a more or less separate problem which is more fully discussed later in this report.

The latter are interrelated with the terminals of other transportation media, such as those of rail, water, and air.

Union bus terminals are desirable. They should be located at points convenient for express highways to provide for adequate interchange of passengers with railroads, wharves, and airports, and for collection and conveyance of passengers from and to the principal city areas in which their trip origins and destinations lie.

Truck terminals also should be conveniently accessible by the express highways, and these should be located at points appropriately chosen to facilitate the transfer of freight to and from railroad and water transportation especially. Again union terminals are desirable, not only for convenience of transfer to other modes of transportation but also for promotion of the possibilities of return truckloads.

Different classes of freight may require the establishment of more than one such terminal. The terminal for industrial freight, for example, should be located in or convenient to the area of principal industrial concentration. Another terminal may be required in or near the commercial center; and another at a point convenient for the transfer and delivery of agricultural produce. The latter would serve as both terminal and produce market and should be designed accordingly in both location and space accommodation.

In all cases, the essential service requirements of these highway terminals, both passenger and freight, will fix them within certain more or less prescribed areas, and this prescription: will have an important bearing upon the location of the interregional and other express highway routes.

Relation to other transportation media.—At cities, especially, it is important that the location of interregional routes be so chosen as to permit and encourage a desirable coordination of highway transportation with rail, water, and air transportation. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that opportunities for joint use of new structures by the interregional routes and mainline railroads should not be neglected wherever they may appear. The feasibility of combination rail-and-highway tunnels to eliminate the costs of snow removal or protection and to reduce grades over some western mountain passes, should be carefully investigated. It will be desirable to study at numerous points the possibilities of providing in a single structure, whether bridge or tunnel, for the crossing of rivers and other bodies of water by interregional routes and main railway lines.

However, it is at the cities—terminals alike for the interregional routes and all other transportation media—that the closest attention should be paid to the possibilities of common location, and also to such location of the highways as will best and most conveniently serve to promote their use in proper coordination with other transportation means.

There are possibilities of the development of common city approaches of rail and highway, either in parallel surface or depressed location, or with the highway above a railway tunnel. These possibilities should be carefully explored. In many cities the surface location of railways remains as one of the more acute problems facing the city planner. Instead of attacking this problem piecemeal by elimination of grade crossings one or two at a time, a practice which tends merely to ameliorate a generally unsatisfactory condition, it would be far better if it were dealt with in accordance with a plan for the complete and permanent insulation of the railway. Since the interregional routes and other express highways require, in some degree, a similar insulation, a plan for the common location of the two facilities might offer not only the advantage of a minimum obstruction of cross streets but also a substantial possibility of reducing the total costs of achieving the two purposes, particularly the right-of-way element of such costs. A striking development of this character in the city of New York is illustrated in plate I.

Relation to contemplated developments requiring large tracts of land.—Wherever it is possible to do so, the location of interregional routes in cities should be considered simultaneously with the projected location of new housing developments, city centers, parks, greenbelts, and other contemplated major changes in the existing city pattern that call for the acquisition of land in large tracts. This is necessary for the avoidance of conflicts in plans; it is necessary from the standpoint of adequate transport accommodation; and it is highly desirable from the viewpoint of common land acquisition and financing. The location of express routes within or adjacent to such areas may be one of the most fruitful means of avoiding street intersections, but should only be applied subject to a proper regard for the character, uses, and needs of the several areal developments.

Minimization of street intersections.—In the operation of motor vehicles we are conscious today as never before of the rubber-and-gasoline costs of stopping and starting.

Investigations by the Iowa State College on the wear of tires show, for example, that at the wartime maximum speed of 35 miles an hour, a single stop and start normally wears away about as much rubber as a mile of travel.

Other investigations by the Iowa college have determined that at the same wartime speed, a single stop and start by an average passenger car consumes as much gasoline as 0.15 mile of driving on a straight highway of average gradient.

Under any circumstances stopping-and-starting costs constitute tangible amounts worth saving.

The frequency of street intersections is the cause of excessive stops and starts in cities. Every intersection also introduces substantial elements of delay and congestion.

If the permissible speed of moving traffic is 35 miles per hour, a halt of only half a minute at a traffic light consumes time in which each halted vehicle, but for the stop, would have advanced nearly 4 average city blocks. On a street carrying a daily traffic of 10,000 vehicles, if this traffic were equally distributed throughout the 24-hour day, one such traffic light operated on a half-minute interval would prevent 739 vehicle-miles of movement in a single day.

These calculations ignore the time lost in starting and stopping. If this also were subtracted, the total daily loss of vehicle-mileage might easily be doubled, and 10 lights under these conditions might rob the entire traffic stream of nearly a mile and a half of movement daily. The Public Roads Administration’s studies of the traffic-discharge capacity of highways have reached the conclusion that a one-way, two-lane roadway with no intersections will discharge without unreasonable congestion an hourly traffic of 3,000 vehicles moving at an average speed of 35 miles per hour. With equal congestion but with three traffic lights per mile, each set on a half-minute interval, the hourly discharge is reduced to at best 1,500 vehicles an hour. One or two more traffic lanes would have to be provided to restore the highway to its intersection-free capacity.

Photo by Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc.

Reduction of the number of intersections presents problems in the design of arterial routes and the control of traffic flow more difficult of solution than similar problems encountered on rural highways. For instance, the ideal arterial street would have no intersections, yet it is obvious that all cross streets cannot be closed in order to attain this ideal.

One solution is to eliminate intersections by means of grade separations. Grade separations eliminate the hazards, delays, and costs entailed by encounter with cross-traffic streams. They involve expensive construction, however. A judicious choice of location to minimize the number of intersections is one means of avoiding this expense.

Wherever it is possible to do so with satisfactory accommodation of the local arterial traffic, arterial routes should enter the city at points from which it is possible to proceed as near as desirable to the city center and thence to connection with the continuing rural routes at the opposite side of the city, by locations parallel to one or the other direction of the normal rectangular street plan. Such locations will usually encounter a minimum number of street intersections in traversing the city and are generally to be preferred for this reason. They are also preferable to diagonal or curving locations because of the greater simplicity of the intersections.

Locations adjacent to the usually winding or curving bank of a river or the curved or diagonal line of a railroad should be considered as exceptions to the rule stated above. Such locations usually offer the advantage of protected or infrequent access from one side, and this may offset the disadvantage of greater length within the city and consequent number of streets passed on the other side.

Location in proximity to a railroad is generally considered somewhat objectionable. It need not be, however, if by electrification, the use of Diesel power, appropriate screening and landscaping, or other means, smoke, noise, and unsightliness are abated.

The valley of a small stream penetrating a city may offer excellent opportunity for the location of an intersection-free artery. In many cases such small valleys exist in a wholly undeveloped state. In others they are the locations of a very low order of development—neighborhoods of cheap, run-down houses and shacks, abject poverty, squalor, and filth. ere these conditions exist, steep declines into the valley have generally made the site unfavorable for the development of high-class improvements.

Nor is it entirely accidental that these small stream valleys often lead in directions favorable for arterial routes penetrating from the outskirts of the city to points near its heart. In many cases the original settlement of the city grew up about the junction of these small streams with a larger stream, and the place of the original settlement is the center of the present city.

Often a small valley of this kind interrupts completely or more or less effectively many of the transverse streets. Intercourse within the city has already adjusted itself to crossing at relatively few principal points where bridges have been provided. Under these conditions the valley may provide the most fortunate of opportunities for the location of city-entering arterial routes. Its conversion to that use may yield the benefits not only of quick and free traffic flow, but also of eradication of a long-standing eyesore and blight upon the city’s attractiveness and health. Even at the expense of some indirection in the location of the route, it may be greatly advantageous to convert undeveloped areas to such use.

Other locations favorable for the reduction or simplification of intersections on the arterial routes may be found within or along the boundaries of parks and other large tracts of city or institutional property that interrupt the regular rectangular street plan. An examination of the city for opportunities of this sort may be rewarded by the discovery that it is possible to project reasonably direct routes from one such area to another with substantial advantage in the reduction of intersection problems.

After an interregional route has been carefully located so as to minimize the number of cross routes, a considerable number will still exist. The grade of all that cannot be avoided should then be separated.

And finally, all sections of the interregional system in cities—those serving as circumferential distributors as well as the city-penetrating routes—should be established as arterial highways of limited access. The principle of limited access is outlined in a later section of this report.

Relation to urban planning.—It should be borne in mind that the interregional routes, from the standpoint of the city, will provide only a partial facility for movement of the city’s traffic. That part whether great or small, should be determined in location and designed in character to be a consistent and useful part of the entire urban transportation plan. As previously suggested, the entire plan should be conceived in relation to a desirable pattern of future city development.

The present flow of traffic within the city is affected by the existing pattern of land use, the existing location of railroad and other transportation terminals, the existing concentrations of business, industrial, and cultural establishments, and the existing location of residential areas of various classes. It is probable that many of these existing land uses will be materially changed within the life period of any substantial new traffic facilities now provided. Such material changes must be expected even if there is no planned direction of the course they should take, and the location and character of the new routes provided should anticipate them as fully as possible.

By careful and complete functional studies of the city organism, it may be possible to devise a rational plan of future land use that will assign more or less specific areas to each of the principal classes of use—residental, cultural, business, industrial, etc. Having planned such rational distributions of land use, it may be possible to obtain the public consent necessary to the establishment of legal controls, land authorities, and other devices and machinery that will assure an actual development over a period of years in conformity with the plan. In such case, the planning of city streets, the interregional routes and other express ways, and all other urban facilities would take the forms and locations necessary to serve the intended land uses, and these facilities would be provided in essential time relationship to the development of the entire plan, and in a manner to bring about its undistorted realization. The interregional routes, however they are located, will tend to be a powerful influence in shaping the city. For this reason they should be located so as to promote a desirable development or at least to support a natural development rather than to retard or to distort the evolution of the city. In favorable locations, the new facilities, which as a matter of course should be designed for long life, will become more and more useful as time passes; improperly located, they will become more and more of an encumbrance to the city’s functions and an all too durable reminder of planning that was bad.

It is very important, therefore, that the interregional routes within cities and their immediate environs shall be made part of the planned development of other city streets and the probable or planned development of the cities themselves. It is well to remember in this connection that observations of the existing traffic flow may not be an infallible guide to the best locations.

In many cities there are city planning commissions that have already given thought to desirable changes in the present city structure. Some of these bodies have reached quite definite decisions regarding many of the elements that will affect the location of interregional highways in and near the city. Usually the decisions of the planning commission have grown out of studies of the city as it is, and as the commission desires it to be. And these studies will usually afford the principal data and bases for agreement upon the general locations of the interregional routes.

It is especially desirable that the agreement have the full concurrence of housing and airport authorities and other public agencies that may be concerned with the acquisition of large tracts of land in and near the city. This is desirable in order that the routes may be properly located for adequate service of the developments planned and that the lands needed for the highways and the new facilities and developments they are designed to serve may be mutually agreed upon and simultaneously and cooperatively acquired.

Illustrations of Principles of Route Selection

To illustrate many of the principles of route selection in cities, as well as the range of conditions that may be encountered at cities of various sizes, figure 31 gives schematic lay-outs of several possible conditions of main penetrating and circumferential or distributor routes.

At the small city.—The simplest case is that of the small city, illustrated by diagram A. In this case the interregional highway passes on a direct course wholly without the city. The former main highway which now serves as a city service road, diverges from the interregional route at some distance on opposite sides of the city. Thus it provides a connection between the interregional and the other main highway that passes through the small city. The service road may or may not be considered as part of the interregional system, depending upon the size of the city, its distance from the interregional route, and the relative volume of the traffic the service road and the other main highway contribute to the interregional system. In this case, however, no circumferential or distributing routes are needed.

In the city of medium size.—Diagram B illustrates the case of a city of medium size. In this case a single route of the interregional system approaches the city from the north and south and necessarily passes through the city closely adjacent to the business section to pick up and deliver the substantial volume of traffic there originated or destined.

For the accommodation of the considerable volume of through traffic on the interregional route, a circumferential route, considered as part of the interregional system, diverges to the right at a convenient point south of the city and passes along the eastern boundary to rejoin the main route at a point north of the city. The distance around the city by this route is little if any longer than the distance through the city by the main route. The circumferential route serves also to pick up and deliver traffic at several accesses provided in the city’s eastern quarters.

Another main highway, not included in the interregional system, intersects the interregional route at the center of the city. For transfer of through traffic between this route and the interregional route, a circumferential route is provided around the west side of the city, but because of its relative unimportance in the service of interregional traffic, this route is not considered as part of the interregional system.

In the large city.—Diagram C illustrates the complex pattern of main and circumferential interregional routes and other local belt lines that may be required for the adequate service of both interregional and local traffic at a large city. In this case, three interregional routes intersect at the city and all must pass within convenient reach of the large central business section.

One follows along the bank of the river as it approaches the city and continues in this location through the city.

Another approaches from the northeast and enters the city through a wedge of undeveloped land, then passes on a north–south course along the border of a new housing development, skirts the eastern fringe of the business section, crosses the river, and finally resumes its southwesterly course as it emerges from the city.

The third crosses the city from east to west, skirting the northern edge of the business section.

In addition, several other principal highways center in the city.

In this case, the three interregional routes combine to perform the function of traffic distribution around the business section.

At convenient points to the north, east, south, and west of the city, interregional circumferential routes intersect the main penetrating routes and serve to transfer through traffic from one to another, an to distribute the interregional traffic to the several quarters of the city. The locations of these routes are such that in no case is the distance around the city materially different from the through distance.

To the north of the city there is considerable scattered suburban development, and the northern leg of the interregional circumferential route crosses east and west above all this development.

An additional east–west distributor closer to the city is located as an inner circumferential route approximately along the northern city limits. It connects with the eastern interregional circumferential and with the riverside interregional route. Since it performs mainly a local distributing service, it is not considered as part of the interregional system. Within the area circumscribed by the interregional circumferential routes, access is provided to the main interregional routes and the circumferential routes at several suburban communities and at certain streets which extend uninterruptedly across the city, and which for that reason are well adapted as internal collectors and distributors of traffic.

The diagrams of figure 31 represent purely imaginary cases. An effort has been made, however, to include in them some of the situations that may be commonly encountered. Study of these diagrams will suggest most of the essential locational relations of the main interregional routes and circumferential and distributing routes, and the difference between circumferential routes that should properly be considered as parts of the interregional system and those that may not be so considered because of their primarily local function.